Difference between revisions of "Shenandoah National Park" - New World Encyclopedia

(images okay) |

({{Contracted}}) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{Claimed}}{{Images OK}} | + | {{Claimed}}{{Images OK}}{{Contracted}} |

{{otheruses4|the national park in Virginia||Shenandoah}} | {{otheruses4|the national park in Virginia||Shenandoah}} | ||

{{Infobox_protected_area | name = Shenandoah National Park | {{Infobox_protected_area | name = Shenandoah National Park | ||

Revision as of 14:55, 17 October 2007

- This article is about the national park in Virginia. For other uses of the term, see Shenandoah.

| Shenandoah National Park | |

|---|---|

| IUCN Category II (National Park) | |

| | |

| Location: | Virginia, USA |

| Nearest city: | Waynesboro |

| Area: | 199,017 acres (805 km²) |

| Established: | December 26, 1935 |

| Visitation: | 1,076,150 (in 2006) |

| Governing body: | National Park Service |

Shenandoah National Park encompasses part of the Blue Ridge Mountains in the U.S. state of Virginia. This national park is long and narrow, with the broad Shenandoah River and valley on the west side, and the rolling hills of the Virginia Piedmont on the east. Almost 40 % of the land area (79,579 acres/322 km²) has been designated as Wilderness and is protected as part of the National Wilderness Preservation System. The highest peak is Hawksbill Mountain at 4,051 feet (1,235 m).

History

Shenandoah was authorized in 1926 and fully established on December 26, 1935. Prior to being a park, much of the area was farmland and there are still remnants of old farms in several places. The state of Virginia slowly acquired the land by Virginia eminent domain (terms: "condemnation" in US or "compulsory purchase" in UK) laws and procedures[1] from landowners and then gave it to the U.S. Government provided it would be designated a National Park.

In the creation of the park and Skyline Drive, a number of families and entire communities were required to vacate portions of the Blue Ridge Mountains. Many residents in the 500 homes in eight affected counties of Virginia were vehemently opposed to losing their homes and communities. Most of the families removed came from Madison County, Page County, and Rappahannock County.

The development of the park and the construction of Skyline Drive created badly needed jobs for many Virginians during the Great Depression. Nearly 90% of the inhabitants worked the land for a living. Many worked in the apple orchards in the valley and in areas near the eastern slopes. The work to create the National Park and Skyline Drive began following a terrible drought in 1930 which destroyed the crops of many families in the area who farmed in the mountainous terrain, as well as many of the apple orchards where they worked picking crops. Nevertheless, it remains a fact that they were displaced, often against their will, and even for a very few who managed to stay, their communities were lost. A little-known fact is that, while some families were removed by force, a few others (who mostly had also become difficult to deal with) were allowed to stay after their properties were acquired, living in the park until nature took its course and they gradually died. The last to die was Annie Lee Bradley Shenk who died in 1979 at age 92. Most of the people displaced left their homes quietly. According to the Virginia Historical Society, eighty-five-year-old Hezekiah Lam explained, "I ain't so crazy about leavin' these hills but I never believed in bein' ag'in (against) the Government. I signed everythin' they asked me." [1] The lost communities and homes were a price paid for one of the country's most beautiful National Parks and scenic roadways.

In the early 1930s, the National Park Service began planning the park facilities and envisioned separate provisions for "colored guests," as African Americans were described in contemporaneous government documents. At that time, in Jim Crow Virginia, racial segregation was the order of the day. In its transfer of the parkland to the federal government, Virginia initially attempted to ban African Americans entirely from the park, but settled for enforcing its segregation laws in the park's facilities.

