Difference between revisions of "Yuman" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

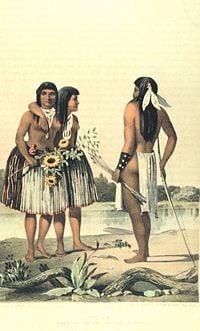

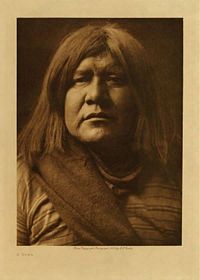

[[Image:Edward S. Curtis Collection People 038.jpg|thumb|200 px|left|Hwalya - Yuma by Edward S. Curtis, 1908]] | [[Image:Edward S. Curtis Collection People 038.jpg|thumb|200 px|left|Hwalya - Yuma by Edward S. Curtis, 1908]] | ||

===History=== | ===History=== | ||

| − | The sixteenth century Spanish expedition under [[Hernando de Alarcón]], intended to meet [[Francisco Vasquéz de Coronado]]'s overland expedition, visited the peninsula of [[Baja California]] and then traveled along the lower Colorado River. This was the first European expedition to reach Yuman territory. Until the eighteenth century, however, contact with the Yuman was intermittent. For example, the Kiliwa first encountered Europeans when [[Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo]] reached the San Quintín area in 1542. [[Sebastián Vizcaíno]]'s expedition mapped the northwest coast of Baja California in 1602 and encountered the Paipai. More intensive and sustained contacts began in 1769 when the expedition to establish Spanish settlements in California, led by [[Gaspar de Portolà]] and [[Junípero Serra]], passed through the western portions. [[Juan Bautista de Anza]] and his party traveled into Quechan territory in the winter of 1774, marking the beginning of continuous interaction. | + | The sixteenth century Spanish expedition under [[Hernando de Alarcón]], intended to meet [[Francisco Vasquéz de Coronado]]'s overland expedition, visited the peninsula of [[Baja California]] and then traveled along the lower Colorado River. This was the first European expedition to reach Yuman territory. Until the eighteenth century, however, contact with the Yuman was intermittent. For example, the Kiliwa first encountered Europeans when [[Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo]] reached the San Quintín area in 1542. [[Sebastián Vizcaíno]]'s expedition mapped the northwest coast of Baja California in 1602 and encountered the Paipai. The [[Society of Jesus|Jesuit]] missionary-explorer [[Wenceslaus Linck]] came overland from the south into the eastern part of Kiliwa territory in 1766. More intensive and sustained contacts began in 1769 when the expedition to establish Spanish settlements in California, led by [[Gaspar de Portolà]] and [[Junípero Serra]], passed through the western portions. [[Juan Bautista de Anza]] and his party traveled into Quechan territory in the winter of 1774, marking the beginning of continuous interaction. |

===Culture=== | ===Culture=== | ||

Revision as of 19:07, 17 September 2008

The Yuman are Native American tribes who live along the lower Colorado River in Arizona and California as well as in Baja California.

The languages of the Yuman tribes are classified into the Yuman language family, which may form part of the hypothetical Hokan linguistic phylum.

Yuman tribes

The term Patayan is used by archaeologists to describe the prehistoric Native American cultures that inhabited parts of modern day Arizona, California and Baja California, including areas near the Colorado River Valley, the nearby uplands, and north to the vicinity of the Grand Canyon. These prehistoric people appear to be ancestoral to the Yuman. They practiced floodplain agriculture where possible, but relied heavily on hunting and gathering. The historic Yuman-speaking peoples in this region were skilled warriors and active traders, maintaining exchange networks with the Pima in southern Arizona and with the Pacific coast.

The Yuman can be divided into two distinct groups: The River Yumans inhabited the areas along the Colorado River near the junction with the Gila River; the Upland Yumans lived near the Grand Canyon and areas of Southern California, particularly Baja California. The Mohave, Cocopha, Maricopa, and Quechan are included in the River Yumans, while the Hualapia, Havasupai, Yavapai, Diegueño, Kiliwa, and Paipai are the main tribes of the Upland Yumans.

