Difference between revisions of "Monothelitism" - New World Encyclopedia

m (→Details) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (54 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Images OK}}{{submitted}}{{approved}}{{copyedited}} |

| − | '''Monothelitism''' ( | + | [[Image:Christ in Gethsemane.jpg|thumb|250px|Christ in [[Gethsemane]]: Was [[Jesus]]' human will distinct from the will of [[God]]?]] |

| + | '''Monothelitism''' (from the [[Greek]], referring to "one will") was a theological doctrine and movement influential in the seventh century C.E. Its teaching was that [[Christ]]'s human will was at all times completely one with the will of [[God]]. | ||

| − | + | An outgrowth of the [[Monophysitism|Monophysite controversy]] from the previous two centuries, Monothelitism held that while Christ had two natures (both human and divine), he had only one will (divine/human), which is not distinguishable from the will of God. Simultaneously the orthodox view holds that [[Jesus]] had both a [[human being|human]] will and a [[divine]] will. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Evidence indicates that resulting from the suggestion of Emperor [[Heraclius]] (610–641), the Monothelite position was promulgated by [[Patriarch Sergius I of Constantinople]]. This succeeded for a time in reconciling the Monophysite churches of the East and Africa with the [[Council of Chalcedon]]. In its early stages, the idea was either endorsed or tolerated by [[Pope Honorius I]] (625–638). After Honorius' death, however, Monothelitism was strongly opposed by succeeding [[popes]]. In the East, it was supported by several emperors and leading Christian patriarchs, resulting in a bitterly contested [[schism]], giving rise to the [[martyr]]dom of the orthodox figures [[Pope Martin I]] and Saint [[Maximus the Confessor]], among others. | |

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | Monothelitism was finally condemned at the [[Third Council of Constantinople]] (the Sixth [[Ecumenical Council]] (680–681), which also declared Honorius I to be a heretic. It came to an end only after the last Monothelite Emperor, [[Philippicus Bardanes]], was removed from power in the early eighth century C.E. | ||

| − | + | ==Background== | |

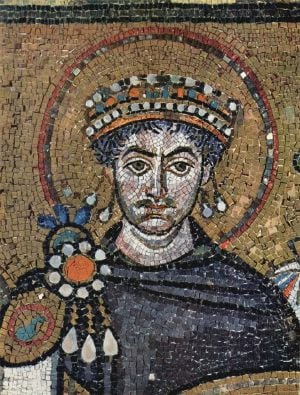

| + | [[Image:Meister von San Vitale in Ravenna 004.jpg|thumb|[[Justinian I]] was one of several emperors who had tried unsuccessfully to reconcile the [[Monophysite]]s and "orthodox" Christians.]] | ||

| + | Monothelitism grew out of the [[Christology|christological]] controversies dealing with the question of whether Christ had one nature (divine/human) or two (divine and human). In these bitter and contentious debates, which often divided the eastern and western Christian churches, the [[nestorianism|Nestorians]] had emphasized two distinct natures in Christ, the [[Monophysite]]s had insisted on one nature in which Christ's divinity and humanity were fully harmonized, and the "Orthodox" ultimately prevailed with a formula which upheld the idea of "two natures" but rejected the notion that these natures were in any way distinct from one another. The definition of the [[Council of Chalcedon]] thus states that Jesus was one person with two natures and that these two natures are "without distinction or confusion." | ||

| − | + | In the short run, however, this formula proved inadequate to solve the problem, being considered far too "Nestorian" for Monophysite churchmen. Many churches, especially in the East and Africa, remained Monophysite, and various formulas were attempted by the eastern Emperors to reconcile the opposing factions, resulting more often than not in even more division and bitter feuds between [[Constantinople]] and the Roman [[papacy]]. | |

| − | Monothelitism | + | Monothelitism emerged as another compromise position, in which the former Monophysites might agree that [[Jesus]] had two natures if it were also affirmed that his will was completely united with that of God. It was also hoped that [[Council of Chalcedon|Chalcedonian]] Christians might agree that Jesus' will was always united with the will of God, as long as it was also affirmed that Christ also had two natures. |

| + | |||

| + | The terminology of the Monothelite controversy is highly technical, causing even one pope, Honorius, to stumble into this "[[heresy]]." At stake was the question as to whether Jesus was truly "human," for if his will was always that of God, how could he share in people's humanity or be truly tempted by [[Satan]], as the Bible reports he was? Moreover, if Jesus had only one (completely divine, yet also human) will, how can one explain his agony in the [[Garden of Gethsemane]], when he himself appears to make a distinction between his will and that of God? Monothelytes sometimes dealt with this objection with reference to "one operation" of Christ's will, meaning his will always operated in union with God's will, even though, as a human being he might be tempted to act otherwise. | ||

