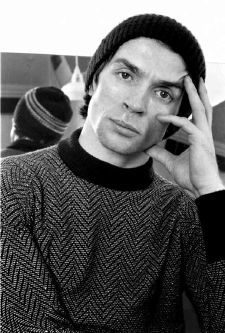

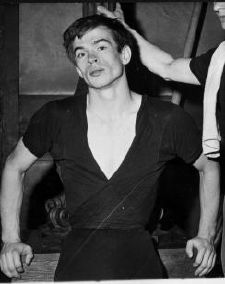

Rudolf Nureyev

Rudolf Nureyev (Tatar form Rudolf X√§m√§t ulńĪ Nuriev, Russian –†—É–ī–ĺ–Ľ—Ć—Ą –•–į–ľ–Ķ—ā–ĺ–≤–ł—á –Ě—É—Ä–ł–Ķ–≤) (March 17, 1938 ‚Äď January 6, 1993) is regarded as one of the greatest male dancers of the twentieth century, alongside Vaslav Nijinsky and Mikhail Baryshnikov. He captivated audiences with spectacular leaps and turns, while his passionate temperament and flamboyant behavior both on stage and off made him a cultural icon.

He showed early talent but got a late start with his advanced training. After graduating from ballet school in Leningrad, Nureyev bypassed the corps de ballet and immediately began dancing solo roles with the Kirov Ballet. He was soon recognized as one of the Soviet Union's greatest ballet stars.

On June 17, 1961, Nureyev eluded Soviet security guards while on tour with the Kirov in Paris and requested asylum. Using his newfound freedom during the following months, Nureyev performed in Paris, New York City, London, and Chicago. In 1962, he formed a partnership with the British Royal Ballet's acclaimed ballerina, Margot Fonteyn, who was 19 years his senior. Their opposite styles perfectly complimented each other, and they became a major force in the ballet world.

Nureyev was a "permanent guest artist" with the Royal Ballet for 20 years, while also attached to the Vienna State Opera as a dancer and chief of choreography. He was also much in demand as a guest artist around the world. In the 1970s, he also performed on television, in film, and on the Broadway stage. In 1989, he danced in the Soviet Union for the first time since his defection.

Nureyev died from AIDS in 1993, in Paris. His work did much to enhance the importance of the role of male dancers in ballet, and he pioneered the fusion of modern dance with classical ballet.

Early life and career at the Kirov

Nureyev was born 1938, on a train near Irkutsk, while his mother was traveling across Siberia to Vladivostok, where his father, a Red Army political commissar was stationed. Rudolf was raised in a Tatar family in a village near Ufa, in Soviet Bashkiria. As a child, he was encouraged to dance in Bashkir folk performances and his precocity was soon noticed.

Due to the disruption of Soviet cultural life caused by World War II, Nureyev was unable to enroll in a major ballet school until 1955, when he was sent to the the Leningrad Choreographic (Kirov) School, under Alexander Pushkin, with a stage debut at the Kirov Theater in Leningrad while a final-year student. Despite his late start, he was soon recognized as the most gifted dancer the school had seen for many years. Although an exceptional student, his rebellious temperament was already evident.

Nevertheless, within two years Nureyev was one of the Soviet Union's best-known dancers, in a country which revered the ballet and made national heroes of its best dancers. Soon, he enjoyed the rare privilege of travel outside the Soviet Union, when he danced in Vienna at the International Youth Festival. Not long after, however, he was told he would not be allowed to go abroad again. He was thus limited to tours of the Soviet provinces.

Defection to the West

In 1961, Nureyev's luck turned. The Kirov's leading male dancer, Konstantin Sergeyev, was injured, and at the last minute Nureyev was chosen to replace him on the Kirov's European tour. In Paris, his performances electrified audiences and critics. However, he broke the rules about mingling with foreigners, which alarmed the Kirov's management, and the KGB‚ÄĒwhich had been investigating him for some time for being a homosexual‚ÄĒreportedly wanted to send him back to the Soviet Union immediately.

Nureyev was told that he would not travel with the company to London because he was needed at home to dance at a special performance in the Kremlin. He correctly suspected that if he returned home he would likely be imprisoned. Thus, on June 17, 1961, at the Paris Airport, Rudolf Nureyev defected.

