Arithmetic

Arithmetic or arithmetics (from the Greek word αριθμός, meaning "number") is the oldest and most elementary branch of mathematics, used by almost everyone, for tasks ranging from simple daily counting to advanced science and business calculations. In common usage, the word refers to a branch of (or the forerunner of) mathematics which records elementary properties of certain operations on numbers. Professional mathematicians sometimes use the term higher arithmetic[1] as a synonym for number theory, but this should not be confused with elementary arithmetic.

History

The prehistory of arithmetic is limited by a very small number of small artifacts indicating a clear conception of addition and subtraction, the best-known being the Ishango Bone from Africa, dating from 18,000 B.C.E.

It is clear that the Babylonians had solid knowledge of almost all aspects of elementary arithmetic circa 1850 B.C.E., historians can only infer the methods utilized to generate the arithmetical results (see Plimpton 322). Likewise, a definitive algorithm for multiplication and the use of unit fractions can be found in the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus dating from Ancient Egypt circa 1650 B.C.E.

In the Pythagorean school, in the second half of the 6th century B.C.E., arithmetic was considered one of the four quantitative or mathematical sciences (Mathemata). These were carried over in mediæval universities as the Quadrivium which, together with the Trivium of grammar, rhetoric and dialectic, constituted the septem liberales artes (seven liberal arts).

Modern algorithms for arithmetic (both for hand and electronic computation) were made possible by the introduction of Arabic numerals and decimal place notation for numbers. Although it is now considered elementary, its simplicity is the culmination of thousands of years of mathematical development. By contrast, the ancient mathematician Archimedes devoted an entire work, The Sand Reckoner, to devising a notation for a certain large integer. The flourishing of algebra in the medieval Islamic world and in Renaissance Europe was an outgrowth of the enormous simplification of computation through decimal notation.

Decimal arithmetic

Decimal notation constructs all real numbers from the basic digits, the first ten non-negative integers 0,1,2,...,9. A decimal numeral consists of a sequence of these basic digits, with the "denomination" of each digit depending on its position with respect to the decimal point: for example, 507.36 denotes 5 hundreds (102), plus 0 tens (101), plus 7 units (100), plus 3 tenths (10-1) plus 6 hundredths (10-2). An essential part of this notation (and a major stumbling block in achieving it) was conceiving of 0 as a number comparable to the other basic digits.

Algorism comprises all of the rules of performing arithmetic computations using a decimal system for representing numbers in which numbers written using ten symbols having the values 0 through 9 are combined using a place-value system (positional notation), where each symbol has ten times the weight of the one to its right. This notation allows the addition of arbitrary numbers by adding the digits in each place, which is accomplished with a 10 x 10 addition table. (A sum of digits which exceeds 9 must have its 10-digit carried to the next place leftward.) One can make a similar algorithm for multiplying arbitrary numbers because the set of denominations {...,102,10,1,10-1,...} is closed under multiplication. Subtraction and division are achieved by similar, though more complicated algorithms.

Arithmetic operations

The traditional arithmetic operations are addition, subtraction, multiplication and division, although more advanced operations (such as manipulations of percentages, square root, exponentiation, and logarithmic functions) are also sometimes included in this subject. Arithmetic is performed according to an order of operations. Any set of objects upon which all four operations of arithmetic can be performed (except division by zero), and wherein these four operations obey the usual laws, is called a field.

Addition (+)

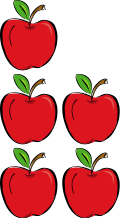

Addition is the basic operation of arithmetic. In its simplest form, addition combines two numbers, the addends or terms, into a single number, the sum.

Adding more than two numbers can be viewed as repeated addition; this procedure is known as summation and includes ways to add infinitely many numbers in an infinite series; repeated addition of the number one is the most basic form of counting.

Addition is commutative and associative so the order in which the terms are added does not matter. The identity element of addition (the additive identity) is 0, that is, adding zero to any number will yield that same number. Also, the inverse element of addition (the additive inverse) is the opposite of any number, that is, adding the opposite of any number to the number itself will yield the additive identity, 0. For example, the opposite of 7 is (-7), so 7 + (-7) = 0.

