Spanish-American War

Template:Sprotected

| Spanish-American War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

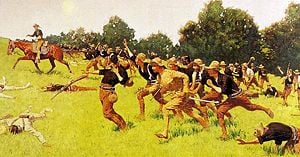

Charge of the Rough Riders at San Juan Hill by Frederic Remington | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Combatants | |||||||||

| Commanders | |||||||||

| Casualties | |||||||||

| 3,289 U.S. dead (only 332 from combat); considerably higher although undetermined Cuban and Filipino casualties | Unknown[1] | ||||||||

The Spanish-American War was a conflict between the Kingdom of Spain and the United States of America that took place from April to August 1898. The war ended in victory for the United States and the end of the Spanish empire in the Caribbean and Pacific. Only 113 days after the outbreak of war, the Treaty of Paris, which ended the conflict, gave the United States control over the former Spanish colonies of Puerto Rico, the Philippines and Guam, and control over the process of independence of Cuba, which was completed in 1902.

Background

Following four centuries of colonization of the Western Hemisphere, by the late nineteenth century Spain was left with only a few scattered possessions in the Pacific Ocean, Africa, and the West Indies. Much of the Spanish Empire had already gained its independence and a number of the areas still under Spanish control were clamoring to do so. Guerrilla forces were operating in the Philippines, and had been present in Cuba since before the 1868-1878 Ten Years' War. The Spanish government did not have the financial resources or the personnel to deal with these revolts and resorted to forcibly emptying the countryside and the filling of the cities with concentration camps (in Cuba)[5] to separate the rebels from their rural support bases. Many hundreds of thousands of Cubans died of starvation and disease in these circumstances - 200,000 alone in the more peaceful western Cuba. The Spaniards also carried out many executions of suspected rebels and harshly treated suspected sympathizers. The Cuban War of Independence saw both Cuban rebels and Spanish troops burning and destroying infrastructure, crops, tools, livestock, and anything else that might aid the enemy. By 1897 the rebels had mostly defeated the Spanish. They were firmly in control of the eastern countryside and the Spanish could only leave urban centers in columns of considerable strength. Public opinion in Cuba favored American intervention. Fueled by reports of inhumanity of the Spanish, a majority of Americans became convinced that an intervention was becoming necessary.

Sinking of the USS Maine

On February 15 1898, an explosion sank the American battleship USS Maine in Havana harbor with a loss of 266 men. Evidence as to the cause of the explosion was inconclusive and contradictory. It may have been an accident, or caused by a Spanish or Cuban mine.

William Randolph Hearst's newspaper in New York, in what became known as yellow journalism, sensationalised the atrocities committed in Cuba. The newspaper included a fake telegram from the Spanish about the sinking of the U.S.S. Maine, embarrassing the U.S. and infuriating the Spanish. Joseph Pulitzer was also a key figure in publicizing the war in New York City. His newspapers, too, exaggerated news of the atrocities to sway popular opinion in favor of intervention.[2] Although Hearst and Pulitzer published inflammatory articles in New York City, major papers elsewhere remained cautious. Americans remained unsure of the cause; most blamed the Spanish for not controlling their harbor.

There were, however, very real pressures pushing toward war within Cuba. Faced with defeat, a lack of money, and resources to continue fighting Spanish occupation, Cuban revolutionary and future president Tomás Estrada Palma, then Head of the Cuban Revolutionary Junta, offered $150 million to purchase Cuba's independence, but Spain refused, as the money did not exist. The Cubans then deftly negotiated and propagandized their cause in the U.S. Congress.

Humanitarian interests dominated American opinion. President William McKinley and House Speaker Thomas Reed worked hard to calm the mood, as did many Republicans, but the pressure from Democrats across the country steadily increased.

Spain could not back down without creating a crisis at home. On the verge of civil war, Spain felt that to surrender to American demands would be politically dangerous. To fight a war against the United States was deemed more acceptable to the Spanish government, even though it expected to lose. That would allow the difficult issue of Cuba to be shed without civil war at home. The U.S. government had considered purchase of Cuba over the years, but had always decided against making an offer. No major American modern leader supported annexing the island because none thought Cuba could be assimilated into the American political system. Much of the island's export business and high technology was already in American hands, and most of Cuba's trade was with the United States. Thus there was no economic need for acquisition of the island, and no major business interests proposed acquisition. Senator John M. Thurston argued that a war would bring more government spending so that, "War with Spain would increase the business and earnings of every American railroad, it would increase the output of every American factory, it would stimulate every branch of industry and domestic commerce." However, most businessmen opposed war and supported McKinley, according to historians' analysis of the business press and statements by business leaders across the country.

