Difference between revisions of "Court Jew" - New World Encyclopedia

(New page: {{Jew}} '''Court Jew''' ''(from German: Hofjude(n), Hoffaktor)'' is a term for historical Jewish bankers or businessmen who lent money and handled the finances of some of the [[Chr...) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (52 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Images OK}}{{submitted}}{{approved}}{{copyedited}} |

| − | '''Court Jew' | + | [[Image:Samson Wertheimer portrait.jpg|thumb|right|Rabbi Samson Wertheimer was both a court Jew and chief rabbi of Hungary and Moravia.]] |

| + | '''Court Jew''' is a term for [[Jew]]ish leaders who rose to positions of influence in [[Christian]] [[Europe]]an noble houses. The first historical examples of what would be later called "court Jews" emerged during the [[Renaissance]], when local rulers used services of wealthy Jews for short-term loans. Noble patrons of court Jews employed them as [[financier]]s, advisers, suppliers, [[diplomat]]s, and [[trade delegate]]s. Court Jews could use their family and community connections to supply their sponsors with loans of money and needed provisions, including food, clothing, spices, arms, [[ammunition]], and precious metals. | ||

| − | + | Some court Jews were also prominent people in the local Jewish community or even famous [[rabbi]]s. Righteous court Jews were noted [[philanthropist]]s who used their influence to help and protect their brethren, being the only Jews who could interact with the local high society and present petitions of the Jews to the ruler. | |

| − | + | In return for their services, court Jews gained social privileges—sometimes even titles—and could live outside the Jewish [[ghetto]]s. Moreover, because these were under noble protection, they were exempted from [[rabbi]]nical jurisdiction and thus did not have to adhere closely to [[halkha|Jewish law]]. This proved a mixed blessing, as some court Jews developed reputations, both among the Christian populace and their fellow Jews, as being unethical and greedy. Because they also lent money at [[interest]] to middle-class Christians and were often used by Christian rulers as tax collectors, the court Jew became a negative [[stereotype]] that fed into later Christian [[antisemitism]]. | |

| − | + | Moreover, due to the precarious social position of Jews, some nobles could simply ignore their debts to the court Jews and often blamed them for the nation's economic woes. Many debts were also canceled during [[pogroms]], when the Jewish creditor could disappear. If the sponsoring noble died, his Jewish financier could even face exile or execution. The last court Jews lived in the mid-nineteenth century, in Germany. | |

| − | + | ==Early court Jews== | |

| + | Although the Jews were expelled from [[England]], in 1290, by a decree of [[King Edward I]], the fictional character of "Isaac the Jew" in [[Sir Walter Scott]]'s''Ivanhoe'' may hearken back to a time when court Jews played a role in the English court. Jews also served at court in Muslim [[Spain]], but these are not counted among the court Jews of Europe. Some of the earliest known court Jews served in the Spanish and Portuguese courts. One such was [[Isaac Abrabanel]] (1437-1508), a noted biblical commentator who also served [[King Afonso V]] of Portugal as treasurer and strove to save his fellow Jews from the persecution in Spain. [[Abraham Zacuto]] (1450–1510), though not a financier, served in the Portuguese court as royal astronomer. [[Josel of Rosheim]] (1480-1554) was the great advocate of German and Polish Jews during the reigns of the Holy Roman emperors [[Maximilian I]] and [[Charles V]]. | ||

| − | + | == Position and influence== | |

| + | Despite the expulsion of the Jews from some European nations, court Jews played increasingly important parts at the courts of the Austrian emperors and the German princes in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and at the beginning of the nineteenth. Although some were men of learning and serious religious character, they were mostly wealthy businessmen, distinguished above their co-religionists by their commercial instincts and their adaptability. Court rulers treated them, on the one hand, as their favorites, and, on the other, as their whipping-boys. Court Jews frequently suffered through the denunciation of their envious rivals and fellow Jews, and were often the objects of hatred of the Gentile common people and courtiers. | ||

| − | + | The court Jews enjoyed special privileges as the agents of the rulers, and in times of war as the purveyors and treasurers of the state. They were under the jurisdiction of the court marshal, and were not compelled to wear the [[Yellow badge|Jews' badge]]. They were permitted to stay wherever the emperor held his court, and to live anywhere in the [[German empire]], even in places where no other Jews were allowed. Wherever they settled they could buy houses, slaughter meat according to the Jewish ritual, and maintain a [[rabbi]] if they wished. They could sell their goods wholesale and retail, and could not be taxed or assessed higher than the [[Christian]]s, as was the case with other Jews. | |

