Chennakesava Temple

The Chennakesava Temple (Kannada: ಶ್ರೀ ಚೆನ್ನಕೇಶವ ದೇವಸ್ಥಾನ), originally called Vijayanarayana Temple (Kannada: ವಿಜಯನಾರಾಯಣ ದೇವಸ್ಥಾನ), built on the banks of the Yagachi River in Belur, served as an early capital of the Hoysala Empire. Belur sits 40 km from Hassan city and 220 km from Bangalore, in Hassan district of Karnataka state, India. Chennakesava means "handsome Kesava." The Hoysalas earned renown for their temple architecture, the Chennakesava Temple in the capital city of Belur representing of the foremost examples. UNESCO has proposed the temple site, along with the Hoysaleswara temple in Halebidu, for designation as a World Heritage site.

The Hoysala Empire of southern India prevailed during the tenth to fourteenth centuries C.E., with its capital in Belur at first. The empire covered most of modern Karnataka, parts of Tamil Nadu and parts of western Andhra Pradesh in Deccan India. Hoysala architecture, like displayed in Chennakesava Temple, developed from the Western Chalukya style with Dravidian influences. The style of architecture is known as Karnata Dravida, a unique expression of Hindu temple architecture distinguished by exacting attention to detail and exceptionally skilled craftsmanship. Other outstanding examples of Hoysala temple architecture include the Chennakesava Temple at Somanathapura (1279 C.E.), the temples at Arasikere (1220 C.E.), Amrithapura (1196 C.E.), Belavadi (1200 C.E.) and Nuggehalli (1246 C.E.)

The total effect of the Chennakesava Temple is to leave the visitor awe struck and the devotee inspired. As the central temple for the capital city of Belur in the early history, Chennakesava served to display the grandeur of the Hoysala empire. The enormous wealth, and vast pool of talented craftsmen, required to construct the matchless temple gave a message of the empire's tremendous power.

History

Hoysala king Vishnuvardhana commissioned the temple in 1117 C.E. The reasons for the construction of the temple have been debated. The popular belief holds the military success of Vishnuvardhana as the reason.[1] Another view holds that Vishnuvardhana commissioned the temple to surpass the Hoysala overlords, the Western Chalukyas who ruled from Basavakalyan, after his victories against the Chalukyas.[2]Another view holds that Vishnuvardhana celebrated his famous victory against the Cholas of Tamil country in the battle of Talakad leading to the Hoysalas taking control of Gangavadi (southern regions of Karnataka).[3] Yet another explanation pertains to Vishnuvardhana's conversion from Jainism to Vaishnavism, considering that Chennakesava had been predominantly a Vaishnava temple.[4] The Hoysalas had many brilliant architects who developed a new architectural idiom. A total of 118 inscriptions have been recovered from the temple complex covering a period of 1117 to eighteenth century which give details of the artists employed, grants made to the temple and renovations.

Temple complex

A Rayagopura, built during the days of Vijayanagar empire, crowns the main entrance to the complex.[5] The Chennakesava temple stands in the center of the temple complex, facing east and flanked by Kappe Channigraya temple and a small Lakshmi temple on its right. On its left, and to its back, stands an Andal temple. Of the two main Sthambha (pillars) that exist, the one facing the main temple had been built in the Vijayanagar period. The one to the right comes from the Hoysala time. While that represents the first great Hoysala temple, the artistic idiom remains Western Chalukyan. Hence the lack of over decoration, unlike later Hoysala temples, including the Hoysaleswara temple at Halebidu and the Keshava temple at Somanathapura.

Later, Hoysala art inclined towards craftsmanship, with a preference for minutia.[6] The temple has three entrances, the doorways have highly decorated sculptures of doorkeepers (dvarapalaka). While the Kappe Channigraya temple measures smaller than the Chennakesava temple, its architecture stands equal although lacking sculptural features. That became a dvikuta (two shrined) with the addition of a shrine to its original plan. The original shrine has a star shaped plan while the additional shrine forms a simple square. The icon inside, commissioned by Shantala Devi, queen of king Vishnuvardhana follows the Kesava tradition.

