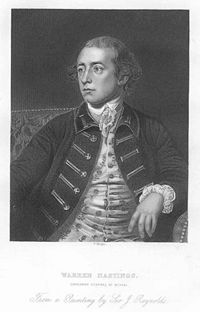

Warren Hastings

Warren Hastings (December 6, 1732 - August 22, 1818) was the first and most well-known governor-general of British India, from 1773 to 1785. He was famously impeached in 1787 for corruption, and acquitted in 1795. He was made a Privy Councilor in 1814. His contributions to establishing the British empire in India are noteworthy, especially in reference to his administrative feats. During his time as governor-general, Hastings was instrumental in implementing innovative reforms. He also was involved in two wars in the region. Hastings endured his impeachment trial with dignity, nearly bankrupting himself during the proceedings. Those who implicated him in any wrongdoing actually had little knowledge of the extent of work he had accomplished in British India.[1]

Hastings, unlike many of his successors, respected and admired Indian culture. On the one hand, he was more interested in India's past than he was in contemporary expressions of Indian culture. On the other hand, he did not share the disdain that many later British officials had for all things Indian, infamously expressed by Thomas Babbington Macauley. At this period in the history of the British Raj, some thought more in terms of a British-Indian partnership than of a guardian-ward, subject-object relationship of superior to inferior. His reputation among Indian nationalists though, is no better than that of other imperialists who robbed Indians of their freedom. Yet had those who followed him in authority viewed Indians with greater respect, they might have handled their aspirations for participation in governance differently, since what became the struggle for independence began as a call for participation and partnership and political empowerment, not separation.

Life

Hastings was born at Churchill, Oxfordshire.[2] He attended Westminster School[3] before joining the British East India Company in 1750 as a clerk. In 1757 he was made the British Resident (administrative in charge) of Murshidabad. He was appointed to the Calcutta council in 1761, but was back in England in 1764. He returned to India in 1769 as a member of the Madras council[4] and was made governor of Bengal in 1772.[5] In 1773, he was appointed the first Governor-General of India.[5]

After an eventful ten year tenure in which he greatly extended and regularized the nascent Raj created by Clive of India, Hastings resigned in 1784.[6] On his return to England he was charged with high crimes and misdemeanors by Edmund Burke, encouraged by Sir Philip Francis whom he had wounded in a duel in India. He was impeached in 1787 but the trial, which began in 1788, ended with his acquittal in 1795.[7] Hastings spent most of his fortune on his defense, although towards the end of the trial the East India Company did provide financial support.

He retained his supporters, however, and on August 22, 1806, the Edinburgh East India Club and a number of gentlemen from India gave what was described as "an elegant entertainment" to "Warren Hastings, Esq., late Governor-General of India," who was then on a visit to Edinburgh. One of the 'sentiments' drunk on the occasion was "Prosperity to our settlements in India, and may the virtue and talents which preserved them be ever remembered with gratitude."[8]

Impact on Indian history

In many respects Warren Hastings epitomizes the strengths and shortcomings of the British conquest and dominion over India. Warren Hastings went about consolidating British power in a highly systematic manner. They realized very early into their rule after they gained control over the vast lands of the Gangetic plain with a handful of British officers, that they would have to rely on the Indic to administer these vast areas. In so doing, he made a virtue out of necessity by realizing the importance of various forms of knowledge to the Colonial power, and in 1784 towards the end of his tenure as Governor general, he made the following remarks about the importance of various forms of knowledge, including linguistic, legal and scientific, for a colonial power and the case that such knowledge could be put to use for the benefit of his country Britain:

"Every application of knowledge and especially such as is obtained in social communication with people, over whom we exercise dominion, founded on the right of conquest, is useful to the state… It attracts and conciliates distant affections, it lessens the weight of the chain by which the natives are held in subjection and it imprints on the hearts of our countrymen the sense of obligation and benevolence… Every instance which brings their real character will impress us with more generous sense of feeling for their natural rights, and teach us to estimate them by the measure of our own… But such instances can only be gained in their writings; and these will survive when British domination in India shall have long ceased to exist, and when the sources which once yielded of wealth and power are lost to remembrance."[9]

During Hastings' time in this post, a great deal of precedent was established pertaining to the methods which the British Empire would use in its administration of India. Hastings had a great respect for the ancient scripture of Hinduism and fatefully set the British position on governance as one of looking back to the earliest precedents possible. This allowed Brahmin advisors to mold the law, as no Englishman understood Sanskrit until Sir William Jones; it also accentuated the caste system and other religious frameworks which had, at least in recent centuries, been somewhat incompletely applied. Thus, British influence on the ever-changing social structure of India can in large part be characterized as, for better or for worse, a solidification of the privileges of the caste system through the influence of the exclusively high-caste scholars by whom the British were advised in the formation of their laws. These laws also accepted the binary division of the people of Bengal and, by extension, India in general as either Muslim or Hindu (to be governed by their own laws). The British might therefore be said to be responsible to some extent for causing division, as they were both cause and effect of the forces which would eventually polarize Hindu and Muslim nationalists into the partition of India and the creation of Pakistan.

