Yan Zhenqing

| Other Names | |

|---|---|

| Courtesy Name: | Qingchen (清臣) |

| Alias: | Yan Pingyuan (顏平原) Yan Lugong (顏魯公) |

| Posthumous Name: | Wenzhong (文忠) |

Yan Zhenqing (Simplified Chinese: 颜真卿; Traditional Chinese: 顏真卿; pinyin: Yán Zhēnqīng; Wade-Giles: Yen Chench'ing, 709–785) was a leading Chinese calligrapher and a loyal governor of the Tang Dynasty. His artistic accomplishment in Chinese calligraphy parallels the greatest master calligraphers throughout the history, and his calligraphy style, Yan, is the textbook-style that every calligraphy lover has to imitate today.

Biography

Early life

Yan Zhenqing was born in Linyi of Shandong Province to a reputed academic family which served the court for many generations. His great-great grandfather Yan Shigu was a famous linguist while his father Yan Weizhen (顏惟貞) was Tang princes' private tutor and a great calligrapher himself. Under the influence of the family tradition and the strict instruction of his mother, Lady Yin (殷氏), Yan Zhenqing worked hard since his childhood and was well-read in literature and Confucianism.

In 734, at the age of 22, Yan Zhenqing qualified from the national wide imperial examination and was granted the title of Jinshi (a rough equivalent of the modern day doctoral degree). He then gained the rare opportunity of taking a special imperial examination that was set for candidates with extraordinary talents, again excelling in it. With outstanding academic background, Yan Zhengqing rose rapidly through the bureaucratic ladder: he was appointed vice-magistrate of Liquan District (醴泉尉), then later Investigating Censor (監察禦史) and Palace Censor (殿中侍禦史). His uprightness and outspoken style were hailed by the common people, but angered Grand Councilor Yang Guozhong; as a result, in 753, he was sent out of the capital as the governor of Pingyuan.

Civil war

By the time Yan Zhenqing took up the post of governor of Pingyuan, the An Lushan Rebellion was imminent. With his political sensitivity, Yan Zhenqing immediately started preparing for war by fortifying the city wall and stocking up provisions. He also sent emergency memorial to Emperor Xuanzong, but was ignored.

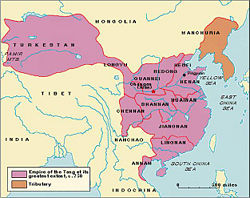

In December 755, An Lushan and Shi Siming (史思明) rebelled under the name of removing Yang Guozhong. The ill-prepared Tang government troops retreated with little resistance from all the prefectures in Heshuo (河朔) area (which includes the present day provinces of Shandong, Hebei and Henan); only Yan Zhenqing’s Pingyuan sustained through. He then combined force with his cousin, Yan Gaoqing (顏杲卿), who was the governor of Changshan (常山太守) (present day Quyang, Hebei), fighting the rebels at their rear. The government in its desperation, promoted Yan Zhenqing to Deputy Minister of Finance (戶部伺郎), and conferred him great military power to assist General Li Guangbi (李光弼) in the crackdown of the rebellion.

Thereafter Yans’ force won several major battles over the rebels, which include successfully cutting off their provision line and regaining control over seventeen commands in Heshuo area. In 756, Emperor Suzong ascended the throne and promoted Yan Zhenqing to Minister of Works (工部尚書). Due to poor military deployment by the Tang government, An Lushan managed to attack Hebei by surprise, and Yan Zhenqing reluctantly abandoned his command, returning to the court in 757. He was then appointed Minister of Law (刑部尚書), but his outspokenness against corruptive higher-ranking officials resulted himself being constantly demoted and re-promoted.

Late life

In 764, Emperor Daizong conferred the title of Duke of Lu (魯公) on Yan Zhenqing in recognition of his firm loyalty to the government and bravery during An Lushan Rebellion. However, his unbendable character was resented by the incumbent Grand Councilor, Lu Qi (盧杞), and cost him his life.

In 784, the military commissioner of Huaixi (淮西節度使), Li Xilie (李希烈), rebelled. Lu Qi had held a grudge against Yan Zhenqing for a long time, so he sent Yan Zhenqing to negotiate with Li Xilie in the hope that Yan Zhenqing will be killed. As expected, Li Xilie tried all means to coax or threaten Yan Zhenqing to surrender, but Yan Zhenqing was never wavered. According to the legend, Li Xilie set up a fire in the courtyard and told Yan Zhengqing he would be burnt to death if not surrendering. Yet Yan Zhenqing did not show the slightest fear and walked towards the fire determinately. Li Xilie could not help but to show respect to him, and in 785, Yan Zhenqing was secretly strangled in Longxing Temple (龍興寺) in Caizhou, Henan.

Upon hearing his death, Emperor Daizong closed the assembly for five days and conferred the posthumous title Wenzhong (文忠) on Yan Zhenqing. He was also widely mourned by the army and the people, and a temple was constructed to commemorate him. In Song Dynasty, the temple was moved to Shandong and henceforward became a key tourist attraction.

