Difference between revisions of "Pythagoras and Pythagoreans" - New World Encyclopedia

Keisuke Noda (talk | contribs) m |

Keisuke Noda (talk | contribs) m (importing image) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{cleanup-priority}} | {{cleanup-priority}} | ||

| − | + | [[Image:Pythagoras_von_Samos.png|right]] | |

'''Pythagoras''' ([[580s B.C.E.|582 B.C.E.]] – [[496 B.C.E.]], [[Greek language|Greek]]: | '''Pythagoras''' ([[580s B.C.E.|582 B.C.E.]] – [[496 B.C.E.]], [[Greek language|Greek]]: | ||

Πυθαγόρας) was an [[Ionians|Ionian]] [[mathematician]] and [[philosopher]], known best for formulating the [[Pythagorean theorem]]. | Πυθαγόρας) was an [[Ionians|Ionian]] [[mathematician]] and [[philosopher]], known best for formulating the [[Pythagorean theorem]]. | ||

| − | |||

Known as "[[List of people known as the father or mother of something|the father of numbers]]", he made influential contributions to [[philosophy]] and religious teaching in the late [[6th century B.C.E.]]. Because legend and obfuscation cloud his work even more than with the other [[pre-Socratic]]s, one can say little with confidence about his life and teachings. Pythagoras and his students believed that everything was related to [[mathematics]], and felt that everything could be predicted and measured in rhythmic [[cycles]]. | Known as "[[List of people known as the father or mother of something|the father of numbers]]", he made influential contributions to [[philosophy]] and religious teaching in the late [[6th century B.C.E.]]. Because legend and obfuscation cloud his work even more than with the other [[pre-Socratic]]s, one can say little with confidence about his life and teachings. Pythagoras and his students believed that everything was related to [[mathematics]], and felt that everything could be predicted and measured in rhythmic [[cycles]]. | ||

| Line 39: | Line 36: | ||

Some consider Pythagoras the pupil of [[Anaximander]] and some ancient sources tell of his visiting, in his twenties, the philosopher [[Thales]], just before the death of the latter. No account exists of the specifics of the meeting, other than the report that [[Thales]] recommended that Pythagoras travel to [[Egypt]] in order to further his philosophical and mathematical training. Evidence certainly suggests that the Egyptians had advanced further than the Greeks of their time in [[mathematics]] and [[astronomy]], and many scholars now believe that the [[Egyptians]] used the [[Pythagorean theorem]] in some of their architectural projects before the [[6th century B.C.E.]]. [[India]]n mathematicians were aware of special cases (at least) of the theorem as early as the [[8th century B.C.E.]] (see: [[Baudhayana]]). | Some consider Pythagoras the pupil of [[Anaximander]] and some ancient sources tell of his visiting, in his twenties, the philosopher [[Thales]], just before the death of the latter. No account exists of the specifics of the meeting, other than the report that [[Thales]] recommended that Pythagoras travel to [[Egypt]] in order to further his philosophical and mathematical training. Evidence certainly suggests that the Egyptians had advanced further than the Greeks of their time in [[mathematics]] and [[astronomy]], and many scholars now believe that the [[Egyptians]] used the [[Pythagorean theorem]] in some of their architectural projects before the [[6th century B.C.E.]]. [[India]]n mathematicians were aware of special cases (at least) of the theorem as early as the [[8th century B.C.E.]] (see: [[Baudhayana]]). | ||

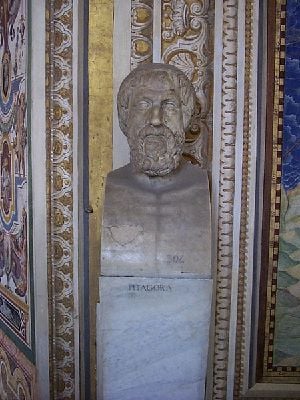

| − | [[Image: | + | [[Image:450px-Pythagoras Bust Vatican Museum.jpg|thumb|Bust of Pythagoras, Vatican Museum, Rome]] |

