Cognitive therapy

- This article is about Aaron Beck's cognitive therapy. For the superordinate school of psychotherapy, see Cognitive behavioral therapy.

Cognitive therapy (CT) is a type of psychotherapy developed by American psychiatrist Aaron T. Beck in the 1960s. CT is one therapeutic approach within the larger group of cognitive behavioral therapies (CBT).

Cognitive therapy is based on the cognitive model, which states that thoughts, feelings, and behavior are all connected. Thus, individuals can move toward overcoming difficulties and meeting their goals by identifying and changing unhelpful or inaccurate thinking, problematic behavior, and distressing emotional responses. This therapy involves the individual working with the therapist to develop skills for testing and changing beliefs, identifying distorted thinking, relating to others in different ways, and changing behaviors.

History

Precursors of certain aspects of cognitive therapy have been identified in various ancient philosophical traditions, particularly Stoicism.[1] For example, Beck's original treatment manual for depression states, "The philosophical origins of cognitive therapy can be traced back to the Stoic philosophers."[2]

One of the first therapists to address cognition in psychotherapy was Alfred Adler, notably with his idea of "basic mistakes" and how they contributed to the creation of unhealthy behavioral and life goals.[3] Abraham Low believed that someone's thoughts were best changed by changing their actions: the patient must learn to ‚Äúmove his muscles to reeducate the brain.‚ÄĚ[4] Adler and Low influenced the work of Albert Ellis, who worked on cognitive treatment methods in the 1950s. He called his approach Rational Therapy (RT) at first, then Rational Emotive Therapy (RET) and later Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (REBT). The first version of REBT was announced to the public in 1956.[3]

In the late 1950s Aaron T. Beck became disillusioned with long-term psychodynamic approaches based on gaining insight into unconscious emotions. He came to the conclusion that the way in which his patients perceived and attributed meaning in their daily lives was a key to therapy. This key lies not deep in the unconscious, but in "thinking problems" that are much closer to conscious awareness. He found that his patients engaged in an endless self-deprecating monologue, telling them that they were worthless and would never succeed. He called these "automatic thoughts," which when repeated many times became the patient's reality and led them to behave in self-defeating ways.[5]

Beck outlined his approach in Depression: Causes and Treatment in 1967.[6] He later expanded his focus to include anxiety disorders, in Cognitive Therapy and the Emotional Disorders in 1975,[7] and later to other disorders. He also introduced a focus on the underlying "schema"‚ÄĒthe underlying ways in which people process information about the self, the world, or the future.

This new cognitive approach came into conflict with the behaviorism common at the time, which claimed that talk of mental causes was not scientific or meaningful, and that assessing stimuli and behavioral responses was the best way to practice psychology. However, the 1970s saw a general "cognitive revolution" in psychology. Behavioral modification techniques and cognitive therapy techniques became joined, giving rise to a common concept of cognitive behavioral therapy. Although cognitive therapy has often included some behavioral components, advocates of Beck's particular approach sought to maintain and establish its integrity as a distinct, standardized form of cognitive behavioral therapy in which the cognitive shift is the key mechanism of change.[8]

Aaron and his daughter Judith S. Beck founded the Beck Institute for Cognitive Therapy and Research in 1994. This was later renamed the "Beck Institute for Cognitive Behavior Therapy."[9] In 1995, Judith released Cognitive Therapy: Basics and Beyond, a treatment manual endorsed by her father Aaron.[10] Later editions, also endorsed by her father, are called Cognitive Behavior Therapy: Basics and Beyond. [11]

As cognitive therapy continued to grow in popularity, the non-profit "Academy of Cognitive Therapy" was created in 1998 to accredit cognitive therapists, create a forum for members to share research and interventions, and to educate the public about cognitive therapy and related mental health issues. The academy later changed its name to the "Academy of Cognitive and Behavioral Therapies."[12]

Cognitive model

The cognitive model was originally constructed following research studies conducted by Aaron Beck to explain the psychological processes in depression. It divides beliefs into three levels:[11]