==Details== | ==Details== | ||

| − | + | [[Image:Sophronius of Jerusalem.jpg|thumb|120px|Saint [[Sophrinius]] of Jerusalem led the early opposition to Monothelitism]] | |

| + | [[Image:Heraclius-coin2.jpg|thumb|300px|left|Coin bearing the image of [[Emperor Heraclius]]]] | ||

| − | + | Though not a trained theologian, Patriarch [[Sergius I of Constantinople]], as the [[bishop]] of the capital city of the [[Byzantine Empire]], held a position of authority among the Christian churches rivaled only by that of the [[bishop of Rome]]. Sergius wrote that [[Emperor Heraclius]] came to Armenia about 622 during a military campaign, where he disputed with a Monophysite leader named Paul, refuting his claims by arguing for two "natures" in Christ but admitting "one operation" in terms of Christ's will. Later on, the emperor inquired of Bishop [[Cyrus of Alexandria|Cyrus of Phasis]] whether his words were correct. Cyrus was uncertain, and at the emperor's order, he wrote to Sergius in Constantinople, whom Heraclius greatly trusted, for advice. Sergius in reply sent him a letter citing several authorities, including the late [[Pope Vigilius]], in support of "one operation" and "one will." In June, 631, Cyrus was promoted by the emperor to the important position of patriarch of [[Alexandria]]. | |

| − | In | + | Practically the whole of Egypt was at this time still [[Monophysite]]. Former emperors had made efforts toward reunion, to little success. In the late fifth century, the compromise document known as the [[Henotikon]] of Emperor [[Zeno]] had resulted in the so-called [[Acacian schism]] between [[Rome]] and [[Constantinople]] and yet was rejected by many Monophysites, as well as the [[pope]]s. In the sixth century, [[Justinian I]]'s condemnation of the allegedly Nestorian [[Three Chapters]] had nearly caused a another schism between East and West without in the least placating the Monophysites. |

| − | + | In Alexandria, Cyrus was for the moment more successful. He obtained the acceptance by the Monophysites of a series of nine theological points, in which Christ's "one operation" of divine/human will was asserted along with the Chalcedonian "two natures" and "one composite (divine/human) [[hypostasis]] (person)." Through this formula, Cyrus effected the reunion of the Alexandrian church and nearly all of the Egyptian and northern African churches as well. | |

| − | + | However, the future Saint [[Sophronius]]—a much venerated [[monk]] of [[Palestine]], soon to become patriarch of Jerusalem, who was in Alexandria at this time—strongly objected to the expression "one operation." He thus went to [[Constantinople]] and urged Patriarch Sergius that the seventh of the nine "chapters" promoted by Cyrus, affirming "one operation," must be withdrawn. Sergius was not willing to risk losing the African churches again by ordering this, but he did write to Cyrus that it would be well in the future to drop both the expressions "one operation" and "two operations." He also advised referring the question to the [[pope]]. Cyrus, who had much to lose by dropping the idea of "one operation," politely responded that Sergius was, in effect, declaring the emperor to be wrong. | |

| − | He | + | ===Honorius endorses 'one Will'=== |

| + | [[Image:Onorio I - mosaico Santa Agnese fuori le mura.jpg|thumb|[[Pope Honorius I]], whose seeming endorsement of Monothelitism was later condemned as [[heresy]]]] | ||

| + | In his letter to [[Pope Honorius I]], Sergius went so far as to admit that "one operation," though used by several [[Church Fathers]], is a strange expression that might suggest a denial of the "unconfused union of the two natures" (of Christ). However, he also argued that the idea of "two operations" is equally if not more dangerous, suggesting "two contrary wills" at war within Jesus. He concluded that it is best to confess that "from one and the same incarnate Word of God (Jesus) proceed indivisibly and inseparably both the divine and the human operations." | ||

| − | Honorius replied by praising Sergius for rejecting | + | Honorius replied by praising Sergius for rejecting "two operations," approving his recommendations, and refraining from criticizing any of the propositions of Cyrus. In a crucial sentence, he also stated that "We acknowledge one Will of our Lord Jesus Christ." |

| − | Late in 638 the ''Ecthesis of Heraclius'' was issued, composed by Sergius and authorized by the emperor. | + | ===The ''Ecthesis'' of Heraclius=== |

| + | Late in 638, the ''Ecthesis of Heraclius'' was issued, composed by Sergius and authorized by the emperor. Sergius himself died on December 9 of that year, a few days after having celebrated a church council in which the ''Ecthesis'' was acclaimed as "truly agreeing with the Apostolic teaching" of popes Honorius and Vigilius. Cyrus of Alexandria received the news of this council with great joy. | ||

