Smalls, Robert

Lindsay Hull (talk | contribs) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (9 intermediate revisions by 7 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Paid}}{{approved}}{{images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{copyedited}} |

| + | {{epname|Smalls, Robert}} | ||

{{Infobox_Congressman | {{Infobox_Congressman | ||

| name=Robert Smalls | | name=Robert Smalls | ||

| Line 10: | Line 11: | ||

| state=[[South Carolina]] | | state=[[South Carolina]] | ||

| district= [[South Carolina's 5th congressional district|5th]] and [[South Carolina's 7th congressional district|7th]] | | district= [[South Carolina's 5th congressional district|5th]] and [[South Carolina's 7th congressional district|7th]] | ||

| − | | term= March | + | | term= March 1875-March 1879, July 1882-March 1883, and March 1884-March 1887 |

| preceded=[[Richard H. Cain]] | | preceded=[[Richard H. Cain]] | ||

| succeeded=[[William Elliott (South Carolina)|William Elliott]] | | succeeded=[[William Elliott (South Carolina)|William Elliott]] | ||

| party=[[Republican Party (United States)|Republican]] | | party=[[Republican Party (United States)|Republican]] | ||

| spouse=}} | | spouse=}} | ||

| − | '''Robert Smalls''' ([[ | + | '''Robert Smalls''' (April 5, 1839 - February 23, 1915) was a [[mulatto]] [[slavery|slave]] in the [[United States]] who freed himself and his family in May 1862, and subsequently became a naval hero. Awarded a Commission as a captain in the U.S. Navy during the [[American Civil War]] he was the first black man to command a [[United States Navy]] ship. In post-bellum America, he became a [[politician]] serving in [[South Carolina]] State legislature and Senate, then in the 44th, 45th, and 47th to 49th [[United States Congress]]es. Although he had been treated "well" in slavery and had wider latitude and freedom than most bondsmen, he had always longed for escape and took an active part in achieving this for himself and for his family. |

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | His actions as a Navy ship captain helped to bolster support for the entrance of blacks into the military. They also provided evidence of the ability of blacks to perform on an equal level as whites against the conventional wisdom that blacks were best suited for physical labor, but not for anything more intellectually demanding. Smalls dedicated his life to the realization of [[racial equality]] and the fulfillment of [[civil rights]] for the freedmen. In his own day he was a hero for his courage and bravery in struggling for greater freedom for himself and for his fellows. That struggle had a long way to go, and the torch he carried was picked up and carried by people such as [[Martin Luther King, Jr.]] before full Civil Rights were achieved. Despite his opposition to black disenfranchisement, his own State was a pioneer in implementing the [[Jim Crow laws|Jim Crow]] segregation laws. Smalls also faced opposition in his efforts to secure equality for blacks, and at one point was falsely charged with corruption. He prefigured the issue that sparked the [[African-American Civil Rights Movement|Civil Rights Movement]] by famously trying to secure a bill that would give former slaves and blacks equity with whites aboard public [[transportation]] vehicles. Had he succeeded, people such as [[Rosa Parks]] might not have entered [[history]]—at least in the way that they did. Smalls was a [[prophet]]ic voice, proclaiming what was right but what his nation was not then prepared to accept. | ||

==Early life== | ==Early life== | ||

| − | Robert Smalls was born in Beaufort, South Carolina to a house servant named Lydia Smalls and an unknown father (rumored to have been a prominent white man). As a slave, Robert Smalls was owned by John McKee. When he died, Smalls was passed to his son, Henry. Smalls had kind masters, yet he longed for a world free from the cruelties of slavery | + | Robert Smalls was born in Beaufort, [[South Carolina]], to a house servant named Lydia Smalls and an unknown father (rumored to have been a prominent white man). As a slave, Robert Smalls was owned by John McKee. When he died, Smalls was passed to his son, Henry McKee. Smalls had kind masters, yet he longed for a world free from the cruelties of [[slavery]] which surrounded him.<ref>Gerald Henig, "The Unstoppable Mr.Smalls," ''America's Civil War,'' March 2007.</ref> Smalls was hired out by his master and held several jobs in Charleston, South Carolina, and finally began working in the docks. Gradually, he learned seamanship, and then to be a ship's pilot, gaining complete knowledge of the [[Charleston]] harbor. He was married to Hannah Jones, a slave owned by Samuel Kingsman, in 1857, and had a child, named Elizabeth, with her on February 12, 1858.<ref>Dorothy L. Drinkard, "Robert Smalls," in ''Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History,'' eds. David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000), 1804.</ref> |

