Difference between revisions of "Deism" - New World Encyclopedia

m (→Beginnings: ; Took out title of Herbert's book) |

|||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

===Beginnings=== | ===Beginnings=== | ||

| − | Thinking which could be described as Deistic has existed since antiquity, and can be identified in the works of [[Pre-Socratic philosophy|pre-Socratic philosophers]] such as [[Heraclitus]]. However, it was not until the time of the European [[Enlightenment]] with its newfound emphases on rigorous skepticism, deductive logic, and empiricism, that deism came into its own as a subject of philosophical discourse. The foundations of the Deist movement as were laid by Lord Herbert of Cherbury (1583-1648) | + | Thinking which could be described as Deistic has existed since antiquity, and can be identified in the works of [[Pre-Socratic philosophy|pre-Socratic philosophers]] such as [[Heraclitus]]. However, it was not until the time of the European [[Enlightenment]] with its newfound emphases on rigorous skepticism, deductive logic, and empiricism, that deism came into its own as a subject of philosophical discourse. The foundations of the Deist movement as were laid by Lord Herbert of Cherbury (1583-1648) who distinguished five principles of primary character within all religious traditions. These primary principles are 1) that God exists, 2) it is the duty of humans to worship him, 3) virtuous practice involves doing him honour, 4) man is under obligation to repent his sins, and 5) that there will be rewards and punishments after death based on earthly deeds. Further, Lord Herbert asserted that human reason was sufficient for purposes of attaining certainty with regard to fundamental religious truths. He also insisted that religion should be deeply involved in practical duties. Deistic writers that that followed Lord Herbert enlarged these themes, particularly the postulation that natural reason should be the establishment for religion. |

The independent works of other seventeenth century figures also had a hand in affecting the rise of Deism. Although [[Thomas Hobbes]] (1588-1679) was generally opposed to the concept of natural religion, the philosophical concepts he developed provided a new set of criteria through which to evaluate religions. Through his postulations that all legitimate human knowledge stemmed from sense data, he championed rational thought against ecclesiastical authority. Furthermore, the Cambridge Platonists, reacting to the increased influece of anti-rationalist dogmatism among the Puritan divines and the narrowly materialist writings of [[Thomas Hobbes|Hobbes]], put forward what they conceived to be a set of rational grounds for Christianity. Eschewing these philosophical pressures, they used Platonism to argue for human reason as the paramount receptacle for Divine revelation. | The independent works of other seventeenth century figures also had a hand in affecting the rise of Deism. Although [[Thomas Hobbes]] (1588-1679) was generally opposed to the concept of natural religion, the philosophical concepts he developed provided a new set of criteria through which to evaluate religions. Through his postulations that all legitimate human knowledge stemmed from sense data, he championed rational thought against ecclesiastical authority. Furthermore, the Cambridge Platonists, reacting to the increased influece of anti-rationalist dogmatism among the Puritan divines and the narrowly materialist writings of [[Thomas Hobbes|Hobbes]], put forward what they conceived to be a set of rational grounds for Christianity. Eschewing these philosophical pressures, they used Platonism to argue for human reason as the paramount receptacle for Divine revelation. | ||

| Line 91: | Line 91: | ||

*[http://www.templeofreason.org Temple of Reason] | *[http://www.templeofreason.org Temple of Reason] | ||

| − | == References == | + | ==References== |

*Collins, Anthony. ''A Discourse of the Grounds and Reasons of the Christian Religion''. New York : Garland Publishing, 1976. '''(ISBN numbers needed)''' | *Collins, Anthony. ''A Discourse of the Grounds and Reasons of the Christian Religion''. New York : Garland Publishing, 1976. '''(ISBN numbers needed)''' | ||

| − | |||

*Joyce, Gilbert Cunningham. “Deism” ''Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics''. James Hastings, ed. Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1910. 334-345. | *Joyce, Gilbert Cunningham. “Deism” ''Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics''. James Hastings, ed. Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1910. 334-345. | ||

*Tindal, Matthew. ''Christianity as Old as the Creation''. Whitefish, MT: Kessinger Publishing, 2005. | *Tindal, Matthew. ''Christianity as Old as the Creation''. Whitefish, MT: Kessinger Publishing, 2005. | ||