777777777

Addition is the mathematical operation of increasing one amount by another. The result of adding two quantities a and b is their sum, a + b; it is a more than b, and b more than a. For example, 3 + 2 = 5, since 5 is 2 more than 3. Addition also models many related processes, including joining two collections of objects, repeated incrementation, moving a point across the number line, and representing two successive translations as one.

Performing addition is one of the simplest numerical tasks, accessible to infants as young as five months and even some animals.

In formal mathematics, a binary operation called "addition" is defined on many sets of numbers. Essential contexts include the natural numbers, the integers, the rational numbers, and the real numbers. These addition operations extend to more complicated objects such as matrices and polynomials.

Adding more than two numbers can be viewed as repeated addition; this procedure is known as summation and includes ways to add infinitely many numbers in an infinite series. Repeated addition of the number one is the most basic form of counting.

Notation and terminology

Addition is written using the plus sign "+" between the terms; that is, in infix notation. The result is expressed with an equals sign. For example,

- 1 + 1 = 2

- 2 + 2 = 4

- 5 + 4 + 2 = 11 (see "associativity" below)

- 3 + 3 + 3 + 3 = 12 (see "multiplication" below)

There are also situations where addition is "understood" even though no symbol appears:

- A column of numbers, with the last number in the column underlined, usually indicates that the numbers in the column are to be added, with the sum written below the underlined number.

- A whole number followed immediately by a fraction indicates the sum of the two, called a mixed number.[3] For example,

31⁄2 = 3 + 1⁄2 = 3.5.

This notation can cause confusion, since in most other contexts, juxtaposition denotes multiplication instead.

The numbers or the objects to be added are generally called the "terms", the "addends", or the "summands"; this terminology carries over to the summation of multiple terms. This is to be distinguished from factors, which are multiplied. Some authors call the first addend the augend. In fact, during the Renaissance, many authors did not consider the first addend an "addend" at all. Today, due to the symmetry of addition, "augend" is rarely used, and both terms are generally called addends.[4]

Subtraction (−)

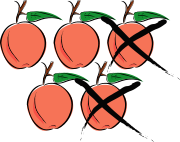

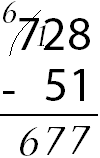

Subtraction is essentially the opposite of addition. Subtraction finds the difference between two numbers, the minuend minus the subtrahend. If the minuend is larger than the subtrahend, the difference will be positive; if the minuend is smaller than the subtrahend, the difference will be negative; and if they are equal, the difference will be zero.

Subtraction is neither commutative nor associative. For that reason, it is often helpful to look at subtraction as addition of the minuend and the opposite of the subtrahend, that is a − b = a + (−b). When written as a sum, all the properties of addition hold.

7777777777

Subtraction is one of the four basic arithmetic operations; it is essentially the opposite of addition. Subtraction is denoted by a minus sign in infix notation.

The traditional names for the parts of the formula

- c − b = a

are minuend (c) − subtrahend (b) = difference (a). The words "minuend" and "subtrahend" are virtually absent from modern usage; Linderholm charges "This terminology is of no use whatsoever."[5] However, "difference" is very common.

Subtraction is used to model several closely related processes:

- From a given collection, take away (subtract) a given number of objects.

- Combine a given measurement with an opposite measurement, such as a movement right followed by a movement left, or a deposit and a withdrawal.

- Compare two objects to find their difference. For example, the difference between $800 and $600 is $800 − $600 = $200.

In mathematics, it is often useful to view or even define subtraction as a kind of addition, the addition of the opposite. We can view 7 − 3 = 4 as the sum of two terms: seven and negative three. This perspective allows us to apply to subtraction all of the familiar rules and nomenclature of addition. Subtraction is not associative or commutative— in fact, it is anticommutative— but addition of signed numbers is both.

Basic subtraction: integers

Imagine a line segment of length b with the left end labeled a and the right end labeled c. Starting from a, it takes b steps to the right to reach c. This movement to the right is modeled mathematically by addition:

- a + b = c.

From c, it takes b steps to the left to get back to a. This movement to the left is modeled by subtraction:

- c − b = a.

Now, imagine a line segment labelled with the numbers 1, 2, and 3. From position 3, it takes no steps to the left to stay at 3, so 3 − 0 = 3. It takes 2 steps to the left to get to position 1, so 3 − 2 = 1. This picture is inadequate to describe what would happen after going 3 steps to the left of position 3. To represent such an operation, the line must be extended.