The United States Navy had recently grown considerably and been reorganized, but it was still untested, and Navy leaders hoped war would help it prove itself. To this end, the U.S. Navy drew up contingency plans for attacking the Spanish in the Philippines over a year before hostilities broke out.

In Spain, the government was not entirely averse to war. The United States was an unproven power, while the Spanish Navy, however decrepit, had a glorious history, and it was thought it could be a match for its U.S. counterpart. The De Lôme Letter was an example of the doubts of Spain as to whether the United States was powerful enough to defeat them. There was also a widely held notion among Spain's aristocratic leaders that the United States' ethnically mixed army and navy could not endure the pressure of war.

Declaration of war

The main reason for the American declaration of war was Spain's inability to guarantee peace and stability in Cuba [citation needed]. The explosion of the Maine did not cause the war, but it focused American attention on Cuba; the call was for an immediate resolution to the Cuban situation. Spanish minister Práxedes Mateo Sagasta attempted to compromise with an offer to withdraw unpopular officials from Cuba, and yet another proposal for Cuba's autonomy sometime in the future.

The decisive event was probably the speech of Republican Senator Redfield Proctor in mid-March, thoroughly and calmly analyzing the situation and concluding war was the only answer. The business and religious communities, which had opposed war, now switched sides, leaving McKinley and Reed almost alone.[3] Thus, on April 11, McKinley asked Congress for authority to send American troops to Cuba for the purpose of ending the civil war there. On April 19, Congress passed joint resolutions proclaiming Cuba "free and independent" and disclaiming any intentions in Cuba, demanded Spanish withdrawal, and authorized the President to use as much military force as he thought necessary to help Cuban patriots gain freedom from Spain. (This was adopted by Congress from Senator Henry Teller of Colorado as the Teller Amendment, which passed unanimously.) In response, Spain broke off diplomatic relations with the United States. On April 25, Congress declared that a state of war between the United States and Spain had existed since April 21 (later changed to April 20).

Theaters of operation

The Philippines

- For more on engagements in the Philippines, please see Philippine-American War, Philippine Revolution.

The first battle was in the sea near the Philippines where, on May 1, 1898, Commodore George Dewey, commanding the United States Pacific fleet, in a matter of hours, defeated the Spanish squadron, under Admiral Patricio Montojo y Pasarón, without sustaining a casualty, at the Battle of Manila Bay. The success of the Pacific Fleet was due to the Spanish Navy being trapped in the bay.

Meanwhile, Dewey allowed Emilio Aguinaldo to return to the Philippines. Aguinaldo's forces attacked the Spanish on land, successfully defeating them and ended with the Battle of Manila (July 25 1898 - August 13 1898) where the Spanish surrendered Manila but the U.S. Army made a deal to protect them from Filipino persecution.

Cuba

Theodore Roosevelt actively encouraged intervention in Cuba and, while assistant secretary of the Navy, placed the Navy on a war-time footing. He ordered Dewey and the Pacific fleet to the Philippines and he worked with Leonard Wood in convincing the Army to raise an all-volunteer regiment, the 1st U.S. Volunteer Cavalry. Wood was given command of the regiment that became quickly known as the "Rough Riders".

The first action in Cuba was the establishing of a base at Guantánamo Bay on 10 June by U.S. Marines (see 1898 invasion of Guantánamo Bay)

Spanish Admiral Cervera, who had arrived from Spain, held up his naval forces in Santiago harbor where they would be protected from sea attack. Assistant Naval Constructor Richmond Pearson Hobson was soon ordered by Admiral Sampson to sink the collier Merrimac in the harbor to bottle up the fleet. The mission was a failure and Hobson and his crew were captured. They were exchanged on July 6, and Hobson became a national hero; receiving the Medal of Honor in 1933 and becoming a Congressman.

Ground operations in Cuba

The Americans planned to capture the city of Santiago in order to destroy Linares Army and Cervera's fleet, which they must to pass through concentrated Spanish defenses in San Juan Hills and a small town in El Caney. The Americans forces would be aided in Cuba by the pro-independence rebels led by General Calixto García.