*Toland, John. ''John Toland's Christianity Not Mysterious: Text, Associated Works and Critical Essays''. Alan Harrison, Richard Kearney, Philip McGuinness, Eds. Dublin: Lilliput Press, 1998. | *Toland, John. ''John Toland's Christianity Not Mysterious: Text, Associated Works and Critical Essays''. Alan Harrison, Richard Kearney, Philip McGuinness, Eds. Dublin: Lilliput Press, 1998. | ||

*Walters, Kerry S. ''Rational Infidels: The American Deists''. Durango, CAL: Longwood Academic, 1992. | *Walters, Kerry S. ''Rational Infidels: The American Deists''. Durango, CAL: Longwood Academic, 1992. | ||

| + | * Wood, Allen W. "Deism." ''Encyclopedia of Religion'', Mercia Eliade, ed. New York: MacMillan Publishing, 1987. | ||

Revision as of 17:51, 9 May 2006

Deism (from the Latin deus for God) refers to both a type of belief in a God who created and designed the universe and it's natural laws but who does not interfere in its daily operation, and an historical movement stemming from modern Christianity which peaked in popularity during the eighteenth century, and taught that reason, rather than revelation or tradition, should be the basis of religion. Deists see God as the creator of the universe and first-cause who can be known through reason and natural law. However, they believe that once creation ended, God's active involvement in the universe also ended. In this manner, God is seen as analogous to a distant Landlord who does not visit his or her tenets but whose presence is still visible in the grain or thread of all creation. While deism elevates the role of reason as a tool for understanding God, it does so at the expense of providential theology. Deism has been criticized for neglecting the commonly held idea of progressive revelation as well as the view that God's active involvement in the cosmic unfolding of restoration and evolutionary spiritual progression towards a higher endtime.

Deism as a Religious Classification

Deism can be used to describe a general philosophy concerning the nature of God and the cosmos. Philosophical deism acknowledges belief in a creator God, the First Cause who brought the universe into existence. The process of ceation is outlined in the argument from design. In this theory, God is referred to by heavily anthropomorphic terminology, construed as a real person, standing over the world of humanity. For example, God is like the watchmaker (or the Primordial Architect, in Sir Isaac Newton's terms); much as the watchmaker fashions the parts and functions of the watch, God similarly puts in place the machinations of the universe, and provides the energy which sets the universe in motion. While God is the source of all motion and matter, Deists believe God's intercession into his creation only occurs occasionally, if occurring at all. God's role, in the mind of the deist, is merely to create the universe and the laws which operate it, and afterwards to allow these laws to take their course without His assistance. Just as nature, humans also exist fully independent of their maker after creation, and as such, philosophical deism places emphasis on the freedom of human choice.

In the sphere of morality, God is conceived of by deists as the supreme authority of the moral world. Just as God laid down the laws governing the physical universe, He sets in place the moral order, as well. In this capacity, he serves as the judge of all moral beings within the cosmos, however, he does not necessarily become involved in the enforcement of the law. Instead, humans are punished and rewarded as a function of their own observance of the laws. Disobedience to God's laws will result in negative consequences for the moral being, thus God's intervention is not required in the distribution of punishment. It is human reason which replaces the continual advent of God, since a human being's moral welfare in the deist philosophy is based upon the accuracy of their knowledge of the laws by which the course of the world is determined, including what constitutes good and what constitutes evil.

History of Deism

Beginnings

Thinking which could be described as Deistic has existed since antiquity, and can be identified in the works of pre-Socratic philosophers such as Heraclitus. However, it was not until the time of the European Enlightenment with its newfound emphases on rigorous skepticism, deductive logic, and empiricism, that deism came into its own as a subject of philosophical discourse. The foundations of the Deist movement as were laid by Lord Herbert of Cherbury (1583-1648) who distinguished five principles of primary character within all religious traditions. These primary principles are 1) that God exists, 2) it is the duty of humans to worship him, 3) virtuous practice involves doing him honour, 4) man is under obligation to repent his sins, and 5) that there will be rewards and punishments after death based on earthly deeds. Further, Lord Herbert asserted that human reason was sufficient for purposes of attaining certainty with regard to fundamental religious truths. He also insisted that religion should be deeply involved in practical duties. Deistic writers that that followed Lord Herbert enlarged these themes, particularly the postulation that natural reason should be the establishment for religion.

