Difference between revisions of "Moloch" - New World Encyclopedia

(refined intro) |

|||

| (35 intermediate revisions by 9 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Paid}}{{Approved}} {{Submitted}}{{Images OK}} {{copyedited}} |

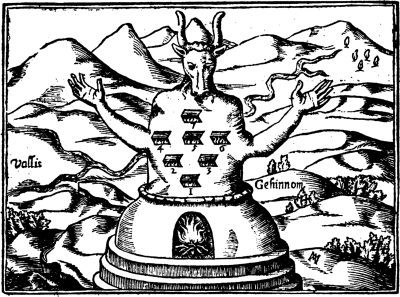

| − | [[Image: | + | [[Image:Molok.jpg|thumb|right|300px|An artist's depiction of Moloch.]] |

| − | |||

| − | + | '''Moloch''' (also rendered as '''Molech''' or '''Molekh,''' from the Hebrew מלך '''mlk''') is a [[Canaanite]] god in the [[Old Testament]] associated with [[human sacrifice]]. Some scholars have suggested that the term refers to a particular kind of sacrifice carried out by the Phoenicians and their neighbors rather than a specific god, though this theory has been widely rejected. Although Moloch is referred to sparingly in the Old Testament, the significance of the god and the sacrificial ritual cannot be underestimated, as the Israelite writers vehemently reject the related practices, regarding them as murderous and idolatrous. | |

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | While no particular form of Moloch is known due to the ambiguity of his origin, he is usually depicted in the form of a calf or an ox, or else as a man with the head of a bull. The figure of Moloch has been an object of fascination over the centuries, and has been used to bolster metaphorical and thematic elements within numerous modern works of art, film, and literature. | ||

| − | + | ==Etymology== | |

| + | The Hebrew letters מלך (''mlk'') usually stand for ''melek'' or “the king,” and were used to refer to the status of the sacrificial god within his [[cult]]. Nineteenth and early twentieth century archaeology has found almost no physical evidence of a god referred to as Moloch or by any similar epithet. Thus, if such a god did exist, ''Moloch'' was not the name he was known by among his worshipers, but rather a Hebrew transliteration. The term usually appears in the Old Testament text as the compound ''lmlk.'' The Hebrew preposition ''l-'' means “to,” but it can often mean “for” or “as a(n).” Accordingly, one can translate ''lmlk'' as "to Moloch," "for Moloch," "as a Moloch," "to the Moloch," "for the Moloch" or "as the Moloch." We also find ''hmlk,'' “the Moloch” standing by itself on one occasion. The written form ''Moloch'' (in the [[Septuagint]] Greek translation of the [[Old Testament]]), or ''Molech'' (Hebrew), is no different than the word ''Melek'' or “king,” which is purposely improperly vocalized by interposing the vowels of the Hebrew term ''bosheth'' or “shameful thing.” This distortion allows the term to express the compunction felt by Israelites who witnessed their brethren worshiping this god of [[human sacrifice]]s, and in doing so prevents them from giving noble status of "king" to what was for all intents and purposes, a false idol. | ||

| − | + | ==Moloch and other gods== | |

| + | A variety of scholars have suggested that Moloch is not an original god himself, but actually an alternative epithet given to another god or gods from cultures who lived in proximity to the Israelites. For instance, some scholars hold that Moloch is actually the Ammonite god Milcom, due to the phonological similarity of the names. While the names are indeed similar, the [[Old Testament]] text clearly differentiates between these deities on several occasions, most notably when referring to the national god of the Ammonites as Milcom and the god of [[human sacrifice]] as Moloch (1 Kings 11.33; Zephaniah 1.5). Further, the Old Testament mostly refers to Molech as Canaanite, rather than Ammonite. The [[Septuagint]] refers to Milcom in 1 Kings 11.7 when referring to [[Solomon]]'s religious failings, instead of Moloch, which may have resulted from a scribal error in the Hebrew. Many English translations accordingly follow the non-Hebrew versions at this point and render Milcom. | ||

| − | + | Other scholars have claimed that Moloch is merely another name for [[Ba'al]], the Sacred Bull who was widely worshiped in the ancient Near East. Ba'al is also frequently mentioned in the Old Testament, sometimes even in proximity to Moloch. Jeremiah 32.35, for instance, refers to rituals dedicated to Ba'al in the Hinnom Valley, with the offering of [[child sacrifice]]s to Moloch. Allusions made to Moloch in the context of the Canaanite fertility cult, which was headed by Ba'al, also suggest a close relationship between the two figures. Further, the [[Bible]] commonly makes reference to burnt offerings being given to Ba’al himself. While these examples could be interpreted to suggest that Moloch and Ba’al are the same god, they more likely refer to the acknowledgement of their close relationship. Again, given the fact that a distinct name is used in the context of sacrifice suggests that Moloch can only be related to Ba'al (perhaps in the faculty of a [[henotheism|henotheistic]] underling) rather than equated with him. | |