On June 22 and June 24, the U.S. V Corps under General William R. Shafter landed at Daiquiri and Siboney East of Santiago and established the American base of operations, unopposed by the Spaniards who had retreated under assault by Cuban land forces. An advance guard of U.S. forces under former Confederate General Joseph Wheeler ignored Cuban scouting parties and orders to proceed with caution. They caught up with and engaged the Spanish rear guard in the Battle of Las Guasimas. Here, U.S. forces were checked momentarily although the Spanish continued their planned retreat. The battle of Las Guasimas showed the U.S.A that the civil war tactics did not work effectively against Spain; they suffered a lot of unnecessary casualties.

Battle of El Caney and San Juan Hill

On July 1 a combined force of about 15,000 American troops in regular infantry, cavalry and volunteer regiments, including Roosevelt and his "Rough Riders," and rebel Cuban forces attacked 1,270 entrenched Spaniards in dangerous frontal assaults at the Battle of El Caney and Battle of San Juan Hill outside of Santiago. [6] More than 200 U.S. soldiers were killed and close to 1,200 wounded [7] in the fighting, The Spaniards suffered less than half the number of casualties. [8] Supporting fire by Gatling guns was critical to the success of the assault [9] [10]. It was then that Cervera decided to escape Santiago two days later.

The Spanish forces at Guantánamo were so isolated by Marines and Cuban forces that they did not know that Santiago was under siege, and their forces in the northern part of the province could not break through Cuban lines. This was not true of the Escario relief column from Manzanillo [11] which fought its way past determined Cuban resistance, but arrived too late to participate in the siege.

Subsequent operations

After the battles of San Juan Hill and El Caney, the action was slowed by the successful defenses at and around Fort Canosa [12]. The campaign turned into a bloody strangling siege.[4] During the nights, Cuban troops were used to dig successive series of progressively advancing "trenches," which were actually raised parapets. Once completed, these parapets were occupied by US troops and a new set of parapets constructed. The US troops, while suffering some losses from Spanish fire, suffered far more casualties from heat exhaustion and mosquito borne disease [5]. At the western approaches to the city Cuban General Calixto Garcia began to encroach on the city, causing much panic and fear of reprisals among the Spanish forces.

The Americans defeated the poorly developed ships of Admiral Cervera as his fleet left the safety of the port of Santiago in the Battle of Santiago de Cuba and gained control of the seas around Cuba.[6] This prevented re-supply of the Spanish forces and also allowed the U.S. to land considerable reserve forces unopposed. Within a month, most of the island was in US or Cuban hands, but they suffered serious casualties from wounds and illness. Soon the Spanish abandoned Havana, under US protection, but the Cubans wanted revenge.

Puerto Rico

During May 1898, Lt. Henry H. Whitney of the United States Fourth Artillery was sent to Puerto Rico on a reconnaissance mission, sponsored by the Army's Bureau of Military Intelligence. He provided maps and information on the Spanish military forces to the U.S. government prior to the invasion. On May 10, U.S. Navy warships were sighted off the coast of Puerto Rico. On May 12, a squadron of 12 U.S. ships commanded by Rear Adm. William T. Sampson bombarded San Juan. During the bombardment, many buildings were shelled. On June 25, the Yosemite blocked San Juan harbor. On July 25, General Nelson A. Miles, with 3,300 soldiers, landed at Guánica and took over the island with little resistance.

Peace treaty

With both of its fleets incapacitated, Spain sued for peace.

Hostilities were halted on August 12, 1898. The formal peace treaty, the Treaty of Paris, was signed in Paris on December 10, 1898 and was ratified by the United States Senate on February 6, 1899. It came into force on April 11, 1899. Cubans participated only as observers.

The United States gained almost all of Spain's colonies, including the Philippines, Guam, and Puerto Rico. Cuba was granted independence, but the United States imposed various restrictions on the new government, including prohibiting alliances with other countries.

On August 14 1898, 11,000 ground troops were sent to occupy the Philippines. When U.S. troops began to take the place of the Spanish in control of the country, warfare broke out between U.S. forces and the Filipinos.

Aftermath

The war resulted in three territorial conquests for the United States, tens of thousands of Spanish and Cubans killed before American intervention, and the deaths of perhaps a quarter of a million Filipinos [13].

