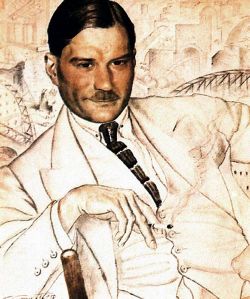

Evgeny Zamyatin

Yevgeny Ivanovich Zamyatin (–ē–≤–≥–ĶŐĀ–Ĺ–ł–Ļ –ė–≤–įŐĀ–Ĺ–ĺ–≤–ł—á –ó–į–ľ—ŹŐĀ—ā–ł–Ĺ sometimes translated into English as Eugene Zamyatin) (February 1, 1884 ‚Äď March 10, 1937) was a Russian author, most famous for his novel We, a story of dystopian future which influenced George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four and Aldous Huxley's Brave New World.

Zamyatin also wrote a number of short stories, in fairy tale form, that constituted satirical criticism of the Communist regime in Russia. While he was initially a supporter of the regime, the hopes of Zamyatin and many of his fellow socialists were not realized by the new government. Zamyatin turned to his literature in order to register his protest. He used the dystopian novel to demonstrate the difference between the glowing promises of ideology and its bitter practice.

Biography

Zamyatin was born in Lebedian, Russia, two hundred miles south of Moscow. His father was a Russian Orthodox priest and schoolmaster and his mother a musician. He studied naval engineering in St. Petersburg from 1902 until 1908, during which time he joined the Bolsheviks. He was arrested during the Russian Revolution of 1905 and exiled, but returned to St. Petersburg, where he lived illegally before moving to Finland in 1906, to finish his studies. Returning to Russia he began to write fiction as a hobby. He was arrested and exiled a second time in 1911, but amnestied in 1913. His Ujezdnoje (A Provincial Tale) in 1913, which satirized life in a small Russian town, brought him a degree of fame. The next year he was tried for maligning the military in his story Na Kulichkakh. He continued to contribute articles to various socialist newspapers.

After graduating as a naval engineer, he worked professionally at home and abroad. In 1916, he was sent to England to supervise the construction of icebreakers at the shipyards in Walker, Newcastle upon Tyne and Wallsend. He wrote The Islanders satirizing English life, and its pendant, A Fisher of Men, both published after his return to Russia in late 1917.

After the Russian Revolution of 1917 he edited several journals, lectured on writing and edited Russian translations of works by Jack London, O. Henry, H. G. Wells and others.

Zamyatin supported the October Revolution, but opposed the system of censorship under the Bolsheviks. His works were increasingly critical of the regime. He boldly stated: "True literature can only exist when it is created, not by diligent and reliable officials, but by madmen, hermits, heretics, dreamers, rebels and skeptics." This attitude caused his position to become increasingly difficult as the 1920s wore on. Ultimately, his works were banned and he wasn't permitted to publish, particularly after the publication of We in a Russian emigré journal in 1927.

Zamyatin was eventually given permission to leave Russia by Stalin in 1931, after the intercession of Gorki. He settled in Paris, with his wife, where he died in poverty of a heart attack in 1937.

He is buried in Thiais, just south of Paris. Ironically, the cemetery of his final resting place is on Rue de Stalingrad.

We

We (–ú—č, written 1920-1921, English translation 1924) is Zamyatin's most famous and important work. The title is the Russian first person plural personal pronoun, transliterated phonetically as "Mwe." It was written in response to the author's personal experiences with the Russian revolutions of 1905 and 1917, as well as his life in the Newcastle suburb of Jesmond, working in the Tyne shipyards at nearby Wallsend during the First World War. It was at Tyneside that he observed the rationalization of labor on a large scale.

History and influence

The novel was the first work banned by Glavlit, or the Main Administration for Safeguarding State Secrets in the Press, the new Soviet censorship bureau, in 1921, though the initial draft dates to 1919. In fact, a good deal of the basis of the novel is present in Zamyatin's novella Islanders, begun in Newcastle in 1916. Zamyatin's literary position deteriorated throughout the 1920s, and he was eventually allowed to emigrate to Paris in 1931, probably after the intercession of Maxim Gorky.

The novel was first published in English in 1924, but the first publication in Russia had to wait until 1988, when it appeared alongside George Orwell's 1984. Orwell was familiar with We, having read it in French, reviewing it in 1946; it influenced his Nineteen Eighty-Four. Aldous Huxley reportedly claimed that he did not read We before writing Brave New World, although Orwell himself believed that Huxley was lying.

Plot summary

The story is told by the protagonist, "D-503," in his diary, which details both his work as a mathematician and his misadventures with a resistance group called the Mephi, who take their name from Mephistopheles. He has started a diary as a testament to the happiness that One State has discovered, hoping to present it to the extraterrestrial civilizations which The Integral, the spaceship he designed, will visit. However, as the novel progresses, his infatuation with I-330, a rebellious woman in league with Mephi, starts to take over his life. He starts to lose his initial dedication to the utopian One State, and his distinction between reality and dreams starts to fade. By the end of his story, he has almost been driven to madness by inner conflicts between himself and his society, or imagination and mathematic truths.