| − | The fact that the | + | The fact that the name of Moloch appeared frequently in ancient sources suggests that Moloch was viewed as a distinct [[deity]]. John Day, in his book ''Molech: A God of Human Sacrifice in the Old Testament'' claims that there was indeed a Canaanite god whose name was rendered Melek in the Old Testament. Day cites evidence of this god from the Ugraritic texts, which are serpent charms, where he appears as Malik. Malik, he claims, is equivalent to Nergal, the Mesopotamian god of the underworld who is listed upon god lists from ancient Babylonia. Day concludes that this evidence is consistent with Moloch's malevolent status in the Old Testament, described in Isaiah 57.9 where the prophet parallels sacrifice to Moloch with a journey into the underground world of [[Sheol]]. A god of the underworld is just the kind of god one might worship in the valley of Ben-Hinnom rather than on a hill top. |

| − | == | + | ==Old Testament== |

| − | + | [[File:Foster Bible Pictures 0074-1 Offering to Molech.jpg|thumb|300px|Offering to Molech]] | |

| − | + | Moloch has been most often characterized in the Old Testament by the phrase "to cause to pass through the fire," (h'byrb's in Hebrew) as is used in 2 Kings 23.10. Although this term does not specify on its own whether the ritual related to Moloch involves [[human sacrifice]], the Old Testament clearly interprets it to be so. For example, Isaiah 57.5 states: | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | <blockquote> You who burn with lust among the oaks, under every luxuriant tree; who slay your children in the valleys, under the clefts of rocks. </blockquote> | |

| − | + | Four verses later, Moloch is mentioned specifically: | |

| − | + | <blockquote>You journeyed to Moloch with oil and multiplied your perfumes; you sent your envoys far off, and sent down even to Sheol. (Isaiah 57.9) </blockquote> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | This reference to the underworld suggests that the fate of children is to be sent to death at the hands of Moloch. Thus, although Moloch's role in the Old Testament is small, it is nonetheless important, as his worship most clearly illustrates the more brutal aspects of [[idolatry]] and therefore reinforces the second [[Ten Commandments|commandment]]. [[Leviticus]] 18.21 reads: | |

| − | + | <blockquote>And you shall not let any of your seed pass through Mo'lech, neither shall you profane the name of your God: I am the Lord.</blockquote> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Leviticus 20.2-5 deals with Moloch at length and promises a punishment of death by stoning for perpetration of human sacrifices: | |

| − | + | <blockquote> Whoever he be of the Sons of Israel or of the strangers that sojourn in Israel, that gives any of his seed Mo'lech; he shall surely be put to death: the people of the land shall stone him with stones. And I will set my face against that man and will cut him off from among his people; because he has given of his seed Mo'lech, to defile my sanctuary, and to profane my holy name. And if the people of the land do at all hide their eyes from that man, when he gives of his seed Mo'lech, and do not kill him, then I will set my face against that man, and against his family, and will cut him off, and all that go astray after him, whoring after Mo'lech from among the people. </blockquote> | |

| − | + | Here it becomes evident that it is not only worship of Moloch that is a transgression; failure to identify and punish worshipers of Moloch is also considered to be a grave [[sin]]. Also, the metaphor of prostitution is used in order to convey the sense of spiritual adultery which is being committed against [[God]], or [[Yahweh]], through the worship of Moloch. | |

| − | + | These passages suggest that disdain for Moloch arose due to his worship “alongside” Yahweh, thereby affirming an idolatrous multiplicity of gods. Alternately, Moloch's worship may have been forbidden based on the fact that he was actually “equated” with Yahweh. The prose sections of Jeremiah suggest that there were some worshipers of Moloch who thought Yahweh had commanded the offerings to Moloch based upon the sacrifices of the first born which are mentioned in the [[Pentateuch]] (for instance, Exodus 22.28). [[Book of Jeremiah|Jeremiah]] 32.35 reads: | |

| − | |||

| − | + | <blockquote>And they built the high places of the Ba‘al, which are in the valley of Ben-hinnom, to cause their sons and their daughters to pass through the fire Mo'lech; which I did not command them, nor did it come into my mind that they should do this abomination, to cause Judah to sin.</blockquote> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | <blockquote>And they built the high places of the Ba‘al, which are in the valley of Ben-hinnom, to cause their sons and their daughters to pass through the fire Mo'lech; which I did not command them, nor did it come into my mind that they should do this abomination, to cause Judah to sin.</blockquote> | ||

| − | Moloch | + | This wording suggests that the Israelites may have erroneously developed the idea that Yahweh had decreed such sacrifices to Moloch. This theory is questionable, however, as sacrifices to Moloch were undertaken away from the temple in the valley of Hinnom, in a place commonly referred to as Tophet (as mentioned in 2 Kings 23.10, Jeremiah 7.31-32, 19.6, 11-14). |

