Difference between revisions of "Children's Crusade" - New World Encyclopedia

m |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (26 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Images OK}}{{submitted}}{{approved}}{{Paid}}{{copyedited}} |

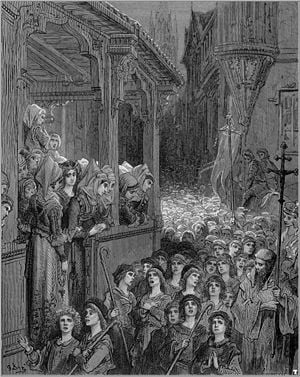

| + | [[Image:Gustave dore crusades the childrens crusade.jpg|thumb|300px|right|''The Children's Crusade'', by [[Gustave Doré]]]] | ||

| + | The '''Children's Crusade''' was a movement in 1212, initiated separately by two boys, each of whom claimed to have been inspired by a vision of [[Jesus]]. One of these boys mobilized followers to march to [[Jerusalem]] to convert [[Muslims]] in the [[Holy Land]] to [[Christianity]] and recover the [[True Cross]]. Whether comprised mainly of children or adults, they marched bravely over the mountains into [[Italy]], and some reached Rome, where their faith was praised by Pope [[Innocent III]]. Although the Pope did not encourage them to continue their march, stories of their faith may have stimulated future efforts by official [[Christendom]] to launch future Crusades. | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | The movement never reached the Holy Land. Many returned home or resumed previous lives as vagabonds, while others died on the journey, and still others were reportedly sold into[[ slavery]] or drowned at sea. Legends of both miracles and tragedies associated with the Children's Crusade abound, and the actual events continue to be a subject of debate among historians. | ||

| − | : | + | ==The long-standing view== |

| − | + | [[Image:Oriflamme.png|right|thumb|100px| Oriflamme banner reportedly carried by the Children's Crusade]] | |

| − | + | Although the common people held the same strong feelings of piety and religiousness that moved the nobles to take up the [[Cross]] in the thirteenth century, they did not have the finances, equipment, or military training to actually go on [[crusade]]. The repeated failures of earlier crusades frustrated those who held the hope to recover the [[True Cross]] and liberate [[Jerusalem]] from the "infidel" [[Muslims]]. This frustration led to unusual events in 1212 C.E.., in Europe. | |

| − | + | The traditional view of the Children's Crusade is that it was a mass movement in which a shepherd boy gathered thousands of children whom he proposed to lead to the conquest of [[Palestine]]. The movement then spread through [[France]] and [[Italy]], attended by [[miracle]]s, and was even blessed by the Pope [[Innocent III]], who said that the faith of these children "put us to shame." | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | The charismatic boy who led this Crusade was widely recognized among the populace as a living [[saint]]. Some 30,000 people were involved in the Crusade, only a few of them over 12 years of age. These innocent crusaders traveled southwards towards the [[Mediterranean Sea]], where they believed that the sea would part so they could march on to [[Jerusalem]], but this did not happen. Two merchants gave passage on seven boats to as many of the children as would fit. However, the children were either taken to [[Tunisia]] and sold into slavery, or died in a shipwreck on the island of [[San Pietro Island|San Pietro]] (off [[Sardinia]]) during a [[gale]]. In some accounts, they never even reached the sea before dying or giving up from starvation and exhaustion. | |

==Modern research== | ==Modern research== | ||

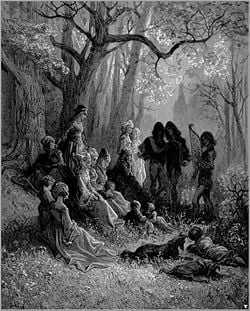

| − | + | [[Image:Gustave dore crusades troubadours singing the glories of the crusades.jpg|thumb|left|250px|Troubadours sing the glories of the crusades.]] | |

