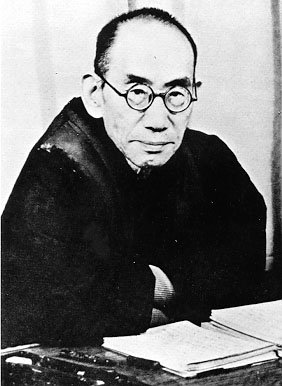

Nishida Kitaro

Nishida Kitaro (Ť•ŅÁĒį ŚĻ匧öťÉé, Nishida KitarŇć') (1870 ‚Äď 1945) was a prominent Japanese philosopher of the Meiji era. Nishida Kitaro engaged in an effort to translate Eastern philosophy, especially Zen Buddhism, into Western philosophical concepts. He worked in an environment of contradiction between traditional Japanese culture and the influx of Western materialism, industrialism, philosophy and Christianity, and a difficult personal life. For the first time in modern Japanese philosophical history, Nishida successfully formulated a highly original and distinctive philosophy which had a significant influence on many intellectuals of the modern period. Nishida founded what has been called the Kyoto School of philosophy. The Kyoto School has produced many unique philosophers, including Tanabe Hajime and Nishitani Keiji. Nishida, like his close friend D.T. Suzuki, developed a unique system of thought by assimilating Western philosophy into the traditions of Far Eastern thought, and in particular of Zen Buddhism.

Life

Early Life

Nishida Kitaro was born on June 17, 1870, in the Mori section of Unoke, a farming village on the Sea of Japan, about twenty miles from Kanazawa, the capital of Ishikawa prefecture. He was the eldest son and the third of five children. His family, which had held the powerful position of the village head during the Tokugawa era, were wealthy land owners. His father, Yasunori, was not only wealthy but also dedicated to education. In 1875 his father opened an elementary school in a temple and also became a teacher. He enrolled Kitaro in the school. Four years later his father officially started an elementary school in his house, which is the present-day Unoke Elementary School. After graduating from elementary school in 1883, Kitaro entered the Ishikawa Normal School in Kanazawa. Around that time his parent became estranged and his father became bankrupt when his business failed. Kitaro became ill with typhoid and had to leave school.

In July 1886, he entered the middle school attached to the Ishikawa Prefecture College. In July 1889, Nishida Kitaro was admitted to the Fourth Higher School. Nishida lived in the home of Hojyo Tokiyoshi, who taught him mathematics and English. At this school Nishida met his lifelong friend, D.T. Suzuki, who later became a world famous scholar of Zen Buddhism, and Yamamoto Ryokichi. The school was moved from local jurisdiction to the Ministry of Education, and the warm and friendly atmosphere of the school changed to one where the students were subjected to rules and regulations on all sides.

Despite Hojyo’s efforts to persuade him to become a mathematician, Nishida took an interest in Zen Buddhism and began to specialize in philosophy. He left the Fourth Higher School just before his graduation in 1890. Until 1893 Nishida studied in Tokyo Imperial University as a special student. Even though he was studying philosophy, he was discriminated against because of his status as a special student. Regular students could freely use the library and school facilities, but a special student was under restrictions in every area of the university. After graduation, his irregular background made it difficult for him to find a job.

Teaching Career

He taught briefly at the middle school of a local village in Ishikawa prefecture, where he married Tokuda Kotomi, the daughther of Tokuda Ko, in May of 1895. (Together, Nishida and Kotomi had eight children; six daughters and two sons.) In 1896 he secured a position teaching German at the Fourth Higher School in Kanazawa, but was dismissed because of internecine strife. Around this period his wife divorced him temporarily, and he became obsessed with Zen Buddhism. The same year his former teacher, Hojyo Tokiyoshi, who was now the principal of the Yamaguchi Higher School, invited Nishida to be a teacher. In 1899, Hojyo Tokiyoshi became principal of the Fourth Higher School, and again invited Nishida there to teach psychology, ethics, German, and logic. He taught there for ten years, during which he conducted researches in philosophy. Nishida ambitiously organized a student reading circle that read Goethe’s Faust and Dante’s Inferno and invited lectures from various religious sects and denominations. He was like a father who always looked after his students, an attitude which later led him to found a philosophical scholars group, Kyoto Gakuha (Kyoto School).

After Hojyo was transferred from the Fourth Higher School back to the Yamaguchi Higher School, Nishida found himself incompatible with the new principal. For several years Nishida led an ill-fated private life. His brother was killed on the battlefield in 1904. In January of 1907, Nishida’s daughter Yuko died of bronchitis and in June of the same year, another daughter, only one month old, died. Nishida himself became ill with pleurisy. He overcame his personal tragedies and devoted himself to research and increasing the level of his intellectual and academic output. In 1909 he was appointed a professor of German at Gakushuin University in Tokyo.

