Difference between revisions of "Spanish Armada" - New World Encyclopedia

({{Contracted}}) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (22 intermediate revisions by 12 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Ebcompleted}}{{approved}}{{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Paid}}{{copyedited}}{{2Copyedited}} |

| − | :'' | + | {{Infobox Military Conflict |

| + | |conflict=Battle of Gravelines | ||

| + | |partof=the [[Anglo-Spanish War (1585)|Anglo-Spanish War]] | ||

| + | |image=[[Image:Loutherbourg-Spanish_Armada.jpg|300px|]] | ||

| + | |caption=''Defeat of the Spanish Armada'', 1588-[[08-08]] by [[Philippe-Jacques de Loutherbourg]], painted 1797, depicts the battle of Gravelines. | ||

| + | |date=August 8 1588 | ||

| + | |place=[[English Channel]], near [[Gravelines]], [[France]] (then part of the [[Netherlands]]) | ||

| + | |result=Strategic English/Dutch victory<br/>Tactical draw | ||

| + | |combatant1=[[Image:Flag of England.svg|border|22px]] [[England]]<br/>[[Image:Prinsenvlag.svg|border|22px]] [[Dutch Republic]] | ||

| + | |combatant2=[[Image:Flag of New Spain.svg|border|22px]] [[Spain]] | ||

| + | |commander1=[[Charles Howard, 1st Earl of Nottingham|Charles Howard]]<br/>[[Francis Drake]] | ||

| + | |commander2=[[Alonso de Guzman El Bueno, 7th Duke of Medina Sidonia|Duke of Medina Sidonia]] | ||

| + | |strength1=34 warships<br/>163 armed merchant vessels | ||

| + | |strength2=22 [[galleons]]<br/>108 armed merchant vessels | ||

| + | |casualties1=50–100 dead<br/>~400 wounded | ||

| + | |casualties2=600 dead,<br/>800 wounded,<br/>397 captured,<br/>4 merchant ships sunk or captured | ||

| + | }} | ||

| − | The '''Spanish Armada''' or | + | The '''Spanish Armada''' or '''Great Armada''' was the [[Spain|Spanish]] fleet that sailed against [[England]] under the command of the [[Alonso de Guzman El Bueno, 7th Duke of Medina Sidonia|Duke of Medina Sidona]] in 1588. The Armada consisted of about 130 warships and converted merchant ships. |

| − | The Armada was sent by | + | The Armada was sent by King [[Philip II of Spain]], who had been [[king consort]] of England until the death of his wife, [[Mary I of England]], thirty years earlier. The purpose of the expedition was to escort the [[Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma|Duke of Parma's]] army of [[tercio]]s from the [[Spanish Netherlands]] across the [[North Sea]] for a landing in south-east England. Once the army had suppressed English support for the [[Dutch Republic|United Provinces]]—part of the Spanish Netherlands—it was intended to cut off attacks against [[Spanish Empire|Spanish possessions]] in the [[New World]] and the Atlantic [[Spanish treasure fleet|treasure fleet]]s. It was also hoped to reverse the [[English Reformation|Protestant Reformation in England]], and to this end the expedition was supported by [[Pope Sixtus V]], with the promise of a subsidy should it make land. The [[British Empire]] was just beginning with colonies in the Americas. [[Protestant|Protestantism]] was taking root, and a Spanish victory would have compromised this religious transformation. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | The expedition was the most significant engagement of the undeclared [[Anglo–Spanish War (1585)|Anglo–Spanish War]] (1585–1604). The victory was acclaimed by the English as their greatest since [[Battle of Agincourt|Agincourt]], and the boost to national pride lasted for years. The repulse of Spanish naval might gave heart to the Protestant cause across [[Europe]], and the belief that [[God]] was behind the Protestant cause was shown by the creating of commemorative medals bearing the inscription, "He blew with His winds, and they were scattered." | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | Victory over the Armada ended the threat of Spanish invasion, yet by no means did this English victory swing naval dominance towards the English at the expense of the Spanish.<ref>History Buff, [http://www.historybuff.com/library/refarmada4.html The Spanish Armada.] Retrieved August 20, 2007.</ref> In fact, with the failure of an [[English Armada]] the following year, Spanish naval dominance would increase. Britain's navy did not truly rule the seas until after the [[Battle of Trafalgar]] in the early nineteenth century.<ref>Michael Lewis, ''The Spanish Armada'' (New York: T.Y. Crowell Co., 1968).</ref> | ||