| + | Modern research has challenged the traditional view, asserting that the Children's Crusade was neither a true [[Crusade]] nor made up of an army of children. The Pope did not call for it, nor did he bless it. However, it did have an historical basis. Namely, it was an unsanctioned popular movement, whose beginnings are uncertain and whose ending is even harder to trace. Stories of the Crusades were the stuff of song and legend, and as storytellers and [[troubadour]]s embellished it, the legend of the Children's Crusade came to take on a life of its own. | ||

| + | |||

| + | There were actually two similar movements in 1212, one in [[France]] and the other in [[Germany]], which came to be merged together in the story of the Children's Crusade. Both were indeed inspired by children who had [[vision]]s. | ||

| − | In the first movement Nicholas, a shepherd from Germany, led a group across the [[Alps]] and into [[Italy]] in the early spring of 1212. | + | In the first movement, Nicholas, a ten-year-old shepherd from Germany, led a group across the [[Alps]] and into [[Italy]] in the early spring of 1212. Hundreds—and then thousands—of children, adolescents, women, the elderly, the poor, parish clergy, plus a number of petty thieves and prostitutes, joined him in his march south. He actually believed that God would part the waters of the [[Mediterranean]] and they would walk across to [[Jerusalem]] to convert the [[Muslims]] with love. The common folk praised the marchers as heroes as they passed through their towns and villages, but the educated clergy criticized them as deluded. In August, Nicholas' group reached [[Lombardy]] and other port cities. Nicholas himself arrived with a large group at [[Genoa]] on August 25. To their great disappointment the sea did not open for them, nor did it did allow them to walk across the waves. Here, many returned home, while others remained in Genoa. Some seem to have marched on to Rome, where the embarrassed Pope [[Innocent III]] indeed praised their zeal but released them from their supposed vows as crusaders and sent them home. The fate of Nicholas is unclear. Some sources say that he later joined the [[Fifth Crusade]], others reported that he died in Italy. |

| − | The second movement was led by a | + | The second movement was led by a 12 year old shepherd boy named [[Stephen de Cloyes]] near the village of [[Châteaudun]] in France, who claimed in June, 1212, that he bore a letter from [[Jesus]] for the French king. Stephen had met a [[pilgrim]] who asked for bread. When Stephen provided it, the beggar revealed himself to be Jesus and gave the boy a letter for the king. No one knows the content of the letter, but it is clear that the king, [[Phillip II]], did not want to lead another crusade at that time.<ref>Russell 1989.</ref> Nevertheless, Stephen attracted a large crowd and went to [[Saint-Denis, Seine-Saint-Denis|Saint-Denis]] where he was reportedly seen to work miracles. However, on the advice of clerics of the [[University of Paris]] and on the orders of Philip II, the crowd was sent home, and most of them went. None of the contemporary sources mentions this crowd heading to Jerusalem. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ===Wandering poor=== | |

| + | [[Image:Carlo Crivelli 012.jpg|thumb|left|125px|The Franciscans were one of several movements that appealed to "wandering poor."]] | ||

| + | Research suggests the participants in these movements were not primarily children. In the early 1200s, bands of wandering poor were commonplace throughout [[Europe]]. These were people displaced by [[economics|economic]] changes at the time which forced many poor [[peasant]]s in northern [[France]] and [[Germany]] to sell their land. These bands were referred to as ''pueri'' ([[Latin]] for "boys") in a condescending manner. Such groups were involved in various movements, from the heretical [[Waldensians]] to the theologically acceptable [[Franciscans]], to the so-called "children's crusaders." | ||

| − | + | Thus, in 1212, a young French ''puer'' named Stephen and a German ''puer'' named Nicholas separately began claiming that they each had visions of [[Jesus]]. This resulted in bands of roving poor being united into a religious movement which transformed this necessary wandering into a religious journey. The ''pueri'' marched, following the [[Christian cross|Cross]] and associating themselves with Jesus' biblical journey, the story of [[Moses]] crossing the [[Red Sea]], and also the aims of the [[Crusades]]. | |

| − | + | Thirty years later, chroniclers read the accounts of these processions and translated ''pueri'' as "children" without understanding the usage. Moreover, the movement did indeed seem to have been inspired by the visions and preaching of two young boys. However, the term "Children's Crusade" was born thirty years after the actual events. | |