| − | + | The ''Ecthesis'' reaffirmed the doctrines of five [[Ecumenical Council]]s, including Chalcedon, but added a prohibition against speaking of either "one operation" or "two operations," at the same time affirming the "one will in Christ lest contrary wills should be held." Honorius, meanwhile, had died on October 12 and was not in a position to confirm whether this statement conformed with his view. | |

| − | When Heraclius died in February 641, the pope wrote to | + | Papal envoys promised to submit the ''Ecthesis'' to [[Pope Severinus]], but the new pope was not consecrated until May, 640 and died just two months later without having offered his opinion on the ''Ecthesis''. Pope [[John IV]], who succeeded him in December, quickly convened a [[synod]] which, to the emperor's surprise, formally condemned it. Emperor Heraclius, thinking the ''Echthesis'' had only promulgated the view of Pope Honorius, now disowned the ''Echthesis'' in a letter to John IV and laid the blame on Sergius. When Heraclius died in February 641, the pope wrote to his successor, [[Constantine III (Byzantine emperor)|Constantine III]], expecting that the ''Ecthesis'' would now be withdrawn and also apologizing for Pope Honorius, who, he said, had not meant to teach "one will" in Christ. |

| − | However, the new patriarch | + | However, the new patriarch, Pyrrhus, was a supporter of the ''Ecthesis'' and the document was soon confirmed in a major church council at [[Constantinople]]. In [[Jerusalem]], the orthodox champion [[Sophronius]] was succeeded by a supporter of the ''Ecthesis'', and another Monothelite bishop now sat in the see of [[Antioch]]. In [[Alexandria]], the city fell into the hands of the [[Muslim]]s in 640. Among the great cities of the empire, only [[Rome]] thus remained "orthodox," while Constantinople, Antioch, Jerusalem, and Alexandria were Monothelite, the latter soon to become Muslim. |

| − | + | ===Constans II and his ''Type''=== | |

| + | [[Image:Theodorus I.jpg|thumb|Pope Theodore I]] | ||

| + | [[Constans II]] became the new emperor in 641, and like others before him he attempted a reconciliation between the factions based on a policy of banning either extreme, a policy doomed to failure. In May 643, the bishops of Cyprus, independent of any patriarch, held a synod against the ''Ecthesis'', entreating [[Pope Theodore I]], who had ascended to the throne of [[Saint Peter]] the previous year, for support, declaring themselves ready to be martyred rather than forsake the "orthodox" doctrine of "two wills." In 646 certain bishops of Africa and the adjoining islands also held councils and likewise wrote afterward to Theodore in solidarity. | ||

| − | + | The situation now deteriorated into violence. Although Emperor Constans had exiled Patriarch Pyrrhus to Africa, his successor, Paul, continued to support the ''Ecthesis''. Pope Theodore, from Rome, pronounced a sentence of deposition against Paul, and the patriarch retaliated by destroying the Latin altar which belonged to the Roman see at Constantinople. He also punished the papal representatives in Constantinople, as well as certain laymen and priests who supported the Roman position, by imprisonment, exile, or whipping. | |

| − | + | Paul clearly believed himself to be in accord with two previous popes, Honorius and Vigilis; but he was not unwilling to compromise in the name of unity. He therefore persuaded the emperor to withdraw the ''Ecthesis'' and to substitute an orthodox confession of faith together with a disciplinary measure forbidding controversial expressions regarding Christ's will. No blame was to attach to any who had used such expressions in the past, but transgression of the new law would involve deposition for [[bishop]]s and clerics, [[excommunication]] and expulsion for [[monk]]s, loss of office and dignity for officials, fines for richer laymen, and corporal punishment and permanent exile for the poor. Known as the ''Type of Constans'' it was enacted sometime between September 648 and September 649, and it proved to be even less successful than the ''Ecthesis'' had been. | |

| − | + | Pope Theodore died May 5, 649, and was succeeded in July by Pope [[Martin I]]. In October, Martin held a great council at the [[Lateran]], at which 105 bishops were present. The council admitted the good intention of the ''Type'' (apparently so as to spare the emperor while condemning Patriarch Paul), but declared the document heretical for forbidding the teaching of "two operations" and "two wills." It passed 20 [[canons]], the eighteenth of which [[anathema]]tized Cyrus, Sergius, Pyrrhus, Paul, the ''Ecthesis'', and the ''Type''. (Pope Honorius, who had caused so much trouble by seeming to endorse the "one will," however, escaped criticism.) An encyclical letter summarizing the proceedings was sent to churches and monasteries throughout the empire in the name of Pope Martin I and the council. | |

