Tlingit

| Tlingit |

|---|

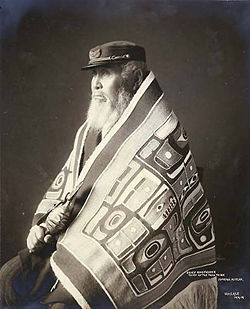

Chief Anotklosh of the Taku Tribe, ca. 1913 |

| Total population |

| 11,000 |

| Regions with significant populations |

| USA (Alaska), Canada (British Columbia, Yukon) |

| Languages |

| English, Tlingit |

| Religions |

| Christianity, other |

The Tlingit (IPA: /'klɪŋkɪt/, also /-gɪt/ or /'tlɪŋkɪt/ which is often considered inaccurate) are an Indigenous people. Their name for themselves is Lingít (/ɬɪŋkɪt/) , meaning "people." The Russian name Koloshi (from an Aleut term for the labret) or the related German name Koulischen may be encountered in older historical literature.

The Tlingit are a matrilineal society who developed a complex hunter-gatherer culture in the temperate rainforest of the southeast Alaska coast and the Alexander Archipelago. The Tlingit language is well known not only for its complex grammar and sound system but also for using certain phonemes which are not heard in almost any other language.

Territory

The maximum territory historically occupied by the Tlingit extended from the Portland Canal along the present border between Alaska and British Columbia north to the coast just southeast of the Copper River delta. The Tlingit occupied almost all of the Alexander Archipelago except the southernmost end of Prince of Wales Island and its surroundings into which the Kaigani Haida moved just before the first encounters with European explorers. Inland the Tlingit occupied areas along the major rivers which pierce the Coast Mountains and Saint Elias Mountains and flow into the Pacific, including the Alsek, Tatshenshini, Chilkat, Taku, and Stikine rivers. With regular travel up these rivers the Tlingit developed extensive trade networks with Athabascan tribes of the interior, and commonly intermarried with them. From this regular travel and trade, a few relatively large populations of Tlingit settled around the Atlin, Teslin, and Tagish lakes, the headwaters of which flow from areas near the headwaters of the Taku River.

Delineating the modern territory of the Tlingit is complicated by the fact that they are spread across the border between the United States and Canada, by the lack of designated reservations, other complex legal and political concerns, and a relatively high level of mobility among the population. In Canada, the modern communities of Atlin, British Columbia (Taku River Tlingit), Teslin, Yukon (Teslin Tlingit Council), and Carcross, Yukon (Carcross/Tagish First Nation) have reserves and are the representative Interior Tlingit populations. The territory occupied by the modern Tlingit people in Alaska is however not restricted to particular reservations, unlike most tribes in the contiguous 48 states. This is the result of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) which established regional corporations throughout Alaska with complex portfolios of land ownership rather than bounded reservations administered by tribal governments. The corporation in the Tlingit region is Sealaska, Inc. which serves the Tlingit as well as the Haida in Alaska. Tlingit people as a whole participate in the commercial economy of Alaska, and as a consequence live in typically American nuclear family households with private ownership of housing and land. Many also possess land allotments from Sealaska or from earlier distributions predating ANCSA. Despite the legal and political complexities, the territory historically occupied by the Tlingit can be reasonably designated as their modern homeland, and Tlingit people today envision the land from around Yakutat south through the Alaskan Panhandle and including the lakes in the Canadian interior as being Lingít Aaní, the Land of the Tlingit.

The extant Tlingit territory can be roughly divided into four major sections, paralleling ecological, linguistic, and cultural divisions. The Southern Tlingit occupy the region south of Frederick Sound, and live in the northernmost reaches of the Western Redcedar forest. North of Frederick Sound to Cape Spencer, and including Glacier Bay and the Lynn Canal, are the Northern Tlingit, who occupy the warmest and richest of the Sitka Spruce and Western Hemlock forest. The Interior Tlingit live along the large interior lakes and the drainage of the Taku River, and subsist in a manner similar to their Athabascan neighbors in the mixed spruce taiga. North of Cape Spencer, along the coast of the Gulf of Alaska to Controller Bay and Kayak Island, are the Gulf Coast Tlingit, who live along a narrow strip of coastline backed by steep mountains and extensive glaciers, and battered by Pacific storms. The trade and cultural interactions between each of these Tlingit groups and their disparate neighbors, the differences in food harvest practices, and the dialectical differences contribute to these identifications which are also supported by similar self-identifications among the Tlingit.

Culture

The Tlingit culture is multifaceted and complex, a characteristic of Northwest Pacific Coast peoples with access to easily exploited rich resources. In Tlingit culture a heavy emphasis is placed upon family and kinship, and on a rich tradition of oratory. Wealth and economic power are important indicators of status, but so is generosity and proper behavior, all signs of "good breeding" and ties to aristocracy. Art and spirituality are incorporated in nearly all areas of Tlingit culture, with even everyday objects such as spoons and storage boxes decorated and imbued with spiritual power and historical associations.

The culture of the Tlingit, an Indigenous people from Alaska, British Columbia, and the Yukon, is multifaceted and complex, a characteristic of Northwest Pacific Coast peoples with access to easily exploited rich resources. In Tlingit culture a heavy emphasis is placed upon family and kinship, and on a rich tradition of oratory. Wealth and economic power are important indicators of status, but so is generosity and proper behavior, all signs of "good breeding" and ties to aristocracy. Art and spirituality are incorporated in nearly all areas of Tlingit culture, with even everyday objects such as spoons and storage boxes decorated and imbued with spiritual power and historical associations.

The Tlingit kinship system, like most Northwest Coast societies, is based on a matrilineal structure, and describes a family roughly according to Morgan's Crow system of kinship. The society is wholly divided into two distinct moieties, termed Raven (Yéil) and Eagle/Wolf (Ch'aak'/Ghooch). The former identifies with the raven as its primary crest, but the latter is variously identified with the wolf, the eagle, or some other dominant animal crest depending on location; occasionally this moiety is simply called the "not Raven" people. There is a general tendency among younger Tlingits towards identifying all Eagle/Wolf clans with eagle in preference to wolf or other crests, something which is deprecated by most elders but is reinforced by the modern associations of Tlingit with their Tsimshian and Haida neighbors. Members of one moiety traditionally may only marry a person of the opposite moiety, however in the last century this system began to break down and today so-called "double-eagle" and "double-raven" marriages are common, as well as marriages with non-Tlingit people. There is no word in Tlingit which refers to moiety, since referring to a particular person by their clan membership (see below) is enough to determine their moiety affiliation. In colloquial English the term "side" is often used among the Tlingit since "moiety" is a specialized term unfamiliar to most.

The moieties provide the primary dividing line across Tlingit society, but identification is rarely made with the moiety. Instead individuals identify with their matrilineal clan (naa), a large group of people related by shared genealogy, history, and possessory rights. Clan sizes vary widely, and some clans are found throughout all the Tlingit lands whereas others are found only in one small cluster of villages. The Tlingit clan functions as the main property owner in the culture, thus almost all formal property amongst the Tlingit belongs to clans, not to individuals. Due to the decline in traditional knowledge among the younger generations, many young urban Tlingit people are uncertain of their exact clan affiliation, and may simply refer to themselves by one or the other moiety. If they become more familiar with traditional cultural practice they either discover and research their clan or are formally adopted into an appropriate clan in the area.

Because of the heavy emphasis on clan and matrilineality the father played a relatively minor role in the lives of his children. Instead, what Europeans would consider the father's primary role was filled by the mother's brother, the children's maternal uncle, who was of the same clan as the children. This man would be the caretaker and teacher of the children, as well as the disciplinarian. The father had a more peripheral relationship with the children, and as such many Tlingit children have very pleasant memories of their fathers as generous and playful, while they maintain a distinct fear and awe of their maternal uncles who exposed them to hard training and discipline.

