Mogao Caves

Coordinates:

| Mogao Caves* | |

|---|---|

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| |

| State Party | |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, ii, iii, iv, v, vi |

| Reference | 440 |

| Region** | Asia-Pacific |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 1987 (11th Session) |

| * Name as inscribed on World Heritage List. ** Region as classified by UNESCO. | |

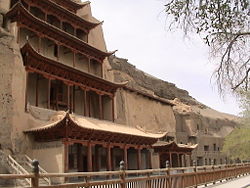

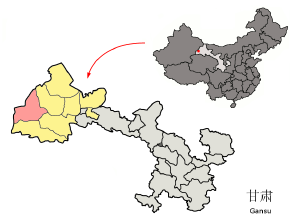

The Mogao Caves, or Mogao Grottoes (Chinese: 莫高窟; pinyin: mò gāo kū) (also known as the Caves of the Thousand Buddhas and Dunhuang Caves) forms a system of 492 temples 25 kilometers (15.5 miles) southeast of the center of Dunhuang, an oasis strategically located at a religious and cultural crossroads on the Silk Road, in Gansu province, China. The caves contain some of the finest examples of Buddhist art spanning a period of 1,000 years.[1] Construction of the Buddhist cave shrines began in 366 C.E. as places to store scriptures and art.[2] The Mogao Caves have become the best known of the Chinese Buddhist grottoes and, along with Longmen Grottoes and Yungang Grottoes, one of the three famous ancient sculptural sites of China. The Mogao Caves became one of the UNESCO World Heritage Sites in 1987.[1]

As a depository of pivotal Buddhist, Taoist, and Christian documents, the Mogao Caves provided a rare opportunity for Buddhist monks and devotees to study those doctrines. In that regard, the caves served as a virtual melting pot of Christian, Buddhist, Taoist, and even Hindu ideas in China. The discovery of the caves that served as a depository of documents from those faiths, sealed from the eleventh century, testify to the interplay of religions. The Diamond Sutra and the Jesus Sutras stand out among the scriptural treasures found in the caves in the twentieth century.

History

According to local legend, in 366 C.E. a Buddhist monk, Lè Zūn (樂尊), had a vision of a thousand Buddhas and inspired the excavation of the caves he envisioned. The number of temples eventually grew to more than a thousand.[3] As Buddhist monks valued austerity in life, they sought retreat in remote caves to further their quest for enlightenment. From the fourth until the fourteenth century, Buddhist monks at Dunhuang collected scriptures from the west while many pilgrims passing through the area painted murals inside the caves. The cave paintings and architecture served as aids to meditation, as visual representations of the quest for enlightenment, as mnemonic devices, and as teaching tools to inform illiterate Chinese about Buddhist beliefs and stories.

The murals cover 450,000 square feet (42,000 m²). The caves had been walled off sometime after the 11th century after they had become a repository for venerable, damaged and used manuscripts and hallowed paraphernalia.[4] The following, quoted from Fujieda Akira, has been suggested:

The most probable reason for such a huge accumulation of waste is that, when the printing of books became widespread in the tenth century, the handwritten manuscripts of the Tripitaka at the monastic libraries must have been replaced by books of a new type—the printed Tripitaka. Consequently, the discarded manuscripts found their way to the sacred waste-pile, where torn scrolls from old times as well as the bulk of manuscripts in Tibetan had been stored. All we can say for certain is that he came from the Wu family, because the compound of the three-storied cave temples, Nos. 16-18 and 365-6, is known to have been built and kept by the Wu family, of which the mid-ninth century Bishop of Tun-Huan, Hung-pien, was a member. [5]

In the early 1900s, a Chinese Taoist named Wang Yuanlu appointed himself guardian of some of those temples. Wang discovered a walled up area behind one side of a corridor leading to a main cave. Behind the wall stood a small cave stuffed with an enormous hoard of manuscripts dating from 406 to 1002 C.E. Those included old Chinese hemp paper scrolls, old Tibetan scrolls, paintings on hemp, silk or paper, numerous damaged figurines of Buddhas, and other Buddhist paraphernalia.

The subject matter in the scrolls covers diverse material. Along with the expected Buddhist canonical works numbered original commentaries, apocryphal works, workbooks, books of prayers, Confucian works, Taoist works, Nestorian Christian works, works from the Chinese government, administrative documents, anthologies, glossaries, dictionaries, and calligraphic exercises. The majority of which he sold to Aurel Stein for the paltry sum of 220 pounds, a deed which made him notorious to this day in the minds of many Chinese. Rumors of that discovery brought several European expeditions to the area by 1910.