- Automatic thought

- Intermediate belief

- Core belief or basic belief

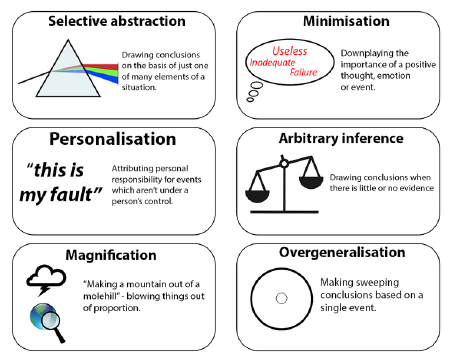

Therapy consists of testing the assumptions which one makes and looking for new information that could help shift the assumptions in a way that leads to different emotional or behavioral reactions. Change may begin by targeting thoughts (to change emotion and behavior), behavior (to change feelings and thoughts), or the individual's goals (by identifying thoughts, feelings or behavior that conflict with the goals). Beck initially focused on depression and developed a list of "errors" (cognitive distortion) in thinking that he proposed could maintain depression, including arbitrary inference, selective abstraction, overgeneralization, and magnification (of negatives) and minimization (of positives).

As an example of how CT might work: Having made a mistake at work, a man may believe: "I'm useless and can't do anything right at work." He may then focus on the mistake (which he takes as evidence that his belief is true), and his thoughts about being "useless" are likely to lead to negative emotion (frustration, sadness, hopelessness). Given these thoughts and feelings, he may then begin to avoid challenges at work, which is behavior that could provide even more evidence for him that his belief is true. As a result, any adaptive response and further constructive consequences become unlikely, and he may focus even more on any mistakes he may make, which serve to reinforce the original belief of being "useless." In therapy, this example could be identified as a self-fulfilling prophecy or "problem cycle," and the efforts of the therapist and patient would be directed at working together to explore and change this cycle.

People who are working with a cognitive therapist often practice more flexible ways to think and respond, learning to ask themselves whether their thoughts are completely true, and whether those thoughts are helping them to meet their goals. Thoughts that do not meet this description may then be shifted to something more accurate or helpful, leading to more positive emotion, more desirable behavior, and movement toward the person's goals. Cognitive therapy takes a skill-building approach, where the therapist helps the person to learn and practice these skills independently, eventually "becoming their own therapist."

Cognitive restructuring

Cognitive restructuring involves four steps:[13]

- Identification of problematic cognitions known as "automatic thoughts" (ATs) which are dysfunctional or negative views of the self, world, or future based upon already existing beliefs about oneself, the world, or the future[14]

- Identification of the cognitive distortions in the ATs

- Rational disputation of ATs with the Socratic method

- Development of a rational rebuttal to the ATs

There are six types of automatic thoughts:[13]

- Self-evaluated thoughts

- Thoughts about the evaluations of others

- Evaluative thoughts about the other person with whom they are interacting

- Thoughts about coping strategies and behavioral plans

- Thoughts of avoidance

- Any other thoughts that were not categorized

Other major techniques include:

- Activity monitoring and activity scheduling

- Behavioral experiments

- Catching, checking, and changing thoughts

- Collaborative empiricism: the therapist and client work together as equal partners in addressing issues and fostering change through mutual understanding, communication, and respect. The therapist and patient become investigators by examining the evidence to support or reject the patient's cognitions. Empirical evidence is used to determine whether particular cognitions serve any useful purpose.[15]

- Downward arrow technique

- Exposure and response prevention

- Cost benefit analysis

- acting "as if"[16]

- Guided discovery: therapist elucidates behavioral problems and faulty thinking by designing new experiences that lead to acquisition of new skills and perspectives. Through both cognitive and behavioral methods, the patient discovers more adaptive ways of thinking and coping with environmental stressors by correcting cognitive processing.[15]

- Mastery and pleasure technique

- Problem solving

- Socratic questioning: involves the creation of a series of questions to a) clarify and define problems, b) assist in the identification of thoughts, images and assumptions, c) examine the meanings of events for the patient, and d) assess the consequences of maintaining maladaptive thoughts and behaviors.[15]

Socratic questioning

Socratic questions are the archetypal cognitive restructuring techniques. These kinds of questions are designed to challenge assumptions by:[10]

- Conceiving reasonable alternatives:

"What might be another explanation or viewpoint of the situation? Why else did it happen?"

- Evaluating those consequences:

"What's the effect of thinking or believing this? What could be the effect of thinking differently and no longer holding onto this belief?"

- Distancing:

"Imagine a specific friend/family member in the same situation or if they viewed the situation this way, what would I tell them?"

Examples of socratic questions are:

- "Describe the way you formed your viewpoint originally."

- "What initially convinced you that your current view is the best one available?"

- "Think of three pieces of evidence that contradict this view, or that support the opposite view. Think about the opposite of this viewpoint and reflect on it for a moment. What's the strongest argument in favor of this opposite view?"

