Difference between revisions of "Cell membrane" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

Transport across the cell membrane underlies a variety of physiological processes, from the beating of an animal’s heart to the opening of tiny pores in leaves that enables gas exchange with the environment. A major cellular manifestation of [[motor neuron disease]] is the lack of ability of nerve cells to stimulate the opening of channels through muscle cell membranes that would result in normal muscle function. | Transport across the cell membrane underlies a variety of physiological processes, from the beating of an animal’s heart to the opening of tiny pores in leaves that enables gas exchange with the environment. A major cellular manifestation of [[motor neuron disease]] is the lack of ability of nerve cells to stimulate the opening of channels through muscle cell membranes that would result in normal muscle function. | ||

| − | Although the regulation of transport is a crucial role, it is not the only function of the cell membrane. Cell membranes are also involved in biological communication. The binding of a specific substance to the exterior of the membrane can initiate, modify, or turn off a cell function. In nerve cells, the cell membrane is the conductor of the nerve impulse from one end of the cell to the other. Cell membranes also help in the organization of individual cells to form [[tissue]]s | + | Although the regulation of transport is a crucial role, it is not the only function of the cell membrane. Cell membranes are also involved in biological communication. The binding of a specific substance to the exterior of the membrane can initiate, modify, or turn off a cell function. In nerve cells, the cell membrane is the conductor of the nerve impulse from one end of the cell to the other. Cell membranes also help in the organization of individual cells to form [[tissue]]s through processes of [[cellular recognition]] and [[cellular adhesion]]. |

| − | + | ||

In [[animal]] cells, the cell membrane establishes this separation alone, whereas in yeast, bacteria and plants an additional [[cell wall]] forms the outermost boundary, providing primarily mechanical support. | In [[animal]] cells, the cell membrane establishes this separation alone, whereas in yeast, bacteria and plants an additional [[cell wall]] forms the outermost boundary, providing primarily mechanical support. | ||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

====Lipids==== | ====Lipids==== | ||

[[Image:Basic_lipid_structure.png|frame|150px|The phospholipid shown has a polar head group (<font color="#AA0000">P</font>) and a nonpolar tail (<font color="#0000AA">U</font> for unpolar). This amphipathic quality enables the phospholipid components of the cell membrane to self-organize into a lipid bilayer.]] | [[Image:Basic_lipid_structure.png|frame|150px|The phospholipid shown has a polar head group (<font color="#AA0000">P</font>) and a nonpolar tail (<font color="#0000AA">U</font> for unpolar). This amphipathic quality enables the phospholipid components of the cell membrane to self-organize into a lipid bilayer.]] | ||

| − | The three major types of lipid found in the cell membrane are [[phospholipid]]s, [[ | + | The three major types of lipid found in the cell membrane are [[phospholipid]]s, [[glycolipid]]s, and [[cholesterol]] molecules. A phospholipid is composed of a polar head (a negatively charged phosphate group) and two non-polar tails (the two [[fatty acid]] chains). Phospholipids are said to be '''amphipathic''' molecules because they contain both a [[hydrophilic]] (water-loving) head and [[hydrophobic]] (water-fearing) tails. This amphipathic property causes phospholipids to organize into a spherical, three-dimensional lipid bilayer around the cell. Within the aqueous environment of the body, the polar heads of lipids tend to orient outward to interact with water molecules, while the hydrophobic tails tend to minimize their contact with water by clustering together internally. |

The length and properties of the fatty-acid components of phospholipids determine the fluidity of the cell membrane. At reduced temperatures, some organisms may vary the type and relative amounts of constituent lipids to maintain the fluidity of their membranes—these changes contribute to the survival of plants, bacteria, and hibernating animals during winter. | The length and properties of the fatty-acid components of phospholipids determine the fluidity of the cell membrane. At reduced temperatures, some organisms may vary the type and relative amounts of constituent lipids to maintain the fluidity of their membranes—these changes contribute to the survival of plants, bacteria, and hibernating animals during winter. | ||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

The regulation of membrane fluidity is assisted by another lipid, [[cholesterol]], which is primarily found in [[eukaryote]]s. | The regulation of membrane fluidity is assisted by another lipid, [[cholesterol]], which is primarily found in [[eukaryote]]s. | ||

| − | Carbohydrate components are linked to lipids (to form ' | + | Carbohydrate components are linked to lipids (to form ''glycolipids'') or to proteins (''glycoproteins'') on the outside of the cell membrane. They are crucial in recognizing specific molecules or other cells. For example, the carbohydrate unit of some glycolipids changes when a cell becomes cancerous, which may allow white blood cells to target cancer cells for destruction. |

====Proteins==== | ====Proteins==== | ||

Cell membranes contain two types of proteins: | Cell membranes contain two types of proteins: | ||

| − | *''Extrinsic'' or ''Peripheral'' proteins | + | *''Extrinsic'' or ''Peripheral'' proteins simply adhere to the membrane and are bound by polar interactions. |

| − | *' | + | *''Intrinsic proteins'' or [[integral membrane proteins]] may be said to reside within it or to span the membrane. They interact extensively with the hydrocarbon chains of membrane lipids and can be released only by agents that compete for these nonpolar interactions. |

