Book of Hours

The Books of Hours (Latin: Horae; English: Primer)[1] represented a class of devotional manuals popular among medieval Catholic laity. Though their contents were relatively variable, each Book typically contained a detailed Calendar of Saints, a series of Marian devotions (modeled on the Canonical Hours followed by monastic orders), and a catalog of other prayers. These various devotional passages were typically recorded in Latin, with the inclusion of any vernacular tongue being a relative rarity.

As these texts were often the central objects in a lay follower's personal piety, they were highly prized possessions. Among the upper classes, this meant that they were often sumptuously decorated with jewels, gold-leaf, hand-painted illustrations, and (less frequently) with portraits of their owners. Even the less affluent would often save up their minimal earnings in order to purchase their own copies of the texts, though necessity often forced them to opt for inexpensive, block-printed editions. The ubiquity of these Books of Hours among fourteenth, fifteenth and sixteenth century Christians has made them the most common type of surviving medieval illuminated manuscript.[2]

History

In the ninth and tenth centuries of the Common Era, monastic piety underwent a number of gradual changes, especially in the area of liturgical expression. Most notably, various devotionally-motivated renunciants championed the modification of the Divine Office (also known as the Canonical Hours), a well-established system of prayers and readings scheduled for various periods during a typical day. Specifically, these reformers urged their co-religionists to build upon the existing calendar by including both a memorial vigil and various Marian prayers. Both of these modifications, while initially localized to the congregations of their supporters, eventually became the liturgical status quo, leading to the modification of existing prayer manuals and devotional calendars:

- the Primer [or, more properly, its monastic antecedent] was constituted out of certain devotional accretions to the Divine Office itself which were invented first by the piety of individuals for the use of monks in their monasteries, but which gradually spread and came to be regarded as an obligatory supplement to the office of the day. Of these accretions the Fifteen Psalms and the Seven Psalms were the earliest in point of time to establish themselves generally and permanently. Their adoption as part of the daily round of monastic devotion was probably largely due to the influence of St. Benedict of Aniane at the beginning of the ninth century. The "Vigiliae Mortuorum", or Office for the Dead, was the next accretion to be generally received. Of the cursus or Little Office of the Blessed Virgin we hear nothing until the time of Bernerius of Verdun (c. 960) and of St. Udalric of Augsburg (c. 97l); but this form of devotion to Our Lady spread rapidly. ... In these provision was probably made only for the private recitation of the Office of the Blessed Virgin, but after the ardent encouragement given to this form of devotion by St. Peter Damian in the middle of the tenth century many monastic orders adopted it or retained it in preference to some other devotional offices, e.g., those of All Saints and of the Blessed Trinity, which had found favour a little earlier.[3]

With this gradual modification of monastic religious practice came an eventual adoption by the laity, who viewed their ecclesiastical counterparts as spiritual exemplars par excellence. This ritualized means of dedicating one's life to God soon swept into the mainstream in upper class Europe, with a popularity that could be attributed to a number of related factors, including the lay instruction of the friars, the religious reforms of the Fourth Lateran Council, the idle hours experienced by the aristocracy (especially affluent noblewomen), and the mortal fear inculcated by the Black Death (and other epidemics). Duffy's instructive History Today article cogently summarizes this development:

- By the early thirteenth century, England and the whole of Western Europe was in the full flood of the great expansion of religious provision for lay people associated with the Fourth Lateran Council (1215), and the popular Christianity of the friars. Devout lay people, especially among the leisured and well-heeled, and perhaps especially among wealthy women, were responding to the heightened mood of religious seriousness. Growing numbers were interested in the pursuit of a serious interior religious life, enough of them literate to create a market for religious books designed to cater for their needs. Books of Hours were the most important manifestation of this expanding devotional literacy.[4]

Given the exorbitant costs associated with hand-copied texts, this devotional path (and the prayer texts undergirding it) were originally only available to the royalty, the nobility, and the rich who could afford to purchase a personal Book of Hours. This cachet, based as it was on both spiritual and pecuniary exaltation, caused these texts to be revered as personal treasures, though it was eventually lost with the advent of modern printing technology. Indeed, the proprietary access to sanctity that was initially promised by the Book of Hours was abruptly quashed in the 15th century, when advances in printing technology made the books more affordable, sometimes allowing even commoners and servants to purchase one of the printed, unbound versions. At the same time, this general availability, coupled with the religious ferment that enveloped Europe for the next several centuries, combined to remove the Book of Hours from its place of primacy in personal spirituality, allowing it to gradually be eclipsed by various other prayer books (both Catholic and Protestant).[5]