==Traditional accounts and theories== | ==Traditional accounts and theories== | ||

| − | + | ===Rabbinical Tradition=== | |

| − | + | [[File:Kircher oedipus aegyptiacus 27 moloch.png|thumb|400px|Moloch showing the seven compartments for different sacrifices, from Athanasius Kircher, ''Oedipus Aegyptiacus'', 1652]] | |

| − | + | The significance of Moloch was elaborated and speculated upon by numerous post-Biblical thinkers, Jewish and non-Jewish. The twelfth century, [[Rabbi]] [[Rashi]] stated that the cult of Moloch involved a father conceding his son to pagan priests, who then passed a child between two flaming pyres. Rashi, as well as other rabbinic commentators, interpreted human sacrifice to Moloch as being adulterous, as it solidified allegiance to a false god. Such interpretations in terms of idolatry made the biblical laws seem more pertinent in the twelfth century, as the prevalence of human sacrifice had long since tapered away. Commenting on [[Book of Jeremiah|Jeremiah]] 7.31, Rashi stated that Moloch: | |

| − | + | <blockquote>was made of brass; and they heated him from his lower parts; and his hands being stretched out, and made hot, they put the child between his hands, and it was burnt; when it vehemently cried out; but the priests beat a drum, that the father might not hear the voice of his son, and his heart might not be moved. </blockquote> | |

| − | + | Another rabbinical tradition says that the idol was hollow and divided into seven compartments, each of which contained a separate offering for the god. In the first compartment was flour, in the second turtle doves, in the third a ewe, in the fourth a ram, in the fifth a calf, in the sixth an ox, and in the seventh a child, all of which were burnt together by heating the statue inside. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

===Moloch in medieval texts=== | ===Moloch in medieval texts=== | ||

| − | |||

| − | It is likely that the motif of stealing children was inspired by the traditional understanding that babies were sacrificed to Moloch. | + | Like some other gods and demons found in the [[Bible]], Moloch appears as part of medieval [[demonology]], primarily as a Prince of [[Hell]]. This Moloch specializes in making mothers weep, as he takes particular pleasure in stealing their children. According to some sixteenth century demonologists, Moloch's power is stronger in October. It is likely that the motif of stealing children was inspired by the traditional understanding that babies were sacrificed to Moloch. Moloch was alternately conceived of in such accounts as a rebellious angel. |

| − | == | + | ==Moloch as a type of sacrifice== |

| + | ===Eissfeldt's Discovery=== | ||

| + | It was widely held that Moloch was a god until 1935 when Otto Eissfeldt, a German archaeologist, published a radical new theory based upon excavations he had made in [[Carthage]]. During these excavations he made several telling discoveries, most importantly that of a relief showing a priest holding a child, as well as a sanctuary to the [[goddess]] Tanit comprising a cemetery with thousands of burned bodies of animal and of human infants. He concluded that ''mlk'' in Hebrew was instead a term used to refer to a particular kind of sacrifice, rather than a specific god. Eissfeldt connected the Punic ''mlk'' and Moloch to a Syriac verb ''mlk'' meaning "to promise", leading to ''mlk'' ''(molk)'' as a Punic term for sacrifice, a theory also supported as "the least problematic solution" by Heath Dewrell.<ref> Heath D. Dewrell, ''Child Sacrifice in Ancient Israel'' (Eisenbrauns, 2017, ISBN 978-1575064949).</ref> This sacrifice, Eissfeldt claimed, involved humans in some cases. The abomination described in the Hebrew writings, then, occurred not in the worship a god Moloch who demanded that children be sacrificed to him, but rather in the practice of sacrificing human children as a ''molk.'' Hebrews were strongly opposed to sacrificing first-born children as a ''molk'' to Yahweh himself. Eissfeldt also speculated that the practice may also have been conducted by their neighbors in [[Canaan]]. | ||

| − | + | Eissfeldt's theory is supported by classical sources and archaeological evidence that suggest the Punic culture practiced [[human sacrifice]]. Thus, Eissfeldt identified the site as a ''tophet,'' using a Hebrew word of previously unknown meaning connected to the burning of human beings in some Biblical passages. Similar ''tophets'' have since been found at [[Carthage]] and other places in North Africa, as well as in [[Sardinia]], [[Malta]], and [[Sicily]]. Thus, a body of evidence exists in support of the theory that Moloch actually refers to the act of human sacrifice itself. | |