| − | |||

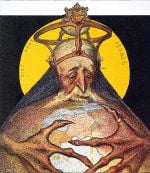

| − | + | [[Image:Antisemiticroths.jpg|thumb|left|150px|"Rothschild," by C. Léandre; France, 1898. Caricature of a court Jew as the icon of Jewish capitalism]] | |

| − | + | However, like all businessmen, court Jews functioned at the mercy of the prevailing economy and changes in economic conditions, over which they had little or no control. Nevertheless, they were often assigned blame for a ruler's financial woes. Particularly odious were their functions outside of the court as lenders to the Christian middle, working, and agricultural classes. Their sovereigns also sometimes assigned them the role of local [[tax]] collection. These roles built up a long-standing enmity between Jews and Christians. | |

| − | + | Christians were often encouraged, both by their rulers and the Church, to blame court Jews for the economic hardships that would periodically befall them. The high taxes demanded by the ruler to pay off his war debts were often blamed on the court Jews who had helped finance the war, even though they had no choice in the matter. When the ruler’s economic decisions resulted in a decline in national income or a rise in interest rates, the court Jews often received the brunt of the blame. | |

| − | + | From nineteenth century onward, the Christian culture of Europe would draw upon the historical [[stereotype]] of the court Jew and apply it to Jews in general. Resentment against “International Jewish Money-[[Capitalism]],” along with religious [[anti-Judaism]] and the infamous "[[blood libel]]" which blamed Jews for the deaths Christian children, fueled popular support for anti-Jewish policies. The most lasting and negative impact of this alleged indirect economic rule by Jews was the ingrained popular belief in a “hidden” hand of Jewish influence in domestic economic events caused by an even more “hidden” hand of international Jewish economic power. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

== At the Austrian court == | == At the Austrian court == | ||

| − | The [[Austria]]n emperors kept a considerable number of court Jews. Among those of Emperor [[Ferdinand II, Holy Roman Emperor|Ferdinand II]] | + | The [[Austria]]n emperors kept a considerable number of court Jews. Among those of Emperor [[Ferdinand II, Holy Roman Emperor|Ferdinand II]] (1578–1637), [[Mordecai Marcus Meisel]] (1528-1601) was a [[philanthropist]] and community leader at [[Prague]] whose great wealth aided the Austrian imperial house during the Turkish wars and helped his fellow Jews in times of difficulty. [[Jacob Bassevi von Treuenberg]] (1570-1634) was a Bohemian court Jew and factor (agent) who exerted his influence on behalf of the Jews in the [[Holy Roman Empire]] and Italy. Bassevi was the first Jew to be ennobled, with the title ''von Treuenberg''. [[Solomon Mayer|Solomon]] and [[Ber Mayer]] furnished the cloth for four squadrons of cavalry for the wedding of the emperor and [[Eleonora of Mantua]]. Other Austrian court Jews included [[Joseph Pincherle]] of [[Görz]], Moses and [[Joseph Marburger]] ([[Joseph Morpurgo|Morpurgo]]) of [[Gradisca d'Isonzo|Gradisca]], [[Ventura Pariente]] of [[Trieste]], the physician [[Elijah Chalfon]] of [[Vienna]], [[Samuel zum Drachen]], and [[Samuel zum Straussen]] of [[Frankfort-on-the-Main]]. |

| − | + | Another important court Jews was [[Samuel Oppenheimer]] (1630-1703), who was a banker, imperial court financier, diplomat, and military supplier who enjoyed special favor of Emperor [[Leopold I]]. Oppenheimer won the right of a limited number of Jews to return to Vienna after their expulsion and used his influence to win the court and the [[Jesuits]] to the side of the Jews during an attempt to repress the [[Talmud]] as anti-Christian. | |

| − | Samson Wertheimer | + | Oppenheimer and [[Samson Wertheimer]] (1658-1724) loaned millions of [[florin]]s to the [[House of Hapsburg]] for provisions, munitions, and other military needs during the Rhenish, French, Turkish, and Spanish wars. Wertheimer, who was also the chief rabbi of Hungary and Moravia, also held the title of chief court factor to the [[Prince-elector|elector]]s of [[Mayence]], the [[Electoral Palatinate|Palatinate]], and [[Treves]]. He received from emperor Leopold a chain of honor with his miniature. |