The influence of these texts can still be seen, albeit obliquely, in the etymology and definition of the word "primer." Though today used to depict any variety of instructional text, it was originally used only to describe Books of Hours. This educational connotation arose due to the fact that the majority of literate individuals during the Middle Ages learned to read by following the daily devotions required by the calendrical text.[6]

Contents

As noted above the Book of Hours was originally a portable version of the Divine Office—a calendrical index of days, times, and the appropriate Biblical texts (typically Psalms) to be recited for each liturgical hour. With the passage of time (and the evolution of monastic worship), these contents were updated with that were to be recited at would list the appropriate texts for each liturgical hour of the day. However, over time, other references were often added, especially calendars of the religious and secular year along with the prayers and masses required for certain holy days.

The typical medieval manuscript called a book of hours is an abbreviated breviary, the book containing the liturgy recited in cloistered monasteries. The books of hours were composed for the lay people who wished to incorporate elements of monasticism into their devotional life. Reciting the hours typically centered upon the recitation or singing of a number of psalms, accompanied by set prayers. A typical book of hours contained:

- The Little Office of the Blessed Virgin Mary, which included the fifteen Psalms of Degrees;

- The Office for the Dead, which included the seven Penitential Psalms;

- The Litany of Saints

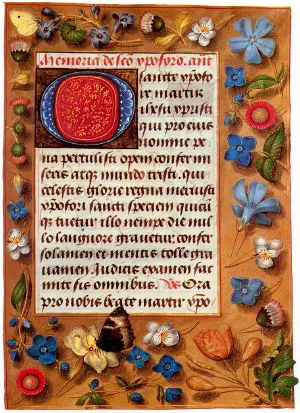

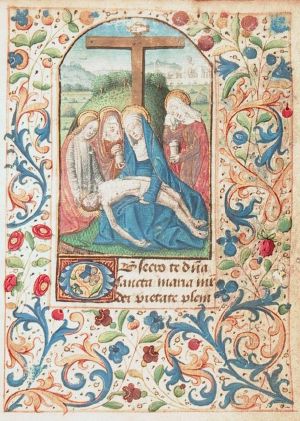

Most books of hours began with these basic contents, and expanded them with a variety of prayers and devotions. The Marian prayers Obsecro te ("I beseech thee") and O Intemerata ("O undefiled one") were frequently added, as were devotions for use at Mass, and meditations on the Passion of Christ.

Owners often added their own notes.<use as segue>

Decorations

<fit in> In turn, this often led to a personalization of these texts with the inclusion of decorations, painted portraits, and prayers specifically composed for their owners or adapted to their tastes or genders. To this end, one common method used by scribes was to ink their customer's name into any suitable prayers, which turned the finished tome into a concrete relic of their piety.[7] < >

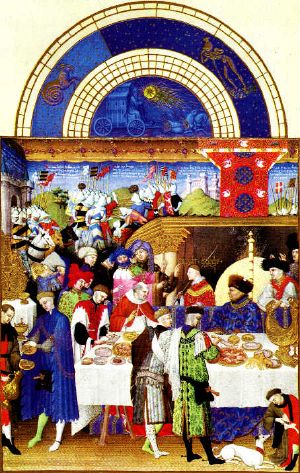

As many books of hours are richly illuminated, they form an important record of life in the 15th and 16th centuries as well as the iconography of medieval Christianity. Some of them were also decorated with jewelled covers, portraits, heraldic emblems, numerous illustrations, textual illuminations and marginal decorations. Many were bound as girdle books for easy carrying. Many, like the Talbot Hours of John Talbot, 1st Earl of Shrewsbury, include a portrait of the owner, and in this case his wife, kneeling in adoration of the Virgin and Child. Large miniature cycles often covered the Labours of the Months, decorating the calendar, the Life of the Virgin in eight scenes decorating the Hours of the Virgin, which were sometimes decorated with the Passion of Christ instead.

The amount of money the books of hours represented made them also important status symbols that the wealthy wanted to have whether they were pious or not. Wealthy people also sometimes competed trying to outdo each other with decorations of the books they commissioned. The books were also often passed along as gifts to favoured children, friends and servants and even as signs of dynastic allegiances. A mother could pass her book on to her eldest daughter, and the same book could pass along in the same family for centuries. Various queens gave books to their favoured ladies in waiting.