To subtract arbitrary natural numbers, one begins with a line containing every natural number (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, ...). From 3, it takes 3 steps to the left to get to 0, so 3 − 3 = 0. But 3 − 4 is still invalid since it again leaves the line. The natural numbers are not a useful context for subtraction.

The solution is to consider the integer number line (…, −3, −2, −1, 0, 1, 2, 3, …). From 3, it takes 4 steps to the left to get to −1, so

- 3 − 4 = −1.

Multiplication (× or ·)

Multiplication is in essence repeated addition, or the sum of a list of identical numbers. Multiplication finds the product of two numbers, the multiplier and the multiplicand, sometimes both just called factors.

Multiplication, as it is really repeated addition, is commutative and associative; further it is distributive over addition and subtraction. The multiplicative identity is 1, that is, multiplying any number by 1 will yield that same number. Also, the multiplicative inverse is the reciprocal of any number, that is, multiplying the reciprocal of any number by the number itself will yield the multiplicative identity, 1.

77777777777 In mathematics, multiplication is an elementary arithmetic operation. When one of the numbers is a whole number, multiplication is the repeated sum of the other number.

For example, 7 × 4 is the same as 7 + 7 + 7 + 7.

Fractions are multiplied by separately multiplying their denominators and numerators: a/b × c/d = (ac)/(bd). For example, 2/3 × 3/4 = (2×3)/(3×4) = 6/12 = 1/2.

Multiplication can be defined for real and complex numbers, polynomials, matrices and other mathematical quantities as well. The inverse of multiplication is division.

Computation

For several ways to compute products, including very large numbers, see multiplication algorithms.

The standard methods for multiplying numbers using pencil and paper require a multiplication table of memorized or consulted products of small numbers (typically any two numbers from 0 to 9), however one method, the peasant multiplication algorithm, does not.

Multiplying numbers to more than a couple of decimal places by hand is tedious and error prone. Common logarithms were invented to simplify such calculations. The slide rule allowed numbers to be quickly multiplied to about three places of accuracy. Beginning in the early twentieth century, mechanical calculators, such as the Marchant, automated multiplication of up to 10 digit numbers. Modern electronic computers and calculators have greatly reduced the need for multiplication by hand.

Terminology

The two numbers being multiplied are formally called the multiplicand and the multiplier, respectively. (Some write the multiplier first, and say that 7 × 4 stands for 4 + 4 + 4 + 4 + 4 + 4 + 4, but this usage is less common.) The difference was important in Roman numerals and similar systems where multiplication is transformation of symbols and their addition. For example, to multiply VII by XV one changes the VII to LXX (multiplying VII by X) plus XXV (V times V) plus X (II times V), but to multiply XV by VII one changes XV into LXXV (XV times V) plus XV plus XV (each XV times I).

Because of the commutative property of multiplication, there is generally no need to distinguish between the two numbers so they are more commonly referred to as the factors. The result of the multiplication is referred to as the product.

Notation

Multiplication can be denoted in several equivalent ways. All of the following mean, "5 multiplied by 2":

- 5×2

- 5·2

- (5)2, 5(2), (5)(2), 5[2], [5]2, [5][2]

- 5*2

- 5.2

The asterisk (*) is often used on computers because it is a symbol on every keyboard, but it is rarely used when writing math by hand. This usage originated in the FORTRAN programming language. Frequently, multiplication is implied by Juxtaposition rather than shown in a notation. This is standard in algebra, taking forms like

- 5x and xy

This notation is potentially confusing if variables are permitted to have names longer than one letter, as in computer programming languages. The notation is not used with numbers alone: 52 never means 5 × 2.

If the terms are not written out individually, then the product may be written with an ellipsis to mark out the missing terms, as with other series operations (like sums). Thus, the product of all the natural numbers from 1 to 100 can be written . This can also be written with the ellipsis vertically placed in the middle of the line, as .

Capital pi notation

Alternatively, a product can be written with the product symbol, which derives from the capital letter Π (Pi) in the Greek alphabet. Unicode position U+220F (∏) is defined a n-ary product for this purpose, distinct from U+03A0 (Π), the letter. This is defined as:

The subscript gives the symbol for a dummy variable ( in our case) and its lower value (); the superscript gives its upper value. So for example:

In case m = n, the value of the product is the same as that of the single factor xm. If m > n, the product is the empty product, with the value 1.

