Difference between revisions of "Three Kingdoms of Korea" - New World Encyclopedia

Dan Davies (talk | contribs) (New page: {{koreanname| image=200px|Map of the Three Kingdoms of Korea, at the end of the 5th century| hangul=삼국시대|hanja=三國時代|rr=Samguk Sida...) |

Dan Davies (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | {{claimed}} | ||

{{koreanname| | {{koreanname| | ||

image=[[Image:Three Kingdoms of Korea Map.png|200px|Map of the Three Kingdoms of Korea, at the end of the 5th century]]| | image=[[Image:Three Kingdoms of Korea Map.png|200px|Map of the Three Kingdoms of Korea, at the end of the 5th century]]| | ||

Revision as of 20:22, 24 April 2007

| Three Kingdoms of Korea | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||

| Korean name | ||||||||

|

The Three Kingdoms Period of Korea (hangul: 삼국시대) featured the three rival kingdoms of Goguryeo, Baekje and Silla, which dominated the Korean peninsula and parts of Manchuria for much of the 1st millennium CE. The Three Kingdoms period in Korea is usually considered to run from the 1st century BCE (specifically 57 B.C.E.) until Silla's triumph over Goguryeo in 668, which marked the beginning of the North and South States period (남북국시대) of Unified Silla in the South and Balhae in the North.

The earlier part of this period, before the three states developed into full-fledged kingdoms, is sometimes called Proto-Three Kingdoms of Korea.

Background

The name "Three Kingdoms" was used in the Korean titles of the histories Samguk Sagi (12th century) and Samguk Yusa (13th century).

|

Jeulmun Period

|

The three city-states were founded soon after the fall of Gojoseon, and gradually conquered and absorbed various other small states and confederacies. After the fall of Gojoseon, the Han dynasty established four commanderies in northern parts of the Korean peninsula. Three fell quickly to the Samhan, and the last was destroyed by Goguryeo in 313.

Baekje and Silla expanded within the Samhan confederacies, and Goguryeo conquered neighboring Buyeo, Okjeo, Dongye, and other statelets in northern Korea and Manchuria. The three became full-fledged kingdoms by around 300 C.E., prior to which is sometimes called the Proto-Three Kingdoms period.

All three kingdoms shared a similar culture and language. Their original religions appear to have been shamanistic, but they were increasingly influenced by Chinese culture, particularly Confucianism and Taoism. In the 4th century, Buddhism was introduced to the peninsula and spread rapidly, briefly becoming the official religion of all three kingdoms.

Goguryeo

Goguryeo emerged on the north and south banks of the Yalu (Amrok) River, in the wake of Gojoseon's fall. The first mention of Goguryeo in Chinese records dates from 75 BCE in reference to a commandery established by the Chinese Han dynasty, although even earlier mentions of "Guri" may be of the same state. Evidence indicates Goguryeo was the most advanced, and likely the first established, of the three kingdoms.

Goguryeo, eventually the largest of the three kingdoms, had several capitals in alternation: two capitals in the upper Yalu area, and later Nak-rang (樂浪: Lelang in Chinese) which is now part of Pyongyang. At the beginning, the state was located on the border with China; it gradually expanded into Manchuria and destroyed the Chinese Lelang commandery in 313 CE. The cultural influence of the Chinese continued as Buddhism was adopted as the official religion in 372 CE.

The kingdom was at its zenith in the fifth century when occupying the Liaodong Plains in Manchuria and today's Seoul area. The Goguryeo kings controlled not only Koreans but also Chinese and other Tungusic tribes in Manchuria and North Korea. After the establishment of the Sui Dynasty in China, the kingdom continued to suffer from Chinese attacks until conquered by the allied Silla-Tang forces in 668 C.E. Goguryeo, was, in fact, the protector of the Korean peninsula. Without Goguryeo blocking out Chinese invaders, Silla and Baekche would surely have fallen.

Baekje

Baekje was founded as a member of the Mahan confederacy. Two sons of Goguryeo's founder are recorded to have fled a succession conflict, to establish Baekje around the present western Korean peninsula.

Baekje absorbed or conquered other Mahan chiefdoms and, at its peak in the 4th century, controlled most of the western Korean peninsula. Under attack from Goguryeo, the capital moved south to Ungjin (present-day Gongju) and later further south to Sabi (present-day Buyeo).

Baekje had colonized Jeju island and the southern part of Japan called Khusu.[citation needed] Baekje's cultures had influenced Goguryeo, Silla and also Japan which caused the Asuka culture to occur.[citation needed]

Baekje played a fundamental role in transmitting cultural developments, including Chinese characters and Buddhism, into ancient Japan.[citation needed] Baekje was conquered by an alliance of Silla and Tang forces in 660.