Within a week after defecting, Nureyev was signed up by the Grand Ballet du Marquis de Cuevas and was performing The Sleeping Beauty with Nina Vyroubova. Nureyev was an instant celebrity in the West. His dramatic defection, his outstanding technique, his good looks, and his astonishing charisma on stage made him an international star.

Nureyev's defection also gave him the personal freedom he had been denied in the Soviet Union. On a tour of Denmark he met Erik Bruhn, another dancer ten years his senior, who became his lover and protector for many years. Bruhn was director of the Royal Swedish Ballet from 1967 to 1972, and Artistic Director of the National Ballet of Canada from 1983 until his death in 1986. The relationship was a stormy one, for Nureyev was highly promiscuous.

Fonteyn and Nureyev

Nureyev's first appearance in England was at a ballet matinée organized by Margot Fonteyn in aid of The Royal Academy of Dancing, at which he danced Poeme Tragique, a heavily symbolic solo choreographed by Frederick Ashton, and brought the house to its feet in the Black Swan pas de deux from Swan Lake. He formed a partnership with Fonteyn which became perhaps the most famous in modern dance-theater history. Their first performance together was at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, in Giselle on February 21, 1962, when the applause of the audience lasted longer than the ballet itself.

Nureyev's fiery style perfectly complemented Fonteyn's refined elegance. Their long professional relationship would revive her career, while firmly establishing his. Together, Nureyev and Fonteyn forever transformed such cornerstone ballets as Swan Lake and Giselle. They also premiered Sir Frederick Ashton's ballet Marguerite and Armand, set to Liszt's B minor piano sonata, which became their signature piece. They inevitably filled the house. Films exist of their partnership in Les Sylphides, Swan Lake, Romeo and Juliet, and other roles.

Offstage, Fonteyn and Nureyev became lifelong friends, even after her retirement to Panama. Although their relationship was stormy, many who knew them said Fonteyn was the dearest person to Nureyev's heart, and Fonteyn in turn was especially loyal to Nureyev. When she was suffering from cancer, Nureyev paid many of her medical bills and visited her constantly despite his busy schedule.

In 1964, Nureyev went to the Vienna State Opera, where he remained as a dancer and chief of choreography until 1988. He remained as a "permanent guest artist" with the Royal Ballet for 20 years and was much in demand as a guest artist around the world.

Career as a non-dancer

Nureyev was in demand by film-makers early on in his career in the West. In 1962, he made his screen debut in a film version of Les Sylphides. In 1977, he played Rudolph Valentino in Ken Russell's Valentino. However, he had neither the talent nor the temperament for a serious acting career. He branched into modern dance with the Dutch National Ballet in 1968. In 1972, Robert Helpmann invited him to tour Australia with his own production of Don Quixote, his directorial debut. In 1973, a gala world premiere for the movie version was held at the Sydney Opera House.

During the 1970s, Nureyev appeared in several movies and toured the United States in a revival of the Broadway musical The King and I. His guest appearance on the then-struggling television series The Muppet Show is credited for boosting the series to worldwide success. In 1982, he became a naturalized Austrian. In 1983, he was appointed director of the Paris Opera Ballet, where as well as directing he continued to dance and to promote younger dancers. Among the dancers he groomed to stardom were Sylvie Guillem, Isabel Guerin, Manuel Legris, Elisabeth Maurin, Elisabeth Platel, Charles Jude, and Monique Loudieres. Despite an advancing illness towards the end of his tenure, he worked tirelessly, staging new versions of old standbys and commissioning some of the most groundbreaking choreographic works of his time. His own Romeo and Juliet, set in Hollywood, was a popular success.

Final years

When AIDS appeared in France in about 1982, Nureyev, like many homosexual men, took little notice. He presumably contracted HIV at some point in the early 1980s. For several years, he simply denied that anything was wrong with his health.