| + | {{Campaignbox Anglo-Spanish War}} | ||

==Execution== | ==Execution== | ||

| − | [[ | + | On May 28, 1588, the Armada, with around 130 ships, 8,000 sailors and 18,000 soldiers, 1,500 brass guns and 1,000 iron guns, set sail from [[Lisbon]] in [[Portugal]], headed for the [[English Channel]]. An army of 30,000 men stood in the Spanish Netherlands, waiting for the fleet to arrive. The plan was to land the original force in Plymouth and transfer the land army to somewhere near London, mustering 55,000 men, a huge army for this time. The English fleet was prepared and waiting in Plymouth for news of Spanish movements. It took until May 30 for all of the Armada to leave port and, on the same day, Elizabeth's ambassador in the Netherlands, Dr [[Valentine Dale]], met Parma's representatives to begin peace negotiations. On July 17, negotiations were abandoned. |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | + | Delayed by bad weather, the Armada was not sighted in England until July 19, when it appeared off [[The Lizard]] in [[Cornwall]]. The news was conveyed to London by a sequence of beacons that had been constructed the length of the south coast of England. That same night, 55 ships of the English fleet set out in pursuit from [[Plymouth]] and came under the command of [[Charles Howard, 1st Earl of Nottingham|Lord Howard of Effingham]] (later Earl of Nottingham) and Sir [[John Hawkins]]. However, Hawkins acknowledged his subordinate, [[Sir Francis Drake]], as the more experienced naval commander and gave him some control during the campaign. In order to execute their "line ahead" attack, the English tacked upwind of the Armada, thus gaining a significant maneuvering advantage. | |

| − | + | Over the next week there followed two inconclusive engagements, at [[Eddystone]] and the [[Isle of Portland]]. At the [[Isle of Wight]], the Armada had the opportunity to create a temporary base in protected waters and wait for word from Parma's army. In a full-scale attack, the English fleet broke into four groups, with Drake coming in with a large force from the south. At that critical moment, Medina Sidonia sent reinforcements south and ordered the Armada back into the open sea in order to avoid sandbanks. This left two Spanish wrecks, and with no secure harbors nearby the Armada sailed on to Calais, without regard to the readiness of Parma's army. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | On July 27, the Spanish anchored off [[Calais]] in a crescent-shaped, tightly-packed defensive formation, not far from Parma's army of 16,000, which was waiting at [[Dunkirk, France|Dunkirk]]. There was no deep-water port along that coast of France and the [[Low Countries]] where the fleet might shelter—always a major difficulty for the expedition—and the Spanish found themselves vulnerable as night drew on. | |

| − | + | At midnight of July 28, the English set eight fireships (filled with pitch, gunpowder, and tar) alight and sent them downwind among the closely-anchored Spanish vessels. The Spanish feared that these might prove as deadly as the "[[hellburners]]"<ref>Drizzle, [http://www.drizzle.com/~celyn/jherek/16thMilSci.pdf Hellburners.] Retrieved August 20, 2007.</ref> used against them to deadly effect at the [[Siege of Antwerp (1584-1585)|Siege of Antwerp]].<ref>Foliosoc.co.uk, The Spanish Armada.</ref> Two were intercepted and towed away, but the others bore down on the fleet. Medina Sidonia's flagship, and a few other of the principal warships, held their positions, but the rest of the fleet cut their cables and scattered in confusion, with the result that only one Spanish ship was burned. But the fireships had managed to break the crescent formation, and the fleet now found itself too close to Calais in the rising south-westerly wind to recover its position. In their haste to escape quickly, many Spanish ships cut their anchor lines; the loss of their anchors would prove important later in the campaign. The lighter English ships closed in for battle at Gravelines. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | At midnight of | ||