In [[astronomy]], the Pythagoreans were well aware of the periodic numerical relations of the [[planet]]s, [[moon]], and [[sun]]. The celestial spheres of the planets were thought to produce a harmony called the [[music of the spheres]]. These ideas, as well as the ideas of the [[perfect solid]]s, would later be used by [[Johannes Kepler]] in his attempt to formulate a model of the [[solar system]] in his work ''[[Harmonice Mundi|The Harmony of the Worlds]]''. Pythagoreans also believed that the earth itself was in motion and that the laws of nature could be derived from pure mathematics. It is believed by modern astronomers that Pythagoras coined the term ''[[cosmos]]'', a term implying a universe with orderly movements and events. | In [[astronomy]], the Pythagoreans were well aware of the periodic numerical relations of the [[planet]]s, [[moon]], and [[sun]]. The celestial spheres of the planets were thought to produce a harmony called the [[music of the spheres]]. These ideas, as well as the ideas of the [[perfect solid]]s, would later be used by [[Johannes Kepler]] in his attempt to formulate a model of the [[solar system]] in his work ''[[Harmonice Mundi|The Harmony of the Worlds]]''. Pythagoreans also believed that the earth itself was in motion and that the laws of nature could be derived from pure mathematics. It is believed by modern astronomers that Pythagoras coined the term ''[[cosmos]]'', a term implying a universe with orderly movements and events. | ||

| Line 87: | Line 84: | ||

*[http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/pythagoras/ Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry] | *[http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/pythagoras/ Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry] | ||

| − | + | '''Pythagoreanism''' is a term used for the [[esoteric]] and [[metaphysics|metaphysical]] beliefs held by [[Pythagoras]] and his followers the Pythagoreans, much influenced by [[mathematics]] and probably a main inspiration source to [[Plato]] and [[platonism]]. | |

| + | |||

| + | One main subject that is part of pythagoreanism is [[musica universalis]], the ''music of the spheres''. Some [[Surat Shabd Yoga|Surat Shabda Yoga]], [[Satguru]]s considered the music of the spheres to be a term synonymous with the Shabda or the Audible Life Stream in that tradition, because they considered Pythagoras to be a Satguru as well. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The '''Pythagoreans''' were a [[Hellenic Greece|Hellenic]] [[organization]] of [[astronomer]]s, [[musician]]s, [[mathematician]]s, and [[philosopher]]s who believed that all things are, essentially, [[number|numeric]]. The group strove to keep the discovery of [[irrational number]]s a secret, and legends tell of a member being [[drowning|drowned]] for breaching this secrecy (see [[Hippasus]]). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Later resurgence of the same ideas are collected under the term '''neopythagoreanism'''. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Influence== | ||

| + | |||

| + | The word '[[vegetarian]]' was coined in 1847 when the British Vegetarian Society was formed. Before this, vegetarians were known as Pythagoreans. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The [[pentagram]] (five-pointed star) was an important religious symbol used by the Pythagoreans. It was called "health". | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Pythagorean cosmology== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Pythagorean thought was dominated by mathematics, but it was also profoundly mystical. In the area of cosmology there is less agreement about what [[Pythagoras]] himself actually taught, but most scholars believe that the Pythagorean idea of the [[reincarnation|transmigration of the soul]] is too central to have been added by a later follower of Pythagoras. On the other hand it is impossible to determine the origin of the Pythagorean account of substance. It seems that the Pythagorean account begins with [[Anaximander]]'s account of the ultimate substance of things as "the boundless." Another of Anaximander's pupils, Anaximenes, who was a contemporary of Pythagoras, gave an account of how Anaximander's "boundless" took form, through condensation and refraction. On the other hand, the Pythagorean account says that it is through the notion of the "limit" that the "boundless" takes form. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Diogenes Laërtius|Diogenes Laertius]] (about AD 200) quotes [[Alexander Polyhistor]]'s (about 100 B.C.E.) book ''[[Successions of Philosophers]]'' (and according to Diogenes, Alexander had access to a book called ''The Pythagorean Memoir'') in his account of how the Pythagorean cosmology was constructed (Diogenes Laertius, ''[[Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers|Vitae philosophorum VIII]]'', 24): | ||