History

The sixteenth century Spanish expedition under Hernando de Alarcón, intended to meet Francisco Vasquéz de Coronado's overland expedition, visited the peninsula of Baja California and then traveled along the lower Colorado River. This was the first European expedition to reach Yuman territory. Until the eighteenth century, however, contact with the Yuman was intermittent. For example, the Kiliwa first encountered Europeans when Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo reached the San Quintín area in 1542. Sebastián Vizcaíno's expedition mapped the northwest coast of Baja California in 1602 and encountered the Paipai. The Jesuit missionary-explorer Wenceslaus Linck came overland from the south into the eastern part of Kiliwa territory in 1766. More intensive and sustained contacts began in 1769 when the expedition to establish Spanish settlements in California, led by Gaspar de Portolà and Junípero Serra, passed through the western portions. Juan Bautista de Anza and his party traveled into Quechan territory in the winter of 1774, marking the beginning of continuous interaction.

Culture

Yuman people generally had a loose political organization, and lived in small, impermanent settlements. Several of the tribes were warlike in spirit, and valued success in battle over material possessions. Unlike other Native Americans, they had private, or family, ownership of land, but no inheritance. Upon the death of the owner, land was usually abandoned.

Their traditional religious beliefs are characterized by belief in a supreme creator. Their traditions were passed on through traditional narratives and songs.

River Yuman

The River Yuman, who inhabited the area around the lower Colorado and [{Gila River]]s, farmed the floodplain. Annual flooding of the rivers deposited silt and naturally irrigated the land, making for fertile soil. Their lifestyle thus involved permanent settlements above the floodplain and temporary shelters which they used during the farming season after the floods had receded.

- Cocopah

The Cocopah live in Baja California, Mexico, and some emigated and settled on the lower reaches of the Colorado River. As of the 2000 census a resident population of 1,025 persons, of whom 519 were solely of Native American heritage, lived on the 25.948 km² (10.0185 sq mi) Cocopah Indian Reservation, which is composed of several non-contiguous sections in Yuma County, Arizona, lying southwest and northwest of the city of Yuma, Arizona. There is a casino and bingo hall on the reservation.

- Maricopa

The Maricopa, or Piipaash, live in the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community and Gila River Indian Community along with the Pima, a tribe with whom the Maricopa have long held a positive relationship. They formerly consisted of small groups of people situated on the banks of the Colorado River. Robert "Tree" Cody, a notable performer of the Native American flute is of Maricopa and Sioux heritage.

- Mohave

Mohave and Mojave are both tribally accepted and interchangeably used phonetic spellings for these people known among themselves as the Aha macave. Their name comes from two words: aha, meaning 'water', and macave, meaning "along or beside," and to them it means "people who live along the river."

Today, many of the surviving descendants of these indigenous old families live on or near one of two reservations located on the Colorado River. The Fort Mojave Indian Reservation includes parts of California, Arizona, and Nevada. The Colorado River Indian Reservation includes parts of California and Arizona and is shared by members of the Chemehuevi, Hopi, and Navajo nations.

The original Colorado River and Fort Mojave land reservations were established in 1865 and 1870, respectively. Both reservations include substantial senior water rights in the Colorado River, which are used for irrigated farming. Though the four combined groups of families sharing the Colorado River Indian Reservation function today as one geo-political unit, the Colorado River Indian Tribes, each continues to maintain and observe its individual traditions, distinct religions, and culturally unique identities.

The tribal headquarters, library and museum are in Parker, Arizona, about 40 miles (64 km) north of I-10. The National Indian Days Celebration is held annually in Parker, from Thursday through Sunday during the last week of September. The All Indian Rodeo is also celebrated annually, on the first weekend in December.

- Quechan

The Quechan (also Yuma, Kwtsan, Kwtsaan) live on the Fort Yuma Reservation on the lower Colorado River in Arizona just north of the border with Mexico. The reservation is a part of their traditional lands. Established in 1884, the Fort Yuma Indian Reservation has a land area of 178.197 km² (68.802 sq mi) in southeastern Imperial County, California, and western Yuma County, Arizona, near the city of Yuma, Arizona. The Quechan are one of the Yuman tribes. They should not be confused with the Quechuas, which is the term used for several ethnic groups that use a Quechua language in South America, particularly in Peru, Ecuador, Bolivia, Chile, and Argentina.