| − | == | + | ===Criticisms=== |

| − | ===Eissfeldt's theory | + | From the beginning there were those who doubted Eissfeldt's theory, though opposition was only sporadic until 1970. Prominent archaeologist Sabatino Moscati, who had at first accepted Eissfeldt's idea, changed his opinion and spoke against it. |

| − | |||

| − | + | The most common arguments against the theory were that classical accounts of the [[child sacrifice|sacrifices of children]] at [[Carthage]] were not numerous and were only described as occurring in times of peril, rather than being a regular occurrence. Critics also questioned whether the burned bodies of infants could be stillborn children or children who had died of natural causes. Burning of their bodies may have been a religious practice applied under such circumstances. Further, it was noted that many of the allegations of human sacrifices made against the Carthagians were controversial, and therefore accounts of such sacrifices were exaggerated or entirely false. Accusations of [[human sacrifice]] in Carthage had been found only among a small number of authors and were not mentioned at all by many other writers who dealt with Carthage in greater depth, and sometimes even among those who were more openly hostile to Carthage. | |

| − | + | Furthermore, the nature of what was sacrificed is not for certain. The children put to death are described in the classical accounts as boys and girls rather than infants exclusively. The Biblical decrying of the sacrificing of one's children as a ''molk'' sacrifice does not precisely indicate that all ''molk'' sacrifices must involve a human child sacrifice or even that a ''molk'' usually involved human sacrifice. Many texts referring to the ''molk'' sacrifice mentioned animals more often than humans. The term ''mlk'' is a versatile one and can also be combined with '''dm'' to mean "sacrifice of a man," while ''mlk 'mr'' refers to the "sacrifice of a sheep." Therefore the term ''mlk'' on its own is not specified. Thus, some scholars have concluded that ''mlk'' refers to the act of "offering" in general, rather than human sacrifice specifically. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | If Moloch were indeed a type of sacrifice and not a god, this would suggest that an improbable number of Biblical interpreters would have misunderstood the term, which is referred to in the sense of a god in numerous books of the Bible. Such a misunderstanding is unlikely considering the fact that Biblical writers wrote during, or in close proximity to, the time that such sacrifices were being practiced. For example, Day argued that Leviticus 20:5's mention of "whoring after Moloch" necessarily implied that Moloch was a god.<ref>John Day, ''Yahweh and the Gods and Goddesses of Canaan'' (Sheffield Academic Press, 2002, ISBN 978-0826468307).</ref> It is also highly unlikely that all other ancient versions of the Biblical texts would ubiquitously ignore the sacrificial definition of Moloch if the word indeed developed out of this meaning. Thus, there is little support of the supposition that the Moloch of the Old Testament should be equated with the Punic ''molk.'' | |

| − | + | Furthermore, Eissfeldt's use of the Biblical word ''tophet'' was criticized as arbitrary. Even those who believed in Eissfeldt's general theory mostly took ''tophet'' to mean something along the lines of “hearth” in the Biblical context, rather than a [[cemetery]] of some kind. With each of these criticisms considered, detractors to Eissfeldt's theories have steadily gained in numbers. | |

| − | + | ==Moloch in literature and popular culture== | |

| + | [[File:Museo nazionale del Cinema - Cabiria (Turin) crop.jpg|thumb|300px|Moloch statue from Giovanni Pastrone's film ''Cabiria'' (1914), National Museum of Cinema (Turin)]] | ||

| + | Throughout modernity, Moloch has appeared frequently in works of literature, art, and film. In [[John Milton|Milton]]'s classic ''Paradise Lost,'' Moloch is one of the greatest warriors of the rebel [[angels]], vengeful, militant, and: | ||

| − | + | :"besmeared with blood | |

| − | + | :Of human sacrifice, and parents' tears." | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | Milton lists Moloch among the chief of Satan's angels in Book I. Furthermore, Moloch orates before the parliament of hell in Book 2:43 -105, arguing for immediate warfare against [[God]]. The poem explains that he later becomes revered as a pagan god on earth. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | The | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | In [[ | + | In his successful 1888 novel about [[Carthage]] entitled ''Salammbô,'' French author Gustave Flaubert imaginatively created his own version of the Carthaginian religion, depicting known gods such as Ba‘al Hammon, Khamon, Melkarth and Tanith. He also included Moloch within this pantheon, and it was to Moloch that the Carthaginians offered children as sacrifices. Flaubert described Moloch mostly according to the rabbinic descriptions, though he made some additions of his own. Due to Flaubert's vivid descriptions of the god, images from ''Salammbô'' (and the subsequent silent film ''Cabiria'' released in 1914 which was largely based upon it) have actually come to influence some examples of scholarly writing about Moloch, Melqart, Carthage, Ba‘al Hammon, etc. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | He | ||