Long-lived books of hours could also be modified for their new owner. After defeating Richard III, Henry VII gave Richard's book of hours to his mother, and she modified it to include her name. Many surviving books have numerous handwritten annotations, personal additions and marginal notes but some new owners also commissioned new craftsmen to include more illustrations or scripts. Sir Thomas Lewkenor of Trotton hired an illustrator to add details to what is now known as the Lewkenor Hours.

The pages of books with a less glorious fate could have been just used for notes and scrap paper. Flyleaves of many surviving books include notes of household accounting or records of births and deaths. Some owners had also collected autographs and remembrances of visitors.

Towards the end of the 15th century, printers produced books of hours with woodcut illustrations. Stationers could mass-produce manuscript books on vellum with only plain artwork and later "personalize" them with equally mass-produced sets of illustrations from local printers.

Sample books of hours

One of the most famous books of hours, and one of the most richly illuminated medieval manuscripts, is the Très Riches Heures painted sometime between 1412 and 1416 in France for John, Duke of Berry.

The De Brailes Hours was made around 1240. It is the earliest surviving English book of hours and includes four portraits of its first owner.

The Rothschild Prayerbook

The Rothschild Prayerbook, use of Rome, was made c. 1505 and is only three and a half inches thick. Louis Nathaniel von Rothschild owned it but Nazis confiscated the medieval Rothschild Book of Hours immediately after the March 1938 German annexation of Austria from members of the Viennese branch of the Mayer Amschel Rothschild family. Through the efforts of Bettina Looram-Rothschild, the niece and heir of the owner, the government of Austria returned the book and other works of art to her in 1999. It was sold for Ms Looram-Rothschild by Christie's auction house of London on July 8, 1999 for £8,580,000 ($13,400,000), a world auction record price for an illuminated manuscript.

The Connolly Book of Hours

The Connolly Book of Hours, was produced during the fifteenth century and is an excellent example of a manuscript Book of Hours produced for a non-aristocratic patron. It was the subject of a 1999 volume by Timothy M. Sullivan, et al, that documented and contextualized all the illuminated leaves in the book.

See also

- Canonical hours

- Horologion

Notes

- ↑ The English term ("primer") is attested to in the Oxford English Dictionary, which states: "The medieval Primarium or Primer was mainly a copy, or (in English) a translation of different parts of the Breviary and Manual. In the 14th and 15th centuries, in its simplest form, it contained the Hours of the Blessed Virgin (the essential element), the 7 Penitential and 15 Gradual Psalms, the Litany, the Office for the Dead (Placebo and Dirige), and the Commendations; to which however various additions were often made. Early 16th cent. printed editions of these medieval works were freq. given the name Prymer on the title page. ... After 1600 the word gradually lost these religious meanings, although in 17th-cent. England it continued to be used to denote a Roman Catholic prayer book translated into the vernacular" (2007). See also: the entry in the Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ↑ "Book of Hours" The Oxford Dictionary of Art. Retrieved 18 October 2007. [1].

- ↑ Thurston (1911). The particulars of these accretions will be discussed below. See also Duffy (2006), 12-13.

- ↑ Duffy (2006), 13-14.

- ↑ Thurston, ""Prayer Books" and "The Primer" (1911). Duffy (2005), 211-213.

- ↑ See the "Primer" entries in the Oxford English Dictionary and the Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ↑ Duffy (2006), 16.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Chilvers, Ian (ed). The Oxford Dictionary of Art. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004. ISBN 0198604769.

- Duffy, Eamon. The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England 1400-1580. New Haven, CT: Yale, 1992. Second Printing, 2005. ISBN 0-300-06076-9

- Duffy, Eamon. "A Very Personal Possession." History Today 56:11 (November 2006). 12-18.

- Thurston, Herbert. "Prayer Books." Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1911.

- Thurston, Herbert. "The Primer." Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1911.

- Toke, Leslie A. St. L. "Little Office of Our Lady." Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910.

External links

All links retrieved October 17, 2007

- A Hypertext Book of Hours; full texts and translation

- A catalog of images from various illuminated manuscripts

- Late Medieval and Renaissance Illuminated Manuscripts - Books of Hours 1400-1530 - An excellent guide to the Book of Hours as a literary and devotional artifact. Featuring original Latin texts and high-resolution photographs of many books.

- Online Versions of Individual Manuscripts

- Book of Hours (Ms. Library of Congress. Rosenwald ms. 10) From the Rare Book and Special Collections Division of the Library of Congress.The same in pdf format.

- MS Richardson 7. Heures de Nôtre Dame at Houghton Library, Harvard University.

- A Masterpiece Reconstructed: The Hours of Louis XII. Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 2007-08-27.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.