===Escape from the Confederacy=== | ===Escape from the Confederacy=== | ||

| − | In the fall of 1861, Smalls was made helmsman (though he would have been classified a pilot had he not been a slave) of the ''Planter'' | + | In the fall of 1861, Smalls was made [[helmsman]] (though he would have been classified a pilot had he not been a slave) of the [[CSS Planter|CSS ''Planter,'']] an armed [[Confederacy|Confederate]] [[military transport]]. On May 12, 1862, the ''Planter's'' three white officers were spending the night ashore. Smalls and several other black crew members decided to make a run for Union vessels which were [[blockade\blockading]] Charleston harbor, following a plan which Smalls had devised with them for some time. They made a stop at a nearby ship to pick Smalls' family and other crew's relatives, who had been concealed there for some time.<ref>Drinkard, 1805.</ref> |

| − | On 13 | + | On May 13, 1862, Smalls commandeered the ''Planter.'' With his wife and children, and a small group of other slaves hoping to escape, Smalls made a daring run aboard the ''Planter'' out of Charleston's harbor. Smalls piloted his ship past the five Confederate forts which guarded the harbor, including [[Fort Sumter]]. He knew where the [[mine (aramment)|mine]]s had been placed by Confederates and sailed right past them. He then headed straight for the Federal fleet, which was part of the [[Union blockade]] of Confederate ports, making sure to first hoist a [[surrender|white flag]]. The first ship he encountered was [[USS Onward|USS ''Onward,'']] which prepared to fire until one sailor noticed the white flag. When the Onward's captain boarded the ''Planter,'' Smalls requested to raise the [[United States]] [[flag]] immediately. Smalls turned the ''[[USS Planter (1862)|Planter]]'' over to the [[United States Navy]], along with its onboard cache of [[weapon]]s and [[explosive]]s. |

===Service to the Union=== | ===Service to the Union=== | ||

| + | Because of Smalls' extensive experience in [[shipyard]]s and with the confederate defenses, he was able to provide valuable assistance to the Union. Smalls provided valuable intelligence about the defenses of Charleston harbor to Admiral [[Samuel Dupont]], commander of the Union ships guarding Charleston. | ||

| − | + | Smalls became famous as a hero throughout the North. Several newspapers ran articles describing his actions. Congress passed a bill, signed by President [[Abraham Lincoln]], awarding a financial reward to Smalls and his crew, and awarded him $1,500 for his valor. (The Conferedates, conversely, put a $4,000 bounty on his head.) Smalls' actions became a major point in favor of allowing blacks to fight for the [[Union Army]]. Smalls served under the command of the Navy until transferred to the command of the Army in March 1863. He was never a member of either service. | |

| − | Smalls | + | With the encouragement of Major-General [[David Hunter]], Union commander at Port Royal, Smalls went to [[Washington, D.C.]] to persuade President Lincoln and [[United States Secretary of War|Secretary of War]] [[Edwin Stanton]] to permit blacks to fight for the Union. He was successful, and got an order signed by Stanton permitting 5,000 African-Americans to join the Union forces at [[Port Royal, South Carolina|Port Royal]]. This force became the [[1st South Carolina Volunteers (Union)|1st South Carolina Volunteers]]. |