| − | + | ===Martyrdoms=== | |

| + | [[Image:Pope Martin I.jpg|thumb|left|150px|Pope [[Martin I]] became a martyr rather than submit to the ''Type of Constans'']] | ||

| − | + | The pope now moved forcefully against pro-Monothelite churchmen under his jurisdiction. He commissioned Bishop John of Philadelphia to appoint orthodox [[bishop]]s, [[priest]]s, and [[deacon]]s in the patriarchates of [[Antioch]] and [[Jerusalem]]. Martin also deposed Archbishop John of Thessalonika and declared the appointments of [[Macarius of Antioch]] and [[Peter of Alexandria]] to be null and void. | |

| − | + | Emperor Constans retaliated by having Martin kidnapped from [[Rome]] and taken as a prisoner to [[Constantinople]]. The pope still refused to accept either the ''Ecthesis'' or the ''Type,'' and he died a [[martyr]] in the Crimea in March 655. Other famous martyrs in the controversy include [[Maximus the Confessor]] (662), his disciple and fellow monk, [[Anastasius]] (662), and another Anastasius who was a papal envoy (666). | |

| + | |||

| + | Patriarch Paul of Constantinople, meanwhile, died of natural causes. His successor, Peter, sent an ambiguous letter to [[Pope Eugenius]], which made no mention of either one or two "operations," thus observing the prescription of the ''Type''. In 663, Constans came to Rome, intending to make it his residence. The new pope, [[Pope Vitalian|Vitalian]], received him with all due honor, and Constans—who had refused to confirm the elections of Martin and Eugenius—ordered the name of Vitalian to be inscribed on the diptychs of Constantinople. No mention seems to have been made of the ''Type,'' and Constans soon retired to [[Sicily]], where he was murdered in his bath in 668. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===The Sixth Ecumenical Council=== | ||

| + | The new emperor, Constantine Pogonatus, does not seem to have enforced the ''Type,'' although it was not abolished. In 678, he summoned a general council to effect unity between the Eastern and Western churches. He wrote in this sense to [[Pope Donus]] (676-78), who had already died; but [[Pope Agatho]] convened a council at Rome toward this end. The emperor, for his part, sent the Monothelite Patriarch Theodore of Constantinople into exile, as he had become an obstacle to reunion. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Agatho.gif|thumb|Pope Agatho]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | The first session of the [[Sixth Ecumenical Council]] took place at Constantinople on November 7, 680, with Emperor Constantine Pogonatus presiding. Patriarch [[Macarius of Antioch]] was outspoken for Monothelitism, but with the emperor now opposed to this cause, Marcarius was condemned as a heretic. George, the new patriarch of Constantinople, generally upheld the Roman view. However, as Macarius had appealed to the late Pope Honorius, this pope was likewise condemned, a serious embarrassment to the [[papacy]]. The final decree of the council condemns the ''Ecthesis'' and the ''Type'' and several heretics, including Honorius, while affirming the letters of [[Pope Agatho]] and his council. As Agatho had died before receiving the results of the council, it fell to Pope [[Leo II]] to confirm it, and thus the churches of the East and West were once again united. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Monothelism still refused to die, however, and in 711, the imperial throne was seized by [[Philippicus Bardanes]], who had been the pupil of the Monothelite monk Abbot Stephen, an associate of Macarius of Antioch. He restored to the [[diptych]]s the "heretics" Patriarch Sergius, Pope Honorius, and the others condemned by the Sixth Ecumenical Council. He also deposed Patriarch Cyrus of Constantinople and exiled a number of persons who refused to subscribe his condemnation of the council. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Then, in late May 713, Opsikian troops rebelled in [[Thrace]]. Several of their officers penetrated the imperial palace and blinded Philippicus on June 3, 713. Orthodoxy was soon restored by [[Anastasius II]] (713-15). This was, in effect, the end of Monothelitism as a major force. | ||