Infinite products

One may also consider products of infinitely many terms; these are called infinite products. Notationally, we would replace n above by the infinity symbol (∞). In the reals, the product of such a series is defined as the limit of the product of the first terms, as grows without bound. That is:

One can similarly replace with negative infinity, and

for some integer , provided both limits exist.

Interpretation

Cartesian product

The definition of multiplication as repeated addition provides a way to arrive at a set-theoretic interpretation of multiplication of cardinal numbers. In , if the n copies of a are to be combined in disjoint union then clearly they must be made disjoint; an obvious way to do this is to use either a or n as the indexing set for the other. Then, the members of are exactly those of the Cartesian product . The properties of the multiplicative operation as applying to natural numbers then follow trivially from the corresponding properties of the Cartesian product.

Properties

For integers, fractions, real and complex numbers, multiplication has certain properties:

- the order in which two numbers are multiplied does not matter. This is called the commutative property,

- x · y = y · x.

- The associative property means that for any three numbers x, y, and z,

- (x · y)z = x(y · z).

- Note from algebra: the parentheses mean that the operations inside the parentheses must be done before anything outside the parentheses is done.

- Multiplication also has what is called a distributive property with respect to the addition,

- x(y + z) = xy + xz.

- Also of interest is that any number times 1 is equal to itself, thus,

- 1 · x = x.

- and this is called the identity property. In this regard the number 1 is known as the multiplicative identity.

- The sum of zero numbers is zero.

- This fact is directly received by means of the distributive property:

- m · 0 = (m · 0) + m − m = (m · 0) + (m · 1) − m = m · (0 + 1) − m = (m · 1) − m = m − m = 0.

- So,

- m · 0 = 0

- no matter what m is (as long as it is finite).

- Multiplication with negative numbers also requires a little thought. First consider negative one (-1). For any positive integer m:

- (−1)m = (−1) + (−1) +...+ (−1) = −m

- This is an interesting fact that shows that any negative number is just negative one multiplied by a positive number. So multiplication with any integers can be represented by multiplication of whole numbers and (−1)'s.

- All that remains is to explicitly define (−1)(−1):

- (−1)(−1) = −(−1) = 1

- However, from a formal viewpoint, multiplication between two negative numbers is (again) directly received by means of the distributive property, e.g:

| (−1) × (−1) | |

| = (−1) × (−1) + (−2) + 2 | |

| = (−1) × (−1) + (−1) × 2 + 2 | |

| = (−1) × (−1 + 2) + 2 | |

| = (−1) × 1 + 2 | |

| = (−1) + 2 | |

| = 1 |

- Every number x, except zero, has a multiplicative inverse, 1/x, such that x × 1/x = 1.

- Multiplication by a positive number preserves order: if a > 0, then if b > c then ab > ac. Multiplication by a negative number reverses order: if a < 0, then if b > c then ab < ac.

Other mathematical systems that include a multiplication operation may not have all these properties. For example, multiplication is not, in general, commutative for matrices and quaternions.

Division (÷ or /)

Division is essentially the opposite of multiplication. Division finds the quotient of two numbers, the dividend divided by the divisor. Any dividend divided by zero is undefined. For positive numbers, if the dividend is larger than the divisor, the quotient will be greater than one, otherwise it will be less than one (a similar rule applies for negative numbers and negative one). The quotient multiplied by the divisor always yields the dividend.

Division is neither commutative nor associative. As it is helpful to look at subtraction as addition, it is helpful to look at division as multiplication of the dividend times the reciprocal of the divisor, that is a ÷ b = a × 1⁄b. When written as a product, it will obey all the properties of multiplication.

7777777777 In mathematics, especially in elementary arithmetic, division is an arithmetic operation which is the inverse of multiplication.

Specifically, if c times b equals a, written:

where b is not zero, then a divided by b equals c, written:

For instance,

since

- .

In the above expression, a is called the dividend, b the divisor and c the quotient.

Division by zero (i.e. where the divisor is zero) is usually not defined.

Notation

Division is most often shown by placing the dividend over the divisor with a horizontal line, also called a vinculum, between them. For example, a divided by b is written

This can be read out loud as "a divided by b" or "a over b". A way to express division all on one line is to write the dividend, then a slash, then the divisor, like this:

This is the usual way to specify division in most computer programming languages since it can easily be typed as a simple sequence of characters.