| + | |||

| + | :The principle of all things is the [[monad]] or unit; arising from this monad the undefined dyad or two serves as material substratum to the monad, which is cause; from the monad and the undefined dyad spring numbers; from numbers, points; from points, lines; from lines, plane figures; from plane figures, solid figures; from solid figures, sensible bodies, the elements of which are four, fire, water, earth and air; these elements interchange and turn into one another completely, and combine to produce a universe animate, intelligent, spherical, with the earth at its centre, the earth itself too being spherical and inhabited round about. There are also antipodes, and our ‘down' is their ‘up'. | ||

| + | |||

| + | This cosmology also inspired the Arabic [[gnosticism|gnostic]] [[Monoimus]] to combine this system with [[monism]] and other things to form his own cosmology. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Reference== | ||

| + | * '''Pythagoras Revived''', Patrick J. O'Meara, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1989. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==See also== | ||

| + | * [[Pythagoras]] | ||

| + | *[[Neo-Pythagoreanism]] | ||

| + | * [[Pythagorean tuning]] | ||

| + | * [[Esoteric cosmology]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | == External links == | ||

| + | * [http://users.ucom.net/~vegan Pythagoreanism Web Site] | ||

| + | * [http://cyberspacei.com/jesusi/inlight/philosophy/western/Pythagoreanism.htm Pythagoreanism Web Article] | ||

| + | * [http://groups.yahoo.com/group/Pythagorean-L Pythagoreanism Discussion Group] | ||

| + | * [http://www.ivu.org/faq/definitions.html Vegetarianism and Pythagoreanism] | ||

[[Category:582 B.C.E. births]] | [[Category:582 B.C.E. births]] | ||

| Line 100: | Line 134: | ||

{{credit|26327028}} | {{credit|26327028}} | ||

| + | {{credit|31739915}} | ||

Revision as of 03:32, 23 December 2005

Template:Cleanup-priority

Pythagoras (582 B.C.E. – 496 B.C.E., Greek: Πυθαγόρας) was an Ionian mathematician and philosopher, known best for formulating the Pythagorean theorem.

Known as "the father of numbers", he made influential contributions to philosophy and religious teaching in the late 6th century B.C.E. Because legend and obfuscation cloud his work even more than with the other pre-Socratics, one can say little with confidence about his life and teachings. Pythagoras and his students believed that everything was related to mathematics, and felt that everything could be predicted and measured in rhythmic cycles.

Biography

Pythagoras was born on the island of Samos, off the coast of Asia Minor. He was born to Pythais (a native of Samos) and Mnesarchus (a merchant from Tyre). As a young man he left his native city for Crotona in Southern Italy, to escape the tyrannical government of Polycrates. Many writers credit him with visits to the sages of Egypt and Babylon before going west; but such visits feature stereotypically in the biographies of many Greek wise men, and are likely more legend than fact.

Upon his migration from Samos to Crotona, Pythagoras established a secret religious society very similar to, and possibly influenced by, the earlier Orphic cult.

Pythagoras undertook a reform of the cultural life of Croton, urging the citizens to follow virtue and form an elite circle of followers around himself. Very strict rules of conduct governed this cultural center. He opened his school to men and women students alike. They called themselves the Mathematikoi; a secret society of sorts.

According to Iamblichus, the Pythagoreans followed a structured life of religious teaching, common meals, exercise, reading and philosophical study. We may infer from this that participants required some degree of wealth and leisure to join the inner circle. Music featured as an essential organizing factor of this life: the disciples would sing hymns Apollo together regularly; they used the lyre to cure illness of the soul or body; poetry recitations occurred before and after sleep to aid the memory.

The Pythagorean theorem that bears his name was known much earlier in Mesopotamia and Egypt, but no proofs have been discovered before the proofs offered by the Greeks. Whether Pythagoras himself proved this theorem is not known as it was common in the ancient world to credit to a famous teacher the discoveries of his students.

Pythagoreans

Main articles: Pythagoreans, Pythagoreanism

Pythagoras' followers were commonly called "Pythagoreans." They were mostly philosophers, mathematicians and geometricians who had an influence on the beginning of Euclidian geometry.

The Pythagoreans well known for their teachings of the transmigration of souls, and also for their theory that numbers constitute the true nature of things. They had performed purification rites and followed ascetic, dietary and moral rules which they believed would enable their soul to achieve a higher rank among the gods. Consequentially, they expected they would be set free from the wheel of birth.

