Emma of Normandy

Emma (c. 985–March 6, 1052 in Winchester, Hampshire), called Ælfgifu, was daughter of Richard the Fearless, Duke of Normandy, by his second wife Gunnora. She was Queen consort of the Kingdom of England twice, by successive marriages: initially as the second wife to Etherlred (or Æl of England (1002-1016); and then to Canute the Great of Denmark (1017-1035). Two of her sons, one by each husband, and two stepsons, also by each husband, became kings of England, as did her great-nephew, William the Conqueror, Duke of Normandy who used his kinship with Emma as the basis of his claim to the English throne. Her first marriage was by arrangement between her brother, Richard II of Normandy and the English king, 20 years her senior, to create a cross-channel alliance against the Viking raiders from the North, with whom Emma was also related. Canute, 10 years her junior, as king by conquest not by right, used his marriage with the Queen to legitimize his rule.

An innovation in the Queen's coronation rite (her second) made her a partner in his rule, which represents a trend towards Queens playing a more significant role, at least symbolically, as peacemakers and unifiers of the realm. She is considered to be the first Queen who was called Queen Mother when her sons ruled as monarch. Her first marriage resulted in her acquiring considerable land and wealth in her own right. She used her position to become one of the most powerful women in Europe, possibly acting as regent during Canute's absences and after his death in 1035, when she controlled the royal treasury. With Canute, as well as in her own right, she was a generous benefactor of the church. Edward the Confessor, her son, became a Saint. She was consulted on matters of state and on church appointments. Edward relieved her of most of her possessions in 1043, claiming that they belonged to the king and banished her to Winchester. She was re-instated at court the following year. Arguably the most powerful women in English history until Elizabeth I, she helped to shape developments that paved the way for women, centuries later, to rule in their own right. Her partnership with Canute saw several decades of peace. While some may blame her for the Norman Conquest, her great-nephew's rule also brought England into the context of a larger entity, that of Europe. The subsequent mixture of Anglo-Saxon and French cultures became, over the years, a foundation for integrating England into the European cultural life.

Life

Emma was the son of the Duke of Normandy, Richard the I and the sister of his heir, Richard II. Richard negotiated her marriage with the English king, Ethelred. She would not have learned to read or write although she may have had some instruction in Latin. She would have spoken a form of Old Scandinavian. Her training would have consisted of preparation for a royal marriage ti further the interests of the Dukedom and its ruling family. Her mother exercised considerable power at court, which may have given her ideas about how she would act as a king's wife. Her mother was also a "major player at court during several years of her son's reign."[1]