==Notable Figures in the Monothelite Debate== | ==Notable Figures in the Monothelite Debate== | ||

| − | *[[Patriarch Sergius I of Constantinople]] | + | [[Image:Maximus Confessor.jpg|thumb|Saint Maximus the Confessor]] |

| − | *Bishop [[Cyrus of Alexandria]] | + | *[[Emperor Heraclius]]—Suggested "one operation" of Christ's will and promulgated the ''Echthesis'' as a compromise position, in effect banning the "orthodox" view as well as his own |

| − | *[[Pope Honorius I]] | + | *[[Patriarch Sergius I of Constantinople]]—early supporter of the Monothelitism |

| − | *[[Pope]] [[Martin I]]—Martyred by Byzantine authorities for his condemnation of Monothelitism | + | *Bishop [[Cyrus of Alexandria]]—promoter of Monothelitism as a means of unifying the African churches |

| − | *[[Maximus the Confessor]] | + | *Saint [[Sophrinius]] of Jerusalem—early leader of the opposition to Monothelitism |

| − | *[[Pope Agatho]] | + | *[[Pope Honorius I]]—Endorsed "one will" of Christ, for which he was condemned at Constantinople as a heretic |

| + | *[[Emperor Constans II]]—Persecuted those who affirmed "two wills" | ||

| + | *[[Pope]] [[Martin I]]—Martyred by Byzantine authorities for his condemnation of Monothelitism | ||

| + | *[[Maximus the Confessor]]—Also martyred under Constans II for his opposition to Monothelitism | ||

| + | *[[Pope Agatho]]—Opponent of Monothelitsm whose views were endorsed by the [[Sixth Ecumenical Council]] at Constantinople | ||

==See also== | ==See also== | ||

*[[Monophysitism]] | *[[Monophysitism]] | ||

| − | *[[ | + | *[[Council of Chalcedon]] |

| − | *[[ | + | *[[Maximus the Confessor]] |

| − | *[[ | + | *[[Pope Honorius I]] |

| − | + | *[[Pope Martin I]] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| + | * Allen, Pauline, and Bronwen Neil.'' Maximus the Confessor and His Companions: Documents From Exile''. Oxford early Christian texts. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 2002. ISBN 9780198299912. | ||

| + | * Hardy, Edward Rochie, and Cyril Charles Richardson. ''Christology of the Later Fathers''. Library of Christian classics, v. 3. Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1977. ISBN 978-0664241520. | ||

| + | * Hovorun, Cyril. ''Will, Action and Freedom: Christological Controversies in the Seventh Century''. The medieval Mediterranean, v. 77. Leiden: Brill, 2008. ISBN 9789004166660. | ||

| + | * Kaegi, Walter Emil. ''Heraclius, Emperor of Byzantium''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003. ISBN 9780521814591. | ||

| + | * Neil, Bronwen. ''Seventh-Century Popes and Martyrs: The Political Hagiography of Anastasius Bibliothecarius''. Studia antiqua australiensia, v. 2. Turnhout: Brepols, 2006. ISBN 9782503518879. | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | *[http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/10502a.htm | + | All links retrieved November 9, 2022. |

| − | + | *[http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/10502a.htm Monothelitism and Monothelites] ''Catholic Encyclopedia'' | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

[[Category:Religion]] | [[Category:Religion]] | ||

Latest revision as of 21:11, 9 November 2022

Monothelitism (from the Greek, referring to "one will") was a theological doctrine and movement influential in the seventh century C.E. Its teaching was that Christ's human will was at all times completely one with the will of God.

An outgrowth of the Monophysite controversy from the previous two centuries, Monothelitism held that while Christ had two natures (both human and divine), he had only one will (divine/human), which is not distinguishable from the will of God. Simultaneously the orthodox view holds that Jesus had both a human will and a divine will.

Evidence indicates that resulting from the suggestion of Emperor Heraclius (610–641), the Monothelite position was promulgated by Patriarch Sergius I of Constantinople. This succeeded for a time in reconciling the Monophysite churches of the East and Africa with the Council of Chalcedon. In its early stages, the idea was either endorsed or tolerated by Pope Honorius I (625–638). After Honorius' death, however, Monothelitism was strongly opposed by succeeding popes. In the East, it was supported by several emperors and leading Christian patriarchs, resulting in a bitterly contested schism, giving rise to the martyrdom of the orthodox figures Pope Martin I and Saint Maximus the Confessor, among others.

Monothelitism was finally condemned at the Third Council of Constantinople (the Sixth Ecumenical Council (680–681), which also declared Honorius I to be a heretic. It came to an end only after the last Monothelite Emperor, Philippicus Bardanes, was removed from power in the early eighth century C.E.

Background

Monothelitism grew out of the christological controversies dealing with the question of whether Christ had one nature (divine/human) or two (divine and human). In these bitter and contentious debates, which often divided the eastern and western Christian churches, the Nestorians had emphasized two distinct natures in Christ, the Monophysites had insisted on one nature in which Christ's divinity and humanity were fully harmonized, and the "Orthodox" ultimately prevailed with a formula which upheld the idea of "two natures" but rejected the notion that these natures were in any way distinct from one another. The definition of the Council of Chalcedon thus states that Jesus was one person with two natures and that these two natures are "without distinction or confusion."