==Historiography== | ==Historiography== | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | [[Peter Raedts]]'s (1977) analysis is considered the best source to date to show the many issues surrounding the Children's Crusade.<ref>ibid.</ref> According to Raedts, there are only about 50 sources from the period that talk about the Children's Crusade, ranging from a few sentences to half a page. Raedts categorizes the sources into three types depending on when they were written: | |

| − | + | *contemporary sources written by 1220 | |

| + | *sources written between 1220 and 1250 when memories of the events may have been first-hand | ||

| + | *sources written after 1250 by authors who received their information second or third generation | ||

| + | Raedts does not consider the sources after 1250 to be authoritative, and of those before 1250, he considers only about 20 to be authoritative. It is only in the later non-authoritative narratives that a "Children's Crusade" is implied by such authors as [[Vincent of Beauvais|Beauvais]], [[Roger Bacon]], [[Thomas of Cantimpré]], [[Matthew Paris]], and others. | ||

| − | [[P. Alphandery]] | + | Prior to Raedts there had only been a few academic publications researching the Children's Crusade. Most of them uncritically accepted the validity of relatively late sources. The earliest were by [[G. de Janssens]] (1891), a Frenchman, and [[R. Röhricht]] (1876), a German. They did analyze the sources, but did not apply this analysis the story itself. German psychiatrist [[J. F. C. Hecker]] (1865) did give an original interpretation of the Crusade, regarding is as the result of "diseased religious emotionalism."<ref>Raedts 1977.</ref> American medievalist [[D. C. Munro]] (1913-14) was the first to provide a sober account of the Children's Crusade without legends.<ref>Munro, 19: 516-24. (1913-14)</ref> Later, [[J. E. Hansbery]] (1938-9) published a correction of Munro's work claiming the Children's Crusade to have been an actual historical Crusade, but it has since been repudiated as being itself based on an unreliable source.<ref>Raedts 1977.</ref> [[P. Alphandery]] first published his ideas about the Children's Crusade a 1916 article, which was expanded to book form in 1959. He considered the event to be an expression of the medieval "Cult of the Innocents," as a sort of sacrificial rite in which children gave themselves up for the good of [[Christendom]]. His sources have also been criticized as biased.<ref>P. Alphandery, 1995.</ref> [[Adolf Waas]] (1956) saw the events as a manifestation of chivalric piety and as a protest against the glorification of the holy war. [[H. E. Mayer]] (1960) further developed Alphandery's ideas of the Innocents, saying children were thought to be the chosen people of God because they were the poorest, recognizing the cult of poverty he said that "the Children's Crusade marked both the triumph and the failure of the idea of poverty." |

| − | [[ | + | [[Norman Cohn]] (1971) saw it as a millennial movement in which the poor tried to escape the misery of their everyday lives. He and Giovanni Miccoli (1961) both noted that the contemporary sources did not portray the participants as children. It was this recognition that undermined earlier interpretations. <ref>Cohn 1993.</ref> |

| − | + | ===Other accounts=== | |

| + | Beyond the analytical studies, interpretations and theories about the Children's Crusades have been put forth. | ||

| − | [[ | + | [[Norman Zacour]] in the survey, ''A History of the Crusades'' (1962), generally follows Munro's conclusions, and adds that there was a psychological instability of the age, concluding that the Children's Crusade "remains one of a series of social explosions, through which medieval men and women—and children, too—found release." |

| − | [[ | + | [[Donald Spoto]], in a book about [[Saint Francis]], said monks were motivated to call the participants "children," and not wandering poor, because being poor was considered pious and the Church was embarrassed by its wealth in contrast to the poor. This, according to Spoto, began a literary tradition from which the popular legend of children originated. This idea follows closely with H. E. Mayer. |

| − | + | Church historian [[Steven Runciman]] gives an account of the Children's Crusade in his ''A History of the Crusades,'' in which he cites Munro's research. Raedts, however, criticizes Runciman's account misunderstanding Munro's basic conclusion. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[Steven Runciman]] gives an account of the Children's Crusade in his ''A History of the Crusades | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==In the arts== | ==In the arts== | ||

| − | + | The Children's Crusade has inspired numerous works of twentieth century and contemporary music, and literature including: | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