===Battle of Gravelines=== | ===Battle of Gravelines=== | ||

| − | + | [[Gravelines]] was then part of [[Flanders]] in the [[Spanish Netherlands]], close to the border with France and the closest Spanish territory to England. Medina-Sidonia tried to reform his fleet there, and was reluctant to sail further east owing to the danger from the shoals off Flanders, from which his Dutch enemies had removed the sea-marks. The Spanish army had been expected to join the fleet in barges sent from ports along the Flemish coast, but communications were far more difficult than anticipated, and without notice of the Armada's arrival Parma needed another six days to bring his troops up, while Medina-Sidonia waited at anchor. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The English had learned much of the Armada's strengths and weaknesses during the skirmishes in the English Channel, and accordingly conserved their heavy shot and powder prior to their attack at Gravelines on August 8. During the battle, the Spanish heavy guns proved unwieldy, and their gunners had not been trained to reload—in contrast to their English counterparts, they fired once and then jumped to the rigging to attend to their main task as marines ready to board enemy ships. Evidence from wrecks in [[Ireland]] shows that much of the Armada's ammunition was never spent. | |

| − | + | With its superior maneuverability, the English fleet provoked Spanish fire while staying out of range. Once the Spanish had loosed their heavy shot, the English then closed, firing repeated and damaging broadsides into the enemy ships. This superiority also enabled them to maintain a position to [[windward]] so that the heeling Armada hulls were exposed to damage below the water-line. | |

| − | + | The main handicap for the Spanish was their determination to board the enemy's ships and thrash out a victory in hand-to-hand fighting. This had proved effective at the [[Battle of Lepanto]] in 1571, but the English were aware of this Spanish strength and avoided it. | |

| − | + | Eleven Spanish ships were lost or damaged (though the most seaworthy Atlantic-class vessels escaped largely unscathed). The Armada suffered nearly 2,000 battle casualties before the English fleet ran out of ammunition. English casualties in the battle were far fewer, in the low hundreds. The Spanish plan to join with Parma's army had been defeated, and the English had afforded themselves some breathing space. But the Armada's presence in northern waters still posed a great threat to England. | |

===Pursuit=== | ===Pursuit=== | ||

| − | + | On the day after Gravelines, the wind had backed, southerly, enabling Medina Sidonia to move the Armada northward (away from the French coast). Although their shot lockers were almost empty, the English pursued and harried the Spanish fleet, in an attempt to prevent it returning to escort Parma. On August 12, Howard called a halt to the chase in the latitude of the [[Firth of Forth]] off [[Scotland]]. But by that point, the Spanish were suffering from thirst and exhaustion. The only option left to Medina Sidonia was to chart a course home to Spain, along the most hazardous parts of the Atlantic seaboard. | |

===Tilbury speech=== | ===Tilbury speech=== | ||

| − | + | The threat of invasion from the Netherlands had not yet been discounted, and [[Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester]] maintained a force of 4,000 soldiers at [[West Tilbury]], Essex, to defend the estuary of the [[River Thames]] against any incursion up-river towards London. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[ | + | On August 8, [[Queen Elizabeth]] went to Tilbury to encourage her forces, and the next day gave to them what is probably her most famous speech: |

| + | <blockquote>I have come amongst you as you see, at this time, not for my recreation and disport, but being resolved in the midst and heat of the battle to live or die amongst you all, to lay down for my God and for my kingdom, and for my people, my honor and my blood, even in the dust. I know I have the body of a weak and feeble woman, but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of a king of England too.</blockquote> | ||

===The return to Spain=== | ===The return to Spain=== | ||

| − | + | The Spanish fleet sailed around [[Scotland]] and [[Ireland]] into the North Atlantic. The ships were beginning to show wear from the long voyage, and some were kept together by having their hulls bundled up with cables. Supplies of food and water ran short, and the cavalry horses were driven overboard into the sea. Shortly after reaching the [[latitude]] of Ireland, the Armada ran straight into a [[hurricane]]—to this day, it remains one of the northernmost on record. The hurricane scattered the fleet and drove some two dozen vessels onto the coast of Ireland. Because so many Spanish vessels had lost their anchors during the escape from the English fireships, they were unable to keep themselves from being driven onto the deadly Irish shore. | |

| − | + | A new theory suggests that the Spanish fleet failed to account for the effect of the [[Gulf Stream]]. Therefore, they were much closer to Ireland than planned, a devastating navigational error. This was during the "[[Little Ice Age]]" and the Spanish were not aware that conditions were far colder and more difficult than they had expected for their trip around the north of Scotland and Ireland. As a result, many more ships and sailors were lost to cold and stormy weather than in combat actions. | |