The independent works of other seventeenth century figures also had a hand in affecting the rise of Deism. Although Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) was generally opposed to the concept of natural religion, the philosophical concepts he developed provided a new set of criteria through which to evaluate religions. Through his postulations that all legitimate human knowledge stemmed from sense data, he championed rational thought against ecclesiastical authority. Furthermore, the Cambridge Platonists, reacting to the increased influece of anti-rationalist dogmatism among the Puritan divines and the narrowly materialist writings of Hobbes, put forward what they conceived to be a set of rational grounds for Christianity. Eschewing these philosophical pressures, they used Platonism to argue for human reason as the paramount receptacle for Divine revelation.

Similar to Hobbes, John Locke (1632-1704) had an unintentional effect on Deistic thought. In his work Reasonableness of Christianity, he delineated the progression of Christian doctrine through history. In doing so he provided some discrimination between the valuable and worthless elements of the Creed, showing particular skepticism toward elements of the Biblical texts which involve miracles and revelation; further, he conceived the Christian religion to be a powerful moral philosophy rather than means to invigorate the human will with spirit. Although each of these ideas had been formulated prior to Locke's publication, this was the first instance where they were combined systematically. Locke arrived at the conclusion that religion in the form that it currently existed was in need of extensive modification. Hence, the foundations for the Deist movement had been laid.

Newtonian physics, the intellectual basis for the scientism of the Enlightenment, propogated the idea that matter behaves in a mathematically predictable manner that can be understood by postulating and identifying laws of nature. Concepts borrowed from the observational methods of science such as objectivity, natural equality, and the prescription to treat like cases similarly were central principles of the Enlightenment, and became the rubric for scrutinizing all domains of life during this time period. Inevitably, these principles came to inform the reinterpretation of religion, as well, which resulted in the synthesis of deism. Furthermore, exasperation as a result of the immense toll centuries of religious warfare had taken upon Europe provided a powerful impetus for placing a more rational framework upon spiritual matters.

Popularity in England

The height of Deist popularity occurred in England during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The first explicitly Deistic work was John Toland's Christianity Not Mysterious, (1696), which drew upon some of Locke's postulations, stressing a process whereby Truth was inferred from nature rather than revelations directly from the divine. Anything a reader of the scriptures could not comprehend through common sense was to be considered false, in Toland's view. Toland meticulously studied the Gospels and clarified every part of them which seemed contrary to reason. Reason, Toland asserted, was to be of primary importance not only in everyday life, but in all matters religious, as well. The publication of Toland's ideas caused much uproar throughout Britain. The Irish parliament, for example, ordered mass burning of the book, while English ecclesiastical authorities declared it essentially anti-Christian in its denial of miracles. However, the seed of deism had been sewn: Toland had incited the process of undermining the credibility of early Christian literature as a whole, suggesting that they were, for the most part, works of superstition that should be reconsidered.

Shortly after in 1713, Anthony Collins published Discourse of Freethinking occassioned by the Rise and Growth of a sect Called Freethinkers. Collins' work went beyond Toland's in attempting to justify the claim that rational inquiry made for virtually limitless freedom for human beings when compared to moral and religious ruminations. Collins ascertained that the Deistic argument rested upon a decision to place a focus on individual liberty in the pursuit of moral investigation, as well as a focus on the individual capacity to discover moral truth. Collins argued that all the great moral pedagouges such as the prophets, Paul, and Jesus Himself taught their disciples by appealing to reason, rather than fear. In contrast, the Church and the State had cultivated fear through superstitious beliefs in order to inspire humans to behave morally, and in the process had created what Toland viewed to be moral corruption. His prescription for religious reform was to excise such fear-inducing superstitions from religious teaching, and to concentrate on the development of morality through rationality in each individual. Moreover, in a later work, Discourse of the Grounds and Reason of Christian Religion, Collins turned the focus to the consideration of whether or not prophecy and miracle are credible phenomena. Specifically, this debate centered around an idea which had been widely accepted up until that time: the notion that the correspondence of Old Testament prophecy and [[New Testament] events were adquate proof of Christianity's truth. Collins challenged this, as he questioned the authenticity and accuracy of events such as those in the Gospels which were supposedly dictated by New Testament writers such as the Apostles. If the miracles reported by these authors were to remain in religious discourse, Collins suggested they be reinterpreted as allegory or metaphor to supplement the more reasonable contributions of Christ and other religious figures. Collins perpetuated suspicions toward the veracity of biblical documents, and provided further momentum for biblical criticism.