Beneath the clans are houses (hít), smaller groups of people closely related by family, and who in earlier times lived together in the same large communal house. The physical house itself would be first and foremost property of the clan, but the householders would be keepers of the house and all the material and nonmaterial goods associated with it. Each house was led by a "chief," in Tlingit hít s'aatí "house master," an elder male (or less often a female) of high stature within the family. Hít s'aatí who were recognized as being of particularly high stature in the community, to the point of being major community leaders, were called aan s'aatí or more often aankháawu, "village master" or "village leader." The term aan s'aatí is now used to refer to an elected city mayor in Tlingit, although the traditional position was not elected and did not imply some coercive authority over the residents.

The existence of a "chief" for every house lineage in a village confused many early European explorers and traders who expected a single autocratic "chief" in a given village or region. This led to numerous confrontations and skirmishes among the Europeans and Tlingit in early history, since a particular "chief" could only hold sway over members of his own household and not over others in the village. A high stature hít s'aatí could convince unrelated villagers to behave a certain way, but if he lost significant status the community would begin to ignore him, much to the dismay of Europeans who were depending on his authority.

The hít s'aatí is usually the caretaker and administrator of house property, as well as some or most clan property in his region. He may often refer to himself as the "slave" of clan and house valuables and regalia because his position is not one of true ownership. Instead the position is more like that of a museum curator, one who has some say in whether or not a particular item is to be used or displayed, but who does not truly own that item and who may not dispense with it, sell it, or destroy it without the consultation of other family members. The hít s'aatí is also responsible for seeing the clan regalia brought out regularly at potlatches where the value and history of these items may be reconfirmed through ceremonial use and payments to the opposite clans. The funds for these potlatches may come primarily from the hít s'aatí, and as such the regalia which represent his ancestors can be seen as spending his money for him.

Historically, marriages amongst Tlingits and occasionally between Tlingits and other tribes were arranged. The man would move into the woman's house and become a member of that household, where he would contribute towards communal food gathering and would have access to his wife's clan's resources. Because the children would be of the mother's clan, marriages were often arranged such that the man would marry a woman who was of the same clan as his own father, though not a close relation. This constituted an ideal marriage in traditional Tlingit society, where the children were of the same clan as their paternal grandfather and could thus inherit his wealth, prestige, names, occupation, and personal possessions.

Because often the grandparents, particularly grandfathers, had a minimal role in the upbringing of their own children, they took an active interest in the upbringing of their grandchildren, and are noted for doting upon them beyond reason. This is usually exemplified by the story of Raven stealing daylight from his putative grandfather, who gave him the moon and the stars, and despite losing both of them to Raven's treachery, gave him the sun as well simply because he was a favored grandchild.

Any Tlingit is a member of a clan, be it by birth or adoption. Many Tlingits are children of another clan, the clan of their fathers. The relationship between father and child is warm and loving, and this relationship has a strong influence on the relation between the two clans. During times of grief or trouble the Tlingit can call on his father's clan for support at least as much as he can call on his own. His father's clan is not obliged to help him, but the familial connection can be strong enough to alienate two clans in the same moiety. This situation is well documented in oral history, where two clans of opposite moieties are opposed in war—one clan may call upon a related clan of the same moiety for assistance only to be refused because of a father's child among its enemies.

The opposition of clans is also a motivator for the reciprocal payments and services provided through potlatches. Indeed, the institution of the potlatch is largely founded on the reciprocal relationship between clans and their support during mortuary rituals. When a respected Tlingit dies the clan of his father is sought out to care for the body and manage the funeral. His own clan is incapable of these tasks due to grief and spiritual pollution. The subsequent potlatches are occasions where the clan honors its ancestors and compensates the opposite clans for their assistance and support during trying times. This reciprocal relationship between two clans is vital for the emotional, economic, and spiritual health of a Tlingit community.

In Tlingit society many things are considered property which are not in European societies. This includes names, stories, speeches, songs, dances, landscape features (e.g. mountains), and artistic designs. Note that these notions of property are similar to those considered under modern intellectual property law. More familiar property objects are buildings, rivers, totem poles, berry patches, canoes, and works of art. The Tlingit have long felt powerless to defend their cultural properties against depredation by opportunists, but have in recent years become aware of the power of American and Canadian law in defending their property rights and have begun to prosecute people for willful theft of such things as clan designs.

It is important to note that in modern Tlingit society two forms of property are extant. The first and foremost is unavoidably that of the American and Canadian cultures, and is rooted in European law. The other is the Tlingit concept of property as described here. The two are contradictory in terms of rightful ownership, inheritance, permanence, and even in the very idea of what can be owned. This is the cause of many disagreements both within the Tlingit and with outsiders, as both concepts can seem to be valid at the same time. The Tlingit apply the indigenous concept of property mostly in ceremonial circumstances, such as after the death of an individual, the construction of clan houses, erection of totem poles, etc. The situation of death can be problematic however since Tlingit law dictates that any personal property reverts to clan ownership in the absence of any clan descendants who can serve as caretakers. This of course contradicts the European legal interpretation which claims that property reverts to the state in the absence of legal heirs. However, the two may be considered to be consistent, in that the clan serves as the essence of a Tlingit concept of state. Obviously such matters require careful consideration by both Tlingit familiar with the traditional laws and by the governments involved.

A myriad of art forms are considered property in Tlingit culture. The idea of copyright applied to Tlingit art is inappropriate, since copyright is generally restrictive to particular works or designs. In Tlingit culture, the ideas behind artistic designs are themselves property, and their representation in art by someone who cannot prove ownership is an infringement upon the property rights of the proprietor.

Stories are considered property of particular clans. Some stories are shared freely but are felt to belong to a particular clan, other stories are clearly felt to be restricted property and may not be shared without a clan member's permission. Certain stories are however essentially felt to be in the public domain, such as many of the humorous tales in the Raven cycle. The artistic representation of characters or situations from stories which are known property of certain clans is an infringement upon the clan's property rights to that story.

Songs are also considered to be property of clans, however since songs are more frequently composed than stories, a clear connection to individuals is felt until that individual dies at which point the ownership tends to revert to the clan. A number of children's songs or songs sung to children, commonly called 'lullabies', are considered to be in the public domain. However, any song written with a serious intent, be it a love song or a song of mourning, is considered to be the sole property of the owner and may not be sung, recorded, or performed without that clan's permission.

Dances are also considered to be clan property, along the same lines as songs. Since people from different clans are often involved in the performance of a dance, it is considered essential that before the dance is performed or the song sung that a disclaimer be made regarding who permission was obtained from, and with whom the original authorship or ownership rests.

Names are property of a somewhat different kind. Most names are inherited, that is they are taken from a deceased relative and applied to a living member of the same clan. However, children are not necessarily given an inherited name while young, instead being given one that seems appropriate to the child, recalls an interesting event in the child's life, or is simply made up on the spot. These names, lacking a strong history, are not considered to be as important as those which have been passed on through many generations, and as such are not so carefully defended. Also, some names are 'stolen' from a different clan to make good on an unpaid obligation or debt, and returned when the debt is paid or else passed down through the new clan until it can make a stable claim to ownership of the name.

Places and resources are also considered property, though in a much less clearly defined way than is found in the European legal tradition. Locations are not usually clearly bounded in the Tlingit world, and although sometimes certain landmarks serve as clear boundary markers, ownership of places is usually correlated with a valuable resource in that location rather than overt physical characteristics. Usually the resources in question are food sources, such as salmon streams, herring spawning grounds, berry patches, and fishing holes. However, they are not always immediately apparent, such as the ownership of mountain passes by some clans which is due to exclusive trading relationships with Athabascans living in lands accessible by those passes.

Although clan ownership of places is nearly complete in the Tlingit world, with the entirety of Southeast Alaska being divided up into a patchwork of bays, inlets, and rivers belonging to particular clans, this does not in practice provide much of an obstacle to food harvest and travel. Reciprocal relationships between clans guarantee permission for free harvest in most areas to nearly any individual, and since the level of interclan disagreements has declined the attitude towards resource ownership is now at a point where few will persecute tresspass into clan areas as long as the individuals involved show respect and restraint in their harvest. Note that this only pertains to relations within Tlingit society, and not to relations with the American and Canadian governments or with non-Tlingit individuals.