* ''La Croisade des Enfants'' (1902), a seldom-performed [[oratorio]] by [[Gabriel Pierné]]'s, featuring a children's chorus, is based on the events of the Children's Crusade. | * ''La Croisade des Enfants'' (1902), a seldom-performed [[oratorio]] by [[Gabriel Pierné]]'s, featuring a children's chorus, is based on the events of the Children's Crusade. | ||

* ''The Children's Crusade'' (circa 1950), children's historical novel by [[Henry Treece]] based on the traditional view. | * ''The Children's Crusade'' (circa 1950), children's historical novel by [[Henry Treece]] based on the traditional view. | ||

* ''The Death of the Bishop of Brindisi'' (1963), opera by [[Gian-Carlo Menotti]], describes a dying bishop's guilt-ridden recollection of the Children's Crusade, during which he questions the purpose and limitations of his own power. | * ''The Death of the Bishop of Brindisi'' (1963), opera by [[Gian-Carlo Menotti]], describes a dying bishop's guilt-ridden recollection of the Children's Crusade, during which he questions the purpose and limitations of his own power. | ||

* ''[[Slaughterhouse-Five]]'' (1969), a novel by [[Kurt Vonnegut]], references this event and uses it as an alternate title. | * ''[[Slaughterhouse-Five]]'' (1969), a novel by [[Kurt Vonnegut]], references this event and uses it as an alternate title. | ||

| − | * ''[[Crusade in Jeans]]'' (Dutch ''Kruistocht in spijkerbroek''), is a 1973 novel by Dutch author [[Thea Beckman]] and a [[Crusade in Jeans (film)|2006 film adaptation]] about the Children's Crusade through the eyes of a time | + | * ''[[Crusade in Jeans]]'' (Dutch ''Kruistocht in spijkerbroek''), is a 1973 novel by Dutch author [[Thea Beckman]] and a [[Crusade in Jeans (film)|2006 film adaptation]] about the Children's Crusade through the eyes of a time traveler. |

* ''[[An Army of Children]]'' (1978), a novel by [[Evan Rhodes]] that tells the story of two boys partaking in the Children's Crusade. | * ''[[An Army of Children]]'' (1978), a novel by [[Evan Rhodes]] that tells the story of two boys partaking in the Children's Crusade. | ||

* "[[The Dream of the Blue Turtles|Children's Crusade]]" (1985), is a song by [[Sting (singer)|Sting]] that juxtaposes the medieval Children's Crusade with the deaths of [[England|English]] [[soldier]]s in [[World War I]] and the lives ruined by [[heroin]] [[addiction]]. | * "[[The Dream of the Blue Turtles|Children's Crusade]]" (1985), is a song by [[Sting (singer)|Sting]] that juxtaposes the medieval Children's Crusade with the deaths of [[England|English]] [[soldier]]s in [[World War I]] and the lives ruined by [[heroin]] [[addiction]]. | ||

| Line 67: | Line 65: | ||

* ''The Crusade of Innocents'' (2006), novel by [[David George]], suggests that the Children's Crusade may have been affected by the concurrent crusade against the Cathars in Southern France, and how the two could have met. | * ''The Crusade of Innocents'' (2006), novel by [[David George]], suggests that the Children's Crusade may have been affected by the concurrent crusade against the Cathars in Southern France, and how the two could have met. | ||