- "Write down any specific benefits you get from holding this belief, such as social or psychological benefits. For example, getting to be part of a community of like-minded people, feeling good about yourself or the world, feeling that your viewpoint is superior to others", etc. Are there any reasons that you might hold this view other than because it's true?"

- "For instance, does holding this viewpoint provide some peace of mind that holding a different viewpoint would not?"

- "In order to refine your viewpoint so that it's as accurate as possible, it's important to challenge it directly on occasion and consider whether there are reasons that it might not be true. What do you think the best or strongest argument against this perspective is?"

- "What would you have to experience or find out in order for you to change your mind about this viewpoint?"

- "Given your thoughts so far, do you think that there may be a truer, more accurate, or more nuanced version of your original view that you could state right now?"

False assumptions

False assumptions are based on "cognitive distortions," such as:[17]

- Always Being Right: In this cognitive distortion, you see your own opinions as facts of life. This is why you will go to great lengths to prove you’re right. For example, 'You quarrel with your sibling about how your parents haven’t supported you enough. You’re convinced this was the case all the time, while your sibling believes it varied according to the situation. Since your sibling doesn’t feel the same way, you become angry and say things that rub your sibling the wrong way. You know they’re getting upset, but you continue the argument to prove your point."

- Control fallacies: These can go in two opposite directions: You either feel responsible or in control of everything in your and other people’s lives, or you feel you have no control at all over anything in your life. An example of the first type: "You think you make someone else happy or unhappy. You think all of their emotions are controlled directly or indirectly by your behaviors." An example of the second type: "You couldn’t complete a report that was due today. You immediately think, 'Of course I couldn’t complete it! My boss is overworking me, and everyone was so loud today at the office. Who can get anything done like that?'"

- Overgeneralization: With overgeneralization, words like ‚Äúalways,‚ÄĚ ‚Äúnever,‚ÄĚ ‚Äúeverything,‚ÄĚ and ‚Äúnothing‚ÄĚ are frequent in your train of thought. For example, "You speak up at a team meeting, and your suggestions are not included in the project. You leave the meeting thinking, 'I ruined my chances for a promotion. I never say the right thing!'"

- Jumping to conclusions: When you jump to conclusions, you interpret an event or situation negatively without evidence supporting such a conclusion. Then, you react to your assumption. For example, "Your partner comes home looking serious. Instead of asking how they are, you immediately assume they’re mad at you. Consequently, you keep your distance. In reality, your partner had a bad day at work."

Applications

Depression

According to Beck's theory of the etiology of depression, depressed people acquire a negative schema of the world in childhood and adolescence; children and adolescents who experience depression acquire this negative schema earlier. Depressed people acquire such schemas through the loss of a parent, rejection by peers, bullying, criticism from teachers or parents, the depressive attitude of a parent, or other negative events. When a person with such schemas encounters a situation that resembles the original conditions of the learned schema, the negative schemas are activated.[18]

Beck's negative triad holds that depressed people have negative thoughts about themselves, their experiences in the world, and the future.[19] For instance, a depressed person might think, "I didn't get the job because I'm terrible at interviews. Interviewers never like me, and no one will ever want to hire me." In the same situation, a person who is not depressed might think, "The interviewer wasn't paying much attention to me. Maybe she already had someone else in mind for the job. Next time I'll have better luck, and I'll get a job soon." Beck also identified a number of other cognitive distortions, which can contribute to depression, including the following: arbitrary inference, selective abstraction, overgeneralization, magnification and minimization.[18]

In 2008, Beck proposed an integrative developmental model of depression[20] that aimed to incorporate research in genetics and the neuroscience of depression. This model was updated in 2016 to incorporate multiple levels of analyses, new research, and key concepts (e.g., resilience) within the framework of an evolutionary perspective.[21]

Other applications

Cognitive therapy has been applied to a very wide range of behavioral health issues,[22] including:

- Anxiety disorders[23]

- Bipolar disorder[24]

- Borderline personality disorder[22]

- Low self-esteem[25]

- Narcissistic personality disorder[22]

- Paranoid personality disorder[22]

- Phobia[26]

- Schizophrenia[27]

- Substance abuse[28]

- Suicidal ideation[29]

- Weight loss[30]

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ Daniel Robertson, The Philosophy of Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy: Stoicism as Rational and Cognitive Psychotherapy (Routledge, 2019, ISBN 978-0367219147).

- ‚ÜĎ Aaron T. Beck, A. John Rush, Brian F. Shaw, and Gary Emery, Cognitive Therapy of Depression (The Guilford Press, 1987, ISBN 978-0898629194).