Before 1867 the Tlingit were avid practitioners of slavery. The outward wealth of a person or family was roughly calculated by the number of slaves held. Slaves were taken from all peoples that the Tlingit encountered, from the Aleuts in the west, the Athabascan tribes of the interior, and all of the many tribes along the Pacific coast as far south as California. Slaves were bought and sold in a barter economy along the same lines as any other trade goods. They were often ceremonially freed at potlatches, the giving of freedom to the slave being a gift from the potlatch holder. However, they were just as often ceremonially killed at potlatches as well, to demonstrate economic power or to provide slaves for dead relatives in the afterlife. Treatment of slaves seems to have differed from individual to individual, and both stories and historical records give examples of slaves being treated very kindly as well as very cruelly.

Since slavery was an important economic activity to the Tlingit, it came as a tremendous blow to the society when emancipation was enforced in Alaska after its purchase by the United States from Russia. This forced removal of slaves from the culture incensed many Tlingit who were not so disturbed by its outlawing as much as by the fact that they were not repaid for their loss of property. In a move traditional against those with unpaid debts, a totem pole was erected that would shame the Americans for not having paid back the Tlingits for their loss, and at its top for all to see was a very carefully executed carving of Abraham Lincoln, whom the Tlingits were told was the person responsible for freeing the slaves. This has since been frequently misinterpreted as intending to honor Lincoln, but it was in fact done as a way to shame the US government into repaying the Tlingits for a profound loss of wealth.

Potlaches (Tl. koo.éex' ) were held for deaths, births, naming, marriages, sharing of wealth, raising totems, special events, honoring the leaders or the departed.

The memorial potlatch is a major feature of Tlingit culture. A year or two following a person's death this potlatch was held to restore the balance of the community. Members of the deceased family were allowed to stop mourning. If the deceased was an important member of the community, like a chief or a shaman for example, at the memorial potlatch his successor would be chosen. Clan members from the opposite moiety took part in the ritual by receiving gifts and hearing and performing songs and stories. The function of the memorial potlatch was to remove the fear from death and the uncertainty of the afterlife.

Art

{{#invoke:Message box|ambox}}

The Tlingit carved crests on totem poles that were made of cedar trees. Their culture was largely based on reverence towards the native american totem animals, and the finely detailed craftsmanship of woodworking depicts their spirituality through art. Traditional colors for the decorative art of the Tlingit were generally greens, blues and reds, which can make their works easily recognizable to the lay person. Spirits and creatures from the natural world were often believed to be one and the same, and were uniquely depicted with varying degrees of realism. The Tlingit used stone axes, drills, adzes and different carving knives to craft their works, which were generally made out wood, although precious metals such as silver and copper were not uncommon mediums for Tlingit art, as well as the horns of animals.

Posts in the house which divided the rooms were ornately carved with family crests, as well as gargoyle-like figures to ward off evil spirits. Great mythology and legend was associated with each individual totem, often telling a story about the ancestry of the household, or a spiritual account of a famous hunt.

Food

Food is a central part of Tlingit culture, and the land is an abundant provider. A saying amongst the Tlingit is that "when the tide goes out the table is set." This refers to the richness of intertidal life found on the beaches of Southeast Alaska, most of which can be harvested for food. Another saying is that "in Lingít Aaní you have to be an idiot to starve." Since food is so easy to gather from the beaches, a person who can't feed himself at least enough to stay alive is considered to be a fool, perhaps mentally incompetent or suffering from very bad luck. However, though eating off the beach would provide a fairly healthy and varied diet, eating nothing but "beach food" is considered contemptible among the Tlingit, and a sign of poverty. Indeed, shamans and their families were required to abstain from all food gathered from the beach, and men might avoid eating beach food before battles or strenuous activities in the belief that it would weaken them spiritually and perhaps physically as well. Thus for both spiritual reasons as well as to add some variety to the diet, the Tlingit harvest many other resources for food besides those which are easily found outside their front doors. No other food resource receives as much emphasis as salmon, however seal and game are both close seconds.

The food of the Tlingit, an Indigenous people from Alaska, British Columbia, and the Yukon, is a central part of Tlingit culture, and the land is an abundant provider. A saying amongst the Tlingit is that "when the tide goes out the table is set." This refers to the richness of intertidal life found on the beaches of Southeast Alaska, most of which can be harvested for food. Another saying is that "in Lingít Aaní you have to be an idiot to starve." Since food is so easy to gather from the beaches, a person who can't feed himself at least enough to stay alive is considered to be a fool, perhaps mentally incompetent or suffering from very bad luck. However, though eating off the beach would provide a fairly healthy and varied diet, eating nothing but "beach food" is considered contemptible among the Tlingit, and a sign of poverty. Indeed, shamans and their families were required to abstain from all food gathered from the beach, and men might avoid eating beach food before battles or strenuous activities in the belief that it would weaken them spiritually and perhaps physically as well. Thus for both spiritual reasons as well as to add some variety to the diet, the Tlingit harvest many other resources for food besides those which are easily found outside their front doors. No other food resource receives as much emphasis as salmon, however seal and game are both close seconds.

A particular problem with the Tlingit diet is ensuring enough vitamins and minerals are available. Protein is ubiquitous. Iodine from saltwater life is easily obtained, but important dietary components such as calcium, vitamin D, vitamin A, and vitamin C, are lacking in meat and fish. To ensure that such essentials are available, the Tlingit eat almost all parts of animals which they harvest. Bones used for soup stock provide leached calcium, as do ground calcined shells. Vitamin A is obtained from livers. Vitamin C is primarily found in berries and some other plants, such as skunk cabbage leaves. Bone marrow provides valuable iron and vitamin D. Intestines and stomachs are harvested to provide vitamin E and the B complexes.

Today most Tlingit eat a number of packaged products as well as imported staples such as dairy products, grains, beef, pork, and chicken. In the larger towns most of the American restaurant standards are available, such as pizza, Chinese food, and delicatessen goods. Ice cream and SPAM are particularly popular. Rice (koox) has long been a staple, as have pilot crackers (gháatl), and both have specific terms in Tlingit which are adapted from now uneaten foods (Kamchatka lily and a type of tree fungus).

The primary staple of the Tlingit diet, Salmon was traditionally caught using a variety of methods. The most common being the fishing weir or trap to restrict movement upstream. These traps allowed hunters to easily spear a good amount of fish with little effort. It did, however, required extensive cooperation between the men fishing and the women on the shore doing the cleaning.

Fish traps were constructed in a few ways, depending on the type of river or stream being worked. At the mouth of a smaller stream wooden stakes were driven in rows into the mud in the tidal zone. The stakes would be used to support a weir constructed from flexible branches. Outside the harvest the weir would be removed but the stakes left behind; archaeological evidence has uncovered a number of sites where long rows of sharpened stakes were hammered into the gravel and mud.

Another trap for smaller streams was made using rocks piled to form long, low walls. These walls would be submerged at high tide and the salmon would swim over them. Adults and children would throw rocks beyond the wall when the tide began receding, scaring the fish into staying inside the wall. Once the tide went down enough to expose the wall, men would walk out on the wall to spear the schooling salmon. The remnants of these walls are still visible at the mouths of many streams; although none are in use today elders recall them being used in the early twentieth century.

On larger rivers a weir would be built which spanned the entire width of the river or merely crossed a channel known to be used by salmon. These weirs followed the pattern above, but instead of depending on the tide to fill them, they had small gaps in the weir with platforms above them. Since salmon were restricted to passage through these small gaps they were easy targets for the spearmen who plucked them from their platforms above the gaps.