| − | + | Moloch also features prominently in the second part of the poem ''Howl,'' arguably [[Allen Ginsberg]]'s most recognizable work. In this poem, Moloch is interpreted as representative of American greed and bloodthirstiness, and Ginsberg parallels the smoke of the sacrificed humans to the pollution created by factories. In Alexandr Sokurov's 1999 film ''Moloch,'' Moloch is employed as a metaphor for [[Adolf Hitler]]. The figure of Moloch also appears frequently in popular culture, in a variety of media spanning movies to videogames. Modern Hebrew often uses the expression "sacrifice something to the Moloch" to refer to any harm undertaken for worthless causes. | |

| − | + | == Notes == | |

| + | <references/> | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | * | + | * Bergmann, Martin S. ''In the Shadow of Moloch''. Columbia University Press, 1992. ISBN 978-0231072489 |

| − | * Day, John | + | * Day, John. ''Molech: A God of Human Sacrifice in the Old Testament.'' New York: Cambridge University. 1989. ISBN 0521364744 |

| + | * Day, John. ''Yahweh and the Gods and Goddesses of Canaan''. Sheffield Academic Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0826468307 | ||

| + | * Dewrell, Heath D. ''Child Sacrifice in Ancient Israel''. Eisenbrauns, 2017. ISBN 978-1575064949 | ||

| + | * Grena, G.M. ''LMLK—A Mystery Belonging to the King vol. 1.'' Redondo Beach, CA: 4000 Years of Writing History, 2004. ISBN 097487860X | ||

| − | == | + | ==External links== |

| + | All links retrieved November 9, 2022. | ||

| − | *[ | + | * [https://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/10937-moloch-molech Moloch (Molech)] ''Jewish Encyclopedia'' |

| − | + | * [https://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/4345-chiun Chiun] ''Jewish Encyclopedia'' | |

| − | + | * [https://www.newadvent.org/cathen/10443b.htm Moloch] ''Catholic Encyclopedia'' | |

| − | + | * [https://www.deliriumsrealm.com/moloch/ Moloch] ''DeliriumsRealm'' | |

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

[[Category: Philosophy and religion]] | [[Category: Philosophy and religion]] | ||

Latest revision as of 21:06, 21 December 2022

Moloch (also rendered as Molech or Molekh, from the Hebrew מלך mlk) is a Canaanite god in the Old Testament associated with human sacrifice. Some scholars have suggested that the term refers to a particular kind of sacrifice carried out by the Phoenicians and their neighbors rather than a specific god, though this theory has been widely rejected. Although Moloch is referred to sparingly in the Old Testament, the significance of the god and the sacrificial ritual cannot be underestimated, as the Israelite writers vehemently reject the related practices, regarding them as murderous and idolatrous.

While no particular form of Moloch is known due to the ambiguity of his origin, he is usually depicted in the form of a calf or an ox, or else as a man with the head of a bull. The figure of Moloch has been an object of fascination over the centuries, and has been used to bolster metaphorical and thematic elements within numerous modern works of art, film, and literature.

Etymology

The Hebrew letters מלך (mlk) usually stand for melek or “the king,” and were used to refer to the status of the sacrificial god within his cult. Nineteenth and early twentieth century archaeology has found almost no physical evidence of a god referred to as Moloch or by any similar epithet. Thus, if such a god did exist, Moloch was not the name he was known by among his worshipers, but rather a Hebrew transliteration. The term usually appears in the Old Testament text as the compound lmlk. The Hebrew preposition l- means “to,” but it can often mean “for” or “as a(n).” Accordingly, one can translate lmlk as "to Moloch," "for Moloch," "as a Moloch," "to the Moloch," "for the Moloch" or "as the Moloch." We also find hmlk, “the Moloch” standing by itself on one occasion. The written form Moloch (in the Septuagint Greek translation of the Old Testament), or Molech (Hebrew), is no different than the word Melek or “king,” which is purposely improperly vocalized by interposing the vowels of the Hebrew term bosheth or “shameful thing.” This distortion allows the term to express the compunction felt by Israelites who witnessed their brethren worshiping this god of human sacrifices, and in doing so prevents them from giving noble status of "king" to what was for all intents and purposes, a false idol.

