Consumption tax

| Public finance |

|

| This article is part of the series: Finance and Taxation |

| Taxation |

|---|

| Ad valorem tax · Consumption tax Corporate tax · Excise Gift tax · Income tax Inheritance tax · Land value tax Luxury tax · Poll tax Property tax · Sales tax Tariff · Value added tax |

| Tax incidence |

| Flat tax · Progressive tax Regressive tax · Tax haven Tax rate |

| Economic policy |

| Monetary policy Central bank · Money supply |

| Fiscal policy Spending · Deficit · Debt |

| Trade policy Tariff · Trade agreement |

| Finance |

| Financial market Financial market participants Corporate · Personal Public · Banking · Regulation |

Taxing Income vs. Consumption

The basic difference between an income tax and a consumption tax is that a consumption tax only taxes money when it is spent. (Income taxes, by contrast, tax all the money you earn – including the amount you put away in your savings and the amount you get paid in interest.) Critics say the current system artificially increases the incentive to spend, while a consumption tax would encourage people to save and invest.

The Income Tax places taxes on business profit and on the employee's wages which the business withholds from the employee in trust for the government. The VAT ( i.e. a consumption tax ) taxes business profit and total employee wages directly. Collection of employee wage taxes, in the case of Income Tax, is called "withholding" and in the VAT it's a direct "labor tax" on the business.

EXAMPLE: With the Income Tax, a $100 wage may have $10 tax withheld by the employer leaving $90 for the employee. With the VAT, the employee would be paid $90 and the employer would be subject to a $10 labor tax. Other than how it's perceived, there appears to be no difference between a Value Added Tax and a truly flat, non-discriminatory Income Tax that's collected at the source of income.

Excise tax

Orthodox neoclassical economics has long maintained that, from the point of view of the taxed themselves, an income tax is "better than" an excise tax on a particular form of consumption, since, in addition to the total revenue extracted, which is assumed to be the same in both cases, the excise tax weights the levy heavily against a particular consumer good.

EXAMPLE: An excise tax, say, on whiskey or on movie admissions, will intrude directly on no one's life and income, but only into the sales of the movie theater or liquor store. It is quite feasible that, in evaluating the "superiority" or "inferiority" of different modes of taxation, even the most determined imbiber or moviegoer would cheerfully pay far higher prices for whiskey or movies than neoclassical economists contemplate, in order to avoid the long arm of the IRS ( NOTE [1] ).

But a new problem with excise tax appeared in the first decade of 21st century: a fast increasing price of gasoline and its excessive taxation. As gasoline is, in most developed countries, one of the necessities of life ( just like the foodstuff ) except that its price trend is several-fold steeper, one of the solution would, perhaps, be to nullify any excise tax on gasoline for “commuters” or introduce, for instance, a personal exemption.

Under this approach, which would differ substantially from a conventional value-added tax, workers would be considered to be "sellers" of labor services and would be subject to a value-added tax, but they could not take credits for value-added tax on their purchases of basic consumption goods, such as gasoline. Employers would be allowed a credit for the taxes "charged" by employees on their wages.

Argument for Consumption taxes

On the other side, the only coherent argument offered by advocates of consumption against income taxation is that of Irving Fisher, based on suggestions of John Stuart Mill. Fisher argued that, since the goal of all production is consumption, and since all capital goods are only way-stations on the way to consumption, the only genuine income is consumption spending. Based on consumption, rather than income, a national sales tax would not discriminate against saving the way the income tax does.

Accordingly, it may increase the level of private saving and generate a corresponding increase in capital formation and economic growth. A broad-based sales tax would almost certainly distort economic choices less than the income tax does. In contrast to the income tax, it would not discourage capital-intensive methods of production.

The conclusion is quickly drawn that therefore "...only consumption income, not what is generally called "income," should be subject to tax..." ( Rothbard, 1977, pp. 98–100.)

Market vs. People decision on savings

The market, in short, knows all about the productive power of savings for the future, and allocates its expenditures accordingly. Yet even though people know that savings will yield them more future consumption, why don't they save all their current income?

Clearly, because of their time preferences for present as against future consumption. These time preferences govern people's allocation between present and future. Every individual, given his money "income"---defined in conventional terms---and his value scales, will allocate that income in the most desired proportion between consumption and investment. Any other allocation of such income, any different proportions, would therefore satisfy his wants and desires to a lesser extent and lower his position on his value scale.

It is therefore incorrect to say that an income tax levies an extra burden on savings and investment; it penalizes an individual's entire standard of living, present and future. An income tax does not penalize saving per se any more than it penalizes consumption.

"......Having challenged the merits of the goal of taxing only consumption and freeing savings from taxation, we can now proceed to deny the very possibility of achieving that goal, i.e., we maintain that a consumption tax will devolve, willy-nilly, into a tax on income and therefore on savings as well. In short, that even if, for the sake of argument, we should want to tax only consumption and not income, we should not be able to do so...." ( Rothbard, 1977 ).