In 1781 Hastings founded Madrasa 'Aliya, meaning the higher madrasa, in Calcutta, showing his relations with the Muslim population.[10] In addition, in 1784 Hastings supported the foundation of the Bengal Asiatik Society (now Asiatic Society of Bengal) by the Orientalist Scholar William Jones, which became a storehouse for information and data pertaining to India.[11]

As Hastings had few Englishmen to carry out administrative work, and still fewer with the ability to converse in local tongues, he was forced to farm out revenue collection to locals with no ideological friendship for Company rule. Moreover, he was ideologically committed at the beginning of his rule to the administration being carried out by 'natives.' He believed that Europeans revenue collectors would "open the door to every kind of rapine and extortion" as there was "a fierceness in the European manners, especially among the lower sort, which is incompatible with the gentle temper of the Bengalee."[12]

British desire to assert themselves as the sole sovereign led to conflicts within this 'dual government' of Britons and Indians. The very high levels of revenue extraction and exportation of Bengali silver back to Britain had probably contributed to the famine of 1769-70, in which it has been estimated that a third of the population died; this led to the British characterizing the collectors as tyrants and blaming them for the ruin of the province.

Some Englishmen continued to be seduced by the opportunities to acquire massive wealth in India and as a result became involved in corruption and bribery, and Hastings could do little or nothing to stop it. Indeed it was argued (unsuccessfully) at his impeachment trial that he participated in the exploitation of these newly conquered lands.

Legacy

In 1818, in his old age, Hastings died after suffering through a prolonged illness for over a month.[13] He is buried at Daylesford Church, Oxfordshire close to Churchill.

In his Essay on Warren Hastings, Lord Macaulay, while impressed by the scale of Hastings' achievement in India, found that “His principles were somewhat lax. His heart was somewhat hard.”[14]

The nationalists in the subcontinent consider Hastings as another English bandit, along with Clive, who started the colonial rule in the subcontinent through treachery and cunning. However, it should be pointed out that other bandits, English or otherwise, did not found colleges and madrasas, nor helped to collect and translate Sanskrit works into English. In fact, later it became policy not to fund any Indian educations institutes but only Western style-learning.

In all, Hastings helped to accomplish a great deal in British India. When he first entered the region as governor-general he emerged onto a scene of disarray, rampant with corruption and treachery. Through his administrative innovations, Hastings was able to instate a degree of order in the region. His efforts effectively made it possible for Britain to more efficiently control its foreign empire. Hastings introduced several reforms to India and helped to quell social upheavals while serving there. When he was indicted on charges on misconduct upon returning to England, he was able to keep his composure and work out the situation over the lengthy seven year course of the trial, albeit at a costly financial expense to himself. Though India was still far from free of corruption after Hastings' tenure there had ended, the changes wrought by Hastings helped to ensure that its condition would improve a great deal as time progressed. The matters that Hastings brought to the attention of the British government proved to be vital to the mother country's later ability to effectively govern its foreign Indian holdings. After his acquittal, Hastings lived out the remainder of his life in Britain, where his good name and historical feats would be preserved until and after his death in 1818.[1]

Eponyms

The city of Hastings, New Zealand and the Melbourne outer suburb of Hastings, Victoria, Australia were both named after Warren Hastings.

Hastings is a Senior Wing House at St Paul's School, Darjeeling, India, where all the senior wing houses are named after colonial-age military figures.

| Government offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| New Title | Governor-General of India 1773–1785 |

Succeeded by: Sir John Macpherson, acting |

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Warren Hastings: 1732-1818 Heritage History. Retrieved May 20, 2008.

- ↑ Alfred Lyall, Warren Hastings (London, UK: Macmillan, 1915).

- ↑ Lyall, 1915, pg 2.

- ↑ Lyall, 1915, pgs 26-27.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Lyall, 1915, pg 29.

- ↑ Lyall, 1915, pg 164.

- ↑ Lyall, 1915, pg 224.

- ↑ William Matthews Gilbert (ed.), Edinburgh in the Nineteenth Century (Edinburgh, UK: J. & R. Allan, Ltd., 1901), 44.

- ↑ Bernard S. Cohn, Colonialism and its forms of knowledge: The British in India (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1996, ISBN 0691032939).

- ↑ Fazlur Rahman, Islam & Modernity (Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 1982, ISBN 0226702839), 73-74.

- ↑ John Keay, India: A History (New York, NY: Grove Press Books, 2000, ISBN 087113800X), 426.

- ↑ Mary Evelyn Monckton-Jones, Warren Hastings in Bengal (Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press, 1918), 156.

- ↑ Lyall, 1915, pg 232.

- ↑ Thomas Babington Macaulay, Macaulay's Essay on Warren Hasting (New York, NY: Macmillan, 1907), 129.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Cohn, Bernard S. 1997. Colonialism and its forms of knowledge: The British in India. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0691000433

- Forrest, George William (ed.). 1910. Selections from The State Papers of the Governors-General of India - Warren Hastings. 2 vols. Oxford, UK: Blackwell's.

- Gilbert, William Matthews (ed.). 1901. Edinburgh in the Nineteenth Century. Edinburgh, UK: J. & R. Allan, Ltd.

- Feiling, Keith Grahame. 1954. Warren Hastings. New York, NY: St. Martin's Press.

- Warren Hastings: 1732-1818 Heritage History. Retrieved May 20, 2008.

- Keay, John. 2000. India: A History. New York, NY: Grove Press Books, 2000. ISBN 0802137970

- Lyall, Alfred. 1915. Warren Hastings. London, UK: Macmillan.

- Marshall, Peter James. 1965. The Impeachment of Warren Hastings. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Macaulay, Thomas Babington. 1907. Macaulay's Essay on Warren Hasting. New York, NY: Macmillan.

- Macaulay, Thomas Babington. 1903. "Warren Hastings" pgs 63-174. In Montague, F. C. 1903. Critical and Historical Essays, vol. 3. London, UK: Methuen & Co. Retrieved May 20, 2008.

- Monckton-Jones, Mary Evelyn. 1918. Warren Hastings in Bengal. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press.

- Rahman, Fazlur. 1982. Islam & Modernity. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226702847

External links

All links retrieved May 3, 2023.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.