Moloch and other gods

A variety of scholars have suggested that Moloch is not an original god himself, but actually an alternative epithet given to another god or gods from cultures who lived in proximity to the Israelites. For instance, some scholars hold that Moloch is actually the Ammonite god Milcom, due to the phonological similarity of the names. While the names are indeed similar, the Old Testament text clearly differentiates between these deities on several occasions, most notably when referring to the national god of the Ammonites as Milcom and the god of human sacrifice as Moloch (1 Kings 11.33; Zephaniah 1.5). Further, the Old Testament mostly refers to Molech as Canaanite, rather than Ammonite. The Septuagint refers to Milcom in 1 Kings 11.7 when referring to Solomon's religious failings, instead of Moloch, which may have resulted from a scribal error in the Hebrew. Many English translations accordingly follow the non-Hebrew versions at this point and render Milcom.

Other scholars have claimed that Moloch is merely another name for Ba'al, the Sacred Bull who was widely worshiped in the ancient Near East. Ba'al is also frequently mentioned in the Old Testament, sometimes even in proximity to Moloch. Jeremiah 32.35, for instance, refers to rituals dedicated to Ba'al in the Hinnom Valley, with the offering of child sacrifices to Moloch. Allusions made to Moloch in the context of the Canaanite fertility cult, which was headed by Ba'al, also suggest a close relationship between the two figures. Further, the Bible commonly makes reference to burnt offerings being given to Ba’al himself. While these examples could be interpreted to suggest that Moloch and Ba’al are the same god, they more likely refer to the acknowledgement of their close relationship. Again, given the fact that a distinct name is used in the context of sacrifice suggests that Moloch can only be related to Ba'al (perhaps in the faculty of a henotheistic underling) rather than equated with him.

The fact that the name of Moloch appeared frequently in ancient sources suggests that Moloch was viewed as a distinct deity. John Day, in his book Molech: A God of Human Sacrifice in the Old Testament claims that there was indeed a Canaanite god whose name was rendered Melek in the Old Testament. Day cites evidence of this god from the Ugraritic texts, which are serpent charms, where he appears as Malik. Malik, he claims, is equivalent to Nergal, the Mesopotamian god of the underworld who is listed upon god lists from ancient Babylonia. Day concludes that this evidence is consistent with Moloch's malevolent status in the Old Testament, described in Isaiah 57.9 where the prophet parallels sacrifice to Moloch with a journey into the underground world of Sheol. A god of the underworld is just the kind of god one might worship in the valley of Ben-Hinnom rather than on a hill top.

Old Testament

Moloch has been most often characterized in the Old Testament by the phrase "to cause to pass through the fire," (h'byrb's in Hebrew) as is used in 2 Kings 23.10. Although this term does not specify on its own whether the ritual related to Moloch involves human sacrifice, the Old Testament clearly interprets it to be so. For example, Isaiah 57.5 states:

You who burn with lust among the oaks, under every luxuriant tree; who slay your children in the valleys, under the clefts of rocks.

Four verses later, Moloch is mentioned specifically:

You journeyed to Moloch with oil and multiplied your perfumes; you sent your envoys far off, and sent down even to Sheol. (Isaiah 57.9)

This reference to the underworld suggests that the fate of children is to be sent to death at the hands of Moloch. Thus, although Moloch's role in the Old Testament is small, it is nonetheless important, as his worship most clearly illustrates the more brutal aspects of idolatry and therefore reinforces the second commandment. Leviticus 18.21 reads:

And you shall not let any of your seed pass through Mo'lech, neither shall you profane the name of your God: I am the Lord.

Leviticus 20.2-5 deals with Moloch at length and promises a punishment of death by stoning for perpetration of human sacrifices:

Whoever he be of the Sons of Israel or of the strangers that sojourn in Israel, that gives any of his seed Mo'lech; he shall surely be put to death: the people of the land shall stone him with stones. And I will set my face against that man and will cut him off from among his people; because he has given of his seed Mo'lech, to defile my sanctuary, and to profane my holy name. And if the people of the land do at all hide their eyes from that man, when he gives of his seed Mo'lech, and do not kill him, then I will set my face against that man, and against his family, and will cut him off, and all that go astray after him, whoring after Mo'lech from among the people.

Here it becomes evident that it is not only worship of Moloch that is a transgression; failure to identify and punish worshipers of Moloch is also considered to be a grave sin. Also, the metaphor of prostitution is used in order to convey the sense of spiritual adultery which is being committed against God, or Yahweh, through the worship of Moloch.

These passages suggest that disdain for Moloch arose due to his worship “alongside” Yahweh, thereby affirming an idolatrous multiplicity of gods. Alternately, Moloch's worship may have been forbidden based on the fact that he was actually “equated” with Yahweh. The prose sections of Jeremiah suggest that there were some worshipers of Moloch who thought Yahweh had commanded the offerings to Moloch based upon the sacrifices of the first born which are mentioned in the Pentateuch (for instance, Exodus 22.28). Jeremiah 32.35 reads:

And they built the high places of the Ba‘al, which are in the valley of Ben-hinnom, to cause their sons and their daughters to pass through the fire Mo'lech; which I did not command them, nor did it come into my mind that they should do this abomination, to cause Judah to sin.