Numerical example

We can see it on a simple example. Let us take a, seemingly straightforward, tax plan that would exempt saving and tax only consumption. Let us take Mr. Jones, who earns an annual income of $100,000. His time preferences lead him to spend 90 percent of his income on consumption, and save-and-invest the other 10 percent. On this assumption, he will spend $90,000 a year on consumption, and save-and-invest the other $10,000.

Let us assume now that the government levies a 20 percent tax on Jones's income, and that his time-preference schedule remains the same. The ratio of his consumption to savings will still be 90:10, and so, after-tax income now being $80,000, his consumption spending will be $72,000 and his saving-investment $8,000 per year ( NOTE [2] ).

Suppose now that instead of an income tax, the government follows the Irving Fisher scheme and levies a 20 percent annual tax on Jones's consumption. Fisher maintained that such a tax would fall only on consumption, and not on Jones's savings. But this claim is incorrect, since Jones's entire savings-investment is based solely on the possibility of his future consumption, which will be taxed equally.

Since future consumption will be taxed, we assume, at the same rate as consumption at present, we cannot conclude that savings in the long run receives any tax exemption or special encouragement. There will therefore be no shift by Jones in favor of savings-and-investment due to a consumption tax ( NOTE [3]).

In sum, any payment of taxes to the government, whether they be consumption or income, necessarily reduces Jones's net income. Since his time preference schedule remains the same, Jones will therefore reduce his consumption and his savings proportionately. The consumption tax will be shifted by Jones until it becomes equivalent to a lower rate of tax on his own income.

If Jones still spends 90 percent of his net income on consumption, and 10 percent on savings-investment, his net income will be reduced by $15,000, instead of $20,000, and his consumption will now total $76,000, and his savings-investment $9,000. In other words, Jones's 20 percent consumption tax will become equivalent to a 15 percent tax on his income, and he will arrange his consumption-savings proportions accordingly (NOTE [4]).

Graphical example

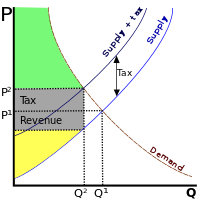

A VAT, like most taxes, distorts what would have happened without it. Because the price for someone rises, the quantity of goods traded decreases. Correspondingly, some people are worse off by more than the government is made better off by tax income . That is, more is lost due to supply and demand shifts than is gained in tax. This is known as a deadweight loss. The income lost by the economy is greater than the government's income; the tax is inefficient. The entire amount of the government's income (the tax revenue) may not be a deadweight drag, if the tax revenue is used for productive spending or has positive externalities - in other words, governments may do more than simply consume the tax income. While distortions occur, consumption taxes like VAT are often considered superior because they distort incentives to invest, save and work less than most other types of taxation - in other words, a VAT discourages consumption rather than production.

In the above diagram,

- Deadweight loss: the area of the triangle formed by the tax income box, the original supply curve, and the demand curve

- Government's tax income: the grey rectangle that says "tax"

- Total consumer surplus after the shift: the green area

- Total producer surplus after the shift: the yellow area

Notes

- [1] It is particularly poignant, on or near any April 15, to contemplate the dictum of Father Navarrete, that "...the only agreeable country is the one where no one is afraid of tax collectors..."( Chafuen, Christians for Freedom, p. 73.) Also see Murray N. Rothbard, "Review of A. Chafuen, Christians for Freedom: Late Scholastic Economics," International Philosophical Quarterly 28 (March 1988),pp. 112–14.

For a fuller treatment, and a discussion of who is being robbed by whom, see Murray N. Rothbard, Power and Market: Government and the Economy, 2nd ed. (Kansas City: Sheed Andrews & McMeel, 1977, pp. 120–21)

- [2] We set aside the fact that, at the lower amount of money assets left to him, Jones's time preference rate, given his time preference schedule, will be higher, so that his consumption will be higher, and his savings lower, than we have assumed.

- [3] In fact, per note [2], supra, there will be a shift in favor of consumption because a diminished amount of money will shift the taxpayer's time preference rate in the direction of consumption. Hence, paradoxically, a pure tax on consumption will and up taxing savings more than consumption( Rothbard, Power and Market, pp. 108–11.)

- [4] lf net income is defined as gross income minus amount paid in taxes, and for Jones, consumption is 90 percent of net income, a 20 percent consumption tax on $100,000 income will be tantamount to a 15 percent tax on this income( see: ibid. )

The basic formula for the net income is:

N = G / ( 1+ t.c ),

where G = gross income, t = the tax rate on consumption, and c, consumption as percent of net income, are givens of the problem, and N = G – T by definition, where T is the amount paid in consumption tax.