Although he petitioned the Soviet government for many years to be allowed to visit his mother, with whom he remained very close, Nureyev was not allowed to do so until 1989, when she was dying and Mikhail Gorbachev consented to the visit. During this trip, Nureyev was invited to dance once again with the Kirov Ballet at the Maryinsky theater in Leningrad. Sadly, it was too late; he was too old and too sick, and his performance was disappointing. Nonetheless, the visit gave him the opportunity to see many of the teachers and colleagues he had not seen since he defected, including his first ballet teacher in Ufa, where his mother lived.

When, in about 1990, he became undeniably ill, he continued to deny that he had AIDS, insisting that he had several other ailments. He tried several experimental treatments, but they did not stop the inevitable decline of his body. Toward the end of his life, as dancing became more and more agonizing for him, Nureyev resigned himself to small, non-dancing roles. At the urging of Fonteyn, he had a short but successful conducting career, which was unfortunately cut short due to his declining health.

Finally, he had to face the fact that he was dying. He won back the admiration of many of his detractors by his courage during this period. The loss of his looks pained him, but he continued to struggle through public appearances. At his last appearance, at a 1992 production of La Bayadère at the Palais Garnier, Nureyev received an emotional standing ovation from the audience.

Nureyev died in Paris, France, a few months later, aged 54. His grave, at Sainte-Geneviève-des-Bois near Paris, is as spectacular as his stage performances: A Russian carpet thrown carelessly over it, turning out on close examination to be of mosaic.

Legacy

Nureyev's influence on the world of ballet changed the perception of male dancers. In his own productions of the classics he emphasized male roles more than earlier productions had done, setting a precedent that has been followed by many choreographers ever since.

He was also the first dancer to cross the borders between classical ballet and modern dance by dancing both genres, having been trained as a classical dancer. He received considerable criticism in his day for his experimentation with modern dance. Today, as a result of his pioneering efforts, it is quite normal for dancers to get training in both styles.

His act of defecting from the Soviet Union, too, established a precedent; and many other famous dancers would follow his example.

In 1992, he was recipient of France's highest cultural award, the Chevalier de l'Ordre des Arts et Lettres. In 1987, received the Capezio Dance Award.

Nureyev is regarded as one of the greatest male dancers of the twentieth century.

Nureyev's choreographies

- La Bayadere Acte III‚ÄĒOctober 3, 1974‚ÄĒAfter Petipa

- Manfred‚ÄĒNovember 20, 1979‚ÄĒOriginal choreography

- Don Quichotte‚ÄĒMarch 6, 1981‚ÄĒAfter Petipa

- Raymonda‚ÄĒNovember 5, 1983‚ÄĒAfter Petipa

- Le Lac des Cygnes‚ÄĒDecember 20, 1984‚ÄĒAfter Sergueev and Bourmeister

- Romeo et Juliette‚ÄĒOctober 19, 1984‚ÄĒOriginal choreography

- The Tempest‚ÄĒMarch 9, 1984‚ÄĒOriginal choreography

- Bach Suite‚ÄĒApril 16, 1984‚ÄĒAvec Francine Lancelot

- Casse Noisette‚ÄĒDecember 20, 1985‚ÄĒAfter Petipa

- Washington Square‚ÄĒJune 25, 1985‚ÄĒOriginal choreography

- Cendrillon‚ÄĒOctober 24, 1986‚ÄĒOriginal choreography

- La Belle au Bois Dormant‚ÄĒMarch 18, 1989‚ÄĒAfter Petipa

- La Bayadere‚ÄĒOctober 8, 1992‚ÄĒAfter Petipa

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bland, Alexander. Nureyev: An Autobiography with Pictures. E.P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1963.

- Bland, Alexander, The Nureyev Valentino: Portrait of a Film. Cassell & Collier Macmillan Publishers, 1977. ISBN 978-0289707968

- Maybarduk, Linda. The Dancer Who Flew: A Memoir of Rudolf Nureyev. Tundra Books, 1999. ISBN 978-0887764158

- Percival, John, Nureyev: Aspects of the Dancer. Putnam, 1975. ISBN 978-0399115448

- Solway, Diane. Nureyev: His Life. Quill, 1999. ISBN 978-0688172206

External links

All links retrieved December 22, 2022.

- Rudolf Nureyev Foundation. www.nureyev.org.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.