Difference between revisions of "Pine" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 44: | Line 44: | ||

[[Image:StonePine.jpg|thumb|left|Stone Pine cone and seeds]] | [[Image:StonePine.jpg|thumb|left|Stone Pine cone and seeds]] | ||

| − | The '''Stone Pine''' (''Pinus pinea'') was named by [[Linnaeus]] as the "pine of pines" (Peterson 1980). It is probably native to the [[Iberian Peninsula]] ([[Spain]] | + | The '''Stone Pine''' (''Pinus pinea'') was named by [[Linnaeus]] as the "pine of pines" (Peterson 1980). It is probably native to the [[Iberian Peninsula]] ([[Spain]] and [[Portugal]]) but was spread by man since prehistoric times throughout the Mediterranian region. Its large (about 2 cm, 0.8 inches long) seeds were a valuable food crop. The "Stone" in its name refers to the seeds. Besides being eaten by humans Stone Pine seeds are also eaten by [[birds]] and [[mammals]], especially the Azure-winged Magpie. A [[symbiosis|symbiotic]] relationship exists between the trees and the animals in which both benefit because the animals bury some of the seeds for future use. Many are never dug up and sprout and grow new trees. The animals get a steady food source and the trees have a way to disperse their seeds far more widely than they otherwise would. These same type of relationships exist between many species of pine and animals around the world; [[Squirrel]]s and their relatives and members of the [[crow]] family such as jays and magpies being the most common animal partners (Pielou 1988 pp 137-141). |

Stone Pines are still valued by humans for their seeds but now more are grown as ornamentals. They are often grown in containers as bonsai trees and living [[Christmas tree]]s. | Stone Pines are still valued by humans for their seeds but now more are grown as ornamentals. They are often grown in containers as bonsai trees and living [[Christmas tree]]s. | ||

| Line 58: | Line 58: | ||

===''Pinus lambertiana'' - Sugar Pine=== | ===''Pinus lambertiana'' - Sugar Pine=== | ||

| − | The '''Sugar Pine''' (''Pinus lambertiana'') is the largest pine commonly growing 40-60 meters (130-200 feet) tall and sometimes as tall as 80 meters (260 feet) or even more. It also has the largest cones of any conifer, up to 66 cm (26 inches) long. It grows in western United States and Mexico mainly in higher elevations. | + | The '''Sugar Pine''' (''Pinus lambertiana'') is the largest pine, commonly growing 40-60 meters (130-200 feet) tall and sometimes as tall as 80 meters (260 feet) or even more. It also has the largest cones of any conifer, up to 66 cm (26 inches) long. It grows in western United States and Mexico mainly in higher elevations. |

The Sugar Pine has been severely affected by the White Pine Blister Rust (''Cronartium ribicola''), a fungus that was accidentally introduced from Europe in 1909. A high proportion of the Sugar Pine has been killed by the blister rust, particularly in the northern part of the species' range (further south in central and southern [[California]], the summers are too dry for the disease to spread easily). The rust has also destroyed much of the Western White Pine and Whitebark Pine outside of California. The US Forest Service has a program for developing rust-resistant Sugar Pine and Western White Pine. Seedlings of these trees have been introduced into the wild. | The Sugar Pine has been severely affected by the White Pine Blister Rust (''Cronartium ribicola''), a fungus that was accidentally introduced from Europe in 1909. A high proportion of the Sugar Pine has been killed by the blister rust, particularly in the northern part of the species' range (further south in central and southern [[California]], the summers are too dry for the disease to spread easily). The rust has also destroyed much of the Western White Pine and Whitebark Pine outside of California. The US Forest Service has a program for developing rust-resistant Sugar Pine and Western White Pine. Seedlings of these trees have been introduced into the wild. | ||

Revision as of 02:56, 11 September 2006

| Pines | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Sugar Pine (Pinus lambertiana) | ||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

| Species | ||||||||||||

|

About 115. |

Pines are coniferous trees of the genus Pinus, in the family Pinaceae. There are about 115 species of pine. They are found naturally only in the Northern Hemisphere (with one very minor exception) where their forests dominate vast areas of land. They have been and continue to be very important to humans, mainly for their wood and also for other products. Besides that their beauty, hardiness, and beneficence have been a source of inspiration to those living in the sometimes difficult northern environments.