The Spanish-American War is significant in American history, as it saw the young nation emerge as a power on the world stage, though with a colonial domain smaller than that of Britain or France. The war marked American entry into world affairs: over the course of the next century, the United States had a large hand in various conflicts around the world. The Panic of 1893 was over by this point, and the United States entered a lengthy and prosperous period of high economic growth, population growth, and technological innovation which would last through the 1920s.

The Spanish-American war marked the effective end of the Spanish empire. Spain had been declining as a great power over most of the previous century. The defeat paradoxically postponed the civil war that had seemed imminent in 1898 and created a renaissance known as the Generation of 1898. Spain, however, would break out into civil war in the 1930s.

Congress had passed the Teller Amendment prior to the war, promising Cuban independence. However, the Senate passed the Platt Amendment as a rider to an Army appropriations bill, forcing a peace treaty on Cuba which prohibited it from signing treaties with other nations or contracting a public debt. Most notoriously, the Amendment granted the United States the right to militarily invade Cuba when it saw fit, a provision on which the United States acted numerous times. The Platt Amendment also provided for the establishment of a permanent American naval base in Cuba, which would lead to the base still in use today at Guantánamo Bay. The Cuban peace treaty of 1903 would govern Cuban-American relations until 1934.

The United States annexed the former Spanish colonies of Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and Guam. The notion of the United States as an imperial power, with foreign colonies, was hotly debated domestically with President McKinley and the Pro-Imperialists winning their way over vocal opposition. The American public largely supported the possession of colonies, but there were many outspoken critics such as Mark Twain, who wrote The War Prayer in protest.

Mark Twain's writings attacked U.S. Army General Frederick Funston with particular ferocity. Funston, who was in the Philippines because, after fighting with Cuban rebel forces [14] [15] he had given his parole [not to fight again in Cuba], is notable for his adroit capture of Emilio Aguinaldo which much decreased the Philippine-American War's intensity, and other deeds which earned him the Medal of Honor [16] and promotion by Lieutenant General Arthur MacArthur, Jr., father of Douglas McArthur

Roosevelt returned to the United States a war hero, soon to be elected governor, and then Vice President.

William Randolph Hearst emerged as a national institution: the first media tycoon in American history. The Hearst papers became so extremely successful at agitating public sentiment in favor of war, that he eventually became an archetypal figure in his own right. He had become more influential than even many politicians, and, at various levels, would be sought after for that influence. Decades later, a young filmmaker named Orson Welles would immortalize the Hearst archetype with Citizen Kane, a portrayal which William Hearst, in later life, would find quite displeasing, though he reportedly never saw the film himself.

Another interesting, but little-noted effect of this short war, was that it served to further cement relations between the American North and South. The war provided both sides a common enemy for the first time since the end of the American Civil War in 1865, and many friendships were formed between soldiers of both Northern and Southern states during their tours of duty. This was an important development as many soldiers in this war were the children of Civil War veterans on both sides, and may have grown up regarding their parents' counterparts as enemies.

Reconciliation between the former Yankee and Confederate soldiers were marked by "Blue-Gray" Reunions and increased political harmony between Northern and Southern politicians. The "Lost Cause" view took hold in the popular imagination and many former Confederate leaders were held in general high esteem nationally. The 1890s also witnessed resurgent racism in the North and the passage of Jim Crow laws that increased segregation of blacks from whites. The Spanish-American War provoked widespread feelings of jingoistic American nationalism that fused often-divergent Northern and Southern public opinion.

The African-American community strongly supported the rebels in Cuba, supported entry into the war, and gained prestige from their wartime performance in the American army. Spokesmen noted that 33 African American seamen had died in the Maine explosion. The most influential black leader, Booker T. Washington argued that his race was ready to fight. War would offer them a chance "to render service to our country that no other race can," because, unlike whites, they were "accustomed" to the "peculiar and dangerous climate" of Cuba. In mid-March, 1898, Washington promised the Secretary of the Navy that war would be answered by "at least ten thousand loyal, brave, strong black men in the south who crave an opportunity to show their loyalty to our land and would gladly take this method of showing their gratitude for the lives laid down and the sacrifices made that the Negro might have his freedom and rights." [7]

In 1904, the United Spanish War Veterans was created from smaller groups of the veterans of the Spanish American War. Today, that organization is defunct, but it left an heir in the form of the Sons of Spanish American War Veterans, created in 1937 at the 39th National Encampment of the United Spanish War Veterans. According to data from the United States Department of Veterans Affairs, the last surviving U.S. veteran of the conflict, Nathan E. Cook, died on September 10, 1992 at the age of 106. (If the data is to be believed, Cook, born October 10 1885, would have been a mere 12 years of age when he served in the war.)