Fishwheels, though not traditional, came into use in the late nineteenth century. The mechanism was based on a floating platform which could be tied off to a tree on the bank of a river. The wheel consisted of two or four large baskets arranged around an axle. The force of the river's current rotated the baskets as with a conventional waterwheel, and salmon resting in the current would be caught in the basket. The basket would spill its contents as it came over the top of the wheel, and the fish would drop into a large pen or container. Fishwheels are still in use in some locations, particularly the Copper and Chilkat Rivers. They have the particular advantage of working without constant attendance, and harvesters can come by a few times a day to remove the caught fish and process them. Their disadvantage is that they are slow, and depend largely on luck to catch salmon being pushed downstream by the current; placement in well known channels increases the recovery, but still does not compare to more active means of harvest.

It should be noted that none of the traditional means of trapping salmon had a severe impact on the salmon population, and once enough fish were harvested in a certain area the people would move on to other locations, leaving the remaining run to spawn and guarantee future harvests. This is in contrast to the commercial fish traps used in Alaska in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries which devastated runs and in some cases completely destroyed spawning populations in some rivers.

In modern times with the advent of gasoline motors, winter trolling has become a common practice which provides fresh fish for the table in the coldest months which traditionally required dependence on stored fish. Trolling poles are similar to those used for sport fishing, but are much heavier and stronger with correspondingly heavier tackle and longer lines. They are set in the stern and along the side gunwales of a boat, baited or strung with flashing spoons or spinners. The boat then slowly motors around areas where salmon, usually kings, are known to school during the winter, aided by ultrasonic fish-finders. Periodically the lines are checked and brought in to remove fish. The same techniques are used for halibut as well. The harvest by this method is fairly small as it depends more on luck; salmon are not guaranteed to bite at lures and bait, unlike the certainty in catching them while spawning. Because of this limited take, trolling is usually avoided during spawning season and only used to bring home fresh fish in the winter. Trolling is often a family event done on the weekends, and often includes overnights on board. Because of the relative inactivity in trolling, the poles are not always well minded. This occasionally results in seals or whales snatching hooked fish still on the line and making off with them, causing much consternation and fun stories to tell later.

Salmon are roasted fresh over a fire, frozen, or dried and smoked for preservation. All species of salmon are harvested, and the Tlingit language clearly differentiates them. Certain species are considered to be more suited for a particular use, such as for hard smoking, canning, or baking. The most common storage methods today are vacuum-sealed freezing of raw fish, and either hard or soft smoking, the latter often followed by canning. Canning may be professionally done at local canneries or at home in mason jars. Smoking itself is done over alder wood either in small modern smoke houses near the family's dwelling or in larger ones at the harvesting sites maintained by particular families. For the former the fish are kept on ice after harvest and until they are brought home, however for the latter the processing is all performed on site.

The traditional methods of harvesting and processing salmon are still practiced to some extent, although often alongside more modern methods which require less effort. Salmon are cleaned as soon as they are harvested from the stream or river, and split along the back and left to hang dry on large racks for a few days. This is done to allow the fish's slime to evaporate and to make the flesh easier to work. Some claim that it is best to let the salmon soak in salt water overnight before drying, to further reduce the slime and soften the flesh. The drying racks must be watched continuously due to the threat of bears and birds poaching. Once dry the fish are further cut apart from head to tail and belly to back, then placed in a smokehouse for some period of time. The fish are at some point taken down and the fillets further split and slashed or crosshatched to allow more surface area for smoking. Once fully cured the fish are cut into strips and are ready to eat or store. Traditionally they were stored in bentwood boxes filled with seal oil. The oil protected the fish from mold and bacteria, and provided a secure method of long term storage for not only fish, but most other foodstuffs as well. Although once it was possible for people to identify the preparer of a given sample of smoked salmon by the knife patterns made in it, this practice is dying out and specific cutting patterns are dispensed with in favor of the simplest slashing or crosshatching.

During the summer harvesting season most people would live within their smokehouses, transporting the walls and floors from their winter houses to their summer locations where the frame for the house stood. Besides living in smokehouses, other summer residences were little more than hovels built from blankets and bark set up near the smokehouse. In the years following the introduction of European trade, canvas tents with woodstoves came into fashion. Since this was merely a temporary location, and since the primary purpose of the residence was not for living but for smoking fish, the Tlingit cared little for the summer house's habitability, as noted by early European explorers, and in stark contrast to the remarkable cleanliness maintained in winter houses.

Many Tlingit are involved in the Alaskan commercial salmon fisheries. Alaskan law provides for commercial fishermen to set aside a portion of their commercial salmon catch for subsistence or personal use, and today many families no longer fish extensively but depend on a few relatives in the commercial fishery to provide the bulk of their salmon store. Despite this, subsistence fishing is still widely practiced, particularly during weekend family outings.

Herring (Clupea pallasii) and hooligan (Thaleichthys pacificus) both provide important foods in the Tlingit diet. They are small fish which return in enormous schools to spawn near the mouths of freshwater rivers and streams. Herring are traditionally harvested with herring rakes, long poles with spikes which are swirled around in the schooling fish. An experienced herring raker can bring up ten or more fish with each swing, and deftly flick the fish from the rake into the bottom of the boat. Raking can be enhanced with pens, weirs, and other techniques of condensing the large schools. More modern methods usually involve small aperture nets and purse seining. Herring are usually processed like salmon, dried and smoked whole. Cleaning and removal of the viscera is optional, and if being frozen whole many do not bother due to the diminutive size of the fish. They are traditionally stored by submerging in seal oil (the "Tlingit refrigerator"), but in modern times may be canned, salted, or frozen, the latter usually in vacuum sealed bags.

Herring eggs are also harvested, and are considered a delicacy, sometimes called "Tlingit caviar." Either ribbon kelp or (preferably) hemlock branches are submerged in an area where herring are known to spawn, and are marked with a buoy. They may be unattended during spawning, or the herring may be herded into the area and penned with nets to force them to spawn on the kelp or hemlock. Once enough eggs are deposited the herring are released from the pen to spawn further, thus ensuring future harvests. The branches or kelp are removed and boiled in large cauldrons or fifty-five gallon drums on the beach, often as part of a family or community event. Children are often tasked with stirring the water with large paddles, and this provides many fond memories for adults. The cooked eggs may be salted, frozen, dried in cakes, or submerged in seal oil to preserve them for use throughout the year. Bringing herring eggs to a gathering always results in oohs and aahs as people sample them, and frequently induces an elder to relate herring stories. Some Tlingit are connoisseurs, knowing certain regions by their flavor or texture, and good harvest grounds are often jealously guarded secrets.

Hooligan are harvested by similar means as herring, however they are valued more for their oil than for their flesh. Instead of smoking, they are usually tried for their oil by boiling and mashing in large cauldrons or drums (traditionally old canoes and hot rocks were used), the oil skimmed off the surface with spoons and then strained and stored in bentwood boxes (today in commercial containers, eg glass jars). Hooligan oil was a valuable trade commodity which enriched khwáan such as the Chilkat who saw regular hooligan runs every year in their territory. Today hooligan are, when not tried for their oil, most often vacuum sealed and frozen, kept in the large freezers found outside many Tlingit households.

When cooked, both herring and hooligan are usually served whole with heads still attached. Some people eat the entire fish, others strip the meat and viscera off with their teeth and leave the skeleton; eating of the viscera is very common, in contrast with the universal disposal of salmon viscera. Methods of preparation often involve deep-frying or pan frying, although baking is also common and is more traditional. As with salmon, they may be pierced with a stick and set over a fire to roast; this is a particularly common practice during the harvest when overnighting at a remote location, or at a beach party or picnic.

Unlike almost all other north Pacific coast peoples, the Tlingit do not hunt whale. Various explanations have been offered, but the most common reason given is that since a significant portion of the society relates itself with either the killer whale or other whale species via clan crest and hence as a spiritual member of the family, eating whale would be tantamount to cannibalism. A more practical explanation follows from the tendency of the Tlingit to harvest and eat in moderation despite the surrounding abundance of foodstuffs. Thus whale is treated similarly to shellfish, as a second class food which should only be eaten when other sources of food have failed, and whose consumption indicates poverty. Since a whale provides a large amount of food which easily spoils, and distribution of food outside the household would require elaborate and expensive potlatching. Whale hunting is also a large cooperative endeavor and would require extensive interaction between clans for success; such interactions would then produce obligations which would be difficult to repay. Thus the Tlingit have avoided the whale harvest for sociopolitical and socioeconomic reasons.

