Glossolalia (from Greek glossa γλÏÏÏα "tongue, language" and lalĂŽ Î»Î±Î»Ï "speak, speaking") refers to ecstatic utterances, often as part of religious practices, commonly referred to as "speaking in tongues."

The origin of the modern Christian concept of speaking in tongues is the miracle of Pentecost, recounted in the New Testament book of Acts, in which Jesus' apostles were said to be filled with the Holy Spirit and spoke in languages foreign to themselves, but which could be understood by members of the linguistically diverse audience.

After the Protestant Reformation, speaking in tongues was sometimes witnessed in the revivals of the Great Awakening and meetings of the early Quakers. It was not until the twentieth century, however, that tongues became a widespread phenomenon, beginning with the Azusa Street Revival, which sparked the movement of contemporary Pentecostalism.

The word glossolalia was first used by the English theological writer, Frederic William Farrar, in 1879 (Oxford English Dictionary. The term xenoglossy, meaning "uttering intelligible words of a language unknown to the speaker," is sometimes used interchangeably with glossolalia, while at other times it is used to differentiate whether or not the utterances are intelligible as a natural language.

While occurrences of glossolalia are widespread and well documented, there is considerable debate within religious communities (principally Christian) as to both its repute and its source.

Christian practice

Glossolalia is practiced by a number of contemporary Christians within select Christian denominations. These groups see it as a revival of a practice from the early church in addition to a fulfillment of Old Testament prophecy (Isaiah 28:11-12, Joel 2:28).

New Testament

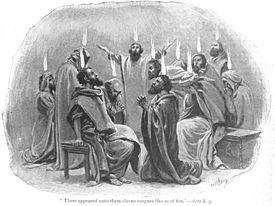

In the New Testament, the Acts 2:1-5 recounts how "tongues of fire" descended upon the heads of the Apostles, accompanied by the miraculous occurrence of speaking in languages unknown to them, but recognizable to others present as their own native language.

Are not all these men who are speaking Galileans? Then how is it that each of us hears them in his own native language? Parthians, Medes and Elamites; residents of Mesopotamia, Judea and Cappadocia, Pontus and Asia, Phrygia and Pamphylia, Egypt and the parts of Libya near Cyrene; visitors from Rome, both Jews and converts to JudaismâCretans and Arabsâwe hear them declaring the wonders of God in our own tongues! (Acts 2:7-11)

Orthodox hymns sung at the Feast of Pentecost, which commemorates this event in Acts, describe it as a reversal of the Tower of Babel events as described in Genesis 11. There, the languages of humanity were differentiated, leading to confusion, but at Pentecost all understood the language spoke by the Apostles, resulting in the immediate proclamation of the Gospel to Jewish pilgrims who were gathered in Jerusalem from many different countries.

Biblical descriptions of persons actually speaking in tongues occur three times in the book of Acts, the first two coupled with the phenomenon of the Baptism with the Holy Spirit, and the third with the laying on of hands by Paul the Apostle (at which time converts "received the Holy Spirit"), which imbued them with the power of the Holy Spirit (Acts 2:4, 10:46, 19:6). Speaking in tongues was also practiced in church services in first century Corinth.

Critics of contemporary glossolalia often point to Paul's first letter to the Corinthian church, in which he attempts to correct its particular tradition regarding speaking in tongues. Paul affirmed that speaking in tongues is only one of the gifts of the Spirit and is not given to all (1 Cor 12:12-31). Paul also cautioned the church on the disorderly manner in which they approached this practice. However, he never disqualified the practice, writing: "Do not forbid speaking in tongues" (1 Cor 14:39). Paul gave credence to it by admitting he wished that "all spoke with tongues" (1 Cor 14:5) and that he himself engaged in the practice (1 Cor 14:18).

Nevertheless, Paul was concerned that unbelievers who walked into the assembly would think the brethren "mad" (1 Cor 14:23, 27) because of their liberal use of tongues and its mysterious nature (1 Cor 14:2). He made it a point to prompt the Corinthian church to seek more useful gifts, such as prophecy. While tongues edify the tongues-speaker (1 Cor 14:4) and serve to bless God and give thanks (1 Cor 14:16-17), prophecy convicts unbelievers of sin and inspires them to have faith in God (1 Cor 14:24-25). Paul's primary point of discussion was that all spiritual gifts should be handled with decency and order. His discussion of tongues prompted the famous verse: "If I speak in the tongues of men and of angels, but have not love, I am only a resounding gong or a clanging cymbal." (1 Corinthians 13:1) This leads some to presume that the speaking in tongues is often the expression of an angelic language or praise to God.