Kroeber estimated the population of the Quechan in 1910 as 750. By 1950, there were reported to be just under 1,000 Quechan living on the reservation and another 1,100+ off it (Forbes 1965, 343). The 2000 census reported a resident population of 2,376 persons on the Fort Yuma Indian Reservation, only 56.8 percent of whom were of solely Native American heritage, and more than 27 percent of whom were white.

The Quechan lived in small settlements, above the floodplain where the Colorado and Gila Rivers flooded every spring. There they established rectangular, open-sided dwellings. In the period after the floods until fall the people farmed small plots of land owned by each family, living in small dome-shaped wickiup shelters.

Quechan traditional narratives include myths, legends, tales, and oral histories preserved by the Quechan people. The Southern California Creation myth is particularly prominent in Quechan oral literature. This and other narrative elements are shared with the other Yuman-speaking peoples of southern California, western Arizona, and northern Baja California, as well as with their Uto-Aztecan-speaking neighbors.

The best crossing point of the Colorado River, just south of its junction with the Gila River, was under Quechan control. The Quechan, warlike in attitude, were constantly fighting other tribes in the area to maintain their superiority.

The first important contact of the Quechan with Europeans was with the Spanish explorer Juan Bautista de Anza and his party in the winter of 1774. Relations were friendly and on Anza's return from his second trip to Alta California in 1776 the chief of the tribe and three others journeyed to Mexico City to petition the Viceroy of New Spain for the establishment of a mission. The chief Palma and his three companions were baptized there on February 13, 1777. Palma was given the name Salvador Carlos Antonio.

Spanish settlement among the Quechan did not go as well as hoped and the tribe rebelled on July 17, 1781 and killed four priests and 30 soldiers. The Spanish mission settlements of San Pedro y San Pablo de Bicuñer and Puerto de Purísima Concepción were also decimated. The Quechan retained control over the area until the Yuma Expedition, which established Fort Yuma at the crossing of the Colorado River. This was a military operation to control the unrest of the Yuma in California from December, 1851, to April, 1852, part of the long history of Indian Wars between the United States and Native Americans that took place before the American Civil War.

In 1884, a reservation was established on the California side of the river for the Quechan. The Fort Yuma Indian Reservation has a land area of 178.197 km² (68.802 sq mi) in southeastern Imperial County, California, and western Yuma County, Arizona, near the city of Yuma, Arizona. The reservation consists of part of their traditional lands.

Upland Yuman

- Diegueño

The Kumeyaay, also known as the Diegueño, live in the extreme southwestern United States and northwest Mexico, in the states of California and Baja California. In Spanish, the name is commonly spelled kumiai.

The Kumeyaay live on 13 reservations in San Diego County, California (Barona, Campo, Capitan Grande, Ewiiapaayp, Inaja, Jamul, La Posta, Manzanita, Mesa Grande, San Pasqual, Santa Ysabel, Sycuan, and Viejas), and on four reservations in Baja California (La Huerta, Nejí, San Antonio Nicuarr, and San José de la Zorra). The group living on a particular reservation is referred to as a "band," such as the "Viejas Band of Kumeyaay Indians."

Alfred L. Kroeber (1925:883) proposed that the population of the Kumeyaay in 1770, exclusive of those in Baja California, had been about 3,000. Katharine Luomala (1978:596) suggested that the region could have supported 6,000-9,000 Kumeyaay. Florence C. Shipek (1986:19) went much farther, estimating 16,000-19,000 inhabitants.

- Hualapai

The Hualapai (also spelled Walapai) live in the mountains of northwestern Arizona, United States. The name is derived from hwal, the Yuman word for pine, Hualapai meaning "people of the tall pine." Their traditional territory is a 100 mile (160 km) stretch along the pine-clad southern side of the Grand Canyon with the tribal capital located at Peach Springs.

- Havasupai

The Havasu ’Baaja (meaning the-people-of-the-blue-green-waters), or more commonly the Havasupai, are located in the northwestern part of the American state of Arizona. The tribe is well-known for being the only permanent inhabitants in the Grand Canyon, where they have lived for over 800 years. They are considered nomads, as they used to spend the summer and spring months in the canyon farming, while spending the winter and fall months on the plateau hunting.