Calligraphy achievement

Yan Zhenqing is popularly held as the only calligrapher who parallelled Wang Xizhi, the "Calligraphy Sage." He specialized in kaishu (楷) Script and Cao (草) Script, though he also mastered other writings well. His Yan style of Kai Script, which brought Chinese calligraphy to a new realm, emphasized on strength, boldness and grandness. Like most of the master calligraphers, Yan Zhenqing learnt his skill from various calligraphers, and the development of his personal style can be basically divided into three stages.

Early period

Most calligraphers agree Yan Zhenqing’s early stage lasted until his 50s. During these years, Yan Zhenqing tried out different techniques and started to develop his personal genre. When he was young, he studied calligraphy under the famous calligraphers Zhang Xu and Chu Suiliang. Zhang Xu was skilled in Cao Script, which emphasizes the overall composition and flow; Chu Suiliang, on the other hand, was renowned for his graceful and refined Kai Script. Yan Zhenqing also drew inspiration from Wei Bei (魏碑) Style, which originated from Northern nomad minorities and focused on strength and simplicity.

In 752, he wrote one of his best-known pieces, Duobao Pagoda Stele (多寶塔碑). http://www.chinapage.com/calligraphy/yanzhenqing/duobao.html The stele has 34 lines, each containing 66 characters, and it was written for Emperor Xuanzong who was extremely pious to Buddhism at the moment. The style of the writing was close to that of the early Tang calligraphers, who emphasized elegance and "fancifulness"; yet it also pursues composure and firmness in the stroke of the brush, structuring characters on powerful frames with tender management on brushline.

Consolidating period

This period ranges from Yan Zhenqing’s fifties to sixty-five. During these years, he wrote some famous pieces like Guojia Miao Stele (郭傢廟碑) and Magu Shan Xiantan Ji (痲姑山仙墰記). Having experienced An Lushan Rebellion and frequent vicissitudes in his civil career, Yan Zhenqing’s style was maturing. He increased the waist force while wielding the brush, and blended the techniques from zhuan (篆) and li (隷) Scripts into his own style, making the start and ending of his brushline gentler. For individual stroke, he adopted the rule of “thin horizontal and thick vertical strokes”; strokes’ widths were varied to show the curvature and flow, and the dots and oblique strokes were finished with sharp edges. For character structure, Yan style displays squared shape and modest arrangement, with spacious center portion and tight outer strokes; this structure resembles more to the more dated Zhuan and Li Scripts. And for the allocation of the blank, characters are compact vertically, leaving relatively more space in between lines. Hence, the emerging Yan style had abandoned the sumptuous trend of early Tang calligraphers: it is rather upright, muscular, fitting, rich and controlled; than sloped, feminine, pretty, slim and capricious.

Consummating period

In the ten years’ before his death, Yan Zhenqing’s calligraphy accomplishment peaked. With established style, he continuously improved on each of his works, and completed his Magnum Opus, Yan Qingli Stele (顏勤禮碑). At this stage, he was able to fully exhibit his style at his will even through a single stroke, and under his modest and stately style bubbles the liveness and passion.

Influence

Yan Zhenqing’s style assimilated the essence of the past five hundred years, and almost all the calligraphers after him were more or less influenced by him. In his contemporary period, another great master calligrapher, Liu Gongquan, studied under him, and the much-respected Five-Dynasty Period calligrapher, Yang Ningshi (楊凝式) thoroughly inherited Yan Zhenqing’s style and made it bolder.

The trend of imitating Yan Zhenqing peaked during Song Dynasty. The "Four Grand Masters of Song Dynasty" – Su Shi, Huang Tingjian (黃庭堅), Mi Fu (米芾), Cai Xiang – all studied Yan Style; Su Shi even claimed Yan Zhenqing’s calligraphy "peerless" throughout the history.

After Song, the popularity of Yan Zhenqing declined slightly, as calligraphers tended to try out more abstract way of expression. However, it still took a very important status, and many renowned calligraphers, such as Zhao Mengfu and Dong Qichang (董其昌) are said to be inspired by Yan Zhenqing.

In contemporary China, the leading calligraphers like Sha Menghai (沙孟海) and Shen Yinmo conducted extended research on Yan style, and since then it regained its popularity. Nowadays almost every Chinese calligraphy learner imitates Yan style when he first picks up the brush, and Yan Zhenqing’s influence has also spread across oceans to Korea, Japan and South-east Asia.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Hucker, Charles O. (1985). A Dictionary of Official Titles in Imperial China. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-1193-3.

- Yao Jinming; Ed. Zhu Boxiong (1998). Zhong Guo Shu Hua Ming Jia Jing Pin Da Dian. Zhejiang Edu Press. ISBN 7-5338-2769-4.

- McNair, Amy. (1998). The Upright Brush: Yan Zhenqing's Calligraphy and Song Literati Politics. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-2002-9.

See also

- Chinese calligraphy

- Tang Dynasty art

- Tang Dynasty

- An Lushan Rebellion

External links

- Chinese Calligraphy: Images of steles and manuscripts

- Example part 1 and part 2

- Chinese Calligrpahy Introduction

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.