| − | + | Samson Wertheimer was succeeded as court factor by his son, Wolf. Contemporaneous with him was [[Leffmann Behrends]] (also called [[Liepmann Cohen]]) of [[Hanover]], court factor and agent of Elector [[Ernest Augustus, Elector of Brunswick-Lüneburg|Ernest Augustus]] and of Duke [[Rudolf August of Brunswick]]. He also had relationships with several other rulers and high dignitaries. Behrends' two sons received the same titles as he, chief court factors and agents. [[Issachar Behrend Lehman]] was a court factor of [[Saxony]], and his son, Lehman Behrend, was called to [[Dresden]] as court factor by King [[Augustus]] the Strong. [[Moses Bonaventura]] of Prague was also court Jew of Saxony. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | The Models were a family of court Jews of the [[margrave]]s (rulers) of [[Ansbach]] about the middle of the seventeenth century. Especially influential was [[Marx Model]], who had the largest business in the whole principality and extensively supplied the court and the army. He fell into disgrace through the intrigues of another court Jew, [[Elkan Fränkel]], a member of a wealthy family that had been driven from [[Vienna]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | == Later court Jews== | |

| + | The Great Elector, [[Frederick William, Elector of Brandenburg|Frederick William]], also kept a court Jew at Berlin, [[Israel Aaron]] (d. 1670), who used his influence to prevent the influx of foreign Jews into the Prussian capital. Other court Jews of the elector were Gumpertz, [[Berend Wulff]], and [[Solomon Fränkel]]. | ||

| − | + | [[Image:Jacobson.gif|thumb|left|150px|Israel Jacobson, one of the last court Jews]] | |

| − | + | A particularly influential court Jew of this period was [[Jost Liebmann]]. Through his marriage with the widow of the above-mentioned Israel Aaron, he succeeded to the latter's position after his death and was highly esteemed by the elector. He had continual quarrels with the court Jew of the crown prince, [[Markus Magnus]]. After Liebmann's death his influential position fell to his widow, known as Liebmannin, who was so well received by the future [[Frederick I of Prussia|Frederick I]] of [[Prussia]] that she could go unannounced into his cabinet. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | In | + | There were also court Jews at all the petty German courts. [[Zacharias Seligmann]] (1694) worked in the service of the prince of [[Hesse-Homburg]], and others served in the courts of the dukes of [[Mecklenburg]]. Others mentioned toward the end of the seventeenth century are Bendix and [[Ruben Goldschmidt]] of Homburg, [[Moses Israel Fürst]], [[Michael Hinrichsen]] of [[Glückstadt]], and his son, [[Reuben Hinrichsen]]. In the mid eighteenth century, the Jewish agent Wolf lived at the court of Frederick III of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. |

| − | + | The last actual court Jews were [[Israel Jacobson]], court agent of [[Braunschweig|Brunswick]], and [[Wolf Breidenbach]], factor to the [[Elector of Hesse]], both of whom occupy honorable positions in the history of the Jews. Jacobsen (1768-1828) was a noted philanthropist who was influential in the establishment of [[Reform Judaism]], while Breidenbach (d. 1829) was a champion of Jewish emancipation. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == | + | == References == |

| − | * | + | * Mann, Vivian B., Richard I. Cohen, and Fritz Backhaus. ''From Court Jews to the Rothschilds: Art, Patronage, and Power: 1600-1800''. Munich: Prestel, 1996. ISBN 9783791316246. |

| − | * | + | * Stern, Selma. ''The Court Jew: A Contribution to the History of the Period of Absolutism in Europe''. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Books, 1985. ISBN 9780887380198. |

| − | + | * Vries, B.W. de. ''Of Mettle and Metal: From Court Jews to World-Wide Industrialists''. Amsterdam: NEHA, 2000. ISBN 9789057420290. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

*{{JewishEncyclopedia}} | *{{JewishEncyclopedia}} | ||

| − | [[Category: | + | [[category:religion]] |

| + | [[Category:Judaism]] | ||

| + | [[Category:history]] | ||

{{Credit|189016932}} | {{Credit|189016932}} | ||

Latest revision as of 20:25, 28 May 2020

Court Jew is a term for Jewish leaders who rose to positions of influence in Christian European noble houses. The first historical examples of what would be later called "court Jews" emerged during the Renaissance, when local rulers used services of wealthy Jews for short-term loans. Noble patrons of court Jews employed them as financiers, advisers, suppliers, diplomats, and trade delegates. Court Jews could use their family and community connections to supply their sponsors with loans of money and needed provisions, including food, clothing, spices, arms, ammunition, and precious metals.

Some court Jews were also prominent people in the local Jewish community or even famous rabbis. Righteous court Jews were noted philanthropists who used their influence to help and protect their brethren, being the only Jews who could interact with the local high society and present petitions of the Jews to the ruler.