First Marriage

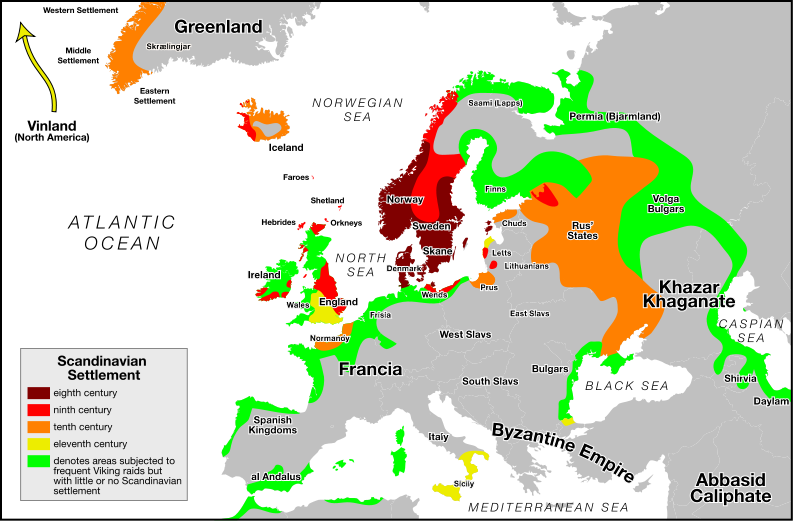

Ethelred's marriage to Emma was an English strategy to avert the aggression of dangerous Normandy by way of an alliance. Normandy was under feudal obligation to the kings of France. However, England was the Norman dukes' main target, after inter-baronial feuds and rampaging pillages through Brittany had run their course and English kings could not afford to underestimate the Norman threat. Marriage between Ethelred and Emma promised an alliance with Normandy and protection against the Vikings who constantly raided from the North. A year before Emma's marriage, a Danish fleet had pillaged the Sussex coast. O'Brien writes that Emma would have been prepared from childhood for this type of marriage, in which her role would be that of a "peace-weaver," the "creator of a fragile fabric of friendship between hostile marriage."[2] Although Ethelred was already married and Emma was to be his second wife, Richard II would have specified in the terms of the marriage that his sister be crowned Queen and given gifts of land. She received estates in Winchester (which was a traditional bridal gift for English Queens), Nottinghamshire and Exeter as her "personal property."[3]. Her marriage in 1002 was followed by a Coronation, which, says O'Brien, symbolized not only her union with the King "but also with his country." A later account describes her as wearing "gowns of finely woven linen" and an outer robe "adorned with embroidery into which precious stones were stone."[4] Marriage and coronation were likely to have been "staged with a great deal of splendour" since no English king had married a foreign bride for eighty years.[5] On the one hand, recognition of her status as Queen did not confer any "great authority" but on the other hand it "elevated Emma way above her husband's subjects and offered healthy scope for developing a role of enormous power."[6] Emma's name was Anglicized as Ælgifu.[7] Ethelred had six children by his first wife, who does not appear to have been crowned as Queen, unlike Emma. Two wives was not uncommon during this period when both pagan and Christian marriage practices co-existed. Thus, while the second forbade bigamy, the first sanctioned this. O'Brien speculates that Etherlred's first wife may have died, or that he chose to ignore this marriage because Emma was a better match; "It was not uncommon for a man, particularly a person of rank, to ignore his marriage vows if a better alliance with another family came his way - Emma's own family history was, after all, littered with such untidy arrangements."[8] Her family would have insisted that there be no doubt about the legality of the marriage.

Having male sons was considered to be one of the most important roles a Queen had to fulfill, important both for her royal husband who needed heirs and for her own family, who wanted the alliance to continue after Ethelred's death. Dutifully, Emma gave birth to two sons, Edward and Alfred and a daughter, Godgifu (or Goda). Ethelred already had male heirs but the tie with Normandy would be strengthened by children and part of the agreement with Richard may have been that if Emma had a male son, he would become heir-apparent.[9][10] More male children, too, could help to secure a dynasty's future since princes died or were killed in battle. On the other hand, royal sons also vied for succession; the rule of primogeniture was not firmly established and often the son who proved to be the strongest succeeded. A Queen's position could be risky if she was unable to produce male children; on the other hand, "a new Queen became a more assured member of the family when she produced its children."[11] Whether or not such an agreement existed, Emma's estates appears to have been augmented following each birth. Also, she made gifts of land to each of her children, which demonstrates "that she clearly had powers in her own right."[12] Later, she became renowned for patronizing the Church and she may have founded some Abbeys and monasteries during this period. Her legacy to Edward included the founding of Eynsham Abbey. The account of her life commissioned by Emma herself, the Encomium Emmae omits this period of her life focusing instead on her later marriage with Canute. While this account stresses Emma's role as a sharer in royal power, she does not appear to have exercised the same degree of power while married to Ethelred. On the other hand, she would at the very least have been involved in discussion related to the marriage of her step-children, always a strategic issue. Later, she made strategic decisions regarding her daughters' marriages. Her first daughter married the Count of Vexin, to whom she bore a son. He became the earl of Hereford. When her first husband died, she married the powerful count of Boulogne.