By the Thirties, there were several concessions operated by private firms within the park, some going back to the late 19th Century. These early private facilities at Skyland Resort, Panorama Resort, and Swift Run Gap, of course, were operated only for whites. By 1937, the Park Service accepted a bid from Virginia Sky-Line Company to take over the existing facilities and add new lodges, cabins, and other amenities, including Big Meadows Lodge. Under their plan, all the sites in the parks, save one, were for "Whites Only." Their plan included a separate facility for African Americans at Lewis Mountain — a picnic ground, a smaller lodge, cabins and a campground. The site opened in 1939, and it was substantially inferior to the other park facilities. By then, however, the Interior Department was increasingly anxious to eliminate segregation from all parks. Pinnacles picnic ground was selected to be the initial integrated site in the Shenandoah, but Sky-Line continued to balk, and distributed maps showing Lewis Mountain as the only site for African Americans. During World War II, concessions closed and park usage plunged. But once the War ended, in December 1945, the NPS mandated that all concessions in all national parks were to be desegregated. In October 1947 the dining rooms of Lewis Mountain and Panarama were integrated and by early 1950, the mandate was fully accomplished.

Since 1977, nearly half of the Green Springs National Historic Landmark District, a nearby area affiliated with Shenandoah National Park, has been protected by preservation easements held by the National Park Service.

Attractions

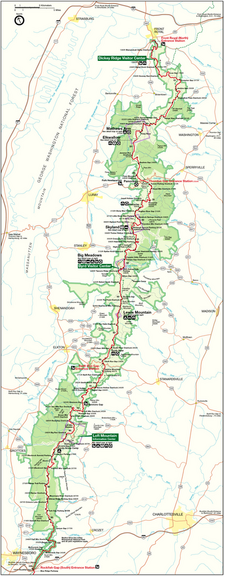

The park is best known for Skyline Drive, a 105 mile (169 km) road that runs the entire length of the park along the ridge of the mountains. The drive is particularly popular in the fall when the leaves are changing colors. 101 miles (162 km) of the Appalachian Trail are also in the park. In total, there are over 500 miles (800 km) of trails within the park. Of the trails, one of the most popular is Old Rag Mountain, which offers a thrilling rock scramble and some of the most breathtaking views in Virginia. There is also horseback riding, camping, bicycling, and many waterfalls. The Skyline Drive is designated as a National Scenic Byway.

Lodges are located at Skyland and Big Meadows. The Park's Harry F. Byrd Visitor Center is also located at Big Meadows. Another visitor center is located at Dickey Ridge. Campgrounds are located at Mathews Arm, Big Meadows, Lewis Mountain, and Loft Mountain.

Rapidan Camp, the restored historic (circa 1931) presidential fishing retreat of Herbert Hoover on the Rapidan River is accessed by a 4.1-mile round-trip hike on Mill Prong Trail, which begins on the Skyline Drive at Milam Gap (Mile 52.8). The NPS also offers guided van trips that leave from the Byrd Center at Big Meadows.

Shenandoah National Park is one of the most dog-friendly in the national park system. The campgrounds all allow dogs, and dogs are allowed on almost all of the trails including the Appalachian Trail, if kept on leash (6-feet or shorter) [2].

Ecology

The climate of the park is typical eastern mid-Atlantic woodland and only the highest points of the mountains show much change or alteration of typical flora and fauna species as might be found at sea level. On southwestern faces of some of the southernmost hillsides pine predominates and there is also the occasional prickly pear cactus which grows naturally. In contrast, some of the northeastern aspects are most likely to have small but dense stands of moisture loving hemlocks and mosses in abundance. Other commonly found plants include oak, hickory, chestnut, maple, tulip poplar, mountain laurel, milkweed, daisies, and many species of ferns. The once predominant American Chestnut tree was effectively brought to extinction by a fungus known as the Chestnut blight during the 1930s – though the tree continues to grow in the park, it does not reach maturity and dies back before it can reproduce. Various species of Oaks superseded the Chestnuts and became the dominant tree species. Gypsy moth infestations beginning in the early 1990s began to erode the dominance of the oak forests as the moths would primarily consume the leaves of oak trees. Though the Gypsy moths seem to have abated some, they continue to affect the forest and have destroyed almost 10 percent of the oak groves.