The Pythagoreans had also believed that sexes as equal; all slaves were treated humanely, and to respect animals as creatures with souls. The highest purification of the soul was "philosophy," Pythagoras has been credited with the first use of the term.

They had discovered the relationship between musical notes could be expressed in numerical ratios. The Pythagoreans elaborated on a theory of numbers. Ironically, the exact meaning is still disputed by scholars. For a short while, they taught that all things were numbers. Essence of everything is a number. All relationships, even the abstract concepts, could be expressed numerically.

Literary works

No texts by Pythagoras survive, although forgeries under his name — a few of which remain extant — did circulate in antiquity. Critical ancient sources like Aristotle and Aristoxenus cast doubt on these writings. And ancient Pythagoreans usually quoted their master's doctrines with the phrase autos ephe ("he himself said") — emphasizing the essentially oral nature of his teaching. Pythagoras appears as a character in the last book of Ovid's Metamorphoses , where Ovid has him expound upon his philosophical viewpoints.

Scientific contributions

Some consider Pythagoras the pupil of Anaximander and some ancient sources tell of his visiting, in his twenties, the philosopher Thales, just before the death of the latter. No account exists of the specifics of the meeting, other than the report that Thales recommended that Pythagoras travel to Egypt in order to further his philosophical and mathematical training. Evidence certainly suggests that the Egyptians had advanced further than the Greeks of their time in mathematics and astronomy, and many scholars now believe that the Egyptians used the Pythagorean theorem in some of their architectural projects before the 6th century B.C.E. Indian mathematicians were aware of special cases (at least) of the theorem as early as the 8th century B.C.E. (see: Baudhayana).

In astronomy, the Pythagoreans were well aware of the periodic numerical relations of the planets, moon, and sun. The celestial spheres of the planets were thought to produce a harmony called the music of the spheres. These ideas, as well as the ideas of the perfect solids, would later be used by Johannes Kepler in his attempt to formulate a model of the solar system in his work The Harmony of the Worlds. Pythagoreans also believed that the earth itself was in motion and that the laws of nature could be derived from pure mathematics. It is believed by modern astronomers that Pythagoras coined the term cosmos, a term implying a universe with orderly movements and events.

It is sometimes difficult to determine which ideas Pythagoras taught originally, as opposed to the ideas his followers later added. While he clearly attached great importance to geometry, classical Greek writers tended to cite Thales as the great pioneer of this science rather than Pythagoras. The later tradition of Pythagoras as the inventor of mathematics stems largely from the Roman period.

Whether or not we attribute the Pythagorean theorem to Pythagoras, it seems fairly certain that he had the pioneering insight into the numerical ratios which determine the musical scale, since this plays a key role in many other areas of the Pythagorean tradition, and since no evidence remains of earlier Greek or Egyptian musical theories. Another important discovery of this school — which upset Greek mathematics, as well as the Pythagoreans' own belief that whole numbers and their ratios could account for geometrical properties — was the incommensurability of the diagonal of a square with its side. This result showed the existence of irrational numbers.

The influence of Pythagoras has transcended the field of mathematics, and the Hippocratic Oath — with its central commitment to First do no harm — has its roots in the oath of the Pythagorean Brotherhood [1].

See also

- Hippasus

- Pythagoreans

- Pythagoreanism

- Pythagorean comma

- Pythagorean theorem

- Sacred geometry

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

Primary sources:

Only a few relevant source texts deal with Pythagoras and the Pythagoreans, most are available in different translations. Other texts usually build solely on information from these four books.

- Diogenes Laertius, Vitae philosophorum VIII (Lives of Eminent Philosophers, which in turn reference the lost work Successions of Philosophers by Alexander Polyhistor) — Pythagoras, Translation by C.D. Yonge

- Porphyry, Vita Pythagorae (Life of Pythagoras)

- Iamblichus, De Vita Pythagorica (On the Pythagorean Life)

- Apuleius also writes about Pythagoras in Apologia, including a story of him being taught by Babylonian disciples of Zoroaster

Secondary sources:

- Eric Temple Bell, The Magic of Numbers, Dover, New York, 1991 ISBN 0486267881

- Walter Burkert, Lore and Science in Ancient Pythagoreanism, Harvard University Press (June 1, 1972), ISBN 0674539184