In the short run, however, this formula proved inadequate to solve the problem, being considered far too "Nestorian" for Monophysite churchmen. Many churches, especially in the East and Africa, remained Monophysite, and various formulas were attempted by the eastern Emperors to reconcile the opposing factions, resulting more often than not in even more division and bitter feuds between Constantinople and the Roman papacy.

Monothelitism emerged as another compromise position, in which the former Monophysites might agree that Jesus had two natures if it were also affirmed that his will was completely united with that of God. It was also hoped that Chalcedonian Christians might agree that Jesus' will was always united with the will of God, as long as it was also affirmed that Christ also had two natures.

The terminology of the Monothelite controversy is highly technical, causing even one pope, Honorius, to stumble into this "heresy." At stake was the question as to whether Jesus was truly "human," for if his will was always that of God, how could he share in people's humanity or be truly tempted by Satan, as the Bible reports he was? Moreover, if Jesus had only one (completely divine, yet also human) will, how can one explain his agony in the Garden of Gethsemane, when he himself appears to make a distinction between his will and that of God? Monothelytes sometimes dealt with this objection with reference to "one operation" of Christ's will, meaning his will always operated in union with God's will, even though, as a human being he might be tempted to act otherwise.

Details

Though not a trained theologian, Patriarch Sergius I of Constantinople, as the bishop of the capital city of the Byzantine Empire, held a position of authority among the Christian churches rivaled only by that of the bishop of Rome. Sergius wrote that Emperor Heraclius came to Armenia about 622 during a military campaign, where he disputed with a Monophysite leader named Paul, refuting his claims by arguing for two "natures" in Christ but admitting "one operation" in terms of Christ's will. Later on, the emperor inquired of Bishop Cyrus of Phasis whether his words were correct. Cyrus was uncertain, and at the emperor's order, he wrote to Sergius in Constantinople, whom Heraclius greatly trusted, for advice. Sergius in reply sent him a letter citing several authorities, including the late Pope Vigilius, in support of "one operation" and "one will." In June, 631, Cyrus was promoted by the emperor to the important position of patriarch of Alexandria.

Practically the whole of Egypt was at this time still Monophysite. Former emperors had made efforts toward reunion, to little success. In the late fifth century, the compromise document known as the Henotikon of Emperor Zeno had resulted in the so-called Acacian schism between Rome and Constantinople and yet was rejected by many Monophysites, as well as the popes. In the sixth century, Justinian I's condemnation of the allegedly Nestorian Three Chapters had nearly caused a another schism between East and West without in the least placating the Monophysites.

In Alexandria, Cyrus was for the moment more successful. He obtained the acceptance by the Monophysites of a series of nine theological points, in which Christ's "one operation" of divine/human will was asserted along with the Chalcedonian "two natures" and "one composite (divine/human) hypostasis (person)." Through this formula, Cyrus effected the reunion of the Alexandrian church and nearly all of the Egyptian and northern African churches as well.

However, the future Saint Sophronius—a much venerated monk of Palestine, soon to become patriarch of Jerusalem, who was in Alexandria at this time—strongly objected to the expression "one operation." He thus went to Constantinople and urged Patriarch Sergius that the seventh of the nine "chapters" promoted by Cyrus, affirming "one operation," must be withdrawn. Sergius was not willing to risk losing the African churches again by ordering this, but he did write to Cyrus that it would be well in the future to drop both the expressions "one operation" and "two operations." He also advised referring the question to the pope. Cyrus, who had much to lose by dropping the idea of "one operation," politely responded that Sergius was, in effect, declaring the emperor to be wrong.

Honorius endorses 'one Will'

In his letter to Pope Honorius I, Sergius went so far as to admit that "one operation," though used by several Church Fathers, is a strange expression that might suggest a denial of the "unconfused union of the two natures" (of Christ). However, he also argued that the idea of "two operations" is equally if not more dangerous, suggesting "two contrary wills" at war within Jesus. He concluded that it is best to confess that "from one and the same incarnate Word of God (Jesus) proceed indivisibly and inseparably both the divine and the human operations."

Honorius replied by praising Sergius for rejecting "two operations," approving his recommendations, and refraining from criticizing any of the propositions of Cyrus. In a crucial sentence, he also stated that "We acknowledge one Will of our Lord Jesus Christ."

The Ecthesis of Heraclius

Late in 638, the Ecthesis of Heraclius was issued, composed by Sergius and authorized by the emperor. Sergius himself died on December 9 of that year, a few days after having celebrated a church council in which the Ecthesis was acclaimed as "truly agreeing with the Apostolic teaching" of popes Honorius and Vigilius. Cyrus of Alexandria received the news of this council with great joy.