Silla

According to Korean records, in 57 B.C.E., Seorabeol (or Saro, later Silla) in the southeast of the peninsula unified and expanded the confederation of city-states known as Jinhan. Although Samguk-sagi records that Silla was the earliest-founded of the three kingdoms, other written and archaeological records indicate that Silla was likely the last of the three to establish a centralized government.

Renamed from Saro to Silla in 503, the kingdom annexed the Gaya confederacy (which in turn had absorbed Byeonhan earlier) in the first half of the 6th Century. Goguryeo and Baekje responded by forming an alliance. To cope with invasions from Goguryeo and Baekje, Silla deepened its relations with the Tang Dynasty, with her newly-gained access to the Yellow Sea making direct contact with the Tang possible. After the conquest of Goguryeo and Baekje with her Tang allies, the Silla kingdom drove the Tang forces out of the peninsula and occupied the lands south of Pyongyang.

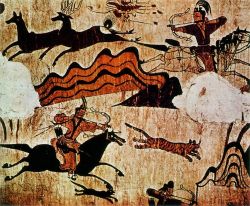

The capital of Silla was Seorabeol (now Gyeongju). Buddhism became the official religion in 528. The remaining material culture from the kingdom of Silla including unique gold metalwork shows influence from the northern nomadic steppes, differentiating it from the culture of Goguryeo and Baekje where Chinese influence was more pronounced.

Other states

Other smaller states existed in Korea before and during this period:

- Gaya confederacy, until annexed by Silla

- Dongye, Okjeo, and Buyeo, all three conquered by Goguryeo

- Usan (Ulleung-do) tributary of Silla

- Tamna (Jeju-do) tributary of Baekje

Unification

Allied with China under the Tang dynasty, Silla conquered Goguryeo in 668, after having already conquered Gaya in 562 and Baekje in 660, thus ushering in the period of Unified Silla to the south and Balhae to the north.

Archaeological perspectives on the Three Kingdoms of Korea

Archaeologists use theoretical guidelines derived from anthropology, ethnology, analogy, and ethnohistory to the concept of what defines a state-level society. This is different from the concept of state (guk or Sino ko: 國, walled-town state, etc) in the discipline of Korean History. In anthropological archaeology the presence of urban centres (especially capitals), monumental architecture, craft specialization and standardization of production, ostentatious burials, writing or recording systems, bureaucracy, demonstrated political control of geographical areas that are usually larger in area than a single river valley, etc make up some of these correlates that define states (Rhee and Choi 1992). Among the archaeology sites dating to the Three Kingdoms of Korea, hundreds of cemeteries with thousands of burials have been excavated. The vast majority of archaeological evidence of the Three Kingdoms Period of Korea consists of burials, but since the 1990s there has been a great increase in the archaeological excavations of industrial production sites, roads, palace grounds and elite precincts, ceremonial sites, commoner households, and fortresses due to the salvage archaeology arising from the frenetic pace of modern Korean economic development.

Formation of Goguryeo, Silla, and Baekje States (c. 0 – A.D. 300/400)

Some individual correlates of complex societies are found in the chiefdoms of Korea that date back to c. 700 B.C.E. (e.g. see Igeum-dong, Songguk-ri) (Bale and Ko 2006; Rhee and Choi 1992). However, the best evidence from the vast archaeological record in Korea indicates that states formed on the Korean peninsula between 300 B.C.E. and A.D. 300/400 (Barnes 2001, 2004; Kang 1995, 2000; Lee 1998; Pai 1989). However, archaeologists are not prepared to suggest that this means there were states in the B.C. era, and so they refer to the polities that formed before the 4th century C.E. as chiefdoms. It is some time in the 4th century C.E. (A.D. 300-400) that many individual correlates of state societies come together to the point that state-level societies can be confidently identified using the copious and incredibly rich data provided by the many excavations that have taken place in Korea since the mid-20th century.

Evidence from burials

Lee Sung-joo analyzes variability in many of the elite cemeteries of the territories of Silla and Gaya polities and finds that as late as the 2nd century C.E. there was intra-cemetery variation in the distribution of prestige grave goods but no hierarchical differences on a regional scale between cemeteries. Archaeological evidence shows that near the end of the 2nd century C.E. interior space in elite burials increased with the increasing use of wooden chamber burial construction techniques by Samhan elites. In the 3rd century C.E. a pattern developed in which single elite cemeteries that were higher in status than all the other cemeteries were established along ridgelines at high elevations. Furthermore, the uppermost elite were buried in large-scale tombs established at the highest points of a given cemetery (Lee 1998). Cemeteries with 'uppermost elite' mounded burials such as Okseong-ri, Yangdong-ri, Daeseong-dong, and Bokcheon-dong display this pattern.

