Jim Crow laws

Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enacted in the Southern and border states of the United States after 1876 requiring the separation of African-Americans from white Americans in public facilities, such as public schools, hotels, water fountains, restaurants, libraries, buses, and trains, as well as the legal restrictions placed on blacks from exercising their right to vote.

The term Jim Crow comes from the minstrel show song "Jump Jim Crow" written in 1828 and performed by Thomas Dartmouth "Daddy" Rice, a white English migrant to the U.S. and the first popularizer of blackface performance, which became an immediate success. A caricature of a shabbily dressed rural black named "Jim Crow" became a standard character in minstrel shows. By 1837, Jim Crow was also used to refer to racial segregation generally.

It was not until 1954 in Brown v. Board of Education and 1964, with the enactment of that year's Civil Rights Act, that these discriminatory laws were finally made illegal. Until the "Jim Crow" regime was dismantled, it contributed to a great migration of African Americans to other parts of the United States.

History

At the conclusion of the American Civil War in 1865, and lasting until 1876, in the period of Reconstruction, the federal government took an affirmative and aggressive stance in enacting new federal laws that provided civil rights protection for African-Americans who had formerly been slaves. Among these new laws were the Civil Rights Act of 1866, the Civil Rights Act of 1875, and the fourteenth and fifteenth Amendments to the US Constitution. These enactments guaranteed that everyone, regardless of race, color, or previous condition of servitude, was entitled to the equal use of public accommodation facilities, which included inns, hotels, motels, public transportation such as buses and railway cars, theaters, and other places of public amusement.

After the Civil War, many southern states came under the control of the new Republican Party, which was largely made up of freed black slaves, "Scalawags," and "Carpetbaggers." The Scalawags were white Southerners who joined the Republican Party during the Reconstruction period, interested in re-building the South by ending the power of the plantation aristocracy that had been largely responsible for slavery. The Carpetbaggers were northerners that had moved from the North to the South during this period of Reconstruction.

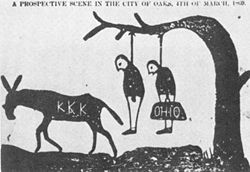

However, many Southerners, particularly members of the Ku Klux Klan, founded by veterans of the Confederate Army, violently resisted this new Republican coalition, as well as the new federal civil rights laws that gave blacks legal rights they never had before. President Ulysses S. Grant was eventually forced to use federal troops to curtail violence against blacks by the Klan, and to use the federal court system to enforce the new federal laws against the Klan.

Meanwhile, Southern Democrats alleged that the Scalawags were financially and politically corrupt, willing to support bad government because they profited personally. By 1877 Southern whites who were opposed to the policies of the Federal government formed their own political coalition to oust the Republicans who were trying to seize control over state and local politics. Known as the ‚ÄúRedeemers,‚ÄĚ these Southerners were a political coalition of conservative and pro-business whites that came to dominate the Democratic Party in the South. They rose to power by being able to reverse many of the civil rights gains that blacks had made during the Reconstruction era, passing laws that virtually mandated discrimination by local governments and private parties.

Starting in 1883, the U.S. Supreme Court started to invalidate some of these congressional enactments. The first to be challenged was the Civil Rights Act of 1875. The Act was found unconstitutional on the basis that it regulated the actions of private companies rather than actions of state governments. The court also held that the fourteenth Amendment only prohibited discrimination by the state, not individuals or corporations; and therefore, most of the provisions of the Civil Rights Act of 1875 were held to be unconstitutional.

One of the most racist of these laws came in the 1890s with the adoption of legislation that mandated the segregation of blacks and whites on railroad cars in New Orleans. Between 1890 and 1910, many state governments prevented most blacks from voting in local and federal elections, using various techniques, such as poll taxes and literacy tests. These new requirements could be waived for whites due to "grandfather clauses," but not for blacks. It is estimated that of 181,000 Black males of voting age in Alabama in 1900, only 3,000 were registered to vote, largely because of Jim Crow laws.

Separate but equal

In "Plessy v. Ferguson" (1896) the Supreme Court held that Jim Crow type laws were constitutional as long as they allowed "separate but equal" facilities. The “separate but equal" requirement eventually led to widespread racial discrimination.

