Woolly mammoth

| Woolly mammoth

| ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| Mammuthus primigenius Blumenbach, 1799 |

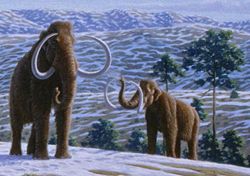

Woolly mammoth is the common name for an extinct elephant of the mammoth genus, Mammuthus primigenius, characterized by long, strongly curved tusks and hind legs much shorter than the forelegs, giving a slope to the back. It is also known as the tundra mammoth. Fossils of the woolly mammoth trace from about 250,000 years ago to 4,000 years ago (ANS; Vartanyan et al. 1995). This animal is known from bones and frozen carcasses from northern North America and northern Eurasia with the best preserved carcasses in Siberia.

Description

This mammoth species was first recorded in (possibly 150,000 years old) deposits of the second last glaciation in Eurasia. They were derived from steppe mammoths (Mammuthus trogontherii).[1]

It disappeared from most of its range at the end of the Pleistocene, with a dwarfed race still living on Wrangel Island until roughly 1700 B.C.E.[2]

Adaptations

Woolly mammoths had a number of adaptations to the cold, most famously the thick layer of shaggy hair, up to 50 cm (20 in) long, for which the woolly mammoth is named. They also had far smaller ears than modern elephants; the largest mammoth ear found so far was only 30 cm (12 in) long, compared to 180 cm (71 in) for an African elephant.

Their teeth were also adapted to their diet of coarse tundra grasses, with more plates and a higher crown than their southern relatives. Their skin was no thicker than that of present-day elephants, but unlike elephants they had numerous sebaceous glands in their skin which secreted greasy fat into their hair, improving its insulating qualities. They had a layer of fat up to 8 cm (3.1 in) thick under the skin which, like the blubber of whales, helped to keep them warm.

Woolly mammoths had extremely long tusks — up to 5 m (16 ft) long — which were markedly curved, to a much greater extent than those of elephants. It is not clear whether the tusks were a specific adaptation to their environment, but it has been suggested[attribution needed] that mammoths may have used their tusks as shovels to clear snow from the ground and reach the vegetation buried below. This is evidenced by flat sections on the ventral surface of some tusks. It has also been observed in many specimens that there may be an amount of wear on top of the tusk that would suggests some animals had a preference as to which tusk it rested its trunk on.

Extinction

Most woolly mammoths died out at the end of the Pleistocene, as a result of climate change and a shift in man's hunting patterns. A recent study conducted by the Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales in Spain determined that warming temperatures had reduced mammoth habitat to only a fraction of what it once was, putting the woolly mammoth population in sharp decline before the introduction of humans into the territory.[3] Glacial retreat shrunk mammoth habitat from 7,700,000 km² (3,000,000 sq mi) 42,000 years ago to 800,000 km² (310,000 sq mi) 6,000 years ago. Although a similarly drastic loss of habitat occurred at the end of the Saale glaciation 125,000 years ago, human pressure during the later warming period was sufficient to push the mammoth over the brink.[4] The study employed the use of climate models and fossil remains to make these determinations.[3]

A small population of woolly mammoths survived on St. Paul Island, Alaska, up until 6000 B.C.E.,[5] while another remained on Wrangel Island, located in the Arctic Ocean, up until 1700 B.C.E. Possibly due to their limited food supply, these animals were a dwarf variety, thus much smaller than the original Pleistocene woolly mammoth.[6] However, the Wrangel Island mammoths should not be confused with the Channel Islands Pygmy Mammoth, Mammuthus exilis, which was a different species.

Frozen Remains

The wooly mammoth is a common member in the fossil record, but unlike many others are often not actually converted to stone, but are actually preserved since their deaths. This is in part because of their massive size and partially because of the persistence of the frozen climate in which they had lived and, therefore, died.

The very first mammoth fossil fully documented by modern science, the Adams mammoth, was of this type, but had been allowed to largely decay before its recovery, possibly even having been partially devoured by modern wolves.[7]

Preserved frozen remains of woolly mammoths, with much soft tissue remaining, have been found in the northern parts of Siberia. This is a rare occurrence, essentially requiring the animal to have been buried rapidly in liquid or semi-solids such as silt, mud and icy water which then froze. This may have occurred in a number of ways. Mammoths may have been trapped in bogs or quicksands and either died of starvation or exposure, or drowning if they sank under the surface. Though judging by the evidence of undigested food in the stomach and seed pods still in the mouth of many of the specimens, neither starvation nor exposure seem likely. The maturity of this ingested vegetation places the time period in autumn rather than in spring when flowers would be expected.[8] The animals may have fallen through frozen ice into small ponds or potholes, entombing them. Many are certainly known to have been killed in rivers, perhaps through being swept away by river floods. In one location, by the Berelekh River in Yakutia in Siberia, more than 9,000 bones from at least 156 individual mammoths have been found in a single spot, apparently having been swept there by the current.[citation needed]