In return for their services, court Jews gained social privileges—sometimes even titles—and could live outside the Jewish ghettos. Moreover, because these were under noble protection, they were exempted from rabbinical jurisdiction and thus did not have to adhere closely to Jewish law. This proved a mixed blessing, as some court Jews developed reputations, both among the Christian populace and their fellow Jews, as being unethical and greedy. Because they also lent money at interest to middle-class Christians and were often used by Christian rulers as tax collectors, the court Jew became a negative stereotype that fed into later Christian antisemitism.

Moreover, due to the precarious social position of Jews, some nobles could simply ignore their debts to the court Jews and often blamed them for the nation's economic woes. Many debts were also canceled during pogroms, when the Jewish creditor could disappear. If the sponsoring noble died, his Jewish financier could even face exile or execution. The last court Jews lived in the mid-nineteenth century, in Germany.

Early court Jews

Although the Jews were expelled from England, in 1290, by a decree of King Edward I, the fictional character of "Isaac the Jew" in Sir Walter Scott'sIvanhoe may hearken back to a time when court Jews played a role in the English court. Jews also served at court in Muslim Spain, but these are not counted among the court Jews of Europe. Some of the earliest known court Jews served in the Spanish and Portuguese courts. One such was Isaac Abrabanel (1437-1508), a noted biblical commentator who also served King Afonso V of Portugal as treasurer and strove to save his fellow Jews from the persecution in Spain. Abraham Zacuto (1450–1510), though not a financier, served in the Portuguese court as royal astronomer. Josel of Rosheim (1480-1554) was the great advocate of German and Polish Jews during the reigns of the Holy Roman emperors Maximilian I and Charles V.

Position and influence

Despite the expulsion of the Jews from some European nations, court Jews played increasingly important parts at the courts of the Austrian emperors and the German princes in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and at the beginning of the nineteenth. Although some were men of learning and serious religious character, they were mostly wealthy businessmen, distinguished above their co-religionists by their commercial instincts and their adaptability. Court rulers treated them, on the one hand, as their favorites, and, on the other, as their whipping-boys. Court Jews frequently suffered through the denunciation of their envious rivals and fellow Jews, and were often the objects of hatred of the Gentile common people and courtiers.

The court Jews enjoyed special privileges as the agents of the rulers, and in times of war as the purveyors and treasurers of the state. They were under the jurisdiction of the court marshal, and were not compelled to wear the Jews' badge. They were permitted to stay wherever the emperor held his court, and to live anywhere in the German empire, even in places where no other Jews were allowed. Wherever they settled they could buy houses, slaughter meat according to the Jewish ritual, and maintain a rabbi if they wished. They could sell their goods wholesale and retail, and could not be taxed or assessed higher than the Christians, as was the case with other Jews.

However, like all businessmen, court Jews functioned at the mercy of the prevailing economy and changes in economic conditions, over which they had little or no control. Nevertheless, they were often assigned blame for a ruler's financial woes. Particularly odious were their functions outside of the court as lenders to the Christian middle, working, and agricultural classes. Their sovereigns also sometimes assigned them the role of local tax collection. These roles built up a long-standing enmity between Jews and Christians.

Christians were often encouraged, both by their rulers and the Church, to blame court Jews for the economic hardships that would periodically befall them. The high taxes demanded by the ruler to pay off his war debts were often blamed on the court Jews who had helped finance the war, even though they had no choice in the matter. When the ruler’s economic decisions resulted in a decline in national income or a rise in interest rates, the court Jews often received the brunt of the blame.

From nineteenth century onward, the Christian culture of Europe would draw upon the historical stereotype of the court Jew and apply it to Jews in general. Resentment against “International Jewish Money-Capitalism,” along with religious anti-Judaism and the infamous "blood libel" which blamed Jews for the deaths Christian children, fueled popular support for anti-Jewish policies. The most lasting and negative impact of this alleged indirect economic rule by Jews was the ingrained popular belief in a “hidden” hand of Jewish influence in domestic economic events caused by an even more “hidden” hand of international Jewish economic power.