- ‚ÜĎ 3.0 3.1 Danny Wedding and Raymond J. Corsini, Current Psychotherapies (Cengage Learning, 2018, ISBN 978-1305865754).

- ‚ÜĎ Michael G. Brock, The truth is indeed sobering Detroit Legal News (March 18, 2015). Retrieved March 19, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ Erica Goode, A Pragmatic Man and His No-Nonsense Therapy The New York Times (January 11, 2000). Retrieved March 19, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ Aaron T. Beck, Depression: Causes and treatment (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1972 (original 1967), ISBN 978-0812276527).

- ‚ÜĎ Aaron T. Beck, Cognitive Therapy and the Emotional Disorders (Madison, CT: International Universities Press, Inc., 1975, ISBN 978-0823609901).

- ‚ÜĎ Aaron T. Beck, Does Cognitive Therapy = Cognitive Behavior Therapy? The Beck Institute, February 21, 2007. Retrieved March 19, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ History of Beck Institute The Beck Institute. Retrieved March 19, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ 10.0 10.1 Judith S. Beck, Cognitive Therapy: Basics and Beyond (The Guilford Press, 1995, ISBN 978-0898628470).

- ‚ÜĎ 11.0 11.1 Judith S. Beck, Cognitive Behavior Therapy: Basics and Beyond (The Guilford Press, 2020, ISBN 978-1462544196).

- ‚ÜĎ Academy of Cognitive and Behavioral Therapies (A-CBT). Retrieved March 29, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ 13.0 13.1 Debra A. Hope, James A. Burns, Sarah A. Hayes, James D. Herbert, and Michelle D. Warner, Automatic Thoughts and Cognitive Restructuring in Cognitive Behavioral Group Therapy for Social Anxiety Disorder Cognitive Therapy and Research 34(1) (February 2010): 1‚Äď12. Retrieved March 19, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ Samuel T. Gladding, Counseling: A Comprehensive Profession (Pearson College Div., 2006, ISBN 978-0132328623).

- ‚ÜĎ 15.0 15.1 15.2 James C. Overholser, Collaborative Empiricism, Guided Discovery, and the Socratic Method: Core Processes for Effective Cognitive Therapy Clinical Psychology 18(1) (March 2011):62-66. Retrieved March 19, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ The "Act As If" Technique Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Los Angeles, October 14, 2023. Retrieved March 19, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ Sandra Silva Casabianca, 15 Common Cognitive Distortions Psych Central, January 11, 2022. Retrieved March 19, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ 18.0 18.1 Ann M. Kring and Sheri L. Johnson, Abnormal Psychology (Wiley, 2022, ISBN 978-1119859918).

- ‚ÜĎ Aaron T. Beck, A. John Rush, Brian F. Shaw, and Gary Emery, Cognitive Therapy of Depression (The Guilford Press, 1987, ISBN 978-0898629194).

- ‚ÜĎ Aaron T. Beck, The Evolution of the Cognitive Model of Depression and Its Neurobiological Correlates Am J Psychiatry 165(8) (2008):969‚Äď977. Retrieved March 19, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ Aaron T. Beck and Keith Bredemeier, A Unified Model of Depression: Integrating Clinical, Cognitive, Biological, and Evolutionary Perspectives Clinical Psychological Science 4(4) (2016):596‚Äď619. Retrieved March 19, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 James Pretzer, Barbara Fleming, and Karen M. Simon, Clinical Applications of Cognitive Therapy (Springer, 2004, ISBN 978-0306484629).

- ‚ÜĎ David A. Clark and Aaron T. Beck, Cognitive Therapy of Anxiety Disorders: Science and Practice (The Guilford Press, 2011, ISBN 978-1609189921).

- ‚ÜĎ Cory F. Newman, Robert L. Leahy, Aaron T. Beck, Noreen Reilly-Harrington, and Laszlo Gyulai, Bipolar Disorder: A Cognitive Therapy Approach (American Psychological Association, 2002, ISBN 1557987890).

- ‚ÜĎ Matthew McKay and Patrick Fanning, Self-Esteem: A Proven Program of Cognitive Techniques for Assessing, Improving, and Maintaining Your Self-Esteem (New Harbinger Publications, 2016, ISBN 978-1626253933).

- ‚ÜĎ Aaron T. Beck and Gary Emery, Anxiety Disorders and Phobias: A Cognitive Perspective (New York: Basic Books, 2005, ISBN 978-0465005871).