In 1730 Matthew Tindal published Christianity as Old as the Creator, a book which marked what was probably the culmination of all Deist thought. Tindal further shaped the Deist arguments developed by the thinkers who preceded him, though he managed to synthesize the various strands together and present them in more intelligible langauge than his predecessors had. He further repudiated the mysterious aspects of religion and promoted a general distrust toward religious authority. The ultimate value of religion, he contended, was to aid humans in fashioning their own personal beliefs and to cultivate their moral nature, rather than encouraging them to depend on revelation. He held that in the context of their moral faculties, all humans were equal in the eyes of God at all times. Further, through the gift of reason, humans held the ability to comprehend the consequences of their actions without the continual assistance of God. For Tindal, human duties are evident through the the reason behind things and their relationships with one another. It is upon these natural foundations that religions is constructed. Religion, in Tindal's view, was quite simply a law of nature adapted to accomodate the given circumstances of humankind; that is, religion was seen as what naturally arises from consideration of god. It was in such natural reflections that religious edifices were to be constructed, and very little else. Tindal held that no command communicated by revelation could be superior to the natural workings of nature, because no command was to be seen as obligatory unless its reasonableness was blatantly evident. Corollary with this point, placing anything in religion which is not demonstrable by reason Tindal considered to be an insult to the faculties of human beings and ultimately a defamation of the honour of God.

Popularity Abroad

Deism found even more welcoming environments outside of England. French Enlightenment thinkers such as Voltaire and Rousseau found the ideas particularly appealing and introduced some new elements of their own. Voltaire used Deism as a vehicle for expressing resentment against the social repression perpetuated by the Catholic Church in France. Of course, the internal passions of the French were already at a peak due to the impending revolution, and Deism fed upon this, becoming identified with the broader anti-ecclesiastical movement. Rather than transforming theology of the Church as the English Deists had, the French advocated an eschewal of theology altogether. In place of the Catholic Church, they suggested a non-dogmatic religion with Deist ideals be inserted. This attempt eventually failed, as the French variation of Deism gradually evolved into a form of materialism devoid of any large scale religiosity. Rousseau made similar attempts to instill Deism within French life, but also had little success.

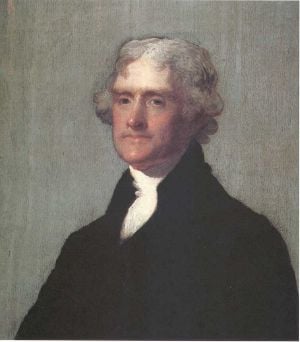

Since America was supposedly championed on the ideals of equality and reason, it is not surprising that numerous founding fathers of the nation such as Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin and George Washington identified themselves as deists. In fact, the first six presidents of the United States, as well as four later ones, had strong deistic beliefs. Jefferson even attempted to produce his own variation of biblical scripture with the publication of the so-called "Jefferson Bible", also known as The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth. Jefferson composed this volume by removing sections of the New Testament containing supernatural aspects. Also, he excised portions which he interpreted to be misrepresentations or additions that had been made by the writers of the Gospels. What was left, supposedly, was a completely reasonable version of the doctrine of Jesus, featuring only those parts conceivable to rationalistic Deist readers.

In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the newly developing land of America was dominated by Protestant Christianity. Some held the Christian masses in contempt, perceiving their majority as a threat to the Enlightenment ideals of equality and rationality America was built upon. Many of these dissatisfied inviduals sought recourse in Deist ideals; hence, the popularity of Deist thought, which was by this time subsiding in England, was recapitulated on American soil. In 1790, Elihu Palmer, a one-time Baptist minister, launched a nation-wide crusade for Deism. By the turn of the century, Deism had grown in popularity and started to become more accepted among the populace of mainstream America, even rivalling main-stream Christianity. This caused a vociferous backlash from the Christian establishment, which only served to pique the interest of some congregation members who promptly jumped ship to join the Deists. Well into the nineteenth century, Deism continued to flourish in America.

Decline in popularity

Numerous factors contributed to a general decline in the Deism's popularity. Most notably, the writings of David Hume increased doubt about the sturdiness of the First Cause argument and the argument from design. In formulating his critique, Hume targeted the fundamental assumption of Deism: that religon was based on natural principles of creation and therefore had been complete from the time of creation itself. In counterpoint, Hume noted how early religion would most likely have been barbarous and inchoate. Only through the attempt to explain natural phenomena would these early absurdities progressively be done away with. Hume had the benefit of the doubt in the eyes of the intellectual populace, as he could produce evidence from earlier religion in light of new anthropological findings. Further, Hume defeated the the idea of a Primordial Architect, attributing the widespread belief in such a creator god to irrational superstitions. Later on, Charles Darwin's theory of natural selection would do further damage to this idea. The deleterious effects such criticisms had upon Deist affiliation illustrate the extent to which Deism was based upon philosophical principles rather than deep religious faith.