Propaganda in the war

Historians debate the extent to which propaganda—rather than true stories and actual events—caused the war. In the 1890s, while competing over readership of their newspapers in New York City, William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer’s yellow journalism are said to sway public opinion in New York City. They were not influential in the rest of the country. By appealing to the territoriality and ethnocentrism of readers, Hearst and Pulitzer had some influence over American opinion of the Spanish. The Spanish soldiers, portrayed as cruel and bloodthirsty, were accused of countless illegal and immoral acts. Allegations were made that innocent women were strip searched by callous troops, or taken prisoner and thrown into Cuban jails full of violent criminals. These images and stories invoked the public outcry that led to war.

One of the most effective ways to rouse emotion was to portray the victimization of women, the most prominent being Evangelina Betancourt Cisneros. The articles do not only mention Evangelina, but also describe her as an affluent, innocent, and young woman. She was intentionally described this way to invoke a sympathetic response. The response the authors wanted was support for the Cubans. Evangelina Cisneros was, in fact, the daughter of a rebel leader who had been imprisoned. In order to get her father moved to a better prison, Evangelina offered to stay in prison with him. After an incident with a Spanish Colonel, the nature of which is unclear, Evangelina was moved to a much harsher prison.

The Spanish American War also saw the very first use of film in propaganda. A short ninety second film, called Tearing Down the Spanish Flag, produced in 1898, was a simple moving image designed to inspire patriotism and hatred for the Spanish in America. This film, as the title suggests, depicts the removal of the Spanish national flag and its replacement by the Stars and Stripes of America. This film was very effective in rousing its audience.

Military decorations

In the United States, the Spanish-American War was the first large-scale military action since the Civil War, and the conflict produced the first major recognition of individual acts of bravery by soldiers, marines, and sailors alike.

The United States awards and decorations of the Spanish-American War were as follows:

- Medal of Honor (Extreme Acts of Heroism or Bravery)

- Specially Meritorious Service Medal (Navy and Marine Corps Meritorious Actions)

- Spanish Campaign Medal (General Service)

- West Indies Campaign Medal (West Indies Naval Service)

- Sampson Medal (West Indies service under Admiral Sampson)

- Dewey Medal (Battle of Manila Bay Service)

- Spanish War Service Medal (U.S. Army Homeland Service)

- Army of Puerto Rican Occupation Medal (Post-War Occupation Duty)

- Army of Cuban Occupation Medal (Post-War Occupation Duty)

The Spanish Campaign Medal was upgradeable to include the Silver Citation Star to recognize those U.S. Army members who had performed individual acts of heroism. The governments of Spain and Cuba also issued a wide variety of military awards to honor Spanish, Cuban, and Philippine soldiers who had served in the conflict.

Further reading

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Benjamin R. Beede, ed. The War of 1898 and U.S. Interventions, 1898-1934 (1994). an encyclopedia

- Donald H. Dyal, Brian B. Carpenter, Mark A. Thomas; Historical Dictionary of the Spanish American War Greenwood Press, 1996

- Hendrickson, Kenneth E., Jr. The Spanish-American War Greenwood, 2003. short summary

Diplomacy and causes of the war

- James C. Bradford , ed., Crucible of Empire: The Spanish-American War and Its Aftermath (1993), essays on diplomacy, naval and military operations, and historiography.

- Lewis L. Gould, The Spanish-American War and President McKinley (1982)

- Ernest R. May, Imperial Demoracy: The Emergence of America as a Great Power (1961)

- Walter Millis, The Martial Spirit: A Study of Our War with Spain (1931)

- H. Wayne Morgan, America's Road to Empire: The War with Spain and Overseas Expansion (1965)

- John L. Offner, An Unwanted War: The Diplomacy of the United States and Spain over Cuba, 1895-1898 (1992).

- Offner, John L. "McKinley and the Spanish-American War" Presidential Studies Quarterly 2004 34(1): 50-61. ISSN 0360-4918

- Pratt, Julius W. The Expansionists of 1898 (1936)

- Schoonover, Thomas. Uncle Sam's War of 1898 and the Origins of Globalization. 2003

- Tone, John Lawrence. War and Genocide in Cuba, 1895-1898 (2006)

The war

- Donald Barr Chidsey, The Spanish American War ( New York, 1971)

- Cirillo, Vincent J. Bullets and Bacilli: The Spanish-American War and Military Medicine 2004.