| − | + | Smalls continued to serve as a pilot for the Union. On April 7, 1863, Smalls piloted [[ironclad]] [[USS Keokuk (1862)|USS ''Keokuk'']] in a Union attack on Fort Sumter. The attack failed, and ''Keokuk'' was badly damaged. The crew was rescued shortly before the ship sank. | |

| − | Smalls | + | Smalls returned to his old ship the ''Planter,'' now a Union transport. In December 1863, after an act of bravery under fire, Smalls became the first black captain of a vessel in the service of the United States. On December 1, 1863, the ''Planter'' was caught in a crossfire from Union and Confederate forces. The ship's commander, Captain Nickerson, ordered the ship to be surrendered. Smalls refused, saying any blacks would not be treated as prisoners of war, but would be killed by the Confederates. Smalls took command and piloted his ship out of the range of the Confederate guns. For that act, he was made a captain, becoming the first black man to command a United States ship. |

| − | + | ===After the war=== | |

| − | + | In 1866, Smalls went into business in Beaufort with [[Richard Howell Gleaves]], opening a store for freedmen (freed slaves). He also began a foray into politics. | |

| − | + | During [[Reconstruction]], Smalls served in the [[South Carolina House of Representatives]] (1865-1870) and in the [[South Carolina Senate]] (1871-1874). He was elected to the [[United States House of Representatives]] and served from 1875-1879 and 1882-1883 in [[South Carolina's 5th congressional district]], and 1884-1887 in [[South Carolina's 7th congressional district]]. Smalls served in the 44th, 45th, and 47th to 49th U.S. Congresses. During consideration of a bill to reduce and restructure the [[United States Army]] he introduced an amendment that included this wording, “Hereafter in the enlistment of men in the Army … no distinction whatsoever shall be made on account of race or color.” The amendment was not considered. He famously tried, as a Congressmen, to secure legislation to give black people the same rights to accommodation on public buses as whites, an issue that many years later, when in 1955 [[Rosa Parks]] refused to yield her seat to a white man, sparked the [[African-American Civil Rights Movement]]. | |

| − | + | In 1877, after the [[Compromise of 1877]], and as a part of wide ranging white efforts to mute African American political power and rights, Smalls was charged and convicted of taking a bribe five years earlier, in 1872, in connection with the awarding of a printing contract. He was pardoned as part of a deal in which charges were also dropped against [[Democratic Party (United States)|Democrats]] accused of election fraud.<ref>Eric Foner, ed., ''Freedom's Lawmakers: A Directory of Black Officeholders During Reconstruction'' (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1996), 198.</ref> | |

| − | + | Smalls remained a political figure into the twentieth century and was a delegate to the 1895 South Carolina constitutional convention. He spoke out against the disenfranchisement of black voters in a famous speech, but the State went ahead with its [[Jim Crow laws]] led by the white supremacist, Senator Tillman, circumventing the 15th Amendment of the [[United States Constitution]]. With one break in service, Smalls was U.S. Collector of Customs 1889–1911 in Beaufort, S.C., where he lived as owner in the house in which he had been a slave. The Robert Smalls house is now a [[National Historic Landmark]]. Small's first wife died in 1883, after bearing three children, Elizabeth, Robert, Jr. (who was born in 1861 and died at age three), and Sarah (born December 1, 1863). In 1890 or 1891, he remarried to [[Annie Wigg]], a teacher, and the couple went on to have one child, William Robert, born in 1892.<ref>Drinkard, 1806.</ref> The desk that Smalls used as Collector of Customs is on display at the Beaufort Arsenal Museum in Beaufort. In 2004, a ship was launched which is named for Robert Smalls. It is LSV-8, a [[Logistics Support Vessel]] which is operated by the [[U.S. Army]]. | |

| − | + | He is buried with his family in downtown Beaufort, where there is a monument and a sculpture dedicated to his memory. | |

| − | |||

| − | He is buried with his family in downtown Beaufort where there is a monument and a sculpture dedicated to his memory. | ||