* [[Sylvia (novel)|''Sylvia'']] (2006), novel by [[Bryce Courtenay]], story loosely based around the Children's Crusade. | * [[Sylvia (novel)|''Sylvia'']] (2006), novel by [[Bryce Courtenay]], story loosely based around the Children's Crusade. | ||

| − | + | * "Sea and Sunset," short story by [[Mishima Yukio]]. | |

| − | * "Sea and Sunset" | + | * ''Fleeing the Children's Crusade'' (2005), novel by [[Travis Godbold]], tells the story of a twentieth century Children's Crusade, Nazi Germany's fight against Soviet Bolshevism, and a teenage soldier's experiences in the Waffen SS at the end of World War II. |

| − | * ''Fleeing the Children's Crusade | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| − | |||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| + | * Alphandery, P. ''La Chrétienté et l'idée de croisade''. (French). A. Michel publ., 1995. ISBN 978-2226076298 | ||

| + | * Boswell, John. ''The Kindness of Strangers: The Abandonment of Children in Western Europe from Late Antiquity to the Renaissance''. University of Chicago Press, 1998. ISBN 978-0226067124 | ||

* Brundage, James trans. (from "Chronica Regiae Coloniensis Continuatio prima, s.a. 1213, MGH SS XXIV 17-18,") ''The Crusades: A Documentary History''. Milwaukee, WI: Marquette University Press, 1962. | * Brundage, James trans. (from "Chronica Regiae Coloniensis Continuatio prima, s.a. 1213, MGH SS XXIV 17-18,") ''The Crusades: A Documentary History''. Milwaukee, WI: Marquette University Press, 1962. | ||

| − | * Cohn, N. ''The | + | * Cohn, N. ''The Pursuit of the Millennium''. Pimlico, 1993. ISBN 978-0712656641 |

| − | * Raedts, Peter. "The Children's Crusade of 1212," | + | * Giles, J.A., trans. ''Matthew Paris's English History: From 1235 to 1273.'' Vol. II. Henry G. Hohn, 1853. |

| + | * Hazard, Harry W. and Norman P. Zacour. ''A History of the Crusades: The Impact of the Crusades on Europe (History of the Crusades)''. University of Wisconsin Press, 1990. ISBN 978-0299107406 | ||

| + | * ''History's Mysteries: The Children's Crusade''. A & E Home Video. | ||

| + | * Munro, D.C. "The Children's Crusade." ''American Historical Review,'' 19:516-24, 1913-14. | ||

| + | * Paris, Matthew. ''Illustrated Chronicles of Matthew Paris ''. Sutton Publishers, Ltd. 1987. ISBN 978-0862993047 | ||

| + | * Raedts, Peter. "The Children's Crusade of 1212," ''[[Journal of Medieval History]]'', vol. 3 1977. | ||

* Runciman, Stephen. ''A History of the Crusades''. 1951. [http://www.historyguide.org/ancient/children.html The Children's Crusade]. ''www.historyguide.org''. Retrieved August 4, 2007. | * Runciman, Stephen. ''A History of the Crusades''. 1951. [http://www.historyguide.org/ancient/children.html The Children's Crusade]. ''www.historyguide.org''. Retrieved August 4, 2007. | ||

| − | * Russell, Frederick. "Children's Crusade," in ''Dictionary of the Middle Ages'' | + | * Russell, Frederick. "Children's Crusade," in ''Dictionary of the Middle Ages.'' 1989. ISBN 0-684-17024-8 |

| − | * | + | * Zacour, Norman. ''Introduction To Medieval Institutions.'' St. Martins Press, 1900. |

| − | + | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{Credit|132781832}} | {{Credit|132781832}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:History]] | ||

Latest revision as of 15:33, 10 December 2023

The Children's Crusade was a movement in 1212, initiated separately by two boys, each of whom claimed to have been inspired by a vision of Jesus. One of these boys mobilized followers to march to Jerusalem to convert Muslims in the Holy Land to Christianity and recover the True Cross. Whether comprised mainly of children or adults, they marched bravely over the mountains into Italy, and some reached Rome, where their faith was praised by Pope Innocent III. Although the Pope did not encourage them to continue their march, stories of their faith may have stimulated future efforts by official Christendom to launch future Crusades.