| − | + | Following the storm, it is reckoned that 5,000 men died, whether by drowning and starvation or by [[execution]] at the hands of English forces in Ireland. The reports from Ireland abound with strange accounts of brutality and survival, and attest on occasion to the brilliance of Spanish seamanship. Survivors did receive help from the Gaelic Irish, with many escaping to Scotland and beyond. | |

| − | + | In the end, 67 ships and around 10,000 men survived. Many of the men were near death from disease, as the conditions were very cramped and most of the ships ran out of food and water. Many more died in Spain, or on hospital ships in Spanish harbors, from diseases contracted during the voyage. It was reported that, when Philip II learned of the result of the expedition, he declared, "I sent my ships to fight against the English, not against the elements." Although disappointed, he forgave the Duke of Medina Sidonia. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

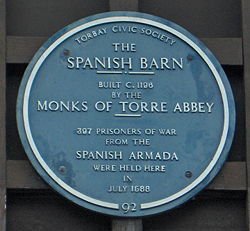

[[Image:The Spanish Barn, Torquay.jpg|250px|right]] | [[Image:The Spanish Barn, Torquay.jpg|250px|right]] | ||

[[Image:The Spanish Barn plaque, Torquay.jpg|250px|right]] | [[Image:The Spanish Barn plaque, Torquay.jpg|250px|right]] | ||

| + | English losses were comparatively few, and none of their ships were sunk. But after the victory, typhus and [[dysentery]] killed many sailors and troops (estimated at 6,000–8,000) as they languished for weeks in readiness for the Armada's return out of the North Sea. Then a demoralizing dispute occasioned by the government's fiscal shortfalls left many of the English defenders unpaid for months, which was in contrast to the assistance given by the Spanish government to its surviving men. | ||

| − | English | + | ==Consequences== |

| + | For England, the greatest result was to prevent the Spanish from invading the country, and thereby protected the young Protestant Reformation that would transform English society and lead to the development of modern democracy in the [[United States]], the [[United Kingdom]] and throughout the world. In this sense, the victory over the Spanish Armada was a world-historical event. | ||

| − | + | The repulse of Spanish naval might gave heart to the Protestant cause across [[Europe]], and the belief that [[God]] was behind the Protestant cause was shown by the creating of commemorative medals bearing the inscription, "He blew with His winds, and they were scattered." The boost to English national pride lasted for years, and Elizabeth's legend persisted and grew well after her death. | |

| − | + | Although the victory was acclaimed by the English as their greatest since [[Battle of Agincourt|Agincourt]], an attempt in the following year to press home their advantage failed, when an [[English Armada]] returned to port with little to show for its efforts. The supply of troops and munitions from England to Philip II's enemies in the Netherlands and France continued and high seas buccaneering against the Spanish persisted but with decreasing success. The Anglo-Spanish war thereafter generally favored Spain. | |

| − | + | It was half a century later when the Dutch broke Spanish dominance at sea in the [[Battle of the Downs]] in (1639). The strength of Spain's ''[[tercios]]''—the dominant fighting unit in European land campaigns for over a century—was broken by the French at the [[Battle of Rocroi]] (1643). | |

| − | + | ==Notes== | |

| − | + | <references/> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | *'' | + | * Falls, Cyril. ''Elizabeth's Irish Wars'' London, 1996. ISBN 0094772207 |

| − | + | * Kelsey, Harry. ''Sir Francis Drake: the Queen's pirate''. New Haven: Yale University Press 1998. ISBN 9780300071825 | |

| − | + | * Mattingley, Garrett. ''The defeat of the Spanish Armada''. London: Penguin 1988. ISBN 9780140077643 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | ==External links== | ||

| + | All links retrieved February 7, 2023. | ||

| − | [ | + | *[http://www.bl.uk/learning/histcitizen/uk/armada/intro.html Elizabeth I and the Spanish Armada.] |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[ | + | [[Category:History]] |

| − | [[ | + | [[Category:Politics and social sciences]] |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | {{credit| | + | {{credit|151814336}} |