In 1882, the U.S. government formed the Havasupai Indian Reservation which consisted of 518 acres (2.10 km²) of land inside the canyon. For 93 years they were confined to staying inside the canyon, which led to an increased reliance on farming and outside revenue tourism. In 1975, the U.S. Government reallocated 185,000 acres (750 km²) of land back to the Havasupai. The main "claim-to-fame" for the tribe is its richly colored waters and its awe-inspiring waterfalls, both of which have made this small community become a bustling tourist hub that attracts thousands of people every year.

- Yavapai

Yavapai (sometimes translated as mouthy, or talkative people, but generally translated as the sun people because they worshiped the sun, though many agree that it is a corruption of the Yuman word "Nyavkopai" - east people (Braatz 2003, 38) live in central Arizona. The Yavapai have much in common, linguistically and culturally, with their neighbors the Havasupai, the Hualapai, and the Athabascan Apache (Gifford 1936, 249). Yavapai often allied themselves with bands of Apache for raiding and were mistaken as Apache by settlers, being referred to Yavapai-Apache. Before the 1860s, when White settlers began exploring for gold in the area, the Yavapai occupied an area of approximately 20,000 mi² (51800 km²) bordering the San Francisco Peaks on the north, the Pinal Mountains on the east, and Martinez Lake and the Colorado River at the point where Lake Havasu is now on the west (Salzmann 1997, 58).

- Kiliwa and Paipai

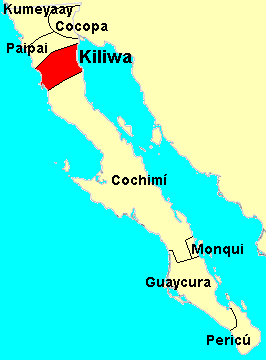

The Kiliwa and Paipai occupied a territory in Baja California lying between the Cochimí on the south and the Kumeyaay on the north.

Aboriginal Kiliwa subsistence was based on hunting and gathering of natural animal and plants rather than on agriculture. At least two dozen different plants were food resources, and many others were used for medicine or as materials for construction or craft products. Pit-roasted Agave (mescal; ječà) was the most important plant food. In the fall season, harvesting of acorns and pine nuts from the higher-elevation portions of Kiliwa territory was a major activity.

Rabbits and deer were the most important animal food sources, but a wide range of others were also hunted, including pronghorn antelope, bighorn sheep, medium-sized mammals such as mountain lions, many small mammal species, birds, reptiles, fish, and shellfish. Jackrabbits and quail were hunted communally, by being driven into nets. Treks were made to San Felipe on the east coast to harvest fish and shellfish and to collect salt.

Crop growing and stock raising were introduced during the historic period. Another highly valued food resource that was introduced during the historic period was wild honey.

The traditional material culture of the Kiliwa was not highly elaborate, as would be expected for a seasonally mobile group.

- Structures included semi-subterranean houses with willow poles and thatching, ramadas, and sweat houses.

- Hunting equipment included willow bows; arrows with carrizo reed shafts, wooden foreshafts, and stone points; wooden throwing sticks; and agave fiber nets.

- Processing equipment included manos and metates for grinding seeds, wooden drills and hearths for making fire, and pottery and basketry for cooking, storing, and transporting.

- Clothing was generally lacking for men. Women wore deer hid aprons and reed caps. Both sexes wore agave fiber sandals. Rabbitskin blankets provided warmth, and human hair capes were used in ceremonies. Cradles were used to transport infants.

Traditional leadership roles in communities and kin groups were held on a hereditary basis, but subject to an assessment of the individual leader's competence. Leaders' authority does not seem to have been extensive.

Kinship and community membership seems to have been defined to a large extent on the basis of patrilineal inheritance. Two levels of patrilineages (or clans, sibs) were recognized, corresponding to the šimułs of other western Yuman groups. Maselkwa were the smaller, more strongly localized groups. Several maselkwa might collectively constitute an ichiupu. On the broadest level, all Kiliwa were believed to be descended from four mythic brothers, the sons of the creator.

Social recreations included a variety of games: racing with balls, shinny, top spinning, archery, dice, a guessing game, and, most importantly, peón. Music was produced by singing and by instruments, including flutes, rattles, clappers, and bullroarers.

Shamans were believed to be able to effect magical cures of disease or injuries, or to cause them. They presided at some religious ceremonies, and they were thought to transform themselves into animals or birds and to bring rain.