Utopian Society

The Utopian Society depicted in We is called One State, a glass city led by the Benefactor (in some translations also known as The Well Doer) and surrounded by a giant Green Wall to separate the citizens from nature. The story takes place after the Two Hundred Year's War, a war that wiped out all but 0.2 percent of Earth's population. The 200 Years War was a war over a rare substance never mentioned in the book, as all knowledge of the war comes from biblical metaphors; the objective of the war was a rare substance called "bread" as the "Christians gladiated over it"‚ÄĒas in countries fighting conventional wars. However, it is also revealed that the war only ended after the use of superweapons, after which came a time when grass grew over old streets and buildings crumbled.

All human activities are reduced to mathematical equations, or at least attempted to. For sexual intercourse, numbers (people) receive a booklet of pink coupons which they fill out with the other number they'd like to use on a certain day. Intercourse is the only time shades are allowed to be lowered. It's believed pink coupons eliminate envy.

Every single moment in one's life is directed by "The Table," a precursor to 1984's telescreen. It is in every single residence, and directs their every waking instant. With it, every person eats the same way at the same time, wakes at the exact same time, goes to sleep at the exact same time, and works at the exact same time. The only exception are two required "Free Hours" in which a Number might go out and stroll down a street, or work, or write a diary or the like. According to D-503, he is proud to think that someday there will be a society in which the Free Hours have been eliminated, and every single moment is catalogued and choreographed.

Society places no value on the individual. Names are replaced by numbers. In one instance, ten numbers are incinerated while standing too close to the rockets of the Integral during tests. With pride, D-503 writes that this did not slow down the test in any way.

The Benefactor is the equivalent of Big Brother, but unlike his Orwellian equivalent, the Benefactor is actually confirmed to exist when D-503 has an encounter with him. An "election" is held every year on Unanimity Day, but the outcome is always known beforehand, with the Benefactor unanimously being reelected each year.

Allusions/references to other works

The numbers of the main characters‚ÄĒO-90, D-503 and I-330‚ÄĒare almost certainly derived from the specification of the Saint Alexander Nevsky, Zamyatin's favorite icebreaker, whose drawings he claimed to have signed with his own special stamp. However, other interpretations have been put forward, including one suggestion that the numbers are a Bible code.

The names are also related to characters' genders. Males' names begin with consonants and end with odd numbers, females' with vowels and even numbers.

Additionally, the letters corresponding with the numbers are directly related to various characteristics of that specific character. For example, the character O-90, D-503's most common sexual partner and female friend in the beginning portion of the novel, has very round and simple physical and mental characteristics. Such relationships between name letter and character exist throughout the entirety of the novel.

Furthermore, in the novel, D-503 mentions how the irrationality of square root -1 bothers him greatly. It is known that in math, this number is represented by the letter i. But, the most ironic and one of the greatest satirical symbols in the novel is the fact that One State thinks it is perfect because it bases its system on math even though math itself has irrationality in it. The point that Zamyatin tries to get across to the Communist leaders is that it is impossible to remove all the rebels against a system and he even says this through (ironically) I-330: "There is no one final revolution. Revolutions are infinite."

References to Mephistopheles are allusions to Satan and his rebellion against Heaven in the Bible. The Mephi are rebels against what is considered to be a perfect society. The novel itself could also be considered a criticism of organized religion given this interpretation.

Literary significance & criticism

We is a futuristic dystopian satire, generally considered to be the grandfather of the genre. It takes the totalitarian and conformative aspects of modern industrial society to an extreme conclusion, depicting a state that believes that free will is the cause of unhappiness, and that citizens' lives should be controlled with mathematical precision based on the system of industrial efficiency created by Frederick Winslow Taylor. Among many other literary innovations, Zamyatin's futuristic vision includes houses, and indeed everything else, made of glass or other transparent materials, so that everyone is constantly visible. Zamyatin was very critical of communism in Russia and his work was repeatedly banned.

Release details

English translations include:

- 1924, UK ?, unknown publisher (ISBN N/A), 1924, hardback (First edition, Eng. trans. by Gregory Ziboorg)

- 1972, USA, Viking Press (ISBN 0670753181), 1972 (Eng. trans. Mirra Ginsburg)

- 1972, UK, Penguin Books (ISBN 0140035109), 1972, paperback (Eng. trans. Bernard Guilbert Guerney)

- 1993, UK, Penguin Books (ISBN 0140185852), November 1993, paperback (Eng. trans. Clarence Brown)

- 1995, USA, Penguin Books (ISBN 0525470395), 1995, paperback (Eng. trans. by Gregory Ziboorg)

- 2001, USA, Rebound by Sagebrush (ISBN 0613178750), 2001, hardback (Library ed. Eng. trans by Mirra Ginsburg)

- 2006, USA, Random House (ISBN 081297462X), 2006, paperback (Eng. trans. by Natasha Randall)

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Joshua Glenn. "In a perfect world", The Boston Globe, July 23, 2006.

- Fischer, Peter A. (Autumn 1971). Review of The Life and Works of Evgenij Zamjatin by Alex M. Shane. Slavic and East European Journal 15 (3): 388-390.

- Myers, Alan (1990). Evgenii Zamiatin in Newcastle. The Slavonic and East European Review 68 (1): 91-99.

- Shane, Alex M. (1968). The Life and Works of Evgenij Zamjatin. University of California Press.

- Zamyatin, Yevgeny (1994). A Soviet Heretic: Essays, Mirra Ginsburg (editor and translator), Quartet Books Ltd. ISBN 0226978656

External links

All links retrieved March 23, 2024.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.