Latest revision as of 15:18, 27 April 2023

| Battle of Gravelines | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Anglo-Spanish War | |||||||

Defeat of the Spanish Armada, 1588-08-08 by Philippe-Jacques de Loutherbourg, painted 1797, depicts the battle of Gravelines. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Combatants | |||||||

| Commanders | |||||||

| Charles Howard Francis Drake |

Duke of Medina Sidonia | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 34 warships 163 armed merchant vessels |

22 galleons 108 armed merchant vessels | ||||||

| Casualties | |||||||

| 50–100 dead ~400 wounded |

600 dead, 800 wounded, 397 captured, 4 merchant ships sunk or captured | ||||||

The Spanish Armada or Great Armada was the Spanish fleet that sailed against England under the command of the Duke of Medina Sidona in 1588. The Armada consisted of about 130 warships and converted merchant ships.

The Armada was sent by King Philip II of Spain, who had been king consort of England until the death of his wife, Mary I of England, thirty years earlier. The purpose of the expedition was to escort the Duke of Parma's army of tercios from the Spanish Netherlands across the North Sea for a landing in south-east England. Once the army had suppressed English support for the United Provinces—part of the Spanish Netherlands—it was intended to cut off attacks against Spanish possessions in the New World and the Atlantic treasure fleets. It was also hoped to reverse the Protestant Reformation in England, and to this end the expedition was supported by Pope Sixtus V, with the promise of a subsidy should it make land. The British Empire was just beginning with colonies in the Americas. Protestantism was taking root, and a Spanish victory would have compromised this religious transformation.

The expedition was the most significant engagement of the undeclared Anglo–Spanish War (1585–1604). The victory was acclaimed by the English as their greatest since Agincourt, and the boost to national pride lasted for years. The repulse of Spanish naval might gave heart to the Protestant cause across Europe, and the belief that God was behind the Protestant cause was shown by the creating of commemorative medals bearing the inscription, "He blew with His winds, and they were scattered."

Victory over the Armada ended the threat of Spanish invasion, yet by no means did this English victory swing naval dominance towards the English at the expense of the Spanish.[1] In fact, with the failure of an English Armada the following year, Spanish naval dominance would increase. Britain's navy did not truly rule the seas until after the Battle of Trafalgar in the early nineteenth century.[2]

| Anglo-Spanish War |

|---|

| San Juan de Ulúa – Gravelines – Corunna – Lisbon – Spanish Main – Azores |

Execution

On May 28, 1588, the Armada, with around 130 ships, 8,000 sailors and 18,000 soldiers, 1,500 brass guns and 1,000 iron guns, set sail from Lisbon in Portugal, headed for the English Channel. An army of 30,000 men stood in the Spanish Netherlands, waiting for the fleet to arrive. The plan was to land the original force in Plymouth and transfer the land army to somewhere near London, mustering 55,000 men, a huge army for this time. The English fleet was prepared and waiting in Plymouth for news of Spanish movements. It took until May 30 for all of the Armada to leave port and, on the same day, Elizabeth's ambassador in the Netherlands, Dr Valentine Dale, met Parma's representatives to begin peace negotiations. On July 17, negotiations were abandoned.

Delayed by bad weather, the Armada was not sighted in England until July 19, when it appeared off The Lizard in Cornwall. The news was conveyed to London by a sequence of beacons that had been constructed the length of the south coast of England. That same night, 55 ships of the English fleet set out in pursuit from Plymouth and came under the command of Lord Howard of Effingham (later Earl of Nottingham) and Sir John Hawkins. However, Hawkins acknowledged his subordinate, Sir Francis Drake, as the more experienced naval commander and gave him some control during the campaign. In order to execute their "line ahead" attack, the English tacked upwind of the Armada, thus gaining a significant maneuvering advantage.

Over the next week there followed two inconclusive engagements, at Eddystone and the Isle of Portland. At the Isle of Wight, the Armada had the opportunity to create a temporary base in protected waters and wait for word from Parma's army. In a full-scale attack, the English fleet broke into four groups, with Drake coming in with a large force from the south. At that critical moment, Medina Sidonia sent reinforcements south and ordered the Armada back into the open sea in order to avoid sandbanks. This left two Spanish wrecks, and with no secure harbors nearby the Armada sailed on to Calais, without regard to the readiness of Parma's army.