The movement never reached the Holy Land. Many returned home or resumed previous lives as vagabonds, while others died on the journey, and still others were reportedly sold intoslavery or drowned at sea. Legends of both miracles and tragedies associated with the Children's Crusade abound, and the actual events continue to be a subject of debate among historians.

The long-standing view

Although the common people held the same strong feelings of piety and religiousness that moved the nobles to take up the Cross in the thirteenth century, they did not have the finances, equipment, or military training to actually go on crusade. The repeated failures of earlier crusades frustrated those who held the hope to recover the True Cross and liberate Jerusalem from the "infidel" Muslims. This frustration led to unusual events in 1212 C.E., in Europe.

The traditional view of the Children's Crusade is that it was a mass movement in which a shepherd boy gathered thousands of children whom he proposed to lead to the conquest of Palestine. The movement then spread through France and Italy, attended by miracles, and was even blessed by the Pope Innocent III, who said that the faith of these children "put us to shame."

The charismatic boy who led this Crusade was widely recognized among the populace as a living saint. Some 30,000 people were involved in the Crusade, only a few of them over 12 years of age. These innocent crusaders traveled southwards towards the Mediterranean Sea, where they believed that the sea would part so they could march on to Jerusalem, but this did not happen. Two merchants gave passage on seven boats to as many of the children as would fit. However, the children were either taken to Tunisia and sold into slavery, or died in a shipwreck on the island of San Pietro (off Sardinia) during a gale. In some accounts, they never even reached the sea before dying or giving up from starvation and exhaustion.

Modern research

Modern research has challenged the traditional view, asserting that the Children's Crusade was neither a true Crusade nor made up of an army of children. The Pope did not call for it, nor did he bless it. However, it did have an historical basis. Namely, it was an unsanctioned popular movement, whose beginnings are uncertain and whose ending is even harder to trace. Stories of the Crusades were the stuff of song and legend, and as storytellers and troubadours embellished it, the legend of the Children's Crusade came to take on a life of its own.

There were actually two similar movements in 1212, one in France and the other in Germany, which came to be merged together in the story of the Children's Crusade. Both were indeed inspired by children who had visions.

In the first movement, Nicholas, a ten-year-old shepherd from Germany, led a group across the Alps and into Italy in the early spring of 1212. Hundreds—and then thousands—of children, adolescents, women, the elderly, the poor, parish clergy, plus a number of petty thieves and prostitutes, joined him in his march south. He actually believed that God would part the waters of the Mediterranean and they would walk across to Jerusalem to convert the Muslims with love. The common folk praised the marchers as heroes as they passed through their towns and villages, but the educated clergy criticized them as deluded. In August, Nicholas' group reached Lombardy and other port cities. Nicholas himself arrived with a large group at Genoa on August 25. To their great disappointment the sea did not open for them, nor did it did allow them to walk across the waves. Here, many returned home, while others remained in Genoa. Some seem to have marched on to Rome, where the embarrassed Pope Innocent III indeed praised their zeal but released them from their supposed vows as crusaders and sent them home. The fate of Nicholas is unclear. Some sources say that he later joined the Fifth Crusade, others reported that he died in Italy.

The second movement was led by a 12 year old shepherd boy named Stephen de Cloyes near the village of Châteaudun in France, who claimed in June, 1212, that he bore a letter from Jesus for the French king. Stephen had met a pilgrim who asked for bread. When Stephen provided it, the beggar revealed himself to be Jesus and gave the boy a letter for the king. No one knows the content of the letter, but it is clear that the king, Phillip II, did not want to lead another crusade at that time.[1] Nevertheless, Stephen attracted a large crowd and went to Saint-Denis where he was reportedly seen to work miracles. However, on the advice of clerics of the University of Paris and on the orders of Philip II, the crowd was sent home, and most of them went. None of the contemporary sources mentions this crowd heading to Jerusalem.