This wording suggests that the Israelites may have erroneously developed the idea that Yahweh had decreed such sacrifices to Moloch. This theory is questionable, however, as sacrifices to Moloch were undertaken away from the temple in the valley of Hinnom, in a place commonly referred to as Tophet (as mentioned in 2 Kings 23.10, Jeremiah 7.31-32, 19.6, 11-14).

Traditional accounts and theories

Rabbinical Tradition

The significance of Moloch was elaborated and speculated upon by numerous post-Biblical thinkers, Jewish and non-Jewish. The twelfth century, Rabbi Rashi stated that the cult of Moloch involved a father conceding his son to pagan priests, who then passed a child between two flaming pyres. Rashi, as well as other rabbinic commentators, interpreted human sacrifice to Moloch as being adulterous, as it solidified allegiance to a false god. Such interpretations in terms of idolatry made the biblical laws seem more pertinent in the twelfth century, as the prevalence of human sacrifice had long since tapered away. Commenting on Jeremiah 7.31, Rashi stated that Moloch:

was made of brass; and they heated him from his lower parts; and his hands being stretched out, and made hot, they put the child between his hands, and it was burnt; when it vehemently cried out; but the priests beat a drum, that the father might not hear the voice of his son, and his heart might not be moved.

Another rabbinical tradition says that the idol was hollow and divided into seven compartments, each of which contained a separate offering for the god. In the first compartment was flour, in the second turtle doves, in the third a ewe, in the fourth a ram, in the fifth a calf, in the sixth an ox, and in the seventh a child, all of which were burnt together by heating the statue inside.

Moloch in medieval texts

Like some other gods and demons found in the Bible, Moloch appears as part of medieval demonology, primarily as a Prince of Hell. This Moloch specializes in making mothers weep, as he takes particular pleasure in stealing their children. According to some sixteenth century demonologists, Moloch's power is stronger in October. It is likely that the motif of stealing children was inspired by the traditional understanding that babies were sacrificed to Moloch. Moloch was alternately conceived of in such accounts as a rebellious angel.

Moloch as a type of sacrifice

Eissfeldt's Discovery

It was widely held that Moloch was a god until 1935 when Otto Eissfeldt, a German archaeologist, published a radical new theory based upon excavations he had made in Carthage. During these excavations he made several telling discoveries, most importantly that of a relief showing a priest holding a child, as well as a sanctuary to the goddess Tanit comprising a cemetery with thousands of burned bodies of animal and of human infants. He concluded that mlk in Hebrew was instead a term used to refer to a particular kind of sacrifice, rather than a specific god. Eissfeldt connected the Punic mlk and Moloch to a Syriac verb mlk meaning "to promise", leading to mlk (molk) as a Punic term for sacrifice, a theory also supported as "the least problematic solution" by Heath Dewrell.[1] This sacrifice, Eissfeldt claimed, involved humans in some cases. The abomination described in the Hebrew writings, then, occurred not in the worship a god Moloch who demanded that children be sacrificed to him, but rather in the practice of sacrificing human children as a molk. Hebrews were strongly opposed to sacrificing first-born children as a molk to Yahweh himself. Eissfeldt also speculated that the practice may also have been conducted by their neighbors in Canaan.

Eissfeldt's theory is supported by classical sources and archaeological evidence that suggest the Punic culture practiced human sacrifice. Thus, Eissfeldt identified the site as a tophet, using a Hebrew word of previously unknown meaning connected to the burning of human beings in some Biblical passages. Similar tophets have since been found at Carthage and other places in North Africa, as well as in Sardinia, Malta, and Sicily. Thus, a body of evidence exists in support of the theory that Moloch actually refers to the act of human sacrifice itself.

Criticisms

From the beginning there were those who doubted Eissfeldt's theory, though opposition was only sporadic until 1970. Prominent archaeologist Sabatino Moscati, who had at first accepted Eissfeldt's idea, changed his opinion and spoke against it.

The most common arguments against the theory were that classical accounts of the sacrifices of children at Carthage were not numerous and were only described as occurring in times of peril, rather than being a regular occurrence. Critics also questioned whether the burned bodies of infants could be stillborn children or children who had died of natural causes. Burning of their bodies may have been a religious practice applied under such circumstances. Further, it was noted that many of the allegations of human sacrifices made against the Carthagians were controversial, and therefore accounts of such sacrifices were exaggerated or entirely false. Accusations of human sacrifice in Carthage had been found only among a small number of authors and were not mentioned at all by many other writers who dealt with Carthage in greater depth, and sometimes even among those who were more openly hostile to Carthage.