Evidence from factory-scale production of pottery and roof-tiles

Lee Sung-joo argues that, in addition to the development of regional political hierarchies as seen through analysis of burials, variation in types of pottery production gradually disappears and full-time specialization is the only recognizable kind of pottery production from the end of the 4th century C.E. At the same time the production centres for pottery became highly centralized and vessels became standardized (Lee 1998).

Centralization and elite control of production is demonstrated by the results of the archaeological excavations at Songok-dong and Mulcheon-ni in Gyeongju. These sites are part of what was an interconnected and sprawling industrial site on the northeast outskirts of the Silla capital. Songok-dong and Mulcheon-ni are an example of the large-scale of specialized factory-style production in the Three Kingdoms and Unified Silla Periods. The site was excavated in the late 1990s, and archaeologists found the remains of many production features such as pottery kilns, roof-tile kilns, charcoal kilns, as well as the remains of buildings and workshops associated with production. The production features were built along a line of low hilltops and gentle slopes above the valley floor. Most of the artifacts excavated by archaeologists were production debris and tools. The results of the archaeological excavations at the Songok-dong and Mulcheon-ni sites help us to gain a deeper understanding of the high level and intensity of production that began in the 4th century C.E.

Capital cities, elite precincts, and monumental architecture

Since 1976, continuing archaeological excavations concentrated in the southeastern part of modern Gyeongju have revealed parts of the so-called Silla Wanggyeong (Silla capital). A number of excavations over the years have revealed temples such as Hwangnyongsa, Bunhwangsa, Heungryunsa, and 30 other sites.

Elements of Baekje capitals have also been excavated such as the Mongcheon Fortress and Pungnap Fortress.

See also

- Samguk Yusa

- History of Korea

- List of Korean monarchs

- List of Korea-related topics

- Korean Pottery

- Korean Pottery: Categorized by Periods

- Hwangnyongsa

- Heavenly Horse Tomb

- Tribute

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bale, Martin T. (1998). Further investigations of Ko-Silla tomb social ranking using archaeological quantitative analysis techniques. Jinruishi Kenkyu [Journal of the Society of Human History] 10:54-63.

- Bale, Martin T. and Ko, Min-jung (2006). Craft Production and Social Change in Mumun Pottery Period Korea. Asian Perspectives 45(2):159-187.

- Barnes, Gina L. (2001). State formation in Korea: Historical and archaeological perspectives. Richmond, Surrey: Curzon. ISBN 0-7007-1323-9

- Barnes, Gina L. (2004). The emergence and expansion of Silla from an archaeological perspective. Korean Studies 28:15-48.

- Best, J.W. (2003). Buddhism and polity in early sixth-century Paekche. Korean Studies 26(2), 165-215.

- Kang, Bong-won. (1995). The role of warfare in the formation of state in Korea: Historical and archaeological approaches. PhD dissertation. University of Oregon, Eugene. Ann Arbor: University Microfilms.

- Kang, Bong-won. (2000). A test of increasing warfare in the Samguk Sagi against the archaeological remains in Yongnam, South Korea. Journal of East Asian Archaeology 2(2-4):139-197.

- Lee, K. (1984). A New History of Korea. Tr. by E.W. Wagner & E.J. Schulz, based on 1979 rev. ed. Seoul: Ilchogak.

- Lee, Sung-joo. 1998. Silla - Gaya Sahwoe-eui Giwon-gwa Seongjang [The Rise and Growth of Society in Silla and Gaya]. Seoul: Hakyeon Munhwasa.

- Na H.L. (2003). Ideology and religion in ancient Korea. Korea Journal 43(4), 10-29.[1]

- Nelson, Sarah M. (1993). The archaeology of Korea. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Pai, Hyung Il. (1989). Lelang and the "interaction sphere": An alternative approach to Korean state formation. Archaeological Review from Cambridge 8(1):64-75.

- Pearson R, J.W. Lee, W.Y. Koh, and A. Underhill. (1989). Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 8(1):1-50.

- Rhee, S.N. and M.L. Choi. 1992. Emergence of complex society in Korea. Journal of World Prehistory 6(1):51-95.

- http://www.chungdong.or.kr/highroom/history/map/index.htm

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.