The Danish Invasion

Danish armies constantly invaded over the next decade, which could only be halted by payment of the Danegeld. Ethelred had little military success against these invasions. In 1002, the year he married Emma, Ethelred took vengeance on the Danes by killing anyone of Danish blood found in England. Known as the St. Brice's day massacred (because it took place on Image November 13, St Brice's Day) for which in turn the Dane's were determined to take revenge. His eldest son Æthelstan, died in 1014, after which his second son, Edmund challenged him for the throne. The resulting instability gave the Dane's the opportunity they needed. In 1013, Sweyn I of Denmark (known as Sweyn Forkbeard) accompanied by his son, Canute, invaded and smashed Ethelred's army. Emma's sons by Ethelred - Edward the Confessor and Alfred Atheling - went to Normandy for safety, where they were to remain. Ethelred also took refuge overseas, returning after Sweyn's death a few weeks later. The Danes declared Canute King of England as well as of Denmark but in the initial confrontation between Ethelred and Canute, he was forced into retreat. Returning to Denmark, he recruited reinforcements and invaded again in 1015. It was Edmund, who earned his title as a result of leading the defense of the realm, who led the resistance against Canute's onslaught. Ethelred, who was now ill, died April 23, 1016. Edmund succeeded him as Edmund II. He was, however, losing the war. The final battle took place October 18, 1016, after which Edmund and Canute chose to enter a peace agreement by which Edmund and Canute would each rule half of England. Edmund, however, only lived until November 30th. After his death, Canute became king of all England. As her husband and step-sons died and the Danish king assumed power, Emma was faced with a choice; to remain in England or to flee to Normandy. She chose the former. Had she returned to Normandy, she would have had very little status there and would have "been entirely dependent on her family." In England, she possessed land and personal wealth.[13] This proved to be the right decision. Having conquered England, Canute needed to legitimize his rule in the eyes of the English or face constant revolt and opposition. At this period, kingship was understood in terms of royal birth - you were born to be King, or at least into the ruling family. Canute was concerned to legitimize his rule; one method was by marrying the Queen. "As the widow of an English king, she was already an English Queen; her consecration could now serve as a symbol of continuity if not of unity."[14]

Danish armies constantly invaded over the next decade, which could only be halted by payment of the Danegeld. Ethelred had little military success against these invasions. In 1002, the year he married Emma, Ethelred took vengeance on the Danes by killing anyone of Danish blood found in England. Known as the St. Brice's day massacred (because it took place on Image November 13, St Brice's Day) for which in turn the Dane's were determined to take revenge. His eldest son Æthelstan, died in 1014, after which his second son, Edmund challenged him for the throne. The resulting instability gave the Dane's the opportunity they needed. In 1013, Sweyn I of Denmark (known as Sweyn Forkbeard) accompanied by his son, Canute, invaded and smashed Ethelred's army. Emma's sons by Ethelred - Edward the Confessor and Alfred Atheling - went to Normandy for safety, where they were to remain. Ethelred also took refuge overseas, returning after Sweyn's death a few weeks later. The Danes declared Canute King of England as well as of Denmark but in the initial confrontation between Ethelred and Canute, he was forced into retreat. Returning to Denmark, he recruited reinforcements and invaded again in 1015. It was Edmund, who earned his title as a result of leading the defense of the realm, who led the resistance against Canute's onslaught. Ethelred, who was now ill, died April 23, 1016. Edmund succeeded him as Edmund II. He was, however, losing the war. The final battle took place October 18, 1016, after which Edmund and Canute chose to enter a peace agreement by which Edmund and Canute would each rule half of England. Edmund, however, only lived until November 30th. After his death, Canute became king of all England. As her husband and step-sons died and the Danish king assumed power, Emma was faced with a choice; to remain in England or to flee to Normandy. She chose the former. Had she returned to Normandy, she would have had very little status there and would have "been entirely dependent on her family." In England, she possessed land and personal wealth.[13] This proved to be the right decision. Having conquered England, Canute needed to legitimize his rule in the eyes of the English or face constant revolt and opposition. At this period, kingship was understood in terms of royal birth - you were born to be King, or at least into the ruling family. Canute was concerned to legitimize his rule; one method was by marrying the Queen. "As the widow of an English king, she was already an English Queen; her consecration could now serve as a symbol of continuity if not of unity."[14]