The Gulf Coast Tlingit around Yakutat are the exception to the rule, hunting whale occasionally. Many Tlingit explain the Gulf Coast whale hunt as an areal influence of the Eyak and the Alutiiq Eskimos of Prince William Sound further north. However, all Tlingit eat beached whales, considering this a gift that should not be wasted. A story in the Raven Cycle relates how Raven was swallowed by a whale and then ate it from inside out, eventually killing and beaching it; this is considered to justify Tlingit harvests of beached whales. However, beached whales are fairly uncommon in Southeast Alaska since the beaches are very rocky and often nearly nonexistent, thus whale forms only a very small part of the Tlingit diet.

Game forms a sizable component of the traditional Tlingit diet, and the majority of food that is not derived from the sea. Major game animals hunted for food are Sitka deer, rabbit, mountain goat in mountainous regions, black bear and brown bear, beaver, and, on the mainland, moose.

Religion

Tlingit thought and belief, although never formally codified, was historically a fairly well organized philosophical and religious system whose basic axioms shaped the way all Tlingit people viewed and interacted with the world around them. Between 1886-1895, in the face of their shamans' inability to treat Old World diseases including smallpox, most of the Tlingit people converted to Orthodox Christianity. (Russian Orthodox missionaries had translated their liturgy into the Tlingit language.) After the introduction of Christianity, the Tlingit belief system began to erode.

Today, some young Tlingits look back towards what their ancestors believed, for inspiration, security, and a sense of identity. This causes some friction in Tlingit society, because most modern Tlingit elders are fervent believers in Christianity, and have transferred or equated many Tlingit concepts with Christian ones. Indeed, many elders believe that resurrection of heathen practices of shamanism and spirituality are dangerous, and are better forgotten.

The philosophy and religion of the Tlingit, although never formally codified, was historically a fairly well organized philosophical and religious system whose basic axioms shaped the way all Tlingit people viewed and interacted with the world around them. Between 1886-1895, in the face of their shamans' inability to treat Old World diseases including smallpox, most of the Tlingit people converted to Orthodox Christianity. (Russian Orthodox missionaries had translated their liturgy into the Tlingit language.) After the introduction of Christianity, the Tlingit belief system began to erode.

Today, some young Tlingits look back towards what their ancestors believed, for inspiration, security, and a sense of identity. This causes some friction in Tlingit society, because most modern Tlingit elders are fervent believers in Christianity, and have transferred or equated many Tlingit concepts with Christian ones. Indeed, many elders believe that resurrection of heathen practices of shamanism and spirituality are dangerous, and are better forgotten.

Dualism

The Tlingit see the world as a system of dichotomies. The most obvious is the division between the light water and the dark forest which surrounds their daily lives in the Tlingit homeland.

Water serves as a primary means of transportation, and as a source of most Tlingit foods. Its surface is flat and broad, and most dangers on the water are readily perceived by the naked eye. Light reflects brightly off the sea, and it is one of the first things that a person in Southeast Alaska sees when they look outside. Like all things, danger lurks beneath its surface, but these dangers are for the most part easily avoided with some caution and planning. For such reasons it is considered a relatively safe and reliable place, and thus represents the apparent forces of the Tlingit world.

In contrast, the dense and forbidding rainforest of Southeast Alaska is dark and misty in even the brightest summer weather. Untold dangers from bears, falling trees, dank muskeg, and the risk of being lost all make the forest a constantly dangerous place. Vision in the forest is poor, reliable landmarks are few, and food is scarce in comparison to the seashore. Entering the forest always means travelling uphill, often up the sides of steep mountains, and clear trails are rare to nonexistent. Thus the forest represents the hidden forces in the Tlingit world.

Another series of dichotomies in Tlingit thought are wet versus dry, heat versus cold, and hard versus soft. A wet, cold climate causes people to seek warm, dry shelter. The traditional Tlingit house, with its solid redcedar construction and blazing central fireplace, represented an ideal Tlingit conception of warmth, hardness, and dryness. Contrast the soggy forest floor that is covered with soft rotten trees and moist, squishy moss, both of which make for uncomfortable habitation. Three attributes that Tlingits value in a person are hardness, dryness, and heat. These can be perceived in many different ways, such as the hardness of strong bones or the hardness of a firm will; the heat given off by a healthy living man, or the heat of a passionate feeling; the dryness of clean skin and hair, or the sharp dry scent of cedar.

Spirituality

The Tlingit divide the living being into several components:

- khaa daa—body, physical being, person's outside (cf. aas daayí "tree's bark or outside")

- khaa daadleeyí—the flesh of the body (< daa + dleey "meat, flesh")

- khaa ch'áatwu—skin

- khaa s'aaghí—bones

- xh'aséikw—vital force, breath (< disaa "to breathe")

- khaa toowú—mind, thought and feelings

- khaa yahaayí—soul, shadow

- khaa yakghwahéiyagu—ghost, revenant

- s'igheekháawu—ghost in a cemetery

The physical components are those that have no proper life after death. The skin is viewed as the covering around the insides of the body, which are divided roughly into bones and flesh. The flesh decays quickly, and in most cases has little spiritual value, but the bones form an essential part of the Tlingit spiritual belief system. Bones are the hard and dry remains of something which has died, and thus are the physical reminder of that being after its death. In the case of animals, it is essential that the bones be properly handled and disposed, since mishandling may displease the spirit of the animal and may prevent it from being reincarnated. The reason for the spirit's displeasure is rather obvious, since a salmon who was resurrected without a jaw or tail would certainly refuse to run again in the stream where it had died.

The significant bones in a human body are the backbone and the eight "long bones" of the limbs. The eight long bones are emphasized because that number has spiritual significance in Tlingit culture. The bones of a cremated body must be collected and placed with those of the person's clan ancestors, or else the person's spirit might be disadvantaged or displeased in the afterlife, which could cause repercussions if the ghost decided to haunt people or if the person was reincarnated.

The source of living can be found in xh'aséikw, the essence of life. This bears some resemblance to the Chinese concept of qi as a metaphysical energy without which a thing is not alive; however in Tlingit thought this can be equated to the breath as well. For example, the shaman's simplest test for whether a person is alive is to hold a downy feather above the mouth or nose; if the feather is disturbed then the person is breathing and thus alive, even if the breath is not audible or sensible. This then implies that the person still maintains xh'aséikw.

The feelings and thoughts of a person are encompassed by the khaa toowú. This is a very basic idea in Tlingit culture. When a Tlingit references their mind or feelings, he always discusses this in terms of axh toowú, "my mind." Thus "Axh toowú yanéekw," "I am sad," literally "My mind is pained."

Both xh'aséikw and khaa toowú are mortal, and cease to exist upon the death of a being. However, the khaa yahaayí and khaa yakghwahéiyagu are immortal and persist in various forms after death. The idea of khaa yahaayí is that it is the person's essence, shadow, or reflection. It can even refer to the appearance of a person in a photograph or painting, and is metaphorically used to refer to the behavior or appearance of a person as other than what he is or should be.

Creation story and the Raven Cycle

Stories about Raven are unique in Tlingit culture in that though they technically belong to clans of the Raven moiety, most are openly and freely shared by any Tlingit no matter their clan affiliation. They also make up the bulk of the stories that children are regaled with when young. Raven Cycle stories are often shared anecdotally, the telling of one inspiring the telling of another. Many are humorous, but there are some which are very serious and impart a sense of Tlingit morality and ethics, and others which belong to specific clans and may only be shared under appropriate license. Some of the most popular are those which are known to other tribes along the Northwest Coast, and which provide the creation myths for the everyday world.