The Ecthesis reaffirmed the doctrines of five Ecumenical Councils, including Chalcedon, but added a prohibition against speaking of either "one operation" or "two operations," at the same time affirming the "one will in Christ lest contrary wills should be held." Honorius, meanwhile, had died on October 12 and was not in a position to confirm whether this statement conformed with his view.

Papal envoys promised to submit the Ecthesis to Pope Severinus, but the new pope was not consecrated until May, 640 and died just two months later without having offered his opinion on the Ecthesis. Pope John IV, who succeeded him in December, quickly convened a synod which, to the emperor's surprise, formally condemned it. Emperor Heraclius, thinking the Echthesis had only promulgated the view of Pope Honorius, now disowned the Echthesis in a letter to John IV and laid the blame on Sergius. When Heraclius died in February 641, the pope wrote to his successor, Constantine III, expecting that the Ecthesis would now be withdrawn and also apologizing for Pope Honorius, who, he said, had not meant to teach "one will" in Christ.

However, the new patriarch, Pyrrhus, was a supporter of the Ecthesis and the document was soon confirmed in a major church council at Constantinople. In Jerusalem, the orthodox champion Sophronius was succeeded by a supporter of the Ecthesis, and another Monothelite bishop now sat in the see of Antioch. In Alexandria, the city fell into the hands of the Muslims in 640. Among the great cities of the empire, only Rome thus remained "orthodox," while Constantinople, Antioch, Jerusalem, and Alexandria were Monothelite, the latter soon to become Muslim.

Constans II and his Type

Constans II became the new emperor in 641, and like others before him he attempted a reconciliation between the factions based on a policy of banning either extreme, a policy doomed to failure. In May 643, the bishops of Cyprus, independent of any patriarch, held a synod against the Ecthesis, entreating Pope Theodore I, who had ascended to the throne of Saint Peter the previous year, for support, declaring themselves ready to be martyred rather than forsake the "orthodox" doctrine of "two wills." In 646 certain bishops of Africa and the adjoining islands also held councils and likewise wrote afterward to Theodore in solidarity.

The situation now deteriorated into violence. Although Emperor Constans had exiled Patriarch Pyrrhus to Africa, his successor, Paul, continued to support the Ecthesis. Pope Theodore, from Rome, pronounced a sentence of deposition against Paul, and the patriarch retaliated by destroying the Latin altar which belonged to the Roman see at Constantinople. He also punished the papal representatives in Constantinople, as well as certain laymen and priests who supported the Roman position, by imprisonment, exile, or whipping.

Paul clearly believed himself to be in accord with two previous popes, Honorius and Vigilis; but he was not unwilling to compromise in the name of unity. He therefore persuaded the emperor to withdraw the Ecthesis and to substitute an orthodox confession of faith together with a disciplinary measure forbidding controversial expressions regarding Christ's will. No blame was to attach to any who had used such expressions in the past, but transgression of the new law would involve deposition for bishops and clerics, excommunication and expulsion for monks, loss of office and dignity for officials, fines for richer laymen, and corporal punishment and permanent exile for the poor. Known as the Type of Constans it was enacted sometime between September 648 and September 649, and it proved to be even less successful than the Ecthesis had been.

Pope Theodore died May 5, 649, and was succeeded in July by Pope Martin I. In October, Martin held a great council at the Lateran, at which 105 bishops were present. The council admitted the good intention of the Type (apparently so as to spare the emperor while condemning Patriarch Paul), but declared the document heretical for forbidding the teaching of "two operations" and "two wills." It passed 20 canons, the eighteenth of which anathematized Cyrus, Sergius, Pyrrhus, Paul, the Ecthesis, and the Type. (Pope Honorius, who had caused so much trouble by seeming to endorse the "one will," however, escaped criticism.) An encyclical letter summarizing the proceedings was sent to churches and monasteries throughout the empire in the name of Pope Martin I and the council.

Martyrdoms

The pope now moved forcefully against pro-Monothelite churchmen under his jurisdiction. He commissioned Bishop John of Philadelphia to appoint orthodox bishops, priests, and deacons in the patriarchates of Antioch and Jerusalem. Martin also deposed Archbishop John of Thessalonika and declared the appointments of Macarius of Antioch and Peter of Alexandria to be null and void.