Change to the Coronation Rite

Although she was ten years his senior, there appears to have been sound reasons for this decision, although it may also have followed a custom whereby conquering Vikings married, as a prize, the widow of their slain enemy. There is evidence, though, that considerable thought went into designing the ritual by which Canute would be crowned King and Emma would be crowned Queen, her second coronation. this took place in 1017. This thinking must have involved the Archbishop of Canterbury, who alone had the right to crown the king and Queen. The ritual emphasized throughout that the new King, and his new Queen, were "English." A change in the words of the rite refer to Emma, as Queen, as partner in her husband's rule, as consors imperii. The rite made it quite explicit that Emma was to be "a partner in royal power." Stafford says that "1017 produced the theoretical apotheosis of English Queenship, ironically achieved in defeat and conquest." Canute chose to stress, via the coronation rite, that the rod with which he was invested was a "rod of justice, "not a rod of power and domination." Emma's rite also stressed that she was to be a "peace-weaver."[15] There was, says Stafford, "no hint of subordination".[16]

The Cult of Mary

It may be significant that at Winchester, the "dower borough of English Queens" the cult of Mary as Queen of Heaven was gaining popularity at this time. This appears to have impacted visual representation of Emma as Queen.

Artistic representation of Canute and Emma (representations of Emma are the oldest of any English Queen to have survived) also stress their equality. In one drawing:

<blockquoate>

Emma bursts from the obscurity of earlier Queens in an image with equates her in stature with Cnut, deliberately parallels her with Mary above her, and places her, along with Mary, on the superior right-hand side of Christ ... the cult of Mary Queen of Heaven went hand in hand with the growing prominence of the English Queens of earth.[17]

Marriage with Canute

Canute was already married although appears to have separated from his first wife, Ælfgifu of Northampton[18], in order to marry Emma. Emma is said to have personally negotiated terms which included the pledge any son she bore him should be his heir. This, of course, fulfilled her own obligations to her Norman family.[19]

Not only in art but also in reality, Canute and his Queen appear to have shared the responsibilities of leadership. On the one hand, there is little doubt that Emma was a junior partner. On the other hand, records show that they jointly endowed many churches and Abbeys; Emma is said to have often stood at Canute's side, helping to translate English - which she had learned - and advising on appointments. Churches patronized included the Cathedral at Canterbury, the Old Minister at Winchester and Evesham Abbey. They also sent gifts overseas. [20] Emma was instrumental in promoting the cult of Ælfheah, the murdered Archbishop of Canterbury and had personal possession of some sacred relics, including those of St. Oeun, which she donated to Canterbury and of St. Valentine, which she donated to Winchester's New Minster. Some relics may have been stolen from her household, possible including the head of St. Oeun, which she had kept, towards the end of her life. However, O'Brien says that the head was later found among her treasury and donated to Westminster Abbey.[21] Beautifully bound books were also part of her treasure.

Stafford says that she was consulted on "a range of transactions, from land purchases, to the confirmation of episcopal appointments and the making of wills."[22] Canute, says O'Brien, relied "heavily on her judgment and guidance."[23]. Stafford thinks that when Canute was absent from England, visiting Denmark, even though there is no official record of this, Emma may have acted as regent possibly not as sole regent but with specific duties alongside other senior advisers.[24] Her role is attested to by inclusion in witness lists, where she often appears between the two archbishops (Canterbury and York), which is marks "her out among early English Queens." In the Chronicles of the times, Emma emerges as a "commanding figure in her own right."[25]

Her son by Canute, Hartacanute was born in 1018. Their daughter, Gunhild, later the wife of the [[Holy Roman Empire}Holy Roman Emperor]], Henry III, was born in 1020.