In 1977, the well-preserved carcass of a 7- to 8-month old baby woolly mammoth, named "Dima", was discovered. This carcass was recovered from permafrost on a tributary of the Kolyma River in northeastern Siberia. This baby woolly mammoth weighed approximately 100 kg (220 lb) at death and was 104 cm (41 in) high and 115 cm (45 in) long. Radiocarbon dating determined that Dima died about 40,000 years ago. Its internal organs are similar to those of living elephants, but its ears are only one-tenth the size of those of an African elephant of similar age.[1]

In the summer of 1997, a Dolgan family named Jarkov discovered a piece of mammoth tusk protruding from the tundra of the Taymyr Peninsula in Siberia, Russia. In September/October 1999 this 20,380-year-old carcass and the surrounding sediment were flown to an ice cave in Khatanga, Taymyr Autonomous Okrug. In October 2000, the careful defrosting operations in this cave began with the use of hairdryers to keep the hair and other soft tissues intact.[9][10]

To date, thirty-nine preserved bodies have been found, but only four of them are complete. In most cases the flesh shows signs of decay before its freezing and later desiccation. Stories abound about frozen mammoth carcasses that were still edible once defrosted, but the original sources indicate that the carcasses were in fact terribly decayed, and the stench so unbearable that only the dogs accompanying the finders showed any interest in the flesh.[11]

In addition to frozen carcasses, large amounts of mammoth ivory have been found in Siberia. Mammoth tusks have been articles of trade for at least 2,000 years.[citation needed] They have been and are still a highly prized commodity. Güyük, the 13th century Khan of the Mongols, is reputed to have sat on a throne made from mammoth ivory,[citation needed] and even today it is in great demand as a replacement for the now-banned export of elephant ivory.

Genetics

Since there is a known case in which an Asian elephant and an African elephant have produced a live (though sickly) offspring, it has been theorized that if mammoths were still alive today, they would be able to interbreed with Indian elephants. This has led to the idea that perhaps a mammoth-like beast could be recreated by taking genetic material from a frozen mammoth and combining it with that from a modern Indian elephant.

Scientists hope to retrieve the preserved reproductive organs of a frozen mammoth and revive its sperm cells. However, not enough genetic material has been found in frozen mammoths for this to be attempted. The complete mitochondrial genome sequence of Mammuthus primigenius has been determined, however.[12] The analysis demonstrates that the divergence of mammoth, African elephant, and Asian elephant occurred over a short time, and confirmed that the mammoth was more closely related to the Asian than to the African elephant. As an important landmark in this direction, in December 2005, a team of American, German, and UK researchers were able to assemble a complete mitochondrial DNA of the mammoth, which allowed them to trace the close evolutionary relationship between mammoths and the Asian elephant. African elephants branched away from the woolly mammoth around 6 million years ago, a moment in time close to that of the similar split between chimps and humans. Many researchers expect that the first fully sequenced nuclear genome of an extinct species will be that of the mammoth.

On July 6 2006 it was reported that scientists extracted a mammal hair colour gene called Mc1r from a 43,000-year old woolly mammoth bone from Siberia.[13]

Cryptozoology

There have been occasional claims that the woolly mammoth is not actually extinct, and that small isolated herds might survive in the vast and sparsely inhabited tundra of the northern hemisphere. In the late nineteenth century, there were, according to Bengt Sjögren (1962), persistent rumours about surviving mammoths hiding in Alaska.[14] In October 1899, a story about a man named Henry Tukeman detailed his having killed a mammoth in Alaska and that he subsequently donated the specimen to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. However, the museum denied the existence of any mammoth corpse and the story turned out to be a hoax.[15] Sjögren (1962) believes the myth was started when the American biologist Charles Haskins Townsend traveled in Alaska, saw Eskimos trading mammoth tusks, asked if there still were living mammoths in Alaska and provided them with a drawing of the animal.

In the 19th century, several reports of "large shaggy beasts" were passed on to the Russian authorities by Siberian tribesman, but no scientific proof ever surfaced. A French charge d´affaires working in Vladivostok, M. Gallon, claimed in 1946 that in 1920 he met a Russian fur-trapper that claimed to have seen living giant, furry "elephants" deep into the taiga. Gallon added that the fur-trapper didn't even know about mammoths before, and that he talked about the mammoths as a forest-animal at a time when they were seen as living on the tundra and snow.[14]

In legends

A mammoth possibly appears in an ancient legend of the Kaska tribe in British Columbia, The Bladder Headed Boy. The story tells how the boy in the title killed the animal, and was rewarded by being made the first chief of his people. The animal is described as a "huge shaggy beast that roamed the land long ago," but is also said to steal meat and eat people, suggesting that the creature in the story could have become embellished over the years, or refers to some animal other than a mammoth.[16]

A traditional Inuit string figure is said to represent a large prehistoric beast, often identified with the mammoth.[17]

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Academy of Natural Sciences (ANS). n.d. Woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius). Academy of Natural Sciences. Retrieved May 15, 2008.