The background of this case is as follows: In 1890, the State of Louisiana passed a law requiring separate accommodations for black and white passengers on railroads. A group of black and white citizens in New Orleans formed an association for the purpose of repealing this new law. They persuaded Homer Plessy, a man with light skin who was one-eighth African, to challenge the law. In 1892 Plessy purchased a first-class ticket from New Orleans on the East Louisiana Railway. When he had boarded the train, he informed the conductor of his racial lineage, but insisted on sitting in the whites-only section. Plessy was asked to leave the railway car that had been designated for white passengers and to sit in the "blacks only" car. Plessy refused to do so, and was later arrested and convicted for not sitting in the railway car designated only for blacks. This case was then appealed to the US Supreme Court.

Writing for the Court, Justice Henry Billings Brown wrote, "We consider the underlying fallacy of the plaintiff's argument to consist in the assumption that the enforced separation of the two races stamps the colored race with a badge of inferiority. If this be so, it is not by reason of anything found in the act, but solely because the colored race chooses to put that construction upon it." Justice John Harlan, a former slave owner, who experienced a conversion as a result of Ku Klux Klan excesses, wrote a scathing dissent, saying that the Court's majority decision would become as infamous as that of the Dred Scott case. Harlan also wrote that in the eyes of the law in this country, there is no superior, or dominant, ruling class of citizens, that the Constitution is color-blind, and does not tolerate classes among citizens.

As an aftermath of this decision, the legal foundation for the doctrine of "separate but equal" was firmly in place. By 1915, every Southern state had effectively destroyed the gains that blacks had obtained through various laws passed by the Federal government during the Reconstruction period. The new restrictions against blacks were eventually extended to the federal government while Woodrow Wilson was President of the US. During his first term in office, the House passed a law making racial intermarriage a felony in the District of Columbia. His new Postmaster General ordered that his Washington, DC offices be segregated, and in time the Department of Treasury did the same. To enable identification a person's race, photographs were required of all applicants for federal jobs.

Examples of Jim Crow laws

The following are examples of Jim Crow laws: [1]

ALABAMA

- Nurses. No person or corporation shall require any white female nurse to work in wards or rooms in hospitals, either public or private, in which Negro men are placed.

- Buses. All passenger stations in this state operated by any motor transportation company shall have separate waiting rooms or space and separate ticket windows for the white and colored races.

- Railroads. The conductor of each passenger train is authorized and required to assign each passenger to the car or the division of the car, when it is divided by a partition, designated for the race to which such passenger belongs.

- Restaurants. It shall be unlawful to conduct a restaurant or other place for the serving of food in the city, at which white and colored people are served in the same room, unless such white and colored persons are effectually separated by a solid partition extending from the floor upward to a distance of seven feet or higher, and unless a separate entrance from the street is provided for each compartment.

FLORIDA

- Intermarriage. All marriages between a white person and a Negro, or between a white person and a person of Negro descent to the fourth generation inclusive, are hereby forever prohibited.

- Cohabitation. Any Negro man and white woman, or any white man and Negro woman, who are not married to each other, who shall habitually live in and occupy in the nighttime the same room shall each be punished by imprisonment not exceeding twelve (12) months, or by fine not exceeding five hundred ($500.00) dollars.

- Education. The schools for white children and the schools for Negro children shall be conducted separately.

LOUISIANA

- Housing. Any person...who shall rent any part of any such building to a Negro person or a Negro family when such building is already in whole or in part in occupancy by a white person or white family, or vice versa when the building is in occupancy by a Negro person or Negro family, shall be guilty of a misdemeanor and on conviction thereof shall be punished by a fine of not less than twenty-five ($25.00) nor more than one hundred ($100.00) dollars or be imprisoned not less than 10, or more than 60 days, or both such fine and imprisonment in the discretion of the court.

MISSISSIPPI

- Promotion of Equality. Any person...who shall be guilty of printing, publishing or circulating printed, typewritten or written matter urging or presenting for public acceptance or general information, arguments or suggestions in favor of social equality or of intermarriage between whites and Negroes, shall be guilty of a misdemeanor and subject to fine or not exceeding five hundred (500.00) dollars or imprisonment not exceeding six (6) months or both.