There are some conifers growing in the Southern Hemisphere which, although not true pines, resemble them and are sometimes called pines; for instance the Norfolk Island Pine, Araucaria heterophylla, of the South Pacific.

Morphology

Pines are evergreen and resinous. Young trees are almost always conical in shape with many small branches radiating out from a central trunk. In a forest the lower branches may drop off because of lack of sunlight and older trees may develop a flattened crown. In some species and in some environments mature trees can have a branching, twisted form (Dallimore 1966 p 385). The bark of most pines is thick and scaly, but some species have thin, flaking bark.

Foliage

Pines have four types of leaves. Seedlings begin with a whorl of 4-20 seed leaves (cotyledons), followed immediately by juvenile leaves on young plants, 2-6 cm (1 -2 inches) long, single, green or often blue-green, and arranged spirally on the shoot. These are replaced after six months to five years by scale leaves, similar to bud scales, small, brown and non-photosynthetic, and arranged like the juvenile leaves; and the adult leaves or needles, green, bundled in clusters (fascicles) of (1-6) needles together, each fascicle produced from a small bud on a dwarf shoot in the axil of a scale leaf. These bud scales often remain on the fascicle as a basal sheath. The needles persist for 1 to 40 years, depending on species. If a shoot is damaged (e.g. eaten by an animal), the needle fascicles just below the damage will generate a bud which can then replace the lost growth.

Cones

Pines are mostly monoecious, having the male and female cones on the same tree. The male cones are small, typically 1-5 cm (0.4-2 inches) long, and only present for a short period (usually in spring, though autumn in a few pines), falling as soon as they have shed their pollen. The female cones take 1.5-3 years (depending on species) to mature after pollination, with actual fertilization delayed one year. At maturity the cones are 3-60 cm (1-24 inches) long. Each cone has numerous spirally arranged scales, with two seeds on each fertile scale; the scales at the base and tip of the cone are small and sterile, without seeds. The seeds are mostly small and winged, and are anemophilous (wind-dispersed), but some are larger and have only a vestigial wing, and are dispersed by birds or mammals. In others, the fire climax pines, the seeds are stored in closed ("serotinous") cones for many years until a forest fire kills the parent tree; the cones are also opened by the heat and the stored seeds are then released in huge numbers to re-populate the burnt ground.

Classification of Pines

Pines are divided into three subgenera, based on cone, seed and leaf characters:

- Subgenus Strobus (white or soft pines). Cone scale without a sealing band. Umbo terminal. Seedwings adnate. One fibrovascular bundle per leaf.

- Subgenus Ducampopinus (pinyon, lacebark and bristlecone pines). Cone scale without a sealing band. Umbo dorsal. Seedwings articulate. One fibrovascular bundle per leaf.

- Subgenus Pinus (yellow or hard pines). Cone scale with a sealing band. Umbo dorsal. Seedwings articulate. Two fibrovascular bundles per leaf.

Some important pine species

Pinus pinea - Stone Pine

The Stone Pine (Pinus pinea) was named by Linnaeus as the "pine of pines" (Peterson 1980). It is probably native to the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal) but was spread by man since prehistoric times throughout the Mediterranian region. Its large (about 2 cm, 0.8 inches long) seeds were a valuable food crop. The "Stone" in its name refers to the seeds. Besides being eaten by humans Stone Pine seeds are also eaten by birds and mammals, especially the Azure-winged Magpie. A symbiotic relationship exists between the trees and the animals in which both benefit because the animals bury some of the seeds for future use. Many are never dug up and sprout and grow new trees. The animals get a steady food source and the trees have a way to disperse their seeds far more widely than they otherwise would. These same type of relationships exist between many species of pine and animals around the world; Squirrels and their relatives and members of the crow family such as jays and magpies being the most common animal partners (Pielou 1988 pp 137-141).