==Legacy== | ==Legacy== | ||

| − | Robert Smalls, though treated "well" | + | Robert Smalls, though treated "well" as a slave and given wider latitude and freedom than most bondsmen, longed for an escape from the institution of slavery and took active part in achieving this for himself and his family. His actions as a pilot helped to bolster support for the entrance of blacks into the military. They also provided evidence of the ability of former slaves to perform on an equal level. A popular, if not conventional, view at the time was that blacks were born inherently inferior to whites and were thus naturally accustomed for servitude. Smalls dedicated his life to the realization of racial equality and the fulfillment of rights for the freedmen. Robert Smalls became a hero in his day for the bravery he exhibited in his struggle for greater freedom and recognition. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| Line 61: | Line 60: | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | * Drinkard, Dorothy L. "Robert Smalls." In ''Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History'' | + | * Drinkard, Dorothy L. "Robert Smalls." In ''Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History,'' edited by David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler, 1804-1806. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000. ISBN 0-393-04758-X |

| − | * | + | * Foner, Eric, ed. ''Freedom's Lawmakers: A Directory of Black Officeholders During Reconstruction''. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1996. ISBN 0-8071-2082-0 |

* Henig, Gerald. "The Unstoppable Mr.Smalls." ''America's Civil War'', March 2007. | * Henig, Gerald. "The Unstoppable Mr.Smalls." ''America's Civil War'', March 2007. | ||

* Rabinowitz, Howard N. ''Southern Black Leaders of the Reconstruction Era''. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1982. ISBN 0-252-00929-0 | * Rabinowitz, Howard N. ''Southern Black Leaders of the Reconstruction Era''. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1982. ISBN 0-252-00929-0 | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | {{congbio|S000502}} | + | All links retrieved December 15, 2022. |

| − | + | {{congbio|S000502}} | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | [[Category:Politicians and reformers]] | |

| − | |||

[[Category:History]] | [[Category:History]] | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Credits|167635610}} |

Latest revision as of 02:16, 16 December 2022

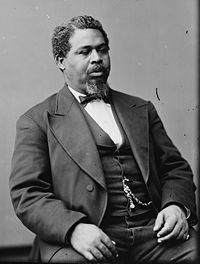

Robert Smalls (April 5, 1839 - February 23, 1915) was a mulatto slave in the United States who freed himself and his family in May 1862, and subsequently became a naval hero. Awarded a Commission as a captain in the U.S. Navy during the American Civil War he was the first black man to command a United States Navy ship. In post-bellum America, he became a politician serving in South Carolina State legislature and Senate, then in the 44th, 45th, and 47th to 49th United States Congresses. Although he had been treated "well" in slavery and had wider latitude and freedom than most bondsmen, he had always longed for escape and took an active part in achieving this for himself and for his family.

His actions as a Navy ship captain helped to bolster support for the entrance of blacks into the military. They also provided evidence of the ability of blacks to perform on an equal level as whites against the conventional wisdom that blacks were best suited for physical labor, but not for anything more intellectually demanding. Smalls dedicated his life to the realization of racial equality and the fulfillment of civil rights for the freedmen. In his own day he was a hero for his courage and bravery in struggling for greater freedom for himself and for his fellows. That struggle had a long way to go, and the torch he carried was picked up and carried by people such as Martin Luther King, Jr. before full Civil Rights were achieved. Despite his opposition to black disenfranchisement, his own State was a pioneer in implementing the Jim Crow segregation laws. Smalls also faced opposition in his efforts to secure equality for blacks, and at one point was falsely charged with corruption. He prefigured the issue that sparked the Civil Rights Movement by famously trying to secure a bill that would give former slaves and blacks equity with whites aboard public transportation vehicles. Had he succeeded, people such as Rosa Parks might not have entered history—at least in the way that they did. Smalls was a prophetic voice, proclaiming what was right but what his nation was not then prepared to accept.