Church history

Twentieth-century Pentecostalism was not the earliest instance of "speaking in tongues" in church history after the events described in Acts and Paul's letters. Indeed, there were a number of recorded antecedents in several centuries of the Christian era, e.g.,

- 150 C.E. - Justin Martyr wrote âFor the prophetical gifts remain with us, even to this present time.â [1] and âNow, it is possible to see amongst us women and men who possess gifts of the Spirit of God.â [2]

- 156-172 - Montanus and his two prophetessesâMaximilla and Priscillaâspoke in tongues and saw this as evidence of the presence of the Holy Spirit. (Eusebius, Eccl. Hist. (17),Book 3).

- 175 C.E. - Irenaeus of Lyons, in his treatise Against Heresies, speaks positively of those in the church "who through the Spirit speak all kinds of languages." [3]

- circa 230 C.E. - Novatian said, âThis is He who places prophets in the Church, instructs teachers, directs tongues, gives powers and healings⊠and thus make the Lordâs Church everywhere, and in all, perfected and completed.â [4]

- circa 340 C.E. - Hilary of Poitiers, echoing Paul in 1 Corinthians, wrote, âFor God hath set same in the Church, first apostles⊠secondly prophets⊠thirdly teachers⊠next mighty works, among which are the healing of diseases⊠and gifts of either speaking or interpreting diverse kinds of tongues.â [5]

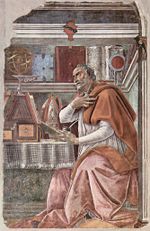

- circa 390 C.E. - Augustine of Hippo, in an exposition on Psalm 32, discusses a phenomenon contemporary to his time of those who "sing in jubilation," not in their own language, but in a manner that "may not be confined by the limits of syllables."[6].

- 475 - 1000 C.E. - During the so-called Dark Ages, little history was recorded although speaking in tongues may well have been practiced in certain times and places.

- 1100s - The heretical Waldenses and Albigenses, as well as certain of the orthodox Franciscans, all reportedly spoke in tongues. Saint Hildegard of Bingen is also reputed to have spoken and sung in tongues, and her spiritual songs were referred to by contemporaries as "concerts in the Spirit."

- 1300s - The Moravians are referred to by detractors as having spoken in tongues. John Roche, a contemporary critic, claimed that the Moravians "commonly broke into some disconnected jargon, which they often passed upon the vulgar, 'as the exuberant and resistless Evacuations of the Spirit.'"[7].

- 1600s - The Camisards also spoke sometimes in languages that were unknown: "Several persons of both sexes," James Du Bois of Montpellier recalled, "I have heard in their Extasies pronounce certain words, which seem'd to the Standers-by, to be some Foreign Language." These utterances were sometimes accompanied by the gift of interpretation.[8]

- 1600s - Early Quakers, such as Edward Burrough, make mention of tongues speaking in their meetings: "We spoke with new tongues, as the Lord gave us utterance, and His Spirit led us."[9].

- 1700s - John Wesley and Methodism. Wesleyan revivals across Europe and North America included many reportedly miraculous events, including speaking in tongues. [10]

- 1800s - Edward Irving and the Catholic Apostolic Church. Edward Irving, a minister in the Church of Scotland, wrote of a woman who would "speak at great length, and with superhuman strength, in an unknown tongue, to the great astonishment of all who heard."[11]. Irving further stated that "tongues are a great instrument for personal edification, however mysterious it may seem to us."

Contemporary Christians

Today, some Christians practice glossolalia as a part of their private devotions and some denominations of Christianity also accept and sometimes promote the use of glossolalia within corporate worship. This is particularly true within the Pentecostal and Charismatic traditions. Both Pentecostals and Charismatics believe that the ability to speak in tongues is a supernatural gift from God.

Pentecostals vary in their beliefs concerning the times appropriate for the practice of public glossolalia. First, there is the evidence of tongues at the baptism of the Holy Ghost - a direct personal experience with God. This is when a believer speaks in tongues when they are first baptized by the Holy Ghost. For some, this may be the only time an individual ever speaks in tongues, as there are a variety of other "gifts" or ministries into which the Holy Spirit may guide them (1 Cor 12:28). Secondly, there is the specific "gift of tongues." This is when a person is moved by God to speak in tongues during a church service or other Christian gathering for everyone to hear. The gift of tongues may be exercised anywhere; but many denominations believe that it must only be exercised when a person who has the gift of "interpretation of tongues" is present so that the message may be understood by the congregation (1 Cor 14:13, 27-28).