NORTH CAROLINA

- Textbooks. Books shall not be interchangeable between the white and colored schools, but shall continue to be used by the race first using them.

- Libraries. The state librarian is directed to fit up and maintain a separate place for the use of the colored people who may come to the library for the purpose of reading books or periodicals.

VIRGINIA

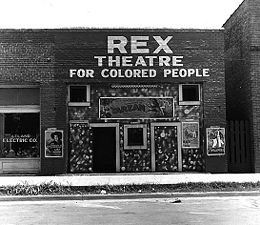

- Theaters. Every person … operating … any public hall, theater, opera house, motion picture show or any place of public entertainment or public assemblage which is attended by both white and colored persons, shall separate the white race and the colored race and shall set apart and designate … certain seats therein to be occupied by white persons and a portion thereof, or certain seats therein, to be occupied by colored persons.

- Railroads. The conductors or managers on all such railroads shall have power, and are hereby required, to assign to each white or colored passenger his or her respective car, coach or compartment. If the passenger fails to disclose his race, the conductor and managers, acting in good faith, shall be the sole judges of his race.

WYOMING

- Intermarriage. All marriages of white persons with Negroes, Mulattos, Mongolians, or Malaya hereafter contracted in the State of Wyoming are and shall be illegal and void.

Jim Crow laws were a product of the solidly Democratic South, that was not able to accept black-Americans as being equal to white-Americans. As the party which supported the Confederacy, the Democratic Party quickly dominated all aspects of local, state, and federal political life in the post-Civil War South.

Twentieth century

Legal milestones

Starting in 1915, on the basis of constitutional law, the Supreme Court began to issue decisions that overturned several Jim Crow laws. In Guinn v. United States 238 US 347 (1915), the Court held that an Oklahoma law that had denied the right to vote to black citizens was unconstitutional. In Buchanan v. Warley 245 US 60 (1917), the Court held that a Kentucky law could not require residential segregation. In 1946, the Court outlawed the white primary election in Smith v. Allwright 321 US 649 (1944), and also in 1946, in Irene Morgan v. Virginia 328 U.S. 373, the high Court ruled that segregation in interstate transportation was unconstitutional. In Shelley v. Kraemer 334 US 1 (1948), the Court held that "restrictive covenants" that barred the sale of homes to blacks, Jews, or Asians, were unconstitutional. This case affected other forms of privately created Jim Crow arrangements, which barred African American from buying homes in certain neighborhoods, from shopping or working in certain stores, from working at certain trades, etc.

Finally, in 1954, in Brown v. Board of Education 347 US 483, the Court held that separate facilities were inherently unequal in the area of public schools. This case overturned Plessy v. Ferguson and eventually had the effect of outlawing Jim Crow in other areas of society as well. However, the Courts ruling was not well received by many Southern Democrats, who in a Congressional resolution in 1956 called the Southern Manifesto, condemned the Supreme Court's ruling. The Manifesto was signed by 19 Senators and 77 House members.

Later, in "Loving v. Virginia," 388 U.S. 1 (1967), another landmark civil rights case, the Supreme Court declared Virginia's anti-"miscegenation" statute, the "Racial Integrity Act of 1924," unconstitutional, thereby overturning Pace v. Alabama (1883) and ending all race-based legal restrictions on marriage in the United States

Civil rights movement

As African-American entertainers, musicians, and literary figures gradually were able to break into the white dominated world of American art and culture after 1890, African-American athletes found obstacles. By 1900, white opposition to African-American boxers, baseball players, track athletes, and basketball players kept them segregated and limited in what they could do. However, their athletic abilities in all-African-American teams and sporting events could not be denied, and one by one the barriers to African-American participation in all the major sports began to crumble, especially after the conclusion of World War II, as many African Americans who had served in the military refused to put up with segregation any longer.

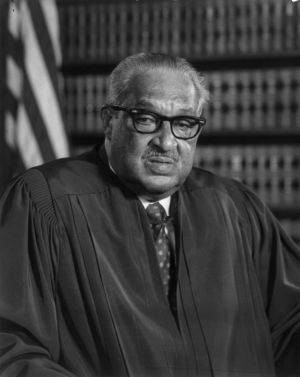

As a result, a new movement began to seek redress through the federal courts. It started with the establishment of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Its lead attorney, Thurgood Marshall, brought the landmark case, Brown v. Board of Education. Marshall was later to become a U.S. Supreme Court Justice.