(proteins do x,y,z) | (proteins do x,y,z) | ||

| Line 55: | Line 55: | ||

==Other functions of cell membranes== | ==Other functions of cell membranes== | ||

| − | + | #''Structure''. It? attaches parts of the [[cytoskeleton]] to the cell membrane in order to provide shape. | |

| − | #Structure. It? attaches parts of the [[cytoskeleton]] to the cell membrane in order to provide shape. | + | #''Organization''. It? attaches cells to an extra-cellular matrix in grouping cells together to form tissues (adhesion). |

| − | #Organization. It? attaches cells to an extra-cellular matrix in grouping cells together to form tissues (adhesion). | + | #''Information processing''. It acts as receptor for the various chemical messages which pass between cells. The movement of bacteria toward food and the response of target cells to hormones such as insulin are two examples of processes that hinge on the detection of a signal by a specific receptor in a cell membrane. |

| − | #Information processing. It acts as receptor for the various chemical messages which pass between cells. The movement of bacteria toward food and the response of target cells to hormones such as insulin are two examples of processes that hinge on the detection of a signal by a specific receptor in a cell membrane. | + | #''Enzyme assembly''. Cell membranes can serve as an assembly that organizes enzymes bound to the membrane in sequential order, to enable an efficient occurrence of a series of chemical reactions (metabolism). |

| − | #Enzyme assembly. Cell membranes can serve as an assembly that organizes enzymes bound to the membrane in sequential order, to enable an efficient occurrence of a series of chemical reactions (metabolism). | + | #''Maintaining cell potential''. Cell membranes of nerve cells, muscle cells, and some eggs are excitable electrically. In nerve cells, for example, the plasma membrane conducts the nerve impulse from one end of the cell to the other. |

| − | #Maintaining cell potential. Cell membranes of nerve cells, muscle cells, and some eggs are excitable electrically. In nerve cells, for example, the plasma membrane conducts the nerve impulse from one end of the cell to the other. | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

Revision as of 17:16, 8 December 2006

The cell membrane (or plasma membrane) is the thin outer layer of the cell that differentiates the cell from its environment. As a semi-permeable barrier, it keeps out toxic or unwanted substances, while enabling the selective, controlled flow of nutrients into the cell: a balance essential for life.

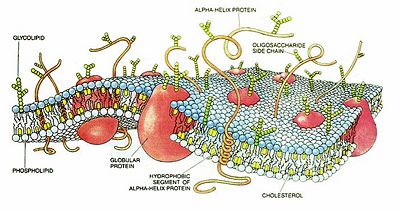

The cell membrane is composed mainly of lipid and protein molecules arranged in organized but flexible sheets. The lipid components form a bilayer that contributes structural stability and creates a semi-permeable environment. The proteins are responsible for most of the dynamic processes carried out by cell membranes, such as the transport of molecules into and out of the cell.

Transport across the cell membrane underlies a variety of physiological processes, from the beating of an animal’s heart to the opening of tiny pores in leaves that enables gas exchange with the environment. A major cellular manifestation of motor neuron disease is the lack of ability of nerve cells to stimulate the opening of channels through muscle cell membranes that would result in normal muscle function.

Although the regulation of transport is a crucial role, it is not the only function of the cell membrane. Cell membranes are also involved in biological communication. The binding of a specific substance to the exterior of the membrane can initiate, modify, or turn off a cell function. In nerve cells, the cell membrane is the conductor of the nerve impulse from one end of the cell to the other. Cell membranes also help in the organization of individual cells to form tissues through processes of cellular recognition and cellular adhesion.

In animal cells, the cell membrane establishes this separation alone, whereas in yeast, bacteria and plants an additional cell wall forms the outermost boundary, providing primarily mechanical support.

The structure of cell membranes

Components

Lipids

The three major types of lipid found in the cell membrane are phospholipids, glycolipids, and cholesterol molecules. A phospholipid is composed of a polar head (a negatively charged phosphate group) and two non-polar tails (the two fatty acid chains). Phospholipids are said to be amphipathic molecules because they contain both a hydrophilic (water-loving) head and hydrophobic (water-fearing) tails. This amphipathic property causes phospholipids to organize into a spherical, three-dimensional lipid bilayer around the cell. Within the aqueous environment of the body, the polar heads of lipids tend to orient outward to interact with water molecules, while the hydrophobic tails tend to minimize their contact with water by clustering together internally.

The length and properties of the fatty-acid components of phospholipids determine the fluidity of the cell membrane. At reduced temperatures, some organisms may vary the type and relative amounts of constituent lipids to maintain the fluidity of their membranes—these changes contribute to the survival of plants, bacteria, and hibernating animals during winter.

The regulation of membrane fluidity is assisted by another lipid, cholesterol, which is primarily found in eukaryotes.