There are two different Raven characters which can be identified in the Raven Cycle stories, although they are not always clearly differentiated by most storytellers. One is the creator Raven who is responsible for bringing the world into being and who in sometimes considered to be the same individual as the Owner of Daylight. The other is the childish Raven, always selfish, sly, conniving, and hungry. Comparing a few of the stories reveals logical inconsistencies between them, however this is usually explained as involving a different world where things did not make logical sense, a mythic time when the rules of the modern world did not apply.

The theft of daylight

The most well recognized story of is that of the Theft of Daylight, in which Raven steals the stars, the moon, and the sun from Naas-sháki Yéil or Naas-sháki Shaan, the Raven (or Old Man) at the Head of the Nass River. The Old Man is very rich and is the owner of three legendary boxes which contain the stars, the moon, and the sun; Raven wants these for himself (various reasons are given, such as wanting to admire himself in the light, wanting light to find food easily, etc). Raven transforms himself into a hemlock needle and drops into the water cup of the Old Man's daughter while she is out picking berries. She becomes pregnant with him and gives birth to him as a baby boy. The Old Man dotes over his grandson, as is the wont of most Tlingit grandparents. Raven cries incessantly until the Old Man gives him the Box of Stars to pacify him. Raven plays with it for a while, then opens the lid and lets the stars escape through the chimney into the sky. Later Raven begins to cry for the Box of the Moon, and after much fuss the Old Man gives it to him but not before stopping up the chimney. Raven plays with it for a while and then rolls it out the door, where it escapes into the sky. Finally Raven begins crying for the Box of the Sun, and after much fuss finally the Old Man breaks down and gives it to him. Raven knows well that he cannot roll it out the door or toss it up the chimney because he is carefully watched. So he finally waits until everyone is asleep and then changes into his bird form, grasps the sun in his beak and flies up and out the chimney. He takes it to show others who do not believe that he has the sun, so he opens the box to show them and then it flies up into the sky where it has been ever since.

Death and the afterlife

Heat, dryness, and hardness are all represented as parts of the Tlingit practice of cremation. The body is burned, removing all water under great heat, and leaving behind only the hard bones. The soul goes on to be near the heat of the great bonfire in the house in the spirit world, unless it is not cremated in which case it is relegated to a place near the door with the cold winds. The hardest part of the spirit, the most physical part, is reincarnated into a clan descendant.

Shamanism

The shaman is called ixht'. He was the healer, and the one who foretold the future. He was called upon to heal the sick, drive out those who practiced witchcraft, and tell the future.

It is a mis-nomer to call him "witch doctor" as the practices of the ixht' and the "witch" are completely different and they were at odds with each other. To call one a medicine man is not correct either as "medicine master" is naak'w s'aati, which is the Tlingit term for a witch.

The name of the ixt' and his songs and stories of his visions are the property of the clan he belongs to. He would seek spirit helpers from various animals and after fasting for four days when the animal would 'stand up in front of him' before entering him he would obtain the spirit. The tongue of the animal would be cut out and added to his collection of spirit helpers. This is why he was referred to by some as "the spirit man."

A nephew of a shaman could inherit his position. He would be told how to approach the grave and how to handle the objects. Touching shaman objects was strictly forbidden except to a shaman and his helpers.

All shamans are gone from the Tlingit today and their practices will likely never be revived, although shaman spirit songs are still done in their ceremonies, and their stories re-told at those times.

Kooshda

The Kooshdakhaa (kû'cta-qa) are the dreaded and feared Land Otter People, human from the waist up, and otter-like below. Land otters are excellent fishers. Those who are drowned often marry (and become) land otters, and land otters can assist in drownings. Land otters are sinister and potentially harmful. When properly controlled, however, the land otter can be of great help to humans, such as fishermen who penetrate the sacred realm beyond social boundaries. Those drowned and married to land otters (and their land otter children) can return to their human relations and assist them, usually by helping them catch abundant supplies of seafood. The land otters can make human children grow tails; they can only eat raw food, for if they eat cooked fish they will die; and as supernatural beings, after being out on the water they must regain land and find shelter before the raven calls or they will die.

History

The history of the Tlingit involves both pre-contact and post-contact historical events and stories. The traditional history involved the creation stories, the Raven Cycle, other tangentially related events during the mythic age when spirits freely transformed from animal to human and back, the migration story of coming to Tlingit lands, the clan histories, and more recent events near the time of first contact with Europeans. At this point the European and American historical records come into play, and although modern Tlingits have access to and review these historical records, they continue to maintain their own historical record by telling stories of ancestors and events which have importance to them against the background of the changing world.

The Tlingit migration

There are a few variations of the Tlingit story of how they came to inhabit their lands. All are fairly similar, and one will be detailed here. They vary mostly in location of the events, with some being very specific about particular rivers and glaciers, others being more vague. The particular one presented here involves some interesting relationship explanations between the Tlingit and their inland neighbors, the Athabaskans. Note that the particular Athabaskan group is not noted, and it seems to be indeterminate. It may in fact refer to a time before the Athabaskans had developed into the multiplicity of peoples that they are today.

All stories are considered property in the Tlingit cultural system, such that sharing a story without the proper permission of its owners is a breach of Tlingit law. However, the stories of the Tlingit people as a whole, the creation myths, and other seemingly universal records are usually considered to be property of the entire tribe, and thus may be shared without particular restriction. It is however important to the Tlingit that the details be correct, for if not this can lead to perpetuations of error and worsen the transmission of the information in the future, as well as degrade the value of the knowledge.

The story begins with the Athabaskan (Ghunanaa) people of interior Alaska and western Canada, a land of lakes and rivers, of birch and spruce forests, and the moose and caribou. Life in this continental climate is harsh, with bitterly cold winters and hot summers. One year the people had a particularly poor harvest over a summer, and it was obvious that the winter would bring with it many deaths from starvation. The elders gathered together and decided that people would be sent out to find a land which was rumored to be rich in food, a place where one did not even have to hunt for something to eat. A group of people were selected and sent out to find this new place, and would come back to tell the elders where this land could be found. They were never heard from again. However, we now know that these people were the Navajo and Apache, for they left the Athabaskan lands for a different place far south of their home, and yet retain a close relationship with their Athabaskan ancestors.

Over the winter countless people died. Again, the next summer's harvest was poor, and the life of the people was threatened. So once again, the elders decided to send out people to find this land of abundance. These people travelled a long distance, and climbed up mountain passes to encounter a great glacier. The glacier seemed impassable, and the mountains around it far too steep for the people to cross. They could however see how the meltwater of the glacier traveled down into deep crevasses and disappeared underneath the icy bulk. The people decided that some strong young men should be sent down to follow this river to see if it came out on the other side of the mountains. But before these men had left, an elderly couple volunteered to make the trip. They reasoned that since they were already near the end of their lives, the loss of their support to the group would be minimal, but the loss of the strong young men would be devastating. The people agreed that these elders should travel under the glacier. They made a simple dugout canoe and took it down the river under the glacier, and came out to see a rocky plain with deep forests and rich beaches all around. The people followed them down under the glacier and came into Lingít Aaní, the rich and bountiful land that became the home of the Tlingit people. These people became the first Tlingits.

Another theory of Tlingit migration is that of the Beringia Land Bridge. Coastal people in general are extremely aggressive; whereas interior Athapascan people are passive. Tlingit culture, being the fiercest among the coastal nations due to their northernmost occupation, began to dominate the interior culture as they traveled inland to secure trading alliances. Tlingit traders were the "middlemen" bringing Russian goods inland over the Chilkoot Trail to the Yukon, and on into Northern British Columbia. As the Tlingit people began marrying interior people, their culture became the established "norm." Soon the Tlingit clan and political structure, as well as customs and beliefs dominated all other interior culture. To this day, Tlingit regalia, language, clan structure, political structure, and ceremonies including beliefs are evident in all interior culture. The Athapascan way of life is now embedded with the Tlingit people's lifestyle.

Clan histories

The clans were Yehi, or Raven; Goch, or Wolf; and Nehadi, or Eagle.