‚ÄúAn Inquiry Into the Good‚ÄĚ

In January of 1911, Nishida published An Inquiry Into the Good, the fruit of his philosophical studies. The general public welcomed the book, even though it was filled with difficult philosophical terms. Although he was inspired by American philosopher William James and French philosopher Henri Bergson, Nishida developed an original concept, ‚Äúpure experience.‚ÄĚ Nishida defines ‚Äúpure experience‚ÄĚ as direct experience without deliberative discrimination. After the Meiji Restoration, Western culture and Western concepts were flooding into Japan, and people were urgently trying to understand and absorb them. In the academic world Nishida created an original unique philosophy that provided a Western philosophical framework for Zen experience.

In 1910 Nishida was appointed assistant professor of ethics at Kyoto Imperial University; in 1914 he was nominated to the first chair of History of Philosophy and taught until his retirement in 1928.

Maturity

Even after developing the concept of ‚Äúpure experience,‚ÄĚ Nishida never satisfied with this concept and continued his research. Influenced by Henri Bergson and the German Neo-Kantians, he discovered a deeper significance in it and elevated the concept of ‚Äúpure experience‚ÄĚ to a higher level. In his second book Intuition and Reflection in Self-Consciousness, Nishida developed the metaphysical concept of jikaku, meaning ‚Äúself-awakening.‚ÄĚ He identified this self-awakening with the state of the ‚Äúabsolute free will.‚ÄĚ

In 1918 another wave of the tragedy struck Nishida‚Äôs family. Nishida‚Äôs mother died in 1918, the next year his wife, Kotomi, suffered a brain hemorrhage, and in 1920 Nishida‚Äôs eldest son, Ken, died of peritonitis at the age of twenty-two. Soon three more of his daughters fell ill with typhus. In 1925 his wife, Kotomi, 50 years old, died after a long period of suffering. In spite of the tragedy and personal suffering, Nishida continued to conduct his philosophical research. In 1926, as Nishida developed the concepts of ‚Äúpure experience‚ÄĚ and ‚Äúabsolute free will,‚ÄĚ he offered the important concept of ‚Äúplace.‚ÄĚ The next year the epoch-making concept of Hataraku mono kara miru mono e (from that which acts to that which is seen) gave form to the idea of basho no ronri (logic of place).

In 1928 Nishida left his position as professor at Kyoto University, and in the same year his first grandchild was born. He married his second wife, Koto, in 1931. In 1940, during his retirement, he was awarded the Cultural Medal of Honor. Nishida Kitaro died at the age of seventy-five of a renal infection. His grave is located at Reiun'in, a temple in the Myoshin-ji compound in Kyoto.

Philosophical Background

The Sakoku (literally "country in chains" or "lock up of country") of the Tokugawa Shogunate was a policy of national isolation which closed the door to foreigners and forbade Japanese people to travel abroad. This isolation began in 1641 and lasted for 212 years. During these years Christianity and all foreign books were strictly controlled. Only Dutch translators in Nagasaki were allowed, under careful supervision.

On July 8, 1853, the four American Navy ships of Commodore Matthew C. Perry sailed into the Bay of Edo (Tokyo). Commodore Perry insisted on landing and delivering a message for the Emperor from American President Millard Fillmore. The Japanese, who were aware of the power of the American naval guns, allowed the message to be delivered. It demanded that Japan open certain ports to trade with the West. The four ships, USS Mississippi, USS Plymouth, USS Saratoga, and USS Susquehanna, became known as the kurofune, the Black Ships.

Nishida Kitaro was born in 1868, the same year in which the Tokugawa Shogunate ended and the Meiji era began. He grew up under the strong influence of Western civilization and its conflict with the indigenous traditions that were resisting this new wave. Western culture, especially materialism and industrialization, began to flood over Japan as though a dam had broken. The Japanese government responded to the foreign influx with a thin veneer of policy and culture. Foreign Minister Kaoru Inoue built a special guest house (rokumeikan) where foreign VIPs were welcomed as guests with balls and receptions. Many intellectuals, especially the youth, were not able to keep in step with this trend. For Japanese people, Western thought seemed like an alienation from tradition, especially from the nature-centered thinking of Buddhism and Shintoism. Young Nishida experienced and tackled the philosophical chaos of this era.