- Graham A. Cosmas, An Army for Empire: The United States Army and the Spanish-American War (1971)

- Frank Freidel, The Splendid Little War (1958), well illustrated narrative by scholar

- Allan Keller, The Spanish-American War: A Compact History 1969

- Gerald F. Linderman, The Mirror of War: American Society and the Spanish-American War (1974), domestic aspects

- G. J. A. O'Toole, The Spanish War: An American Epic—1898 (1984).

- John Tebbel, America's Great Patriotic War with Spain (1996)

- David F. Trask, The War with Spain in 1898 (1981)

Historiography

- Duvon C. Corbitt, "Cuban Revisionist Interpretations of Cuba's Struggle for Independence," Hispanic American Historical Review 32 (August 1963): 395-404.

- Edward P. Crapol, "Coming to Terms with Empire: The Historiography of Late-Nineteenth-Century American Foreign Relations," Diplomatic History 16 (Fall 1992): 573-97;

- Hugh DeSantis, "The Imperialist Impulse and American Innocence, 1865-1900," in Gerald K. Haines and J. Samuel Walker, eds., American Foreign Relations: A Historiographical Review (1981), pp. 65-90

- James A. Field Jr., "American Imperialism: The Worst Chapter' in Almost Any Book," American Historical Review 83 (June 1978): 644-68, past of the "AHR Forum," with responses

- Joseph A. Fry, "William McKinley and the Coming of the Spanish American War: A Study of the Besmirching and Redemption of an Historical Image," Diplomatic History 3 (Winter 1979): 77-97

- Joseph A. Fry, "From Open Door to World Systems: Economic Interpretations of Late-Nineteenth-Century American Foreign Relations," Pacific Historical Review 65 (May 1996): 277-303

- Thomas G. Paterson, "United States Intervention in Cuba, 1898: Interpretations of the Spanish-American-Cuban-Filipino War," History Teacher 29 (May 1996): 341-61;

- Louis A. Pérez Jr.; The War of 1898: The United States and Cuba in History and Historiography University of North Carolina Press, 1998

- Ephraim K. Smith, "William McKinley's Enduring Legacy: The Historiographical Debate on the Taking of the Philippine Islands," in James C. Bradford, ed., Crucible of Empire: The Spanish-American War and Its Aftermath (1993), pp. 205-49

Memoirs

- Funston, Frederick. Memoirs of Two Wars, Cuba and Philippine Experiences. New York: Charles Schribner's Sons, 1911

- U.S. War Dept. Military Notes on Cuba. 2 vols. Washington, DC: GPO, 1898.

- Wheeler, Joseph. The Santiago Campaign, 1898.Lamson, Wolffe, Boston 1898.

Newspaper and Magazine stories

- Cross, W. American Heritage Magazine. The perils of Evangelina. Feb. 1968.

- Cull, N. J., Culbert, D., Welch, D. Propaganda and Mass Persuasion: A Historical Encyclopedia, 1500 to the Present. Spanish-American War. Denver: ABC-CLIO. 2003. 378-379.

- Daley, L. El Fortin Canosa en la Cuba del 1898. in Los Ultimos Dias del Comienzo. Ensayos sobre la Guerra Hispano-Cubana-Estadounidense. B. E.Aguirre and E. Espina eds. RiL Editores, Santiago de Chile 2000. pp. 161-171.

- Davis, R. H. New York Journal. Does our flag shield women? 13 February 1897.

- Duval, C. New York Journal. Evengelina Cisneros rescued by The Journal. 10 October 1897.

- Kendrick M. New York Journal. Better she died then reach Ceuta. 18 August 1897.

- Kendrick, M. New York Journal. The Cuban girl martyr. 17 February 1897.

- Kendrick, M. New York Journal. Spanish auction off Cuban girls. 12 February 1897.

- McCook, Henry C. The Martial Graves of Our Fallen Heroes in Santiago de Cuba. Philadelphia: Jacobs, 1899.

- Muller y Tejeiro, Jose. Combates y Capitulacion de Santiago de Cuba. Marques, Madrid:1898. 208 p. English translation by US Navy Dept.