Temple plan

Craftsmen built the Chennakesava temple with Chloritic Schist (soapstone)[7] essentially a simple Hoysala plan built with extraordinary detail. The unusually large size of the basic parts of the temple differentiates that temple from other Hoysala temples of the same plan.[8]

The temple follows a ekakuta vimana design (single shrine) of 10.5 m by 10.5 m size. A large vestibule connects the shrine to the mandapa (hall), one of the main attractions of the temple. The mandapa has 60 bays.[9] The superstructure (tower) on top of the vimana has been lost over time. The temple sits on a jagati (platform).[10]

One flight of steps leads to the jagati and another flight of steps to the mantapa. The jagati provides the devotee an opportunity for a pradakshina (circumambulation) around the temple before entering it. The jagati carefully follows the staggered square design of the mantapa[11] and the star shape of the shrine. The mantapa originally had an open design. A visitor could see the ornate pillars of the open mantapa from the platform. The mantapa, perhaps the most magnificent one in all of medieval India,[12] the open mantapa converted into a closed one 50 years into the Hoysala rule by erecting walls with pierced window screens. The 28 window screens sit on top of 2 m high walls with star shaped piercing and bands of foliage, figures and mythological subjects. On one such screen, king Vishnuvardhana and his queen Shanatala Devi have been depicted. An icon depicts the king in a standing posture.[13]

Shrine

The vimana (shrine) stands at the back of the mantapa. Each side of the vimana measures 10.5 m and has five vertical sections: a large double storied niche in the center and two heavy pillar like sections on both sides of that niche. The two pillar like sections adjoining the niche have been rotated about their vertical axis to produce a star shaped plan for the shrine.[14] The pillar like section and the niche bear many ornate sculptures, belonging to an early style. Sixty large sculptures of deities, from both Vaishnava and Shaiva faiths, stand in place. The shape of the vimana infers that the tower above would have been of the Bhumija style and not the regular star shaped tower that follows the shape of the vimana. The Bhumija towers on the miniature shrines at the entrance of the hall actually classify as a type of nagara design (being curvilinear in shape),[15] an uncommon shape of tower in pure dravidian design. The shrine has a life size (about 6 ft) image of Kesava (a form of Vishnu) with four hands holding the discus (chakra), mace (gadha), lotus-flower (padma) and conch (Shanka) in clockwise direction. Life size sculptures of door guardians (dvarapalaka) flank the entrance to the shrine.

Pillars and Sculptures

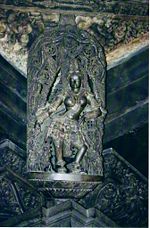

The pillars inside the hall stand out as a major attraction, the Narasimha pillar, at one time thought to have revolved (on its ball bearings), the most popular.[16] A rich diversity exists in their style. While all the 48 pillars and the many ceilings have decorations, nothing surpasses the finish of the four central pillars and the central ceiling. Those pillars may have been hand churned while the others had been lathe turned.[17] All four pillars bear madanikas (celestial nymphs) 42 total, 4 inside the hall and the rest outside between the eaves on the outer walls of the hall.[18] Also called madanakai, salabanjika or shilabalika, they epitomize the ideal female form, depicted as dancers, musicians, drummers, and rarely erotic in nature. The Darpana Sundari (beauty with mirror), "The lady with the parrot," "The huntress" and Bhasma mohini number among the most popular madanika with tourists.[19]

Other interesting sculptures inside the mantapa include Sthamba buttalika (pillar images), more in the Chola idiom indicating that the Hoysalas may have employed Chola craftsman along with locals. Those images have less decor than regular Hoysala sculptures, the mohini pillar providing an example.[20]

Friezes (rectangular band of sculptures) of charging elephants (650 of them) decorate the base of the outer walls,[21]symbolizing stability and strength. In a style called horizontal treatment with friezes, above them lions, symbolizing courage and further up horses, symbolizing speed embellish the walls. Panels with floral designs signify beauty. Above them, panels depicting Ramayana and Mahabharatahave been set.[22] Hoysala artistry preferred discretion about sexuality, mingling miniature erotic sculptures in unconspicuous places like recesses and niches. Sculptures depict daily life in a broad sense.

The doorways to the mantapa have on both sides the sculpture of Sala slaying a Tiger. Popularly known as the founder of the empire, Sala's appears on sukanasi (nose of the main tower formed by a lower tower on top of the vestibule) next to the main tower. Legend relates that Sala killed a tiger ready to pounce on the meditating muni (saint) who sought Sala's help in killing the tiger. Some historians speculate that the legend may have gained importance after the victory of Vishnuvardhana over the Cholas at Talakad, the tiger serving as the royal emblem of the Cholas.[23]

The Narasimha image in the south western corner, Shiva-Gajasura (Shiva slaying demon in form of elephant) on the western side, the winged Garuda, consort of Lord Vishnu standing facing the temple, dancing Kali, a seated Ganesha, a pair consisting of a boy with an umbrella and a king (Vamana avatar or incarnation of Vishnu), Ravana shaking Mount Kailash, Durga slaying demon Mahishasura, standing Brahma, Varaha (avatar of Vishnu), Shiva dancing on demon (Andhakasura), Bhairava (avatar of Shiva) and Surya number among other important images. The sculptural style of the wall images shows close similarity to wall images in contemporary temples in northern Karnataka and adjacent Maharashtra and hence a Western Chalukya idiom.