Emperor Constans retaliated by having Martin kidnapped from Rome and taken as a prisoner to Constantinople. The pope still refused to accept either the Ecthesis or the Type, and he died a martyr in the Crimea in March 655. Other famous martyrs in the controversy include Maximus the Confessor (662), his disciple and fellow monk, Anastasius (662), and another Anastasius who was a papal envoy (666).

Patriarch Paul of Constantinople, meanwhile, died of natural causes. His successor, Peter, sent an ambiguous letter to Pope Eugenius, which made no mention of either one or two "operations," thus observing the prescription of the Type. In 663, Constans came to Rome, intending to make it his residence. The new pope, Vitalian, received him with all due honor, and Constans—who had refused to confirm the elections of Martin and Eugenius—ordered the name of Vitalian to be inscribed on the diptychs of Constantinople. No mention seems to have been made of the Type, and Constans soon retired to Sicily, where he was murdered in his bath in 668.

The Sixth Ecumenical Council

The new emperor, Constantine Pogonatus, does not seem to have enforced the Type, although it was not abolished. In 678, he summoned a general council to effect unity between the Eastern and Western churches. He wrote in this sense to Pope Donus (676-78), who had already died; but Pope Agatho convened a council at Rome toward this end. The emperor, for his part, sent the Monothelite Patriarch Theodore of Constantinople into exile, as he had become an obstacle to reunion.

The first session of the Sixth Ecumenical Council took place at Constantinople on November 7, 680, with Emperor Constantine Pogonatus presiding. Patriarch Macarius of Antioch was outspoken for Monothelitism, but with the emperor now opposed to this cause, Marcarius was condemned as a heretic. George, the new patriarch of Constantinople, generally upheld the Roman view. However, as Macarius had appealed to the late Pope Honorius, this pope was likewise condemned, a serious embarrassment to the papacy. The final decree of the council condemns the Ecthesis and the Type and several heretics, including Honorius, while affirming the letters of Pope Agatho and his council. As Agatho had died before receiving the results of the council, it fell to Pope Leo II to confirm it, and thus the churches of the East and West were once again united.

Monothelism still refused to die, however, and in 711, the imperial throne was seized by Philippicus Bardanes, who had been the pupil of the Monothelite monk Abbot Stephen, an associate of Macarius of Antioch. He restored to the diptychs the "heretics" Patriarch Sergius, Pope Honorius, and the others condemned by the Sixth Ecumenical Council. He also deposed Patriarch Cyrus of Constantinople and exiled a number of persons who refused to subscribe his condemnation of the council.

Then, in late May 713, Opsikian troops rebelled in Thrace. Several of their officers penetrated the imperial palace and blinded Philippicus on June 3, 713. Orthodoxy was soon restored by Anastasius II (713-15). This was, in effect, the end of Monothelitism as a major force.

Notable Figures in the Monothelite Debate

- Emperor Heraclius—Suggested "one operation" of Christ's will and promulgated the Echthesis as a compromise position, in effect banning the "orthodox" view as well as his own

- Patriarch Sergius I of Constantinople—early supporter of the Monothelitism

- Bishop Cyrus of Alexandria—promoter of Monothelitism as a means of unifying the African churches

- Saint Sophrinius of Jerusalem—early leader of the opposition to Monothelitism

- Pope Honorius I—Endorsed "one will" of Christ, for which he was condemned at Constantinople as a heretic

- Emperor Constans II—Persecuted those who affirmed "two wills"

- Pope Martin I—Martyred by Byzantine authorities for his condemnation of Monothelitism

- Maximus the Confessor—Also martyred under Constans II for his opposition to Monothelitism

- Pope Agatho—Opponent of Monothelitsm whose views were endorsed by the Sixth Ecumenical Council at Constantinople

See also

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Allen, Pauline, and Bronwen Neil. Maximus the Confessor and His Companions: Documents From Exile. Oxford early Christian texts. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 2002. ISBN 9780198299912.

- Hardy, Edward Rochie, and Cyril Charles Richardson. Christology of the Later Fathers. Library of Christian classics, v. 3. Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1977. ISBN 978-0664241520.

- Hovorun, Cyril. Will, Action and Freedom: Christological Controversies in the Seventh Century. The medieval Mediterranean, v. 77. Leiden: Brill, 2008. ISBN 9789004166660.

- Kaegi, Walter Emil. Heraclius, Emperor of Byzantium. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003. ISBN 9780521814591.

- Neil, Bronwen. Seventh-Century Popes and Martyrs: The Political Hagiography of Anastasius Bibliothecarius. Studia antiqua australiensia, v. 2. Turnhout: Brepols, 2006. ISBN 9782503518879.

External links

All links retrieved November 9, 2022.

- Monothelitism and Monothelites Catholic Encyclopedia

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.