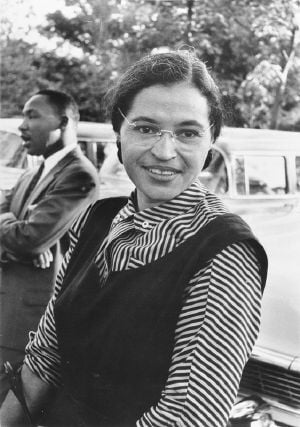

Although attitudes turned against segregation in the federal courts after World War II, the segregationist governments of many Southern states countered with numerous and strict segregation laws. A major challenge to such laws arose when Rosa Parks, on December 1, 1955, an African-American woman in Montgomery, Alabama, refused to give up her seat on a bus to a white man. This was the start of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, which became one of the largest movements against racial segregation, and brought Martin Luther King, Jr. into prominence in the civil rights movement. Subsequent demonstrations and boycotts led to a series of legislation and court decisions in which Jim Crow laws were eventually repealed or annulled.

In Little Rock, Arkansas, a crisis erupted in 1957, when the Governor of Arkansas, Orval Faubus called out the Arkansas National Guard to prevent nine African-American students who had sued for the right to attend an integrated school from attending Little Rock Central High School. Faubus had received significant pressure and came out against integration and against the federal court order that required it. President Dwight D. Eisenhower federalized the Arkansas National Guard and ordered them to their barracks. At the same time, he deployed elements of the 101st Airborne Division to Little Rock to protect the students. The students were able to attend high school, but in the end, the Little Rock school system made the decision to shut down rather than continue to integrate. Other schools across the South did the same.

In early January, 1964, President Lyndon Johnson met with civil rights leaders and during his first State of the Union address shortly thereafter, he asked Congress to "let this session of Congress be known as the session which did more for civil rights than the last hundred sessions combined." In 1964, Congress attacked the parallel system of private Jim Crow practices, and invoking the commerce clause of the Constitution, it passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which outlawed discrimination in public accommodations, i.e., privately owned restaurants, hotels, and stores, and in private schools and workplaces.

On June 21, 1964, civil rights workers Michael Schwerner, Andrew Goodman, and James Chaney, disappeared in Neshoba County, Mississippi. They were later found by the FBI to have been murdered. These three individuals were student-volunteers who traveled to Mississippi to aid in the registration of African-American voters. A deputy sheriff and 16 others individuals, all Ku Klux Klan members, were indicted for the killing of these three civil rights workers. Seven were convicted. On July 2, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Legacy

Although it would not be until 1967 that laws against interracial marriage were overturned, the death knell for Jim Crow laws was sounded by the signing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. As a result, Jim Crow laws are no longer a part of American society. Many African Americans, as well as members of other racial and ethnic groups, have achieved success through opportunities that their parents and grandparents never had. However, despite such progress, vestiges of Jim Crow still remain, and African Americans have yet to totally liberate themselves from the emotional, psychological, and economic damage brought about by the institutions of slavery, Jim Crow laws, and other forms of racial discrimination.

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ Examples of Jim Crow laws. The Jackson Sun. Retrieved July 2, 2015.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ayers, Edward L. The Promise of the New South. Oxford University Press, 1992, ISBN 0195326881

- Barnes, Catherine A. Journey from Jim Crow: The Desegregation of Southern Transit. Columbia University Press, 1983, ISBN 0231053800

- Bartley, Numan V. The Rise of Massive Resistance: Race and Politics in the South during the 1950s. Louisiana State University Press, 1969. ISBN 0807124192

- Dailey, Jane, Glenda Elizabeth Gilmore, and Bryant Simon, eds. Jumpin' Jim Crow: Southern Politics from Civil War to Civil Rights. Princeton University Press, 2000. ISBN 0691001936

- Fairclough, Adam. ‚ÄúBeing in the Field of Education and Also Being a Negro Seems Tragic: Black Teachers in the Jim Crow South," Journal of American History 87 (June 2000): 65‚Äď91.