On July 27, the Spanish anchored off Calais in a crescent-shaped, tightly-packed defensive formation, not far from Parma's army of 16,000, which was waiting at Dunkirk. There was no deep-water port along that coast of France and the Low Countries where the fleet might shelter—always a major difficulty for the expedition—and the Spanish found themselves vulnerable as night drew on.

At midnight of July 28, the English set eight fireships (filled with pitch, gunpowder, and tar) alight and sent them downwind among the closely-anchored Spanish vessels. The Spanish feared that these might prove as deadly as the "hellburners"[3] used against them to deadly effect at the Siege of Antwerp.[4] Two were intercepted and towed away, but the others bore down on the fleet. Medina Sidonia's flagship, and a few other of the principal warships, held their positions, but the rest of the fleet cut their cables and scattered in confusion, with the result that only one Spanish ship was burned. But the fireships had managed to break the crescent formation, and the fleet now found itself too close to Calais in the rising south-westerly wind to recover its position. In their haste to escape quickly, many Spanish ships cut their anchor lines; the loss of their anchors would prove important later in the campaign. The lighter English ships closed in for battle at Gravelines.

Battle of Gravelines

Gravelines was then part of Flanders in the Spanish Netherlands, close to the border with France and the closest Spanish territory to England. Medina-Sidonia tried to reform his fleet there, and was reluctant to sail further east owing to the danger from the shoals off Flanders, from which his Dutch enemies had removed the sea-marks. The Spanish army had been expected to join the fleet in barges sent from ports along the Flemish coast, but communications were far more difficult than anticipated, and without notice of the Armada's arrival Parma needed another six days to bring his troops up, while Medina-Sidonia waited at anchor.

The English had learned much of the Armada's strengths and weaknesses during the skirmishes in the English Channel, and accordingly conserved their heavy shot and powder prior to their attack at Gravelines on August 8. During the battle, the Spanish heavy guns proved unwieldy, and their gunners had not been trained to reload—in contrast to their English counterparts, they fired once and then jumped to the rigging to attend to their main task as marines ready to board enemy ships. Evidence from wrecks in Ireland shows that much of the Armada's ammunition was never spent.

With its superior maneuverability, the English fleet provoked Spanish fire while staying out of range. Once the Spanish had loosed their heavy shot, the English then closed, firing repeated and damaging broadsides into the enemy ships. This superiority also enabled them to maintain a position to windward so that the heeling Armada hulls were exposed to damage below the water-line.

The main handicap for the Spanish was their determination to board the enemy's ships and thrash out a victory in hand-to-hand fighting. This had proved effective at the Battle of Lepanto in 1571, but the English were aware of this Spanish strength and avoided it.

Eleven Spanish ships were lost or damaged (though the most seaworthy Atlantic-class vessels escaped largely unscathed). The Armada suffered nearly 2,000 battle casualties before the English fleet ran out of ammunition. English casualties in the battle were far fewer, in the low hundreds. The Spanish plan to join with Parma's army had been defeated, and the English had afforded themselves some breathing space. But the Armada's presence in northern waters still posed a great threat to England.

Pursuit

On the day after Gravelines, the wind had backed, southerly, enabling Medina Sidonia to move the Armada northward (away from the French coast). Although their shot lockers were almost empty, the English pursued and harried the Spanish fleet, in an attempt to prevent it returning to escort Parma. On August 12, Howard called a halt to the chase in the latitude of the Firth of Forth off Scotland. But by that point, the Spanish were suffering from thirst and exhaustion. The only option left to Medina Sidonia was to chart a course home to Spain, along the most hazardous parts of the Atlantic seaboard.

Tilbury speech

The threat of invasion from the Netherlands had not yet been discounted, and Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester maintained a force of 4,000 soldiers at West Tilbury, Essex, to defend the estuary of the River Thames against any incursion up-river towards London.

On August 8, Queen Elizabeth went to Tilbury to encourage her forces, and the next day gave to them what is probably her most famous speech:

I have come amongst you as you see, at this time, not for my recreation and disport, but being resolved in the midst and heat of the battle to live or die amongst you all, to lay down for my God and for my kingdom, and for my people, my honor and my blood, even in the dust. I know I have the body of a weak and feeble woman, but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of a king of England too.