- K. L., Guthrie (Ed.), The Pythagorean Sourcebook and Library, Phanes, Grand Rapids, 1987 ISBN 0-933999-51-8

- Dominic J. O'Meara, Pythagoras Revived, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1989, Paperback ISBN 0198239130, Hardcover ISBN 0198244851

External links

- Pythagoreanism Web Site

- Pythagoras, Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Pythagoras of Samos, The MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, School of Mathematics and Statistics, University of St Andrews, Scotland

- Pythagoras and the Pythagoreans, Fragments and Commentary, Arthur Fairbanks Hanover Historical Texts Project, Hanover College Department of History

- The Complete Pythagoras, an on-line book containing all survived biographies and Pythagorean fragments.

- Pythagoras and the Pythagoreans, Department of Mathematics, Texas A&M University

- Pythagoras and Pythagoreanism, The Catholic Encyclopedia

- Pythagoreanism Web Article

- Pythagoreanism Discussion Group

- Occult conception of Pythagoreanism

- Pythagoras of Samos

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry

Pythagoreanism is a term used for the esoteric and metaphysical beliefs held by Pythagoras and his followers the Pythagoreans, much influenced by mathematics and probably a main inspiration source to Plato and platonism.

One main subject that is part of pythagoreanism is musica universalis, the music of the spheres. Some Surat Shabda Yoga, Satgurus considered the music of the spheres to be a term synonymous with the Shabda or the Audible Life Stream in that tradition, because they considered Pythagoras to be a Satguru as well.

The Pythagoreans were a Hellenic organization of astronomers, musicians, mathematicians, and philosophers who believed that all things are, essentially, numeric. The group strove to keep the discovery of irrational numbers a secret, and legends tell of a member being drowned for breaching this secrecy (see Hippasus).

Later resurgence of the same ideas are collected under the term neopythagoreanism.

Influence

The word 'vegetarian' was coined in 1847 when the British Vegetarian Society was formed. Before this, vegetarians were known as Pythagoreans.

The pentagram (five-pointed star) was an important religious symbol used by the Pythagoreans. It was called "health".

Pythagorean cosmology

Pythagorean thought was dominated by mathematics, but it was also profoundly mystical. In the area of cosmology there is less agreement about what Pythagoras himself actually taught, but most scholars believe that the Pythagorean idea of the transmigration of the soul is too central to have been added by a later follower of Pythagoras. On the other hand it is impossible to determine the origin of the Pythagorean account of substance. It seems that the Pythagorean account begins with Anaximander's account of the ultimate substance of things as "the boundless." Another of Anaximander's pupils, Anaximenes, who was a contemporary of Pythagoras, gave an account of how Anaximander's "boundless" took form, through condensation and refraction. On the other hand, the Pythagorean account says that it is through the notion of the "limit" that the "boundless" takes form.

Diogenes Laertius (about AD 200) quotes Alexander Polyhistor's (about 100 B.C.E.) book Successions of Philosophers (and according to Diogenes, Alexander had access to a book called The Pythagorean Memoir) in his account of how the Pythagorean cosmology was constructed (Diogenes Laertius, Vitae philosophorum VIII, 24):

- The principle of all things is the monad or unit; arising from this monad the undefined dyad or two serves as material substratum to the monad, which is cause; from the monad and the undefined dyad spring numbers; from numbers, points; from points, lines; from lines, plane figures; from plane figures, solid figures; from solid figures, sensible bodies, the elements of which are four, fire, water, earth and air; these elements interchange and turn into one another completely, and combine to produce a universe animate, intelligent, spherical, with the earth at its centre, the earth itself too being spherical and inhabited round about. There are also antipodes, and our ‘down' is their ‘up'.

This cosmology also inspired the Arabic gnostic Monoimus to combine this system with monism and other things to form his own cosmology.

Reference

- Pythagoras Revived, Patrick J. O'Meara, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1989.

See also

- Pythagoras

- Neo-Pythagoreanism

- Pythagorean tuning

- Esoteric cosmology

External links

- Pythagoreanism Web Site

- Pythagoreanism Web Article

- Pythagoreanism Discussion Group

- Vegetarianism and Pythagoreanism

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.