Danegeld

The Danegeld ("Dane gold") was an English tribute raised to pay off Viking raiders to save the land from being ravaged. The expeditions were usually led by the Danish kings, but they were composed by warriors from all over Scandinavia, and they eventually brought home more than 100 tons of silver. During the period when the Vikings extracted this money, the people of the English nation were not as skilled at sea-faring as their Scandinavian cousins, whose raiding voyages across the seas were financially lucrative but disrupted the lives in the communities they ravished. Perhaps the development of English maritime power was in part a response to their earlier vulnerability to Viking raids. It was the Norman Conquest in 1066 that moved England from out of the Scandinavian sphere of interest, although William actually paid Danegeld to Sweyn II of Denmark and may well have commissioned the great Domesday Book to find out how much money was available for further payments, if needed. England was never invaded again, however although she did not emerge as a sea-faring power until her own embroilment in European affairsâitself a legacy of the Norman invasionâended in the sixteenth century.[1] The term has come to be used as a warning and a criticism of any coercive payment, whether in money or kind. It resembled the type of moneys demanded by gangsters for so-called âprotection.â

Contemporary usage

The term has come to be used as a warning and a criticism of paying any coercive payment whether in money or kind.

In Britain the phrase is often coupled with the experience of Chamberlain's Appeasement of Hitler.[2]

To emphasize the point, people often quote two or more lines from the poem "Dane Geld" by Kipling as did Tony Parsons in The Daily Mirror, when criticizing the Rome daily La Repubblica for writing "Ransom was paid and that is nothing to be ashamed of," in response to the announcement that the Italian government paid $1 million for the release of two hostages in Iraq in October 2004.[3]

| â | That if once you have paid him the Danegeld,

|

â |

History

The first payment of the Danegeld to the Vikings took place in 856. English payment, of 10,000 pounds (3,732 kg) of silver, was also made in 991 following the Viking victory at the Battle of Maldon in Essex, when King Aethelred "The Unready" was advised by Archbishop Sigeric of Canterbury and the aldermen of the south-western provinces to buy off the Vikings rather than continue the armed struggle.

In 994 the Danes, under King Sweyn Forkbeard and Olaf Trygvason, returned and laid siege to London. They were once more bought off, and the amount of silver paid impressed the Danes with the idea that it was more profitable to extort payments from the English than to take whatever booty they could plunder.

Further payments were made in 1002, and especially in 1007 when Aethelred bought two years peace with the Danes for 36,000 pounds (13,436 kg) of silver. In 1012, following the capture and murder of the Archbishop of Canterbury, and the sack of Canterbury, the Danes were bought off with another 48,000 pounds (17,916 kg) of silver.

In 1016 Sweyn Forkbeard's son, Canute, became King of England. After two years he felt sufficiently in control of his new kingdom to the extent of being able to pay off all but 40 ships of his invasion fleet, which were retained as a personal bodyguard, with a huge Danegeld of 72,000 pounds (26,873 kg) of silver collected nationally, plus a further 10,500 pounds (3,919 kg) of silver collected from London.

William the Conqueror paid Danegeld to Sweyn II of Denmark and may well have commissioned the great Domesday Book to find out how much money was available for further payments, if needed. He replaced what had been an annual Denegeld tax with a land tax in 1116, the last year in which Danegeld was levied.

This kind of extorted tribute was not unique to England: according to Snorri Sturluson and Rimbert, Finland and the Baltic states (Grobin) paid the same kind of tribute to the Swedes. In fact, the Primary Chronicle relates that the regions paying protection money extended east towards Moscow, until the Finnish and Slavic tribes rebelled and drove the Varangians overseas. Similarly, the Sami peoples were frequently forced to pay tribute in the form of pelts. A similar procedure also existed in Iberia, where the contemporary Christian states were largely supported on tribute gold from the taifa kingdoms.[4]

The total cost

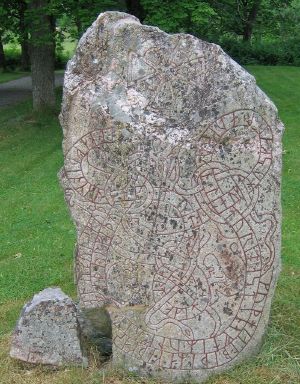

It is estimated that the total amount of money paid by the Anglo-Saxons amounted to some sixty million pence. More Anglo-Saxon pence of this period have been found in Sweden than in England and at the farm where the runestone Sö 260 talks of a voyage in the West, a hoard of several hundred English coins was found.

Arts

Shakespeare

William Shakespeare made reference to Danish tribute in Hamlet, Prince of Denmark, Act 3, scene 1 (King Claudius is talking of Prince Hamlet's insanity):

- ...he shall with speed to England,

- For the demand of our neglected tribute

Kipling

Danegeld is the subject of a poem by Rudyard Kipling. It ends in the following words:

| â |

It is wrong to put temptation in the path of any nation,

So when you are requested to pay up or be molested,

"We never pay any-one Dane-geld,

For the end of that game is oppression and shame,

|

â |

Notes

- â Following England's loss of her last French possession, Calais in 1558, the English began to look elsewhere for territorial expansion, beginning in North America.

- â Mr. Brady, House of Commons Hansard Debates for 25 Jan 2000 (pt 30) Column 233, "There are many examples of appeasement in history, whether it be the danegeld or more recently, and we know that appeasement does not work." Retrieved February 6, 2008.

- â Tony Parsons, We'll all pay for ransom,â Daily Mirror, October 4, 2004.

- â The Muslim taifa kingdoms paid parias, a tribute in lieu of raids (razzias).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Jansson, Sven B. Runstenar. STF, Stockholm, 1980. ISBN 9171560157

- Kipling, Rudyard. Dane-Geld A.D. 980â1016 Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- Round, John Horace. Danegeld and the Finance of Domesday; Notes on the Domesday Measures of Land; an Early Reference to Domesday. Domesday Studies, 1. 1888.

- Shakespeare, William. âThe Tragedy of Hamlet: Prince of Denmarkâ at MIT Hamlet, Act 3, scene 1.

- Webb, Philip Carteret. A Short Account of Danegeld With Some Further Particulars Relating to Will. the Conqueror's Survey. London, 1756. A Short Account of Danegeld Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- Williams, Ann. Ăthelred the Unready The Ill-Counselled King. London: Hambledon and London, 2003. ISBN 978-1852853822

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.