Most documented Kiliwa ceremonies were linked to rites of passage in the lives of individuals:

- Birth involved various taboos or special requirements, but it was primarily a private family matter. The father observed a couvade.

- Boys' Initiation for groups of boys aged around 15 years was marked by the nose-piercing ceremony (mipípŭsá) and other activities extending over two months.

- Girls' Initiation at the time of first menstruation involved being baked in ashes for five days, washed in cold water for five days, and made to observe various prescriptions and taboos.

- Marriage involved little ceremony, other than the groom giving gifts to the bride's parents. Marrying up to two wives was permitted, and divorce was easy for either party.

- Death was the focus of the most elaborate Kiliwa ceremonies, occurring both immediately after an individual's death and as subsequent collective mourning observances. Talking to the dead and burning his possessions are among the formal actions.

The Jesuit missionary-explorer Wenceslaus Linck came overland from the south into the eastern part of Kiliwa territory in 1766. The expedition to establish Spanish settlements in California, led by Gaspar de Portolà and Junípero Serra passed through the western portions.

The Dominican mission of Santo Domingo was founded in Kiliwa territory near the coast in 1775. It was followed by an inland mission of San Pedro Mártir in 1794. By around the time of Mexican independence in 1821, the population at the Kiliwa missions had sharply declined.

In 1929, Meigs reported that only 36 adult Kiliwa were then living, primarily at three settlements around Arroyo León, at San Isidoro, and in Valle Trinidad. Twenty years later in 1949, Hohenthal found 30 adult Kiliwa living at four settlements, including Arroyo León, Agua Caliente, La Parra, and Tepí.

The Paipai (Pai pai, Pa'ipai, Akwa'ala, Yakakwal) lived in northern Baja California, Mexico. They occupied a territory lying between the Kiliwa on the south and the Kumeyaay and Cocopa on the north, and extending from San Vicente near the Pacific coast nearly to the Colorado River's delta in the east. Today they are concentrated primarily at the multi-ethnic community of Santa Catarina in Baja California's northern highlands.

Aboriginal Paipai subsistence was based on hunting and gathering of natural animal and plants rather than on agriculture. Numerous plants were exploited as food resources, notably including agave, yucca, mesquite, prickly pear, acorns, pine nuts, and juniper berries. Many other plants served as medicine or as material for construction or craft products. Animals used for food included deer, pronghorn antelope, bighorn sheep, rabbits, woodrats, various other medium and small mammals, quail, fish, and shellfish. Crop growing and stock raising were introduced during the historic period.

Paipai traditional material culture included structures (rectangular thatched-roof houses, ramadas, and probably sweathouses), equipment for hunting and warfare (bows, cane arrows, war clubs, nets), processing equipment (pottery, basketry, manos and metates, mortars and pestles, cordage, stone knives, awls), clothing (rabbitskin robes, fiber sandals; buckskin aprons and basketry caps for women), and cradles.

Kinship was based on patrilineal, patrilocal šimułs. It is not clear to what extent communities coincided with šimułs prehistorically; in historic times, community membership was quite fluid. The existence of any formal community leaders was denied by some; if they were present, their authority was probably not strong.

Social recreations included a variety of games: shinny, kickball races, the ring-and-pin game, dice, peon, archery, spinning tops, juggling, and cat's cradle. Music was produced by singing and by instruments that included flutes, gourd rattles, and jinglers. Pets were kept.

Shamans were believed to be able to cure disease or to cause it. They could also make or prevent rain. They acquired their powers through dreaming or by taking the hallucinogen Datura.

Among the most elaborated ceremonies were those relating to adolescence. Girls were initially individually roasted in pits and bathed, and later took part in group rites for several girls. Restrictions were applied during subsequent menstruation periods. Boys' puberty ceremonies involved nose-piercing, racing, and fasting.

Marriage was primarily at the couple's initiative and involved few formalities other than the payment of a bride price to the bride's parents. There is conflicting testimony as to whether or not polygyny and divorce were practiced.

There were prescriptions and taboos applied to both parents at the birth of a baby.

As with other Yuman groups, the greatest ceremonial elaboration seems to have been reserved for rites relating to funerals and the keruk mourning ceremony. The deceased was cremated and his property was destroyed.