Movements both within and without mainstream Christianity also took away from the popularity of Deism. Several Christian Great Awakenings in America won over deists, especially those among denominations that professed a more personal relationship with Christ, and who argued that prayer could alter events. Such a personal notion of divinity seems to prove refreshing for some Deists. Moreover, the rise of Unitarianism, converted many Deist sympathizers. This could be expected, as the Unitarians adopted many of the Deist ideas. Furthermore, pointedly anti-deist and anti-reason campaigns were organized by some Christian clergymen to vilify and equate deism with atheism in public opinion. Such developments reflected a general realization in the nineteenth century that reason and rationalism could not solve all of humanity's problems. As emotion became an important component of life again in the Age of Romanticism, Deist ideals subsided.

Contemporary status

Newtonian physics, when simplified, is considered deterministic. Over the past several decades it has been largely superceded by newer theories in physics, most notably quantum mechanics, which has been commonly interpreted as non-deterministic. Since deism is so deeply rooted in the Newtonian mode of thinking, any further philosophical development has been greatly impeded by these philosophical shifts in modern science. Some modern revivals of deism such as pantheism and panentheism have been spurred in limited numbers, usually relying on the internet for recruiting members and rarely becoming reified as corporate religious communities. However, some Unitarian Universalists are currently resurrecting deist ideals in order to counter the recent popularity of Christian Fundamentalism.

Contributions of Deism

Despite the significant decline in popularity, Deism still holds an important place in religious history as both a philosophy and an historical movement. No movement gave reason and rationality such importance in religion as the Deists did. Deists made religious scripture and doctrine fair game for literary criticism and scientific analysis. Furthermore, Deists made it evident that while God is important, so too is the human being who conceives of God. Deists combined the common sense of humans with the trained skill of intellectuals so as not to lose the virtues of humanity in total submission to God. This was particularly helpful in the times of great technological advancement contemporaneous with the Deist movement. Conversely, by concentrating so heavily on intellectualism and reason, Deists also made evident the importance of emotion as a stimulant for faith. Later religious systems, such as the Wesleyan movement, were no doubt conscious of the rise and decline of Deism in their attempts to balance reason and faith in their own beliefs.

See also

- Cosmological argument

- Cosmotheism

- Evolutionary Creationism

- Freethought

- Ignosticism

- List of deists

- Panendeism

- Panentheism

- Pantheism

- Philosophical theism

- Polydeism

- Transcendentalism

- Transtheism

External links

External informational links

- DEISTPEDIA: The Deist Encyclopedia

- DEISM: The Union of Reason and Spirituality

- Deism and Reason

- Of the Religion of Deism Compared with the Christian Religion by Thomas Paine

- The Age of Reason by Thomas Paine

- Definition of deism from The Dictionary of the History of Ideas at the University of Virginia

- English Deism - Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- French Deism - Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- religious tolerance.org article on Deism

External organization links

- Deism and Reason

- Positive Deism

- Dynamic Deism

- PONDER

- Deist.info

- World Union of Deists

- Aldeism

- American/ Unitarian Conference

- Temple of Reason

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Collins, Anthony. A Discourse of the Grounds and Reasons of the Christian Religion. New York : Garland Publishing, 1976. (ISBN numbers needed)

- Joyce, Gilbert Cunningham. “Deism” Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics. James Hastings, ed. Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1910. 334-345.

- Tindal, Matthew. Christianity as Old as the Creation. Whitefish, MT: Kessinger Publishing, 2005.

- Toland, John. John Toland's Christianity Not Mysterious: Text, Associated Works and Critical Essays. Alan Harrison, Richard Kearney, Philip McGuinness, Eds. Dublin: Lilliput Press, 1998.

- Walters, Kerry S. Rational Infidels: The American Deists. Durango, CAL: Longwood Academic, 1992.

- Wood, Allen W. "Deism." Encyclopedia of Religion, Mercia Eliade, ed. New York: MacMillan Publishing, 1987.