Each clan in Tlingit society has its own foundation history. These stories are private property of the clan in question and thus may not be shared here. However, each story describes the Tlingit world from a different perspective, and taken together the clan histories recount much of the history of the Tlingits before the coming of the Dléit Khaa, the white people.

Typically a clan history involves some extraordinary event that happened to some family or group of families which brought them together and at once separated them from other Tlingits. Some clans seem to be older than others, and often this is notable by their clan histories having mostly mythic proportions. Younger clans seem to have histories that tell of breaking apart from other groups due to internal conflict and strife or the desire to find new territory. For example, the Deisheetaan are descended from the Ghaanaxh.ádi, but their clan foundation story tells little or nothing of this relationship. In contrast, the Khák'w.wedí who are descended from the Deisheetaan usually mention their connection as an aside in the telling of their foundation story. Presumably this is the case because their separation was more recent, and is thus well remembered, whereas the separation of the Deisheetaan from the Ghaanaxh.ádi is less apparent in the minds of the Deisheetaan clan members.

First contact

A number of both well-known and indistinguished European explorers investigated Lingít Aaní and encountered the Tlingit in the earliest days of contact. Most of these exchanges were congenial, despite European fears to the contrary. The Tlingit rather quickly appreciated the trading potential for valuable European goods and resources, and exploited this whenever possible in their early contacts. On the whole the European explorers were impressed with Tlingit wealth, but put off by what they felt was an excessive lack of hygiene. Considering that most of the explorers visited during the busy summer months when Tlingit lived in temporary camps, this impression is unsurprising. In contrast, the few explorers who were forced to spend time with the Tlingit Tribe during the inclement winters made mention of the cleanliness of Tlingit winter homes and villages.

- Bering and Chirikov (1741)

Vitus Bering was separated from Aleksei Chirikov and only reached as far east as Kayak Island. However Chirikov traveled to the western shores of the Alexander Archipelago. He lost two boats of men around Lisianski Strait at the northern end of Chichagof Island. Subsequently Chirikov encountered Tlingit whom he felt were hostile, and returned west.

- First Bucareli Expedition (1774)

Juan Josef Pérez Hernández sent by Don Antonio María de Bucareli y Ursúa, Viceroy of New Spain, to explore to north 60 latitude in 1774. Accompanied by Fray Juan Crespi and Fr. Tomás de la Peña Suria (or Savaria). Suria executed a number of drawings which today serve as invaluable records of Tlingit life in the precolonial period.

- Second Bucareli Expedition (1775)

Lt. Bruno de Hezeta (or Heceta) commanded the expedition aboard the Santiago, with Lt. Juan Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra leading the Sonora as second in command. Hezeta returned to Mexico shortly after a massacre by the Quinault near the Quinault River in modern Washington, but Bodega y Quadra insisted upon completing the mission to reach 60º north latitude. He traveled almost as far as Sitka, Alaska to 59º north, claimed possession of the lands he encountered for Spain, and named Mt. Edgecumbe as "Mount Jacinto." It is unclear whether the expedition ever encountered the Tlingit.

- James Cook (1778)

James Cook acquired possession of the journals of Bodega y Quadra's second commander Francisco Mourelle and of maps created from the two previous Bucareli Expeditions. This inspired him to investigate the northwest coast of America on his third voyage, in search of the Northwest Passage.

- Third Bucareli Expedition (1779)

Lt. Ignacia de Arteaga officially led this expedition in the Princesa, however Bodega y Quadra was the more experienced explorer and accompanied the expedition aboard the Favorita. They made contact and traded with the Tlingits around Bucareli Bay (Puerto de Bucareli). They also named Mount Saint Elias.

- Potap Zaikov

- La Pérouse (1786)

Jean-François de Galaup, comte de La Pérouse

- George Dixon (1787)

George Dixon (captain)

- James Colnett (1788)

James Colnett

- Ismailov and Bocharov (1788)

Gerasim Izmailov and Dmitry Bocharov

- William Douglas (1788)

- Alessandro Malaspina (1791)

Alessandro Malaspina, after whom the Malaspina Glacier is named, explored the Alaskan coast as far north as Prince William Sound. His expedition made contact with the Laxhaayík Khwáan of the Yakutat area upon reaching Yakutat Bay.

- George Vancouver (1794)

George Vancouver

Fur trade

The Battle of Sitka (1804) was the last major armed conflict between Europeans and Alaska Natives, and was initiated in response to the destruction of a Russian trading post two years prior. The primary combatant groups were the native Tlingits of Sheet’-ká X'áat'l (Baranof Island) and agents of the Russian-American Company. Though the Russians' initial assault (in which Alexandr Baranov, head of the Russian expedition, sustained serious injuries) was repelled, their naval escorts bombarded the Tlingit fort Shis'kí Noow mercilessly, driving the natives into the surrounding forest after only a few days. The Russian victory was decisive, and resulted in the Tlingit being permanently displaced from their ancestral lands. The Tlingit fled north and established a new settlement on the neighboring Chichagof Island.

Animosity between the two cultures, though greatly diminished, continued in the form of sporadic attacks by the natives against the Russian settlement as late as 1858. The battlefield location has been preserved at Sitka National Historical Park.

U.S. President Benjamin Harrison set aside the Shis'kí Noow site for public use in 1890. Sitka National Historical Park was established on the battle site on October 18, 1972 "...to commemorate the Tlingit and Russian experiences in Alaska." Today, the K'alyaan (Totem) Pole stands guard over the Shis'kí Noow site to honor the Tlingit casualties. Ta Éetl, a memorial to the Russian sailors who died in the Battle, is located across the Indian River at site of the Russians' landing. In September of 2004, in observance of the Battle's bicentennial, descendants of the combatants from both sides joined in a traditional Tlingit "Cry Ceremony" to formally grieve their lost ancestors. The next day, the Kiks.ádi hosted a formal reconciliation ceremony to "put away" their two centuries of grief.

The bombing of Angoon

At a rendering plant located near Angoon in October 1882, a shaman and aristocrat by the name of Til'tlein was killed in an accident involving the factory's boats and harpoon bombs. Another man had been violently killed recently, and his relatives had not been compensated by the factory managers for his death, a customary Tlingit practice which they had engaged previously. The Tlingits had let the matter rest since they were interested in maintaining friendly relations, but when Til'tlein was killed and the owners again refused to compensate, the Angoon residents followed traditional Tlingit practice and seized the boats and weapons involved in the death and took a few whites hostage until such time as the factory managers repaid them for the deaths. They claimed compensation of two hundred blankets from the factory.

Incensed at the theft and perhaps misunderstanding the situation as a threat, the owners sent word to the US Naval Commander Merriman in Sitka. Merriman came to Angoon aboard the revenue cutter Corwin and demanded that the Angoon people return the boats and men and pay a fine of four hundred blankets in twenty-four hours or suffer bombing from the cutter's cannons. The following morning only 80 blankets were produced and Merriman proceeded to destroy the canoes on the beach, shell the houses and storehouses, and send a landing party in to loot and burn the remaining town.

The looting and burning of the storehouses destroyed most of the Angoon people's possessions and food which they had put up for winter, and that year many people died of starvation. It took five years for the town to be rebuilt to the size at which it was before the bombing. This incident, concomitant with the gold rush in Juneau forced the US government into recognizing the need for a formal Territorial Government to replace the extant martial law which had been in place since the Alaska Purchase.

The residents of Angoon have long held out for a formal apology for what they consider was undue terrorizing punishment for a cultural misunderstanding. In 1973 the US government offered a ninety thousand dollar settlement to the village of Angoon in response to the bombardment, but the government and the US Navy declined to offer a formal apology. In 1982 on the centennial anniversary of the bombing a memorial potlatch was held, attended by Tlingit dignitaries from all across Southeast Alaska and by then Governor Jay Hammond in which the people of Angoon formally made public their feelings and opinions on the matter, and demanded an apology from the US Navy. No representatives of the Navy attended despite a formal invitation, and no apology has been forthcoming despite repeated requests from the town government, the Tlingit tribal organizations, and representatives of the State of Alaska.