The return to Spain

The Spanish fleet sailed around Scotland and Ireland into the North Atlantic. The ships were beginning to show wear from the long voyage, and some were kept together by having their hulls bundled up with cables. Supplies of food and water ran short, and the cavalry horses were driven overboard into the sea. Shortly after reaching the latitude of Ireland, the Armada ran straight into a hurricane—to this day, it remains one of the northernmost on record. The hurricane scattered the fleet and drove some two dozen vessels onto the coast of Ireland. Because so many Spanish vessels had lost their anchors during the escape from the English fireships, they were unable to keep themselves from being driven onto the deadly Irish shore.

A new theory suggests that the Spanish fleet failed to account for the effect of the Gulf Stream. Therefore, they were much closer to Ireland than planned, a devastating navigational error. This was during the "Little Ice Age" and the Spanish were not aware that conditions were far colder and more difficult than they had expected for their trip around the north of Scotland and Ireland. As a result, many more ships and sailors were lost to cold and stormy weather than in combat actions.

Following the storm, it is reckoned that 5,000 men died, whether by drowning and starvation or by execution at the hands of English forces in Ireland. The reports from Ireland abound with strange accounts of brutality and survival, and attest on occasion to the brilliance of Spanish seamanship. Survivors did receive help from the Gaelic Irish, with many escaping to Scotland and beyond.

In the end, 67 ships and around 10,000 men survived. Many of the men were near death from disease, as the conditions were very cramped and most of the ships ran out of food and water. Many more died in Spain, or on hospital ships in Spanish harbors, from diseases contracted during the voyage. It was reported that, when Philip II learned of the result of the expedition, he declared, "I sent my ships to fight against the English, not against the elements." Although disappointed, he forgave the Duke of Medina Sidonia.

English losses were comparatively few, and none of their ships were sunk. But after the victory, typhus and dysentery killed many sailors and troops (estimated at 6,000–8,000) as they languished for weeks in readiness for the Armada's return out of the North Sea. Then a demoralizing dispute occasioned by the government's fiscal shortfalls left many of the English defenders unpaid for months, which was in contrast to the assistance given by the Spanish government to its surviving men.

Consequences

For England, the greatest result was to prevent the Spanish from invading the country, and thereby protected the young Protestant Reformation that would transform English society and lead to the development of modern democracy in the United States, the United Kingdom and throughout the world. In this sense, the victory over the Spanish Armada was a world-historical event.

The repulse of Spanish naval might gave heart to the Protestant cause across Europe, and the belief that God was behind the Protestant cause was shown by the creating of commemorative medals bearing the inscription, "He blew with His winds, and they were scattered." The boost to English national pride lasted for years, and Elizabeth's legend persisted and grew well after her death.

Although the victory was acclaimed by the English as their greatest since Agincourt, an attempt in the following year to press home their advantage failed, when an English Armada returned to port with little to show for its efforts. The supply of troops and munitions from England to Philip II's enemies in the Netherlands and France continued and high seas buccaneering against the Spanish persisted but with decreasing success. The Anglo-Spanish war thereafter generally favored Spain.

It was half a century later when the Dutch broke Spanish dominance at sea in the Battle of the Downs in (1639). The strength of Spain's tercios—the dominant fighting unit in European land campaigns for over a century—was broken by the French at the Battle of Rocroi (1643).

Notes

- ↑ History Buff, The Spanish Armada. Retrieved August 20, 2007.

- ↑ Michael Lewis, The Spanish Armada (New York: T.Y. Crowell Co., 1968).

- ↑ Drizzle, Hellburners. Retrieved August 20, 2007.

- ↑ Foliosoc.co.uk, The Spanish Armada.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Falls, Cyril. Elizabeth's Irish Wars London, 1996. ISBN 0094772207

- Kelsey, Harry. Sir Francis Drake: the Queen's pirate. New Haven: Yale University Press 1998. ISBN 9780300071825

- Mattingley, Garrett. The defeat of the Spanish Armada. London: Penguin 1988. ISBN 9780140077643

External links

All links retrieved February 7, 2023.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.