Furthermore, the nature of what was sacrificed is not for certain. The children put to death are described in the classical accounts as boys and girls rather than infants exclusively. The Biblical decrying of the sacrificing of one's children as a molk sacrifice does not precisely indicate that all molk sacrifices must involve a human child sacrifice or even that a molk usually involved human sacrifice. Many texts referring to the molk sacrifice mentioned animals more often than humans. The term mlk is a versatile one and can also be combined with 'dm to mean "sacrifice of a man," while mlk 'mr refers to the "sacrifice of a sheep." Therefore the term mlk on its own is not specified. Thus, some scholars have concluded that mlk refers to the act of "offering" in general, rather than human sacrifice specifically.

If Moloch were indeed a type of sacrifice and not a god, this would suggest that an improbable number of Biblical interpreters would have misunderstood the term, which is referred to in the sense of a god in numerous books of the Bible. Such a misunderstanding is unlikely considering the fact that Biblical writers wrote during, or in close proximity to, the time that such sacrifices were being practiced. For example, Day argued that Leviticus 20:5's mention of "whoring after Moloch" necessarily implied that Moloch was a god.[2] It is also highly unlikely that all other ancient versions of the Biblical texts would ubiquitously ignore the sacrificial definition of Moloch if the word indeed developed out of this meaning. Thus, there is little support of the supposition that the Moloch of the Old Testament should be equated with the Punic molk.

Furthermore, Eissfeldt's use of the Biblical word tophet was criticized as arbitrary. Even those who believed in Eissfeldt's general theory mostly took tophet to mean something along the lines of “hearth” in the Biblical context, rather than a cemetery of some kind. With each of these criticisms considered, detractors to Eissfeldt's theories have steadily gained in numbers.

Moloch in literature and popular culture

Throughout modernity, Moloch has appeared frequently in works of literature, art, and film. In Milton's classic Paradise Lost, Moloch is one of the greatest warriors of the rebel angels, vengeful, militant, and:

- "besmeared with blood

- Of human sacrifice, and parents' tears."

Milton lists Moloch among the chief of Satan's angels in Book I. Furthermore, Moloch orates before the parliament of hell in Book 2:43 -105, arguing for immediate warfare against God. The poem explains that he later becomes revered as a pagan god on earth.

In his successful 1888 novel about Carthage entitled Salammbô, French author Gustave Flaubert imaginatively created his own version of the Carthaginian religion, depicting known gods such as Ba‘al Hammon, Khamon, Melkarth and Tanith. He also included Moloch within this pantheon, and it was to Moloch that the Carthaginians offered children as sacrifices. Flaubert described Moloch mostly according to the rabbinic descriptions, though he made some additions of his own. Due to Flaubert's vivid descriptions of the god, images from Salammbô (and the subsequent silent film Cabiria released in 1914 which was largely based upon it) have actually come to influence some examples of scholarly writing about Moloch, Melqart, Carthage, Ba‘al Hammon, etc.

Moloch also features prominently in the second part of the poem Howl, arguably Allen Ginsberg's most recognizable work. In this poem, Moloch is interpreted as representative of American greed and bloodthirstiness, and Ginsberg parallels the smoke of the sacrificed humans to the pollution created by factories. In Alexandr Sokurov's 1999 film Moloch, Moloch is employed as a metaphor for Adolf Hitler. The figure of Moloch also appears frequently in popular culture, in a variety of media spanning movies to videogames. Modern Hebrew often uses the expression "sacrifice something to the Moloch" to refer to any harm undertaken for worthless causes.

Notes

- ↑ Heath D. Dewrell, Child Sacrifice in Ancient Israel (Eisenbrauns, 2017, ISBN 978-1575064949).

- ↑ John Day, Yahweh and the Gods and Goddesses of Canaan (Sheffield Academic Press, 2002, ISBN 978-0826468307).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bergmann, Martin S. In the Shadow of Moloch. Columbia University Press, 1992. ISBN 978-0231072489

- Day, John. Molech: A God of Human Sacrifice in the Old Testament. New York: Cambridge University. 1989. ISBN 0521364744

- Day, John. Yahweh and the Gods and Goddesses of Canaan. Sheffield Academic Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0826468307

- Dewrell, Heath D. Child Sacrifice in Ancient Israel. Eisenbrauns, 2017. ISBN 978-1575064949

- Grena, G.M. LMLK—A Mystery Belonging to the King vol. 1. Redondo Beach, CA: 4000 Years of Writing History, 2004. ISBN 097487860X

External links

All links retrieved November 9, 2022.

- Moloch (Molech) Jewish Encyclopedia

- Chiun Jewish Encyclopedia

- Moloch Catholic Encyclopedia

- Moloch DeliriumsRealm

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.