Early life

Robert Smalls was born in Beaufort, South Carolina, to a house servant named Lydia Smalls and an unknown father (rumored to have been a prominent white man). As a slave, Robert Smalls was owned by John McKee. When he died, Smalls was passed to his son, Henry McKee. Smalls had kind masters, yet he longed for a world free from the cruelties of slavery which surrounded him.[1] Smalls was hired out by his master and held several jobs in Charleston, South Carolina, and finally began working in the docks. Gradually, he learned seamanship, and then to be a ship's pilot, gaining complete knowledge of the Charleston harbor. He was married to Hannah Jones, a slave owned by Samuel Kingsman, in 1857, and had a child, named Elizabeth, with her on February 12, 1858.[2]

Escape from the Confederacy

In the fall of 1861, Smalls was made helmsman (though he would have been classified a pilot had he not been a slave) of the CSS Planter, an armed Confederate military transport. On May 12, 1862, the Planter's three white officers were spending the night ashore. Smalls and several other black crew members decided to make a run for Union vessels which were blockade\blockading Charleston harbor, following a plan which Smalls had devised with them for some time. They made a stop at a nearby ship to pick Smalls' family and other crew's relatives, who had been concealed there for some time.[3]

On May 13, 1862, Smalls commandeered the Planter. With his wife and children, and a small group of other slaves hoping to escape, Smalls made a daring run aboard the Planter out of Charleston's harbor. Smalls piloted his ship past the five Confederate forts which guarded the harbor, including Fort Sumter. He knew where the mines had been placed by Confederates and sailed right past them. He then headed straight for the Federal fleet, which was part of the Union blockade of Confederate ports, making sure to first hoist a white flag. The first ship he encountered was USS Onward, which prepared to fire until one sailor noticed the white flag. When the Onward's captain boarded the Planter, Smalls requested to raise the United States flag immediately. Smalls turned the Planter over to the United States Navy, along with its onboard cache of weapons and explosives.

Service to the Union

Because of Smalls' extensive experience in shipyards and with the confederate defenses, he was able to provide valuable assistance to the Union. Smalls provided valuable intelligence about the defenses of Charleston harbor to Admiral Samuel Dupont, commander of the Union ships guarding Charleston.

Smalls became famous as a hero throughout the North. Several newspapers ran articles describing his actions. Congress passed a bill, signed by President Abraham Lincoln, awarding a financial reward to Smalls and his crew, and awarded him $1,500 for his valor. (The Conferedates, conversely, put a $4,000 bounty on his head.) Smalls' actions became a major point in favor of allowing blacks to fight for the Union Army. Smalls served under the command of the Navy until transferred to the command of the Army in March 1863. He was never a member of either service.

With the encouragement of Major-General David Hunter, Union commander at Port Royal, Smalls went to Washington, D.C. to persuade President Lincoln and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton to permit blacks to fight for the Union. He was successful, and got an order signed by Stanton permitting 5,000 African-Americans to join the Union forces at Port Royal. This force became the 1st South Carolina Volunteers.

Smalls continued to serve as a pilot for the Union. On April 7, 1863, Smalls piloted ironclad USS Keokuk in a Union attack on Fort Sumter. The attack failed, and Keokuk was badly damaged. The crew was rescued shortly before the ship sank.

Smalls returned to his old ship the Planter, now a Union transport. In December 1863, after an act of bravery under fire, Smalls became the first black captain of a vessel in the service of the United States. On December 1, 1863, the Planter was caught in a crossfire from Union and Confederate forces. The ship's commander, Captain Nickerson, ordered the ship to be surrendered. Smalls refused, saying any blacks would not be treated as prisoners of war, but would be killed by the Confederates. Smalls took command and piloted his ship out of the range of the Confederate guns. For that act, he was made a captain, becoming the first black man to command a United States ship.

After the war

In 1866, Smalls went into business in Beaufort with Richard Howell Gleaves, opening a store for freedmen (freed slaves). He also began a foray into politics.