The Formation of Nishida’s Philosophy

Having been born in the third year of the Meiji Era, Nishida was presented with a newly unique opportunity to contemplate Eastern philosophical issues in the fresh light of Western philosophy. Nishida's original and creative philosophy, incorporating the ideas of both Zen and Western philosophy, was aimed at bringing the East and West closer together. Throughout his lifetime, Nishida published a number of books and essays including An Inquiry into the Good, and The Logic of the Place of Nothingness and the Religious Worldview. Nishida‚Äôs life work was the foundation for the Kyoto School of Philosophy and the inspiration for the original thinking of his disciples. The most famous concept in Nishida's philosophy is the logic of basho (Japanese: Ś†īśČÄ; place or topos).

Like the existentialists, Nishida developed his thought through his personal sufferings. He experienced many serious domestic tragedies during his life. In his diary, at the age of 33, Nishida wrote, ‚ÄúI do Zen meditation not for academic reasons but for my heart (mind) and my life,‚ÄĚ and on another day, ‚Äúlearning is, after all, for the purpose of living, life is most important, learning without the life has no meaning.‚ÄĚ For a period of six years starting at the age of 28, his diary recorded the Zen meditation he did in the morning, afternoon and evening. It is interesting that Nishida never categorized Zen meditation as religion. People later called his philosophy, Nishida tetsugaku (philosophy) which was a reflection of his life of adversity. Metaphorically speaking, many times he was thrown down from one of life's cliffs and had to crawl up again from the bottom of the valley. Sometimes he lost his ‚Äútrue self‚ÄĚ and had to search for it. His philosophical theory was, in a sense, the result of his life-struggle.

There were many types of ‚Äúdespair‚ÄĚ and ‚Äúalienation‚ÄĚ during the Meiji era. Nishida‚Äôs philosophical struggle was affected not only by these social contradictions but also by his domestic situation. Just as S√łren Kierkegaard was influenced by his father, Michael Pedersen Kierkegaard, young Nishida‚Äôs way of thinking was affected by his father, Nishida Yasunori. His father, Yasunori, was an educator, but he kept mistresses. Before his marriage to Nishida‚Äôs mother, Tosa, he had an illegitimate child, and his behavior disgusted the local villagers. Yasunori was finally obliged to leave his house and lands because of financial difficulties. It was said that the bright and laughing Nishida gradually became a gloomy and pessimistic child. His friends and teachers often remarked on his odd silences; sometimes he sat all night with Hojyo Tokiyuki without saying anything.

Characteristics of Nishida’s Philosophy

Nishida attempted to explicate a kind of experience, which he called ‚Äúpure experience,‚ÄĚ prior to conceptual articulation. Zen, as well as other Far Eastern thoughts, conceives ‚Äúexperience‚ÄĚ and ‚Äúunderstanding‚ÄĚ as a holistic, embodied experience or awakening prior to conceptual articulations by means of sets of dualistic categories such as subject-object, part-whole, intuition-reflection, particular-universal, and relative-absolute. Those experiences often reject linguistic articulation. Nishida attempted to explicate pre-conceptual, pre-linguistic experiences, rooted in Zen, and find the relationships between those experiences and conceptualized thoughts. Nishida employed categories and concepts of Western philosophy in order to explain the relationships between these two modes of thought. Nishida‚Äôs philosophy is one of the earliest attempts to explore two distinct modes of thinking; the pre-conceptual and the conceptual, the non-linguistic and the linguistic. Later Nishida attempted to re-formulate his thought within the framework of a topology he developed.

Notable members of the Kyoto School

- Tanabe Hajime

- Nishitani Keiji

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

Works by Nishida

- Nishida, Kitaro, Masao Abe, and Christopher Ives (trans.). An Inquiry Into the Good. Yale University Press, 1992. ISBN 0300052332

- Nishida, Kitaro, and David Dilworth (trans.). Last Writings. University of Hawaii Press, 1993. ISBN 0824815548

Secondary sources

- Carter, Robert E. The Nothingness Beyond God: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Nishida Kitaro. St. Paul, MN: Paragon House, 1997. ISBN 1557787611

- Heisig, James. Philosophers of Nothingness. University of Hawaii Press, 2001. ISBN 0824824814

- Nishitano, Keiji. Religion and Nothingness. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1983. ISBN 0520073649

- Wargo, Robert J. The Logic Of Nothingness: A Study Of Nishida Kitaro. University of Hawaii Press, 2005. ISBN 0824829697

- Yusa, Michiko. Zen & Philosophy: An Intellectual Biography of Nishida Kitaro. University of Hawaii Press, 1992. ISBN 0824824598

External links

All links retrieved November 15, 2022.

General Philosophy Sources

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Paideia Project Online

- The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Project Gutenberg

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.