At the Austrian court

The Austrian emperors kept a considerable number of court Jews. Among those of Emperor Ferdinand II (1578–1637), Mordecai Marcus Meisel (1528-1601) was a philanthropist and community leader at Prague whose great wealth aided the Austrian imperial house during the Turkish wars and helped his fellow Jews in times of difficulty. Jacob Bassevi von Treuenberg (1570-1634) was a Bohemian court Jew and factor (agent) who exerted his influence on behalf of the Jews in the Holy Roman Empire and Italy. Bassevi was the first Jew to be ennobled, with the title von Treuenberg. Solomon and Ber Mayer furnished the cloth for four squadrons of cavalry for the wedding of the emperor and Eleonora of Mantua. Other Austrian court Jews included Joseph Pincherle of Görz, Moses and Joseph Marburger (Morpurgo) of Gradisca, Ventura Pariente of Trieste, the physician Elijah Chalfon of Vienna, Samuel zum Drachen, and Samuel zum Straussen of Frankfort-on-the-Main.

Another important court Jews was Samuel Oppenheimer (1630-1703), who was a banker, imperial court financier, diplomat, and military supplier who enjoyed special favor of Emperor Leopold I. Oppenheimer won the right of a limited number of Jews to return to Vienna after their expulsion and used his influence to win the court and the Jesuits to the side of the Jews during an attempt to repress the Talmud as anti-Christian.

Oppenheimer and Samson Wertheimer (1658-1724) loaned millions of florins to the House of Hapsburg for provisions, munitions, and other military needs during the Rhenish, French, Turkish, and Spanish wars. Wertheimer, who was also the chief rabbi of Hungary and Moravia, also held the title of chief court factor to the electors of Mayence, the Palatinate, and Treves. He received from emperor Leopold a chain of honor with his miniature.

Samson Wertheimer was succeeded as court factor by his son, Wolf. Contemporaneous with him was Leffmann Behrends (also called Liepmann Cohen) of Hanover, court factor and agent of Elector Ernest Augustus and of Duke Rudolf August of Brunswick. He also had relationships with several other rulers and high dignitaries. Behrends' two sons received the same titles as he, chief court factors and agents. Issachar Behrend Lehman was a court factor of Saxony, and his son, Lehman Behrend, was called to Dresden as court factor by King Augustus the Strong. Moses Bonaventura of Prague was also court Jew of Saxony.

The Models were a family of court Jews of the margraves (rulers) of Ansbach about the middle of the seventeenth century. Especially influential was Marx Model, who had the largest business in the whole principality and extensively supplied the court and the army. He fell into disgrace through the intrigues of another court Jew, Elkan Fränkel, a member of a wealthy family that had been driven from Vienna.

Later court Jews

The Great Elector, Frederick William, also kept a court Jew at Berlin, Israel Aaron (d. 1670), who used his influence to prevent the influx of foreign Jews into the Prussian capital. Other court Jews of the elector were Gumpertz, Berend Wulff, and Solomon Fränkel.

A particularly influential court Jew of this period was Jost Liebmann. Through his marriage with the widow of the above-mentioned Israel Aaron, he succeeded to the latter's position after his death and was highly esteemed by the elector. He had continual quarrels with the court Jew of the crown prince, Markus Magnus. After Liebmann's death his influential position fell to his widow, known as Liebmannin, who was so well received by the future Frederick I of Prussia that she could go unannounced into his cabinet.

There were also court Jews at all the petty German courts. Zacharias Seligmann (1694) worked in the service of the prince of Hesse-Homburg, and others served in the courts of the dukes of Mecklenburg. Others mentioned toward the end of the seventeenth century are Bendix and Ruben Goldschmidt of Homburg, Moses Israel Fürst, Michael Hinrichsen of Glückstadt, and his son, Reuben Hinrichsen. In the mid eighteenth century, the Jewish agent Wolf lived at the court of Frederick III of Mecklenburg-Strelitz.

The last actual court Jews were Israel Jacobson, court agent of Brunswick, and Wolf Breidenbach, factor to the Elector of Hesse, both of whom occupy honorable positions in the history of the Jews. Jacobsen (1768-1828) was a noted philanthropist who was influential in the establishment of Reform Judaism, while Breidenbach (d. 1829) was a champion of Jewish emancipation.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Mann, Vivian B., Richard I. Cohen, and Fritz Backhaus. From Court Jews to the Rothschilds: Art, Patronage, and Power: 1600-1800. Munich: Prestel, 1996. ISBN 9783791316246.

- Stern, Selma. The Court Jew: A Contribution to the History of the Period of Absolutism in Europe. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Books, 1985. ISBN 9780887380198.

- Vries, B.W. de. Of Mettle and Metal: From Court Jews to World-Wide Industrialists. Amsterdam: NEHA, 2000. ISBN 9789057420290.

- This article incorporates text from the 1901–1906 Jewish Encyclopedia, a publication now in the public domain.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.