Stone Pines are still valued by humans for their seeds but now more are grown as ornamentals. They are often grown in containers as bonsai trees and living Christmas trees.

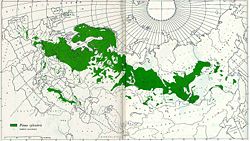

Pinus sylvestris - Scots Pine

The Scots Pine (Pinus sylvestris) has the widest distribution of any pine, growing wild across northern Europe and Asia from the Atlantic to the Pacific. It grows well in a wide range of soils and conditions and is reclaiming (or being replanted in) areas where its forests had been cut down in the past. It is the most important tree for timber in Europe, producing very good quality wood for many construction purposes (Dallimore 1966 p 493)

Scots Pine has also been widely planted in New Zealand and much of the colder regions of North America; it is listed as an invasive species in some areas there, including Ontario and Wisconsin. In the United States many are grown on Christmas tree farms.

Pinus densiflora - Japanese Red Pine

The Japanese Red Pine (Pinus densiflora) has a home range that includes Japan, Korea, northeastern China and the extreme southeast of Russia. It is closely related to the Scots Pine and like it is of medium height (mostly under 35 meters - 115 feet). It is the most common tree in Japan and is the most important source of timber there. It is also admired for its beauty in traditional Japanese gardens and as a bonzai tree (Dallimore 1966 p 423-425).

Pinus lambertiana - Sugar Pine

The Sugar Pine (Pinus lambertiana) is the largest pine, commonly growing 40-60 meters (130-200 feet) tall and sometimes as tall as 80 meters (260 feet) or even more. It also has the largest cones of any conifer, up to 66 cm (26 inches) long. It grows in western United States and Mexico mainly in higher elevations.

The Sugar Pine has been severely affected by the White Pine Blister Rust (Cronartium ribicola), a fungus that was accidentally introduced from Europe in 1909. A high proportion of the Sugar Pine has been killed by the blister rust, particularly in the northern part of the species' range (further south in central and southern California, the summers are too dry for the disease to spread easily). The rust has also destroyed much of the Western White Pine and Whitebark Pine outside of California. The US Forest Service has a program for developing rust-resistant Sugar Pine and Western White Pine. Seedlings of these trees have been introduced into the wild.

Pinus longaeva - Great Basin Bristlecone Pine

The Great Basin Bristlecone Pine (Pinus longaeva) is the longest lived of all living things of earth today. The oldest living today grows in the White-Inyo mountain range of California and has been given the name "Methuselah"; in 2006 it was 4767 years old, over a thousand years older than any other tree (Miller, 2006). The Great Basin Bristlecone Pine grows only in a few mountain ranges in eastern California, Utah, and Nevada and only at high elevations of 2,600-3,550 meters (8,500-11,650 feet) (Lanner 1999 p47). Besides the tree itself, its leaves show the longest persistence of any plant, with some remaining green for 45 years (Ewers & Schmid 1981).

The growth rings of Great Basin Bristlecone Pines have been studied as a way of dating objects from the past and to study past climate changes. By studying both living and dead trees a continuous record has been established going back 10,000 years, which is the end of the last ice age. In 1964 a tree in Nevada 4,862 years old (older than "Methuselah") was cut down in the process of growth ring study (dendrochronology) due to a misunderstanding. The protests that followed led to a greater concern for the trees' protection which contributed to the establishment of Great Basin National Park in 1986. The tree that was cut down had been named "Prometheus" (Miller 2006).