Wandering poor

Research suggests the participants in these movements were not primarily children. In the early 1200s, bands of wandering poor were commonplace throughout Europe. These were people displaced by economic changes at the time which forced many poor peasants in northern France and Germany to sell their land. These bands were referred to as pueri (Latin for "boys") in a condescending manner. Such groups were involved in various movements, from the heretical Waldensians to the theologically acceptable Franciscans, to the so-called "children's crusaders."

Thus, in 1212, a young French puer named Stephen and a German puer named Nicholas separately began claiming that they each had visions of Jesus. This resulted in bands of roving poor being united into a religious movement which transformed this necessary wandering into a religious journey. The pueri marched, following the Cross and associating themselves with Jesus' biblical journey, the story of Moses crossing the Red Sea, and also the aims of the Crusades.

Thirty years later, chroniclers read the accounts of these processions and translated pueri as "children" without understanding the usage. Moreover, the movement did indeed seem to have been inspired by the visions and preaching of two young boys. However, the term "Children's Crusade" was born thirty years after the actual events.

Historiography

Peter Raedts's (1977) analysis is considered the best source to date to show the many issues surrounding the Children's Crusade.[2] According to Raedts, there are only about 50 sources from the period that talk about the Children's Crusade, ranging from a few sentences to half a page. Raedts categorizes the sources into three types depending on when they were written:

- contemporary sources written by 1220

- sources written between 1220 and 1250 when memories of the events may have been first-hand

- sources written after 1250 by authors who received their information second or third generation

Raedts does not consider the sources after 1250 to be authoritative, and of those before 1250, he considers only about 20 to be authoritative. It is only in the later non-authoritative narratives that a "Children's Crusade" is implied by such authors as Beauvais, Roger Bacon, Thomas of Cantimpré, Matthew Paris, and others.

Prior to Raedts there had only been a few academic publications researching the Children's Crusade. Most of them uncritically accepted the validity of relatively late sources. The earliest were by G. de Janssens (1891), a Frenchman, and R. Röhricht (1876), a German. They did analyze the sources, but did not apply this analysis the story itself. German psychiatrist J. F. C. Hecker (1865) did give an original interpretation of the Crusade, regarding is as the result of "diseased religious emotionalism."[3] American medievalist D. C. Munro (1913-14) was the first to provide a sober account of the Children's Crusade without legends.[4] Later, J. E. Hansbery (1938-9) published a correction of Munro's work claiming the Children's Crusade to have been an actual historical Crusade, but it has since been repudiated as being itself based on an unreliable source.[5] P. Alphandery first published his ideas about the Children's Crusade a 1916 article, which was expanded to book form in 1959. He considered the event to be an expression of the medieval "Cult of the Innocents," as a sort of sacrificial rite in which children gave themselves up for the good of Christendom. His sources have also been criticized as biased.[6] Adolf Waas (1956) saw the events as a manifestation of chivalric piety and as a protest against the glorification of the holy war. H. E. Mayer (1960) further developed Alphandery's ideas of the Innocents, saying children were thought to be the chosen people of God because they were the poorest, recognizing the cult of poverty he said that "the Children's Crusade marked both the triumph and the failure of the idea of poverty."

Norman Cohn (1971) saw it as a millennial movement in which the poor tried to escape the misery of their everyday lives. He and Giovanni Miccoli (1961) both noted that the contemporary sources did not portray the participants as children. It was this recognition that undermined earlier interpretations. [7]

Other accounts

Beyond the analytical studies, interpretations and theories about the Children's Crusades have been put forth.

Norman Zacour in the survey, A History of the Crusades (1962), generally follows Munro's conclusions, and adds that there was a psychological instability of the age, concluding that the Children's Crusade "remains one of a series of social explosions, through which medieval men and women—and children, too—found release."

Donald Spoto, in a book about Saint Francis, said monks were motivated to call the participants "children," and not wandering poor, because being poor was considered pious and the Church was embarrassed by its wealth in contrast to the poor. This, according to Spoto, began a literary tradition from which the popular legend of children originated. This idea follows closely with H. E. Mayer.