- Feldman, Glenn. Politics, Society, and the Klan in Alabama, 1915‚Äď1949. University of Alabama Press, 1999. ISBN 0817309845

- Fireside, Harvey, Separate and Unequal: Homer Plessy and the Supreme Court Decision That Legalized Racism. Carroll & Graf, 2004. ISBN 0786712937

- Foner, Eric. Reconstruction, America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877: and 1863-1877. Harpercollins, 1988. ISBN 0060158514

- Gaines, Kevin. Uplifting the Race: Black Leadership, Politics, and Culture in the Twentieth Century. University of North Carolina Press, 1996. ISBN 0807845434

- Gaston, Paul M. The New South Creed: A Study in Southern Mythmaking. Alfred A. Knopf, 1970. ISBN 0807102563

- Gilmore, Glenda Elizabeth. Gender and Jim Crow: Women and the Politics of White Supremacy in North Carolina, 1896-1920. The University of North Carolina Press, 1996. ISBN 0807845965

- Griffin, John Howard Black Like Me. Signet, 1996. ISBN 0451192036

- Hackney, Sheldon. Populism to Progressivism in Alabama. ACLS History E-Book Project, 2001. ISBN 1597401730

- Haws, Robert (ed.). The Age of Segregation: Race Relations in the South, 1890‚Äď1945. University Press of Mississippi, 1978. ISBN 0878050876

- Johnson, Charles S. Patterns of Negro Segregation. Thomas V. Crowell, 1970. ASIN BOOONPHYHY

- Kantrowitz, Stephen. Ben Tillman & the Reconstruction of White Supremacy. The University of North Carolina Press, 2000. ISBN 0807848395

- Klarman, Michael J. From Jim Crow to Civil Rights: The Supreme Court and the Struggle for Racial Equality. Oxford University Press, 2006. ISBN 0195310187

- Litwack, Leon F. Trouble in Mind: Black Southerners in the Age of Jim Crow. Vintage, 1999. ISBN 0375702636 (This is the most complete and moving account we have had of what the victims of the Jim Crow South suffered and somehow endured"‚ÄĒC. Vann Woodward.)

- McMillen, Neil R. Dark Journey: Black Mississippians in the Age of Jim Crow. University of Illinois Press, 1989. ISBN 025206156X

- Medley, Keith Weldon. We As Freemen: Plessy v. Ferguson. Pelican Publishing Company, 2003. ISBN 1589801202.

- Myrdal, Gunnar. An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy. Transaction Publisher, 1996. ISBN 1560008571

- Percy, William Alexander. Lanterns on the Levee: Recollections of a Planter's Son. Louisiana State University Press, 1993. ISBN 0807100722

- Rabinowitz, Howard N. Race Relations in the Urban South, 1856‚Äď1890. University of Georgia Press; New edition, 1996. ISBN 0820318809

- Smith, J. Douglas. Managing White Supremacy: Race, Politics, and Citizenship in Jim Crow Virginia. University of North Carolina Press, 2002. ISBN 0807854247

- Smith, J. Douglas. ‚ÄúThe Campaign for Racial Purity and the Erosion of Paternalism in Virginia, 1922‚Äď1930: 'Nominally White, Biologically Mixed, and Legally Negro.‚Äô‚ÄĚ Journal of Southern History 68 (February 2002): 65‚Äď106.

- Smith, J. Douglas. ‚ÄúPatrolling the Boundaries of Race: Motion Picture Censorship and Jim Crow in Virginia, 1922‚Äď1932.‚ÄĚ Historical Journal of Film, Radio, and Television 21 (August 2001): 273‚Äď91.

- Sterner, Richard. The Negro's Share. ACLS History E-Book Project, 2006. ISBN 1597402753

- Woodward, C. Vann. The Strange Career of Jim Crow. Oxford University Press, 1955. ISBN 0195146905

- Woodward, C. Vann. The Origins of the New South: 1877-1913. Louisiana State University Press, 1976. ISBN 0807100196

External links

All links retrieved January 2, 2025.

- Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia

- An article on "New Racist Forms: Jim Crow in the 21st Century". www.ferris.edu.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.