Queen Mother and Regent

After Canute's death in 1035, Harthacanute was proclaimed king. He was only 16 and while contemporary accounts are unclear whether Emma was officially recognized as regent, they are clear that she acted on his behalf between 1035 and 1037. At least one account calls her "regent" although with specific reference to the earldom of Essex.[26] In 1036, Emma's children, Edward and Alfred returned to England to see their mother. Harthacanute, however, was challenged as heir by Harold Harefoot, Canute's son by Ællfgifu of Northampton, who put himself forward as Harold I, supported by many of the English nobility. In the subsequent conflict, the younger Alfred was captured, blinded, and shortly after died from his wounds. The elder, Edward, escaped to Normandy. Emma herself had little choice but to flee, leaving for the court of the Count of Flanders. She had relatives there. She may have preferred to live on their hospitality than on her family's in Normandy, who may have seen her as having failed to secure England for the Norman dynasty. It was at this court that the Encomium Emmae, the Chronicle of her own life commissioned by Emma, was written. As well as emphasizing her role as benefactress and as a sharer in Canute's rule, the Enconium defended her sons' claim on the English throne. Throughout the narrative, her status as Queen is also emphasized although she is also described as "The Lady." After 1840, she is also referred to in some accounts as "Queen Mother" perhaps qualifying as the first English Queen to be awarded this title. In the Enconium her exile in Flanders is described as having lived in suitable royal dignity but "not at the expense of the poor." Her niece's stepson, Baldwin, was the regent.[27]

With Harold's death in 1040, Harthacanute, who had lost his Norwegian and Swedish lands but who had he had made his Danish realm secure, became King of England. Again, Stafford surmises that from 1840 until 1842, Emma may have enjoyed regency-like authority. This time, her son was over 18 but she may have argued that since he was unmarried, her own consecration as Queen remained valid, so she was entitled to continue to share in power.[28] Edward was officially made welcome in England the next year. Harthacanute told the Norman court that Edward should be made king if he himself had no sons. He died from a fit, unmarried and childless, in 1042 (at least he had no acknowledged children) and Edward was crowned King of England on the death of Harthacanute, who, like Harold I, met his end in the throes of a fit. Emma also returned to England but a rift had developed between her and Edward, who sent her into exile in 1043. What is clear is that when Canute died, Emma had control of the royal treasury, and regent or not continued to guard this through Harthacanute's reign. Edward is said to have complained that Emma had no love for him and had neglected him as a child but it is more likely that he thought his mother possessed property that he, as King, ought to control.[29] He relieved her of her property, leaving just sufficient for her upkeep. She was, says Stafford, surmising that Edward may have wanted to distance himself from the influence of a woman who had been Queen for 40 years, "cut down to the minimum rights of widowhood".[30]

Exiled in Winchester, rumor circulated that she was having an amorous relationship with the Bishop. According to later accounts, she was challenged to prove her innocence by undergoing ordeal by fire, which she did. She was found to be innocent.[31]

She tended her husband's grave at Winchester, "one of the most accepted and acceptable activities of widowhood."[32] She would be buried alongside him in the Old Minster, the first Queen to be laid to rest there and the first since Alfred the Great's wife to be buried next to her husband. Stafford thinks that this innovation may have been intended to stress the Christian view of marriage as indissoluble, since "in tenth-century royal households, husbands and wives were not often united in death."[33] She was re-instated at court in 1044 but from then until her death, March 6 1052 "little or no evidence has survived of her activity."[34] Her own Chronicle end with her and her sons ruling as a type of "Trinity," "united by maternal and fraternal love," the "Queen Mother and sons together."[35] When Edward, Emma's great-nephew used his kinship with the former Queen Mother to claim the English throne. For better or for worse, Emma was "the conduit through which Norman blood and ultimately Norman dukes entered England and its story."[36]

Encomium Emmae Reginae or Gesta Cnutonis Regis

This is an 11th century Latin encomium in honor of Queen Emma of Normandy. It was written in 1041 or 1042 at her own request. The single manuscript surviving from that time is lavishly illustrated and believed to be the copy sent to Queen Emma or a close reproduction of that copy. One leaf has been lost from the manuscript in modern times but its text survives in late paper copies.