- ‚ÜĎ Aaron T. Beck, Neil A. Rector, Neal Stolar, and Paul Grant, Schizophrenia: Cognitive Theory, Research, and Therapy (The Guilford Press, 2011, ISBN 978-1609182380).

- ‚ÜĎ Aaron T. Beck, Fred D. Wright, Cory F. Newman, and Bruce S. Liese, Cognitive Therapy of Substance Abuse (The Guilford Press, 1993, ISBN 978-0898621150).

- ‚ÜĎ Amy Wenzel, Gregory K. Brown, and Aaron T. Beck, Cognitive Therapy for Suicidal Patients: Scientific and Clinical Applications (American Psychological Association, 2008, ISBN 978-1433804076).

- ‚ÜĎ Judith Beck, The Beck Diet Solution: Train Your Brain to Think Like a Thin Person (Oxmoor House, 2007, ISBN 978-0848731731).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Beck, Aaron T. Depression: Causes and treatment. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1972 (original 1967). ISBN 978-0812276527

- Beck, Aaron T. Cognitive Therapy and the Emotional Disorders. Madison, CT: International Universities Press, Inc., 1975. ISBN 978-0823609901

- Beck, Aaron T., Fred D. Wright, Cory F. Newman, and Bruce S. Liese. Cognitive Therapy of Substance Abuse. The Guilford Press, 1993. ISBN 978-0898621150

- Beck, Aaron T., and Gary Emery. Anxiety Disorders and Phobias: A Cognitive Perspective. New York: Basic Books, 2005. ISBN 978-0465005871

- Beck, Aaron T., Neil A. Rector, Neal Stolar, and Paul Grant,. Schizophrenia: Cognitive Theory, Research, and Therapy. The Guilford Press, 2011. ISBN 978-1609182380

- Beck, Aaron T., A. John Rush, Brian F. Shaw, and Gary Emery. Cognitive Therapy of Depression. The Guilford Press, 1987. ISBN 978-0898629194

- Beck, Judith S. Cognitive Therapy: Basics and Beyond. The Guilford Press, 1995. ISBN 978-0898628470

- Beck, Judith S. The Beck Diet Solution: Train Your Brain to Think Like a Thin Person. Oxmoor House, 2007. ISBN 978-0848731731

- Beck, Judith S. Cognitive Behavior Therapy: Basics and Beyond. The Guilford Press, 2020. ISBN 978-1462544196

- Clark, David A., and Aaron T. Beck. Cognitive Therapy of Anxiety Disorders: Science and Practice. The Guilford Press, 2011, ISBN 978-1609189921

- Gladding, Samuel T. Counseling: A Comprehensive Profession. Pearson College Div., 2006. ISBN 978-0132328623

- Kring, Ann M., and Sheri L. Johnson. Abnormal Psychology. Wiley, 2022. ISBN 978-1119859918

- McKay, Matthew, and Patrick Fanning. Self-Esteem: A Proven Program of Cognitive Techniques for Assessing, Improving, and Maintaining Your Self-Esteem. New Harbinger Publications, 2016. ISBN 978-1626253933

- Newman, Cory F., Robert L. Leahy, Aaron T. Beck, Noreen Reilly-Harrington, and Laszlo Gyulai. Bipolar Disorder: A Cognitive Therapy Approach. American Psychological Association, 2002. ISBN 1557987890

- Pretzer, James, Barbara Fleming, and Karen M. Simon. Clinical Applications of Cognitive Therapy. Springer, 2004. ISBN 978-0306484629

- Robertson, Daniel. The Philosophy of Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy: Stoicism as Rational and Cognitive Psychotherapy. Routledge, 2019. ISBN 978-0367219147

- Wedding, Danny, and Raymond J. Corsini. Current Psychotherapies. Cengage Learning, 2018. ISBN 978-1305865754

- Wenzel, Amy, Gregory K. Brown, and Aaron T. Beck. Cognitive Therapy for Suicidal Patients: Scientific and Clinical Applications. American Psychological Association, 2008. ISBN 978-1433804076

External links

All links retrieved March 19, 2024.

- An Introduction to Cognitive Therapy & Cognitive Behavioural Approaches Counselling Resource

- Cognitive Therapy (CT) American Psychological Association

- Cognitive therapy (CT): definition, application, and effectivity The Diamond Rehab Thailand

- Does Cognitive Therapy = Cognitive Behavior Therapy? The Beck Institute for Cognitive Behavior Therapy

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.