During Reconstruction, Smalls served in the South Carolina House of Representatives (1865-1870) and in the South Carolina Senate (1871-1874). He was elected to the United States House of Representatives and served from 1875-1879 and 1882-1883 in South Carolina's 5th congressional district, and 1884-1887 in South Carolina's 7th congressional district. Smalls served in the 44th, 45th, and 47th to 49th U.S. Congresses. During consideration of a bill to reduce and restructure the United States Army he introduced an amendment that included this wording, “Hereafter in the enlistment of men in the Army … no distinction whatsoever shall be made on account of race or color.” The amendment was not considered. He famously tried, as a Congressmen, to secure legislation to give black people the same rights to accommodation on public buses as whites, an issue that many years later, when in 1955 Rosa Parks refused to yield her seat to a white man, sparked the African-American Civil Rights Movement.

In 1877, after the Compromise of 1877, and as a part of wide ranging white efforts to mute African American political power and rights, Smalls was charged and convicted of taking a bribe five years earlier, in 1872, in connection with the awarding of a printing contract. He was pardoned as part of a deal in which charges were also dropped against Democrats accused of election fraud.[4]

Smalls remained a political figure into the twentieth century and was a delegate to the 1895 South Carolina constitutional convention. He spoke out against the disenfranchisement of black voters in a famous speech, but the State went ahead with its Jim Crow laws led by the white supremacist, Senator Tillman, circumventing the 15th Amendment of the United States Constitution. With one break in service, Smalls was U.S. Collector of Customs 1889–1911 in Beaufort, S.C., where he lived as owner in the house in which he had been a slave. The Robert Smalls house is now a National Historic Landmark. Small's first wife died in 1883, after bearing three children, Elizabeth, Robert, Jr. (who was born in 1861 and died at age three), and Sarah (born December 1, 1863). In 1890 or 1891, he remarried to Annie Wigg, a teacher, and the couple went on to have one child, William Robert, born in 1892.[5] The desk that Smalls used as Collector of Customs is on display at the Beaufort Arsenal Museum in Beaufort. In 2004, a ship was launched which is named for Robert Smalls. It is LSV-8, a Logistics Support Vessel which is operated by the U.S. Army.

He is buried with his family in downtown Beaufort, where there is a monument and a sculpture dedicated to his memory.

Legacy

Robert Smalls, though treated "well" as a slave and given wider latitude and freedom than most bondsmen, longed for an escape from the institution of slavery and took active part in achieving this for himself and his family. His actions as a pilot helped to bolster support for the entrance of blacks into the military. They also provided evidence of the ability of former slaves to perform on an equal level. A popular, if not conventional, view at the time was that blacks were born inherently inferior to whites and were thus naturally accustomed for servitude. Smalls dedicated his life to the realization of racial equality and the fulfillment of rights for the freedmen. Robert Smalls became a hero in his day for the bravery he exhibited in his struggle for greater freedom and recognition.

Notes

- ↑ Gerald Henig, "The Unstoppable Mr.Smalls," America's Civil War, March 2007.

- ↑ Dorothy L. Drinkard, "Robert Smalls," in Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History, eds. David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000), 1804.

- ↑ Drinkard, 1805.

- ↑ Eric Foner, ed., Freedom's Lawmakers: A Directory of Black Officeholders During Reconstruction (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1996), 198.

- ↑ Drinkard, 1806.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Drinkard, Dorothy L. "Robert Smalls." In Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History, edited by David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler, 1804-1806. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000. ISBN 0-393-04758-X

- Foner, Eric, ed. Freedom's Lawmakers: A Directory of Black Officeholders During Reconstruction. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1996. ISBN 0-8071-2082-0

- Henig, Gerald. "The Unstoppable Mr.Smalls." America's Civil War, March 2007.

- Rabinowitz, Howard N. Southern Black Leaders of the Reconstruction Era. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1982. ISBN 0-252-00929-0

External links

All links retrieved December 15, 2022.

- Robert Smalls at the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.