- Mammals include Whitetailed deer, black bear, bobcat, raccoon, skunk, opossum, groundhog, gray fox, and eastern cottontail rabbit. Though unsubstantiated, there have some reported sightings of mountain lion in remote areas of the park.[citation needed]

- Over 200 species of birds make their home in the park for at least part of the year. About thirty live in the park year round, including barred owls, Carolina chickadees, Red-tailed Hawks, and wild turkeys. The Peregrine Falcon was reintroduced into the park in the mid 1990s and by the end of the 20th century there were numerous nesting pairs in the park.

- Thirty-two species of fish have been documented in the park, including brook trout, longnose and blacknose dance, and the bluehead chub.

Waterfalls

|

File:Rose river falls 20030906 145007 1.jpg Rose River Falls File:Shenandoah - south river falls.jpg South River Falls File:Darkhollow2007.jpg Dark Hollow Falls |

See also

- National parks (United States)

- List of national parks

- Lost counties, cities and towns of Virginia

- Skyland Resort

- Big Meadows

- Hawksbill Mountain

- Old Rag Mountain

Foot Notes

- ↑ http://www.vahistory.org/shenandoah.html#ch3

- ↑ http://www.nps.gov/shen/planyourvisit/pets.htm Official SNP Pet Policy

Sources and Further reading

- Radlauer, Ruth, Ed Radlauer, and Rolf Zillmer. 1982. Shenandoah National Park. Parks for people. Chicago: Childrens Press. ISBN 0516077449 and ISBN 9780516077444

- Manning, Russ, and Russ Manning. 2000. 75 hikes in Virginia's Shenandoah National Park. Seattle, WA: Mountaineers. ISBN 0898866359 and ISBN 9780898866353

- Shelton, Napier. 1975. The nature of Shenandoah: a naturalist's story of a mountain park. [Harpers Ferry, W. Va.]: Office of Publications, National Park Service, U.S. Dept. of the Interior.

- Butcher, Russell D., and Lynn P. Whitaker. 1999. Guide to national parks. Northeast region. NPCA national park guide series. Guilford, Conn: Globe Pequot Press. ISBN 0762705728 and ISBN 9780762705726

- Blackley, Pat, and Chuck Blackley. 2003. Shenandoah National Park impressions. Helena, MT: Farcounty Press. ISBN 1560372303 and ISBN 9781560372301

External links

- National Park Service. Shenandoah. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- National Park Service. When Past is Present : Archaeology of the Displaced in Shenandoah National Park. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- Earth Observatory. Shenandoah National Park. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- Earth Observatory. National Park, Virginia. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

- Virginia is for Lovers. Shenandoah National Park. Retrieved August 17, 2007.

| National parks of the United States | |

|---|---|

| Acadia • American Samoa • Arches • Badlands • Big Bend • Biscayne • Black Canyon of the Gunnison • Bryce Canyon • Canyonlands • Capitol Reef • Carlsbad Caverns • Channel Islands • Congaree • Crater Lake • Cuyahoga Valley • Death Valley • Denali • Dry Tortugas • Everglades • Gates of the Arctic • Glacier • Glacier Bay • Grand Canyon • Grand Teton • Great Basin • Great Sand Dunes • Great Smoky Mountains • Guadalupe Mountains • Haleakala • Hawaii Volcanoes • Hot Springs • Isle Royale • Joshua Tree • Katmai • Kenai Fjords • Kings Canyon • Kobuk Valley • Lake Clark • Lassen Volcanic • Mammoth Cave • Mesa Verde • Mount Rainier • North Cascades • Olympic • Petrified Forest • Redwood • Rocky Mountain • Saguaro • Sequoia • Shenandoah • Theodore Roosevelt • Virgin Islands • Voyageurs • Wind Cave • Wrangell-St. Elias • Yellowstone • Yosemite • Zion List by: date established, state |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.