Church historian Steven Runciman gives an account of the Children's Crusade in his A History of the Crusades, in which he cites Munro's research. Raedts, however, criticizes Runciman's account misunderstanding Munro's basic conclusion.

In the arts

The Children's Crusade has inspired numerous works of twentieth century and contemporary music, and literature including:

- La Croisade des Enfants (1902), a seldom-performed oratorio by Gabriel Pierné's, featuring a children's chorus, is based on the events of the Children's Crusade.

- The Children's Crusade (circa 1950), children's historical novel by Henry Treece based on the traditional view.

- The Death of the Bishop of Brindisi (1963), opera by Gian-Carlo Menotti, describes a dying bishop's guilt-ridden recollection of the Children's Crusade, during which he questions the purpose and limitations of his own power.

- Slaughterhouse-Five (1969), a novel by Kurt Vonnegut, references this event and uses it as an alternate title.

- Crusade in Jeans (Dutch Kruistocht in spijkerbroek), is a 1973 novel by Dutch author Thea Beckman and a 2006 film adaptation about the Children's Crusade through the eyes of a time traveler.

- An Army of Children (1978), a novel by Evan Rhodes that tells the story of two boys partaking in the Children's Crusade.

- "Children's Crusade" (1985), is a song by Sting that juxtaposes the medieval Children's Crusade with the deaths of English soldiers in World War I and the lives ruined by heroin addiction.

- Lionheart (1987), a little known historical/fantasy film, loosely based on the stories of the Children's Crusade.

- The Children's Crusade (1993)), comic series by Neil Gaiman.

- The Crusade of Innocents (2006), novel by David George, suggests that the Children's Crusade may have been affected by the concurrent crusade against the Cathars in Southern France, and how the two could have met.

- Sylvia (2006), novel by Bryce Courtenay, story loosely based around the Children's Crusade.

- "Sea and Sunset," short story by Mishima Yukio.

- Fleeing the Children's Crusade (2005), novel by Travis Godbold, tells the story of a twentieth century Children's Crusade, Nazi Germany's fight against Soviet Bolshevism, and a teenage soldier's experiences in the Waffen SS at the end of World War II.

Notes

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Alphandery, P. La Chrétienté et l'idée de croisade. (French). A. Michel publ., 1995. ISBN 978-2226076298

- Boswell, John. The Kindness of Strangers: The Abandonment of Children in Western Europe from Late Antiquity to the Renaissance. University of Chicago Press, 1998. ISBN 978-0226067124

- Brundage, James trans. (from "Chronica Regiae Coloniensis Continuatio prima, s.a. 1213, MGH SS XXIV 17-18,") The Crusades: A Documentary History. Milwaukee, WI: Marquette University Press, 1962.

- Cohn, N. The Pursuit of the Millennium. Pimlico, 1993. ISBN 978-0712656641

- Giles, J.A., trans. Matthew Paris's English History: From 1235 to 1273. Vol. II. Henry G. Hohn, 1853.

- Hazard, Harry W. and Norman P. Zacour. A History of the Crusades: The Impact of the Crusades on Europe (History of the Crusades). University of Wisconsin Press, 1990. ISBN 978-0299107406

- History's Mysteries: The Children's Crusade. A & E Home Video.

- Munro, D.C. "The Children's Crusade." American Historical Review, 19:516-24, 1913-14.

- Paris, Matthew. Illustrated Chronicles of Matthew Paris . Sutton Publishers, Ltd. 1987. ISBN 978-0862993047

- Raedts, Peter. "The Children's Crusade of 1212," Journal of Medieval History, vol. 3 1977.

- Runciman, Stephen. A History of the Crusades. 1951. The Children's Crusade. www.historyguide.org. Retrieved August 4, 2007.

- Russell, Frederick. "Children's Crusade," in Dictionary of the Middle Ages. 1989. ISBN 0-684-17024-8

- Zacour, Norman. Introduction To Medieval Institutions. St. Martins Press, 1900.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.