A typographical variation which is halfway between these two forms uses a slash but elevates the dividend, and lowers the divisor:

- a⁄b .

Any of these forms can be used to display a fraction. A fraction is a division expression where both dividend and divisor are integers (although typically called the numerator and denominator), and there is no implication that the division needs to be evaluated further.

A less common way to show division is to use the obelus (or division sign) in this manner:

This form is infrequent except in elementary arithmetic. The obelus is also used alone to represent the division operation itself, as for instance as a label on a key of a calculator.

In some non-English-speaking cultures, "a divided by b" is written a : b. However, in English usage the colon is restricted to expressing the related concept of ratios (then "a is to b").

Examples

Addition table

|

Multiplication table

|

Number theory

The term arithmetic is also used to refer to number theory. This includes the properties of integers related to primality, divisibility, and the solution of equations by integers, as well as modern research which is an outgrowth of this study. It is in this context that one runs across the fundamental theorem of arithmetic and arithmetic functions. A Course in Arithmetic by Serre reflects this usage, as do such phrases as first order arithmetic or arithmetical algebraic geometry. Number theory is also referred to as 'the higher arithmetic', as in the title of H. Davenport's book on the subject.

Arithmetic in education

Primary education in mathematics often places a strong focus on algorithms for the arithmetic of natural numbers, integers, rational numbers (vulgar fractions), and real numbers (using the decimal place-value system). This study is sometimes known as algorism.

The difficulty and unmotivated appearance of these algorithms has long led educators to question this curriculum, advocating the early teaching of more central and intuitive mathematical ideas. One notable movement in this direction was the New Math of the 1960s and '70s, which attempted to teach arithmetic in the spirit of axiomatic development from set theory, an echo of the prevailing trend in higher mathematics [6].

Since the introduction of the electronic calculator, which can perform the algorithms far more efficiently than humans, an influential school of educators has argued that mechanical mastery of the standard arithmetic algorithms is no longer necessary. In their view, the first years of school mathematics could be more profitably spent on understanding higher-level ideas about what numbers are used for and relationships among number, quantity, measurement, and so on. However, most research mathematicians still consider mastery of the manual algorithms to be a necessary foundation for the study of algebra and computer science. This controversy was central to the "Math Wars" over California's primary school curriculum in the 1990s, and continues today [7].

See also

- Addition of natural numbers

- Additive inverse

- Associativity

- Commutativity

- Distributivity

- Elementary arithmetic

- Finite field arithmetic

- Number line

- Important publications in arithmetic

- Arithmetic coding

- Arithmetic mean

- Arithmetic progression

Footnotes

- ↑ Davenport, Harold (1999). The Higher Arithmetic: An Introduction to the Theory of Numbers (7th ed.). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-63446-6.

- ↑ From Enderton (p.138): "...select two sets K and L with card K = 2 and card L = 3. Sets of fingers are handy; sets of apples are preferred by textbooks."

- ↑ Devine et al p.263

- ↑ Schwartzman p.19

- ↑ Linderholm p.42

- ↑ http://www.mathematicallycorrect.com/glossary.htm

- ↑ http://www.education-world.com/a_curr/curr071.shtml

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Cunnington, Susan. The story of arithmetic, a short history of its origin and development. Swan Sonnenschein, London, 1904.

- Dickson, Leonard Eugene. History of the theory of numbers. Three volumes. Reprints: Carnegie Institute of Washington, Washington, 1932. Chelsea, New York, 1952, 1966.

- Fine, Henry Burchard (1858-1928). The number system of algebra treated theoretically and historically. Leach, Shewell & Sanborn, Boston, 1891.

- Karpinski, Louis Charles (1878-1956). The history of arithmetic. Rand McNally, Chicago, 1925. Reprint: Russell & Russell, New York, 1965.

- Ore, Øystein. Number theory and its history. McGraw-Hill, New York, 1948.

- Weil, Andre. Number theory: an approach through history. Birkhauser, Boston, 1984. Reviewed: Math. Rev. 85c:01004.

External links

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Arithmetic history

- Addition history

- Subtraction history

- Multiplication history

- Division_(mathematics) history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.