- Dirks, Tim. War and Anti-War Films. The Greatest Films. Retrieved November 9, 2005.

- Adjutant General's Office Statistical Exhibit of Strength of Volunteer Forces Called Into Service During the War With Spain; with Losses From All Causes)Washington: Government Printing Office, 1899

Notes

- ↑ McCook (1899 pp. 417-442) who examined each known grave lists each of about 938 dead in his “Index of the Fallen” and mentions 1,415 treated at Siboney Hospital after the battle of San Juan Hill, which would include the numbers killed in the action around fort Canosa (Daley 2000). McCook mentions that very few died of wounds (these are included in the Index) once they reached this hospital. This differs from more official US figures: 385 killed in action 1,662 wounded and 2,061 dead from other causes [1]. Patrick McSherry lists for all theaters 332 combat deaths, 1,641 wounded, other causes of death 2,957, for a total of 3,549 US deaths [2]. Although these figures differ in proportions, the sum of US battle casualties in Cuba are congruent at about 2,200. McSherry lists 21 US Military killed in Philippines and Puerto Rico is about the same approximately 2,000 plus 260 sailors dead in the Maine explosion. The number of Spanish dead in and around Cuba including sailors is hard to estimate: “One century after the war experts still do not a clear idea about the Spanish casualties in the Spanish American War.” McSherry estimates 5,000–6,000 thousand battle losses between 1895 and 1898 in campaigns against Cuban insurgents. Cuban forces, especially Supreme Cuban commander Máximo Gómez deliberately lured the Spanish into known fever areas. In addition it is widely reported that it was financially advantageous for the Spanish military field leadership to underreport casualties. Estimates of Spanish losses to the insurgents in the Philippines were not found; however the war is described as bloody [3], such as in "The Siege of Baler"[4]. See individual battle articles for precise losses for each engagement.

- ↑ Hearst was famously reported (though probably erroneously) to have told artist Frederick Remington: "Please remain. You furnish the pictures and I'll furnish the war."

- ↑ Offner 1992 pp 131-35; Michelle Bray Davis, and Rollin W. Quimby, "Senator Proctor's Cuban Speech: Speculations on a Cause of the Spanish-American War," Quarterly Journal of Speech 1969 55(2): 131-141. ISSN 0033-5630

- ↑ Daley, 2000

- ↑ McCook, 1899

- ↑ Christian de Saint Hubert and Carlos Alfaro Zaforteza, "The Spanish Navy of 1898," Warship International vol. 7 (1980): 39 - 59, 110 - 119.

- ↑ Willard B. Gatewood Jr.; Black Americans and the White Man's Burden, 1898-1903. (1975), p. 23-29; there were some opponents, ibid. p 30-32.

External links

- Centennial of the Spanish-American War 1898–1998 by Lincoln Cushing

- The World of 1898: The Spanish-American War - Library of Congress Hispanic Division

- William Glackens prints at the Library of Congress

- Spanish-American War Centennial

- Images of Florida and the War for Cuban Independence, 1898 from the State Archives of Florida

- Individual state's contributions to the Spanish-American War: Illinois, United States of America Pennsylvania

- Sons of Spanish American War Veterans

- From 'Dagoes' to 'Nervy Spaniards,' American Soldiers' Views of their Opponents, 1898 by Albert Nofi

- History of Negro soldiers in the Spanish-American War, and other items of interest, by Edward Augustus Johnston, published 1899, hosted by the Portal to Texas History.

- The War of 98 (The Spanish-American War) The Spanish-American War from a Spanish perspective (in English).

Template:American conflicts

da:Den spansk-amerikanske krig de:Spanisch-Amerikanischer Krieg es:Guerra Hispano-Estadounidense fr:Guerre hispano-américaine ko:미국-에스파냐 전쟁 id:Perang Spanyol-Amerika it:Guerra ispano-americana he:מלחמת ארצות הברית-ספרד sw:Vita ya Marekani dhidi Hispania nl:Spaans-Amerikaanse Oorlog ja:米西戦争 no:Den spansk-amerikanske krigen nn:Den spansk-amerikanske krig pl:Wojna amerykańsko-hiszpańska pt:Guerra Hispano-Americana ru:Испано-американская война simple:Spanish-American War fi:Espanjan ja Yhdysvaltojen sota sv:Spansk-amerikanska kriget zh:美西战争

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.