Carbohydrate components are linked to lipids (to form glycolipids) or to proteins (glycoproteins) on the outside of the cell membrane. They are crucial in recognizing specific molecules or other cells. For example, the carbohydrate unit of some glycolipids changes when a cell becomes cancerous, which may allow white blood cells to target cancer cells for destruction.

Proteins

Cell membranes contain two types of proteins:

- Extrinsic or Peripheral proteins simply adhere to the membrane and are bound by polar interactions.

- Intrinsic proteins or integral membrane proteins may be said to reside within it or to span the membrane. They interact extensively with the hydrocarbon chains of membrane lipids and can be released only by agents that compete for these nonpolar interactions.

(proteins do x,y,z)

The relative number of proteins and lipids depends on the specialized function of the cell. For example, myelin, a membrane that encloses some nerve cells, uses properties of lipids to act as an insulator, and so contains only one protein per 70 lipids. In general, however, most cell membranes are about 50 percent protein by weight.

The fluid-mosaic model

The cell membrane is often described as a fluid mosaic – a two-dimensional fluid of freely diffusing lipids, dotted or embedded with proteins, which may function as channels or transporters across the membrane, or as receptors. The model was first proposed by S. Jonathan Singer (1971) as a lipid protein model and extended to include the fluid character in a publication with Garth L. Nicolson in ‘’Science’’ (1972). Proteins are free to diffuse laterally in the lipid matrix unless restricted by specific interactions, but not to rotate from one side of the membrane to another.

Transport across the cell membrane

As the cell membrane is semi-permeable, only some molecules can pass unhindered into or out of the cell. These molecules are either small or lipophilic. The cell membrane has a low permeability to ions and most polar molecules, with water being a notable exception.

There are two major mechanisms for moving chemical substances across membranes: passive transport (which does not require the input of outside energy) and active transport (which is driven by the direct or indirect input of chemical energy ATP).

Passive transport

Passive transport processes rely on a concentration gradient (a difference in concentration on the two sides of the membrane). This spontaneous process decreases free energy and increases entropy in a system. There are two types of passive transport:

- Simple diffusion of hydrophobic (non-polar) and small polar molecules through the phospholipids bilayer, and

- Facilitated diffusion of polar and ionic molecules, which relies on a transport protein to provide a channel or bind to specific molecules. Channels form continuous polar pathways across membranes that allow ions to flow rapidly down their electrochemical gradients (i.e., in a thermodynamically favorable direction).

Active transport

Charged or polar molecules (such as amino acids, sugars, and ions) do not pass readily through the lipid bilayer. Protein pumps use a source of free energy like ATP or light to drive the uphill transport. That is, active transport typically moves molecules against their electrochemical gradient, the process that would be entropically unfavorable were it not coupled with the hydrolysis of ATP. This coupling can be either primary or secondary:

- Primary active transport involves the direct participation of ATP.

- In secondary active transport, transporters use energy derived from transport of another molecule in the direction of their gradient to move other molecules in the direction against their gradient.

In general, active transport is much slower than transport through channels.

The processes of endocytosis, which bring macromolecules, large particles, and even small cells into a eukaryotic cell, can be thought of as examples of active transport. In endocytosis, the plasma membrane folds inward around materials from the environment, forming a small pocket. The pocket deepens, forming a vesicle that separates from the membrane and migrates into the cell interior. In exocytosis, materials packaged in vesicles are exported from a cell when the vesicle membrane fuses with the cell membrane.

Other functions of cell membranes

- Structure. It? attaches parts of the cytoskeleton to the cell membrane in order to provide shape.

- Organization. It? attaches cells to an extra-cellular matrix in grouping cells together to form tissues (adhesion).

- Information processing. It acts as receptor for the various chemical messages which pass between cells. The movement of bacteria toward food and the response of target cells to hormones such as insulin are two examples of processes that hinge on the detection of a signal by a specific receptor in a cell membrane.

- Enzyme assembly. Cell membranes can serve as an assembly that organizes enzymes bound to the membrane in sequential order, to enable an efficient occurrence of a series of chemical reactions (metabolism).

- Maintaining cell potential. Cell membranes of nerve cells, muscle cells, and some eggs are excitable electrically. In nerve cells, for example, the plasma membrane conducts the nerve impulse from one end of the cell to the other.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Purves, William, David Sadava, Gordon Orians, & H. Craig Heller. 2004. “Life: The Science of Biology,” 7th edition. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer.

- Stryer, Lubert. 1995. Biochemistry, 4th edition. New York, NY: W.H. Freeman.

External links

- Lipids, Membranes and Vesicle Trafficking - The Virtual Library of Biochemistry and Cell Biology

- Cell membrane protein extraction protocol

- Membrane homeostasis, tension regulation, mechanosensitive membrane exchange and membrane traffic

| Organelles of the cell |

|---|

| Acrosome | Chloroplast | Cilium/Flagellum | Centriole | Endoplasmic reticulum | Golgi apparatus | Lysosome | Melanosome | Mitochondrion | Myofibril | Nucleus | Parenthesome | Peroxisome | Plastid | Ribosome | Vacuole | Vesicle |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.