Within the Charismatic/Pentecostal tradition, theologians have also broken down glossolalia into three different manifestations. The "sign of tongues" refers to xenoglossy, wherein one speaks a foreign language he has never learned. The "giving of a tongue," on the other hand, refers to an unintelligible utterance by an individual believed to be inspired directly by the Holy Spirit and requiring a natural language interpretation if it is to be understood by others present. Lastly "praying (or singing) in the spirit" is typically used to refer to glossolalia as part of personal prayer (1 Cor 14:14). Many Pentecostals/Charismatics believe that all believers have the ability to speak in tongues as a form of prayer, based on 1 Cor. 14:14, Eph. 6:18, and Jude 20. Both "giving a tongue" and "praying in the spirit" are common features in contemporary Pentecostal and Charismatic church services.

Christians who practice glossolalia often describe their experience as a regular aspect of private prayer that tends to be associated with calm and pleasant emotions. Testifying to its freeing effects on the mind, proponents tell of how their native language flows easier following a prolonged session in prayer in tongues.[12] In other cases, tongues are accompanied by dramatic incidences such as being "slain in the spirit," in which practitioners become semi-conscious and may require the assistance of others to avoid injuring themselves during ecstatic convulsions.

The discussion regarding tongues has permeated many branches of the Christian Church, particularly since the widespread Charismatic Movement in the 1960s. Many books have been published either defending[13] or attacking[14] the practice.

Most churches fall into one of the following categories of the theological spectrum:

- Pentecostals - believe glossolalia is the initial evidence of receipt of the full baptism or blessing of the Holy Spirit

- Charismatics - believe glossolalia is not necessarily evidence of salvation or baptism of the Holy Spirit, but is edifying and encouraged

- Cessationalists and dispensationalists believe glossolalia is not evidence of salvation, neither is it any longer a sign of the blessing of the Holy Spirit, and that most or all authentic miraculous gifts ceased sometime after the close of the Apostolic Age.

Other religions

Aside from Christians, certain religious groups also have been observed to practice some form of glossolalia.

In the Old Testament, ecstatic prophecy was evident in the case of King Saul, who joined a group of prophets playing tambourines, flutes, and harps. The prophet Samuel predicted that: "The Spirit of the Lord will come upon you in power, and you will prophesy with them; and you will be changed into a different person." (1 Samuel 10:5-6)

Glossolalia is evident in the renowned ancient Oracle of Delphi, whereby a priestess of the Greek god Apollo (called a sibyl) spoke in unintelligible utterances, supposedly through the spirit of Apollo in her.

Certain Gnostic magical texts from the Roman period have written on them unintelligible syllables such "t t t t t t t t n n n n n n n n n d d d d d d d⊠," etc. It is believed that these may be transliterations of the sorts of sounds made during glossolalia. The Coptic Gospel of the Egyptians also features a hymn of (mostly) unintelligible syllables which is thought by some to be an early example of Christian glossolalia.

In the nineteenth century, Spiritists argued that some cases of unintelligible speech by trance mediums were actually cases of xenoglossy.

Glossolalia has also been observed in shamanism and the Voodoo religion of Haiti.

Scientific perspectives

Linguistics

The syllables that make up instances of glossolalia typically appear to be unpatterned reorganizations of phonemes from the primary language of the person uttering the syllables; thus, the glossolalia of people from Russia, the United Kingdom, and Brazil all sound quite different from each other, but vaguely resemble the Russian, English, and Portuguese languages, respectively. Many linguists generally regard most glossolalia as lacking any identifiable semantics, syntax, or morphology. [15]

Psychology

The attitude of modern psychology toward glossolalia has evolved from one of initial antagonismâviewing the phenomenon as a symptom of mental illnessâto a more objective stance in which speaking in tongues has sometimes been associated with beneficial effects. The first scientific study of glossolalia was done by psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin as part of his research into the linguistic behavior of schizophrenic patients. In 1927, G. B. Cutten published his book Speaking with tongues; historically and psychologically considered, which was regarded as a standard in medical literature for many years. Like Kraepelin, he linked glossolalia to schizophrenia and hysteria. In 1972, John Kildahl took a different psychological perspective in his book The Psychology of Speaking in Tongues. He stated that glossolalia was not necessarily a symptom of a mental illness and that glossolalists suffer less from stress than other people. He did observe, however, that glossolalists tend to have more need of authority figures and appeared to have had more crises in their lives.

A 2003 statistical study by the religious journal Pastoral Psychology concluded that, among the 991 male evangelical clergy sampled, glossolalia was associated with stable extraversion, and contrary to some theories, completely unrelated to psychopathology.[16]

In 2006, at the University of Pennsylvania, researchers, under the direction of Andrew Newberg, MD, completed the worldâs first brain-scan study of a group of individuals while they were speaking in tongues. During this study, researchers observed significant cerebral blood flow changes among individuals while exercising glossolalia. The study concluded that activity in the language centers of the brain actually decreased, while activity in the emotional centers of the brain increased.[17]

See also

Notes

- â Dialogue with Trypho, Chapter 82.