The Encomium is divided into three books. The first deals with Sweyn Forkbeard and his conquest of England. The second deals with his son, Canute the Great, his reconquest of England, marriage to Emma and career as king. The third deals with events after Canute's death; Emma's troubles during the reign of Harold Harefoot and the ascension of her sons, Harthacanute and Edward the Confessor]] to the throne.

The work strives to show her and Canute in as favorable a light as possible. For example, it completely omits mention of Emma's first marriage, to Ethelred. It is especially significant for shedding light on developing notions of the role of the Queen as a sharer in royal power, Throughout, Emma's status as Queen is writ large in the text. Even in exile, she remains a Queen.

The Encomium is an important primary source for early 11th century English and Scandinavian history.

Legacy

Emma lived during turbulent times when the kingdoms of Europe were led by "warrior kings" who openly competed for each others' territory.[37] Daughters of ruling houses were expected to assist in forming alliances. Emma spent her life attempting to cement relations between

as a reconciler and peace-maker and as representing the Queen of Heaven on earth. Prayer at her consecration stressed her role as peace-maker.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Campbell, Alistar (editor and translator) and Simon Keynes (supplementary introduction) (1998). Encomium Emmae Reginae. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-62655-2

http://www.behindthename.com/name/emma

Bibliography

- Pauline Stafford. [Queen Emma and Queen Edith: Queenship and Women's Power in Eleventh-century England] 2001 Blackwell's

- Isabella Strachan. [Emma: The Twice-crowned Queen of England in the Viking Age] 2005 Peter Owen

- Harriet O'Brien. [Queen Emma and the Vikings] 2005 Bloomsbury U.S.A.

- Helen Hollick. The Hollow Crown. (August 2004) William Heinemann, Random House. ISBN 0-434-00491-X; Arrow paperback ISBN 0-09-927234-2. This is a historical novel about Queen Emma of Normandy, explaining why she was so indifferent to the children of her first marriage.

- Noah Gordon. [The Physician] 1986 Macmillan ISBN 067147748X . Novel set in the early 11th century.

References

- ↑ O'Brien, page 36.

- ↑ O'Brien, page 12.

- ↑ O"Brien, page 36

- ↑ O'Brien, page 36.

- ↑ O'Brien, page 34

- ↑ O'Brien, page 36-37.

- ↑ Stafford, page 3

- ↑ O'Brien, page 33.

- ↑ Stafford, page 221.

- ↑ O'Brien, page 34.

- ↑ Stafford, page 221.

- ↑ O'Brien, page 66.

- ↑ O'Brien, page 103.

- ↑ Stafford, page 178

- ↑ Stafford, page 177.

- ↑ Stafford, page 34.

- ↑ Stafford, page 178.

- ↑ who happened to have the same name as Emma's Anglicized version.

- ↑ O"Brien, page 103.

- ↑ Bakken, William. 1998. An Assessment of the Christianity of Cnut the Great. Minesota State University Mankato. Retrieved August 12, 2008. See "Table 1: Cnut and Emma's Patronage of English Churches".

- ↑ O'Brien, pages 215.

- ↑ Stafford, page 222.

- ↑ O'Brien, page 115

- ↑ Stafford, page 188. Stafford comments that those who apparently acted as regents are not always described as such in contemporary accounts but thinks it likely that Emma was part of an ad hoc regency council.

- ↑ O'Brien, page 21.

- ↑ Stafford, page 189.

- ↑ Stafford, page 251.

- ↑ Stafford, page 190.

- ↑ Stafford, page 115.

- ↑ Stafford, page 249.

- ↑ Stafford, page 20-21. These accusations may have been made as early as 1043 or as late as 1051. See also Ford, David Nash. 2001. Royal Ordeal by Fire. Berkshire History. Retrieved August 13, 2008.

- ↑ Stafford, page 253.

- ↑ Stafford, page 95.

- ↑ Stafford, page 4.

- ↑ Stafford, pages 37 and 191.

- ↑ Stafford, page 14.

- ↑ O'Brien, page 13.

| Preceded by: ? |

Queen mother 1035 - 1052 |

Succeeded by: Edith of Wessex |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.