- Capelli, C., R. D. E. MacPhee, A. L. Roca, F. Brisighelli, N. Georgiadis, S. J. O'Brien, J. Stephen , and A. D. Greenwood. 2006. A nuclear DNA phylogeny of the woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 40(2): 620–627. Retrieved May 15, 2008.

- Dmitry, S. 2007. Baby mammoth find promises breakthrough. Reuters July 11, 2007. Retrieved May 15, 2008.

- Illinois Department of Natural Resources (IDNR). 2006. Recently discovered 11-foot long woolly mammoth tusk on display at the Illinois State Museum. Illinois Department of Natural Resources Press Release August 14, 2006. Retrieved May 15, 2008.

- Rincon, P. 2007. Baby mammoth discovery unveiled. BBC July 10, 2007. Retrieved May 14, 2008.

- Schirber, M. 2004. Surviving extinction: Where woolly mammoths endured. Live Science. Retrieved May 15, 2008.

- Vartanyan, S. L., Kh. A. Arslanov, T. V. Tertychnaya, and S. B. Chernov. 1995. Radiocarbon dating evidence for mammoths on Wrangel Island, Arctic Ocean, until 2000 B.C.E.. Radiocarbon 37(1): 1-6. Retrieved May 15, 2008.

External links

- Has anybody ever eaten the meat of a frozen mammoth?, Stupid Question, February 14, 2005, by John Ruch.

[[Category:Animals]

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Yukon Beringia Interpretive Centre - Woolly Mammoth. www.beringia.com. Retrieved 2008-03-12. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Harington" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Nowak, Ronald M. (1999). Walker's Mammals of the World. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0801857899.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Nogués-Bravo, D. and Rodríguez, J.; Hortal, J.; Batra, P.; Araújo, M. B. (2008). Climate Change, Humans, and the Extinction of the Woolly Mammoth. PLoS Biology 6 (4): e79.

- ↑ Sedwick, Caitlin (2008). What Killed the Woolly Mammoth?. PLoS Biology 6 (4): e99.

- ↑ Guthrie, R. Dale (2004). Radiocarbon evidence of mid-Holocene mammoths stranded on an Alaskan Bering Sea island. Nature 429: 746-749.

- ↑ Vartanyan, S. L. and Garutt, V. E.; Sher, A. V. (1993). Holocene dwarf mammoths from Wrangel Island in the Siberian Arctic. Nature 362: 337-349.

- ↑ (2005). "Mammouth - from their discovery and how to bring them the life". Paper from the NATHIST annual meeting in Jakobstad.

- ↑ E. W. Pfizenmayer was one of the scientists who recovered and studied the mammoth that was found at the river Berezovka in the early 1900s. He wrote: “Its death must have occurred very quickly after its fall, for we found half-chewed food still in its mouth, between the back teeth and on its tongue, which was in good preservation. The food consisted of leaves and grasses, some of the latter carrying seeds. We could tell from these that the mammoth must have come to its miserable end in the autumn.” See Pfizenmayer, E. W. (1939). Siberian Man and Mammoth. London: Blackie and Son.

- ↑ Mol, D. et al. (2001). The Jarkov Mammoth: 20,000-Year-Old carcass of a Siberian woolly mammoth Mammuthus primigenius (Blumenbach, 1799). The World of Elephants, Proceedings of the 1st International Congress (October 16-20 2001, Rome): 305-309. Full text pdf

- ↑ Debruyne, Régis and et al. (2003). Mitochondrial cytochrome b of the Lyakhov mammoth (Proboscidea, Mammalia): new data and phylogenetic analyses of Elephantidae. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 26 (3): 421-434.

- ↑ Farrand, William R. (1961). Frozen Mammoths and Modern Geology: The death of the giants can be explained as a hazard of tundra life, without evoking catastrophic events. Science 133: 729-735.

- ↑ Krause, J. and et al. (2006). Multiplex amplification of the mammoth mitochondrial genome and the evolution of Elephantidae. Nature 439: 724-727.

- ↑ Römpler, H. and et al. (2006). Nuclear Gene Indicates Coat-Color Polymorphism in Mammoths. Science 313 (5783): 62.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Sjögren, Bengt. Farliga djur och djur som inte finns, Prisma, 1962

- ↑ Murray, Morgan. Henry Tukeman: Mammoth's Roar was Heard All The Way to the Smithsonian. www2.tpl.lib.wa.us. Retrieved 2008-01-17.

- ↑ Legends of the Kaska First Nations: “Bladder-Head Boy”.. www.folklore.bc.ca. Retrieved 2008-01-17.

- ↑ Paterson, T. T. (1949). Eskimo String Figures and Their Origin. Acta Arctica 3: 1-98.