Taboos were observed prior to hunting expeditions. There was also a taboo on a young man's eating of meat from his first kill.

The Dominican mission of San Vicente was founded near the coast in Paipai territory in 1780. It became a key center for the Spanish administration and military control of the region. In 1797 San Vicente was supplemented by an inland mission at Santa Catarina, near the boundary between Paipai and Kumeyaay territories. Mission Santa Catarina was destroyed in 1840 by hostile Indian forces, apparently including Paipai.

The main modern settlement of Paipai is at Santa Catarina, a community they share with Kumeyaay and Kiliwa residents.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Curtis, Edward S. [1908] 2007. The North American Indian Volume 2. Classic Books. ISBN 1404798021

- DuBois, Constance Goddard. 1908. Ceremonies and traditions of the Diegueño Indians" Journal of American Folk-lore XXI(82): 228-236. Retrieved September 10, 2008.

- Erdoes, Richard, and Alfonso Ortiz. 1985. American Indian Myths and Legends. New York, NY: Pantheon Books. ISBN 0394740181

- Halpern, A. M. 1997. Kar?úk: Native Accounts of the Quechan Mourning Ceremony. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 0520098188

- Hinton, Leanne, and Lucille J. Watahomigie (eds.). 1984. Spirit Mountain: An Anthology of Yuman Story and Song. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press, Tucson. ISBN 0816508178

- Luthin, Herbert W. 2002. Surviving through the Days. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 0520222709

- Waldman, Carl. 2006. Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes. New York, NY: Checkmark Books. ISBN 978-0816062744.

- Kroeber, A. L. [1925] 1976. Handbook of the Indians of California (Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 78). Dover Publications. ISBN 0486233685

- Yuma Reservation, California/Arizona United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 10, 2008.

- Spier, Leslie. [1933] 1978. Yuman Tribes of the Gila River. New York, NY: Dover Publications. ISBN 0486236110

- Bee, Robert L. Bee, and Frank W. Porter. 1989. The Yuma (Indians of North America). Chelsea House Publications. ISBN 1555467377

- Bee, Robert L. 1983. "Quechan." In Handbook of North American Indians. Vol. 10, Southwest, Alfonso Ortiz (ed.), 86-98. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 0160045797

- Garrigues, Lisa. 2008. Quechan elders take fight against casino resort to Washington Indian Country Today, August 12, 2008. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

- Fenger, Darin. 2007. Quechan filmmaker says he's grateful for blessings News From Indian Country, 5-27-07. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

- Waterman, T. T. 1910. Religious Practices of the Diegueño Indians. Retrieved September 16, 2008.

- Kelly, William H. 1977. Cocopa ethnography. Anthropological papers of the University of Arizona (No. 29). Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press. ISBN 0816504962

- Luomala, Katharine. 1978. "Tipai-Ipai." In California, edited by Robert F. Heizer, pp. 91-98. Handbook of North American Indians, William C. Sturtevant, general editor, vol. 8. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

- Shipek, Florence C. 1986. "The Impact of Europeans upon Kumeyaay Culture." In The Impact of European Exploration and Settlement on Location Native Americans, edited by Raymond Starr, pp. 13-25. Cabrillo Historical Association, San Diego.

- Braatz, Timothy. 2003. Surviving Conquest. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

- Gifford, Edward. 1936. Northeastern and Western Yavapai. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Salzmann, Zdenek, and Joy M. Salzmann. 1997. Native Americans of the Southwest: The Serious Traveler's Introduction to Peoples and Places. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. 0813322790

- Meigs, Peveril, III. 1939. The Kiliwa Indians of Lower California. Iberoamerica No. 15. University of California, Berkeley.

External links

- Fort Yuma-Quechan Tribe Inter-Tribal Council of Arizona

- Curtis, Edward S. 1908. The North American Indian

- The River Yuman People Native American Desert Peoples, DesertUSA.

- Gordon, Lynn. 1986. Maricopa syntax and morphology. (University of California publications in linguistics; 108). Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0520099656

- Cocopah Reservation, Arizona United States Census Bureau

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Yuman history

- Quechan history

- Quechan_traditional_narratives history

- Cocopah history

- Maricopa history

- Mohave history

- Kumeyaay history

- Hualapai history

- Havasupai history

- Yavapai_people history

- Kiliwa history

- Paipai history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.