Artists

The Hoysala artists, unlike many medieval artists, preferred to sign their work in the form of inscriptions. They sometimes revealed fascinating details about themselves, their families, guilds and place of origin.[24] Stone and copper plate inscriptions provide more information about them. Ruvari Mallitamma, a prolific artist, had more than 40 sculptures attributed to him in Chennakesava. Dasoja and his son Chavana, from Balligavi in Shimoga district, also made many contributions. Chavana has been credited with the work on five madanika and Dasoja with four. Malliyanna and Nagoja created birds and animals in their sculptures. Artists Chikkahampa and Malloja have been credited with some the sculptures in the mantapa.[25]

See Also

- Hoysala architecture

- Hoysaleswara temple

- Chennakesava Temple at Somanathapura

Notes

- ↑ Gerard Foekema. A Complete Guide to Hoysala Temples. (New Delhi: Abhinav Publications, 1996), 47

- ↑ S. Settar, Hoysala HeritageFrontline, 20 (08) (April 12 - 25, 2003) accessdate=2008-06-15

- ↑ S.U. Kamath. A Concise History of Karnataka: from pre-historic times to the present. (Bangalore: Archana Prakashana, 1980), 124

- ↑ According Settar, records do not support that theory, Hoysala Heritage Frontline 20 (08) (April 12 - 25, 2003) accessdate 2008-06-23

- ↑ Kamath, 183

- ↑ Settar Hoysala Heritage. Frontline 20 (08) (April 12 - 25, 2003) accessdate 2008-06-23

- ↑ Kamath, 136. The Western Chalukya carvings on green schist (soapstone) technique had been adopted by the Hoysalas too, Takeo Kamiya, September 20, 1996, Architecture of the Indian subcontinent Gerard da Cunha-Architecture Autonomous, (Bardez, Goa, India) accessdate 2008-06-15

- ↑ Its architectural plan follows an innovation of nagara (north Indian) design popular in the imperial city of Basavakalyan in northern Karnataka at that time. Gerard Foekema, Jayashree Kannikeswaran, The Templenet Encyclopedia - Temples of Karnataka-Chennakesava Temple at Belur TempleNet. accessdate 2008-06-23.

- ↑ "A bay forms a square or rectangular compartment in the hall," Foekema, 93

- ↑ The jagati serves as a pradakshina patha or path for circumambulation, as the shrine has no such arrangements, Kamath, 135. That platform follows a uniquely Hoysalas architectural design. Mangalore Arthikaje, Religion, Literature, Art and Architecture in Hoysala Empire. © 1998-2000 OurKarnataka.Com, Inc. accessdate 2008-06-15

- ↑ The Hoysala plan for open mantapa almost always follows a staggered square design. That results in many projections and recesses, Foekema, 22

- ↑ Foekema, 48

- ↑ The pierced windows commonly appear in earlier Western Chalukya temples also, Kamath, 116

- ↑ Foekema, 49

- ↑ Foekema, 50

- ↑ Shruti Nanavaty, Belur - A Temple Retreat. TempleNet. accessdate 2008-06-15

- ↑ Kamath, 117

- ↑ Foekema, 93

- ↑ Nanavaty, Belur - A Temple Retreat.TempleNet. accessdate 2008-06-15

- ↑ Settar, Hoysala Heritage. Frontline 20 (08) (April 12 - 25, 2003). accessdate 2008-06-23}

- ↑ Foekema, 93

- ↑ Kamath, 134

- ↑ Kamath, 123; The Hoysalas and their contributions. © 1998-2000 OurKarnataka.Com, Inc. accessdate 2008-06-15

- ↑ Settar, Hoysala Heritage. Frontline 20 (08) (April 12 - 25, 2003) accessdate 2008-06-15

- ↑ Jyotsna Kamath, Kamat's Potpourri November 04, 2006, Hoysala Temples of Belur. © 1996-2006 accessdate 2008-06-15

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Foekema, Gerard. 1996. A complete guide to Hoysaḷa temples. New Delhi: Abhinav Publications. ISBN 9788170173458.

- Hardy, Adam. 1995. Indian temple architecture: form and transformation: the Karṇāṭa Drāviḍa tradition, 7th to 13th centuries. New Delhi: Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts. ISBN 9788170173120.

- Kāmat, Sūryanātha. 1980. A concise history of Karnataka: from pre-historic times to the present. Bangalore: Archana Prakashana. OCLC 7796041.

- Nilakanta Sastri, K. A. 1990. A history of South India from prehistoric times to the fall of Vijayanagar. Oxford India paperbacks. Bombay: Oxford University Press. OCLC 35690171.

External links

All links retrieved December 5, 2023.

- Hoysala art and architecture Jyotsna Kamat

- Hoysala heritage

- TempleNet, Chennakesava Temple at Belur

- TempleNet, Belur - A Temple Retreat

- Photo of Gopura - Chennakeshava Temple

- Plan of temple

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.