20th Century Trivia

Two Tlingit brothers initially created the Alaska Native Brotherhood in 1912 in Sitka in order to pursue the privileges of whites in the area at the time. The Alaska Native Sisterhood followed. ANB and ANS now function as nonprofit organizations serving to assist in societal development and the preservation of Native culture, and ensure all people are treated equally. Aleuts were forcibly encamped by the United States government throughout Southeast Alaska during World War II. Elizabeth Peratrovich was a renowned member of the ANS for whom in 1988 the State of Alaska designated a state holiday, of February 16. Tlingits were an important driving force behind passage of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of December 18, 1971.

Prominent Tlingits

- Diane E. Benson, politician

- Nora Marks Dauenhauer, writer and scholar

- George Hunt, ethnologist (adopted into Kwakwaka'wakw)

- William Paul, Native rights activist

- Elizabeth Peratrovich, political activist

- Louis Shotridge, ethnologist

Anthropologists and other scholars who have worked among the Tlingit

- Nora Marks Dauenhauer

- Richard Dauenhauer

- George T. Emmons

- Viola Garfield

- Frederica de Laguna

- Kirk Dombrowski

- Sergei Kan

- Edward L. Keithahn

- Aurel Krause

- Steve J. Langdon

- Jeff Leer

- Catherine McClellan

- Madonna Moss

- Kalervo Oberg

- Ronald Olson

- Louis Shotridge

- Ian Stevenson

- John R. Swanton

- Thomas F. Thornton

Notes

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ames, Kenneth M. & Maschner, Herbert D.G. (1999). Peoples of the Northwest Coast: Their archaeology and prehistory. London: Thames and Hudson, Ltd. ISBN 0-500-28110-6.

- Bullen, Edward L. (1968). An historical study of the education of the Indians of Teslin, Yukon Territory. (Unpublished master's thesis, University of Alberta, Edmonton).

- Emmons, George Thornton (1991). The Tlingit Indians. Volume 70 in Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History. Edited with additions by Frederica De Laguna. New York: American Museum of Natural History. ISBN 0-295-97008-1.

- Dauenhauer, Nora Marks & Dauenhauer, Richard (1987). Haa Shuká, Our Ancestors: Tlingit oral narratives. Volume 1 in Classics of Tlingit Oral Literature. Seattle, Washington: University of Washington Press. ISBN 0-295-96495-2.

- ———(1990). Haa Tuwunáagu Yís, for Healing our Spirit: Tlingit oratory. Volume 2 in Classics of Tlingit Oral Literature. Seattle, Washington: University of Washington Press. ISBN 0-295-96850-8.

- ———(1994). Haa Kusteeyí, Our Culture: Tlingit life stories. Volume 3 in Classics of Tlingit Oral Literature. Seattle, Washington: University of Washington Press. ISBN 0-295-97401-X.

- De Laguna, Frederica (1960). The Story of a Tlingit Community. Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology: bulletin 172. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office.

- ———(1972). Under Mount Saint Elias: The history and culture of the Yakutat Tlingit. Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology: volume 7 (in three parts). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office.

- ———(1990). Tlingit. In W. Suttles (Ed.), Northwest Coast (pp. 203-228). Handbook of North American Indians (Vol. 7) (W. C. Sturtevant, General Ed.). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

- Dombrowski, Kirk (2001) Against Culture: Development, Politics and Religion in Indian Alaska. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- Eliade, Mircea (1964). Shamanism: Archaic techniques of ecstasy. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-01779-4.

- French, Diana E. (1974). Taku recovery project: A preliminary report for the Atlin band. Archaeology Sites Advisory Board permit no. 29-73. (Unpublished).

- Garfield, Viola E. (1947). "Historical aspects of Tlingit clans in Angoon, Alaska." American Anthropologist 49:438–453.

- Garfield, Viola E. & Forrest, Linn A. (1961). The Wolf and the Raven: Totem poles of Southeast Alaska. Seattle, Washington: University of Washington Press. ISBN 0-295-73998-3.

- Goldschmidt, Walter R. and Haas, Theodore H. (1998). Haa Aaní, Our Land. Seattle, Washington: University of Washington Press. ISBN 0-295-97639-X.

- Holm, Bill (1965). Northwest Coast Indian Art: An analysis of form. Seattle, Washington: University of Washington Press. ISBN 0-295-95102-8

- Hope III, Andrew (1982). Raven's Bones. Sitka, Alaska: Sitka Community Association. ISBN 0-911417-00-1.

- ———(2000). Will the Time Ever Come? : A Tlingit sourcebook. Fairbanks, Alaska: Alaska Native Knowledge Network. ISBN 1-877962-34-1.

- Huteson, Pamela Rae (2002). Legends in Wood, Stories of the Totems. Portland, Oregon: Greatland Classic Sales. ISBN 1-886462-51-8

- Kaiper, Nan (1978). Tlingit: Their art, culture, and legends. Vancouver, British Columbia: Hancock House Publishers, Ltd. ISBN 0-88839-010-6.

- Kamenskii, Fr. Anatolii (1985). Tlingit Indians of Alaska. Translated with additions by Sergei Kan. Volume II in Marvin W. Falk (Ed.), The Rasmuson Library Historical Translations Series. Fairbanks, Alaska: University of Alaska Press. Originally published as Indiane Aliaski, Odessa, 1906. ISBN 0-912006-18-8.

- Kan, Sergei (1989). Symbolic Immortality: The Tlingit potlatch of the nineteenth century. William L. Merrill and Ivan Karp (Eds.), Smithsonian Series in Ethnographic Inquiry. ISBN 1-56098-309-4.

- Krause, Arel (1956). The Tlingit Indians. Translated by Erna Gunther. Seattle, Washington: University of Washington Press. Originally published as Die Tlinkit-Indianer, Jena, 1885. ISBN 0-295-95075-7.

- McClellan, Catharine (1950). Culture change and native trade in southern Yukon territory. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of California, Berkeley).

- ———(1953). The inland Tlingit. In M. W. Smith (Ed.), Asia and North America: Transpacific contacts (pp. 47-51). Memoirs of the Society for American Archaeology (No. 9). Salt Lake City: Society for American Archaeology. (Reprinted 1974, 1979).

- ———(1954). The interrelations of social structure with northern Tlingit ceremonialism. Southwestern Journal of Anthropology, 10 (1), 75-96.

- ———(1970). Indian stories about the first whites in northwestern America. In M. Lantis (Ed.), Ethnohistory in southwestern Alaska and the southern Yukon: Method and content (pp. 103-133). Studies in anthropology (No. 7). Lexington: University Press of Kentucky.

- ———(1975). My old people say: An ethnographic survey of southern Yukon territory. [2 books]. Publications in Ethnology (No. 6). Ottawa: National Museum of Man (National Museums of Canada).

- ———(1981). Inland Tlingit. In J. Helm (Ed.), Subarctic (pp. 469-480). Handbook of Native American Indians (Vol. 6) (W. C. Sturtevant, Gen. Ed.). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

- McClellan, Catharine; & Rainier, Dorothy. (1950). Ethnological survey of southern Yukon territory, 1948. (Preliminary report). National Museum of Canada Bulletin, 118, 50-53.

- Moss, Madonna Lee (1989). Archaeology and cultural ecology of the prehistoric Angoon Tlingit. Doctoral dissertation, University of California, Santa Barbara.

- Peratrovich, Robert J. Jr. (1959). Social and economic structure of the Henya Indians. Masters dissertation, University of Alaska, Fairbanks.

- Salisbury, O.M. (1962). The customs and legends of the Thlinget Indians of Alaska. New York: Bonanza Books. ISBN 0-517-13550-7.

- Swanton, John R. (1909). Tlingit myths and texts. Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology: bulletin 39. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Teslin Women's Institute (1972). A history of the settlement of Teslin. Teslin, Yukon.

External links