Pinus radiata - Monterey Pine or Radiata Pine

Pinus radiata is known in English as Monterey Pine in some parts of the world (mainly in the USA, Canada and the British Isles), and Radiata Pine in others (primarily Australia, New Zealand and Chile). It is native to coastal California in three very limited areas and also on two islands off the coast of Mexico. In its native range it is threatened by disease and on one island by feral goats. However it has been transplanted to other areas of the world which have similar climates to coastal California, especially in the Southern Hemisphere where pines are not native. There is grown for timber and pulpwood on plantations which in 1999 totaled over 10,000,000 acres, about 1,000 times the area of its natural range (Lanner 1999).

Uses

Pines are commercially among the most important of species used for timber in temperate regions of the world. Many are grown as a source of wood pulp for paper manufacture. Some factors are that they are fast-growing softwoods that can be planted in relatively dense stands and because their acidic decaying needles may inhibit the growth of other competing plants in the cropping areas. The fact that in most species used for timber most of the wood is concentrated in the trunk rather than the branches also makes them easier to harvest and process (Dallimore 1966 p 385).

The resin of some species is important as the source of turpentine. Some pines are used for Christmas trees, and pine cones are also widely used for Christmas decorations. Many pines are also very attractive ornamental trees planted in parks and large gardens. A large number of dwarf cultivars have been selected, suitable for planting in smaller gardens.

Nutritional use

The seeds of some pines are a good food source and have been important especially in the Mediterranean region and southwestern North America. The inner bark of the tree can also be eaten and is a good source of food in times of famine or emergency. Tea can be brewed from the needles.

Inspiration

Robert Lovett, the founder of the Lovett Pinetum in Missouri, USA writes:

- However, there are special physical qualities of this genus. It has more species, geographic distribution and morphologic diversity than any of the other gymnosperms, with more tendency for uniquely picturesque individuals than, say, spruces and firs. The pines have oils that transpirate through their needle stomata and evaporate from sap resin in wounds and growing cones which provides a pleasant fragrance unmatched by other genera. Many of them have edible seeds that provide an essential link in the ecology of their habitats. A special sound when the wind blows through their needles, a special sun and shadow pattern on the ground under a pine tree ------that sort of stuff which sounds pretty corny but which has long been a source of inspiration for poets, painters, and musicians. Some of this veneration really does relate to their unique physical beauty and longevity. They are a symbol of long life and beauty in much of the Far East, sacred to Zeus and the people of ancient Corinth, worshiped in Mexico and Central America and an object of affection for early American colonists. Longfellow wrote "we are all poets when we are in the pine woods." (Lovett 2006 p 13).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Dallimore, W. & Jackson, A.B. revised by Harrison, S.G., 1967, A Handbook of Coniferae and Ginkgoaceae, New York : St. Martin's Press

- Ewers, F. W. & Schmid, R., 1981, Longevity of needle fascicles of Pinus longaeva (Bristlecone Pine) and other North American pines. Oecologia 51: 107-115.

- Farjon, A. 1984, 2nd edition 2005. Pines. Leiden, UK : E. J. Brill, ISBN 90-04-13916-8

- Lanner, R.M., 1999, Conifers of California, Los Alivos, California : Cachuma Press ISBN 0962850535

- Little, E. L., Jr., and Critchfield, W. B. 1969. Subdivisions of the Genus Pinus (Pines). US Department of Agriculture Misc. Publ. 1144 (Superintendent of Documents Number: A 1.38:1144).

- Lovett, R., The Lovett Pinetum Charitable Foundation, 2006, Website [1]

- Miller, L., 2006, The Ancient Bristlecone Pine, Website [2]

- Mirov, N. T. 1967. The Genus Pinus, New York : Ronald Press (out of print).

- Peterson, R., 1980, The Pine Tree Book, New York : The Brandywine Press ISBN 0896160068

- Pielou, E.C., 1988, The World of Northern Evergreens, Ithica, New York : Cornell University ISBN 0801421160

- Richardson, D. M. (ed.). 1998. Ecology and Biogeography of Pinus, Cambridge, UK : Cambridge University Press, . 530 p. ISBN 0-521-55176-5

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.