- â Ibid., Chapter 88.

- â Irenaeus. Adversus Haereses (Book V, Chapter 6) Against Heresies. (Book 2, Chapter 4.) www.newadvent.org. Retrieved October 22, 2007.

- â Treatise Concerning the Trinity Chapter, 29.

- â On the Trinity, Vol 8, Chap 33.

- â "On Psalm 32," Enarrationes in Psalmos, (32, ii, Sermo 1:8).

- â Stanley M. Burgess. "Medieval and Modern Western Churches," Initial Evidence, ed. Gary B. McGee (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 1991), 32.

- â John Lacy. "A Cry from the Desert." The Charismatic Movement. (London: Michael P. Hamilton, 1975), 32.; Hamilton, 75.

- â Edward Burrough. Epistle to the Reader, prefix to George Fox, "The Great Mystery of the Great Whore Unfolded and Antichrist's Kingdom Revealed Unto Destruction". (London: Thomas Simmons, (original 1659, ISBN 0404093531) Quaker Heritage Press online texts.

- â Daniel R. Jennings supernatural occurrences of John Wesley. www.answers.com. Retrieved October 20, 2007.

- â Edward Irving. "Facts Connected With Recent Manifestations of Spiritual Gifts." Frasers Magazine (Jan. 1832).

- â B. Grady and K. M. Loewenthal, (1997). "Features associated with speaking in tongues (glossolalia)." British Journal of Medical Psychology (70): 185-191.

- â Example:Laurence Christenson. Speaking in tongues: and its significance for the church. (Minneapolis, MN: Dimension Books, 1968).

- â Example:Robert Glenn Gromacki. The modern tongues movement. (Nutley, NJ: Presbyterian and Reformed Publishing Co., 1973, ISBN 0875523048) (Original 1967).

- â Glossolalia in Metareligion. www.meta-religion.com. Retrieved October 22, 2007.

- â L. J. Francis and M. Robbins. "Personality and Glossolalia: A Study Among Male Evangelical Clergy," Pastoral Psychology 51(5)(May 2003): 391-396 (6).

- â Andrew Newberg, Nancy Wintering and Donna Morgan. "Cerebral blood flow during the complex vocalization task of glossolalia." (Radiology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), J Nucl. Med. 47 (Supplement 1)(2006): 316P

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Burgess, Stanley M. "Medieval and Modern Western Churches." Initial Evidence, Edited by Gary B. McGee Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 1991. ISBN 0943575419

- Cartledge, Mark J., (ed.). Speaking in Tongues: Multi-Disciplinary Perspectives. Paternoster, 2006. ISBN 1842273779

- Christenson, Laurence. Speaking in tongues: and its significance for the church. Minneapolis, MNÂ : Dimension Books, 1968.

- Cutten, George B. Speaking with tongues; historically and psychologically considered. New Haven: Yale University Press; Kessinger Publishing, LLC., 2007 (original 1927). ISBN 978-0548126899

- Farrar, Frederic William. The Life and Work of St. Paul. New York: E.P. Dutton & Company, 1902.

- Francis, L. J. and M. Robbins. "Personality and Glossolalia: A Study Among Male Evangelical Clergy," Pastoral Psychology 51(5) (2003).

- Gromacki, Robert G. The modern tongues movement. Nutley, NJ: Presbyterian and Reformed Publishing Co., (original 1973) Baker Books, 1976. ISBN 978-0801037085

- Jennings, Daniel R. Supernatural Occurrences of John Wesley. Sean Multimedia. 2005.

- Justin Martyr and Michael Slusser Dialogue With Trypho (Selections from the Fathers of the Church) Catholic University of America Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0813213422

- Kennedy, Gerry and Rob Churchill. The Voynich Manuscript. London: Orion, 2004. ISBN 075285996X

- Kildahl, John. The Psychology of Speaking in Tongues. New York: Harper & Row, 1972.

- Lacy, John. "A Cry from the Desert" in The Charismatic Movement. London: Michael P. Hamilton, 1975 (original 1708). ISBN 0802834531

- Samarin, William J. "Variation and Variables in Religious Glossolalia," 121-130. Language in Society, Edited by Dell Haymes, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1972.

External links

All links retrieved May 23, 2024.

- Andrei Bely's Glossalolia {sic} with an English translation. community.middlebury.edu.

- A Skeptic's Perspective, The Skeptic's Dictionary on Glossolalia. skepdic.com.

- Catholic Encyclopedia: Gift of Tongues. www.newadvent.org.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.