Those included a joint British/Indian group led by Aurel Stein (who took hundreds of copies of the Diamond Sutra because he lacked the ability to read Chinese), a French expedition under Paul Pelliot, a Japanese expedition under Otani Kozui, and a Russian expedition under Sergei F. Oldenburg which found the least. Pelloit displayed interest in the more unusual and exotic of Wang's manuscripts such as those dealing with the administration and financing of the monastery and associated lay men's groups. Those manuscripts survived only because they formed a type of palimpsest in which the Buddhist texts (the target of the preservation effort) had been written on the opposite side of the paper. The Chinese government ordered the remaining Chinese manuscripts sent to Peking (Beijing). The mass of Tibetan manuscripts remained at the sites. Wang embarked on an ambitious refurbishment of the temples, funded in part by solicited donations from neighboring towns and in part by donations from Stein and Pelliot.[4] The image of the Chinese astronomy Dunhuang map is one of the many important artifact found on the scrolls. Today, the site continues the subject of an ongoing archaeological project.[6]

Diamond Sutra

|

History of Buddhism | |

|

Timeline of Buddhism | |

|

Foundations | |

|

Four Noble Truths | |

|

Key Concepts | |

|

Three marks of existence | |

|

Major Figures | |

|

Gautama Buddha | |

|

Practices and Attainment | |

|

Buddhahood · Bodhisattva | |

|

Regions | |

|

Southeast Asia · East Asia | |

|

Branches | |

|

Theravāda · Mahāyāna | |

|

Texts | |

|

Pali Canon · Mahayana Sutras | |

|

Comparative Studies | |

The Diamond Sutra numbered among the manuscripts found in the Mogao Caves. The Diamond Sutra (Sanskrit: वज्रच्छेदिका प्रज्ञापारमितासूत्र Vajracchedikā-prajñāpāramitā-sūtra; Chinese: 金剛般若波羅蜜多經 or short 金剛經, pinyin: jīngāng bōrě bōluómìduō jīng or jīngāng jīng; Japanese: kongou hannya haramita kyou or short kongou kyou; Korean: 금강반야바라밀경 (金剛般若波羅蜜經), or 금강경 (金剛經) for short; Vietnamese Kim cương bát-nhã-ba-la-mật-đa kinh or Kim cương kinh; Tibetan (Wylie): ’Phags pa shes rab kyi pha rol tu phyin pa rdo rje gcod pa zhes bya ba theg pa chen po’i mdo; "The Sutra of the Perfection of Wisdom of the Diamond that Cuts Through Illusion" constitutes a short Mahayana sutra of the Perfection of Wisdom genre, which teaches the practice of the avoidance of abiding in extremes of mental attachment. The copy of the Diamond Sutra, found sealed in Mogao Caves in the early 20th century, represents the oldest known printed book, with a date of 868 C.E.

Contents

The Diamond Sutra, like many sutras, begins with the famous phrase: "Thus have I heard" (एवं मया श्रुतम्, evaṃ mayā śrutam). In this sutra, the Buddha has finished his daily walk with the monks to gather offerings of food and sits down to rest. One of the more senior monks, Subhuti, comes forth and asks the Buddha a question. A lengthy, often repetitive, dialog regarding the nature of perception proceeds. The Buddha often uses paradoxical phrases like: "What is called the highest teaching is not the highest teaching".[7]

The Buddha tried to help Subhuti unlearn his preconceived, and limited, notions of reality, the nature of Enlightenment, and compassion. A particularly noteworthy part takes place when the Buddha teaches Subhuti that the Bodhisattva's lack of pride in his work to save others, and his lack of calculated or contrived compassion, makes a Bodhisattva great. The Bodhisattva practices sincere compassion that comes from deep within, without any sense of ego or gain.

In another section, Subhuti expresses concern that the Diamond Sutra will disappear 500 years later (alternatively, during the last 500 years of that era). The Buddha assures Subhuti that well after he passes, some will live who can grasp the meaning of the Diamond Sutra and put it into practice. That section seems to reflect a concern found in other Buddhist texts that the teachings of the Buddha would eventually fade and become corrupted. A popular Buddhist concept, known as mappo in Japanese, also reflects that same anxiety.

In Practice

Since the Diamond Sutra can be read in approximately forty minutes, devotees often memorize and chant it in Buddhist monasteries. The sutra has retained popularity in the Mahāyāna Buddhist tradition for over a millennium, especially in East Asia, and most importantly within the East Asian meditation (Zen/Chan/Seon/Thien) tradition. Practitioners recite, teach, and comment upon it extensively. The text resonates with a core aspect of Chan doctrine/praxis; the theme of "non-abiding."

The statement occurs repeatedly in the Diamond Sutra that if a person embodies even four lines of the Sutra within their sadhana, they will be blessed. Toward the end of the sutra a gatha translates as follows (borrowing to some extent from both Thich Nhat Hanh and Mu Soeng): "Thus should one view all of the fleeting world - a drop of dew, a bubble in a stream, a flash of lightning in a summer cloud, a star at dawn, a phantom, and a dream."[8]

Mogao Caves Copy in British Museum

The wood block printed copy taken from Mogao Caves sits in the British Library. Although earlier copies exist, the Mogao Caves copy represents the earliest example which bears an actual date. Archaeologist Sir Marc Aurel Stein purchased the scroll, which measures about sixteen feet long, in 1907 from Abbot Wang who took care of the caves known as the "Caves of the Thousand Buddhas."

The book displays a great maturity of design and layout and speaks of a considerable ancestry for woodblock printing. The colophon, at the inner end, reads: Reverently [caused to be] made for universal free distribution by Wang Jie on behalf of his two parents on the 13th of the 4th moon of the 9th year of Xiantong (i.e. 11th May, CE 868). That printing took place about 587 years before the printing of the Gutenberg Bible.

Jesus Sutras

Alopen, a Nestorian bishop of the Assyrian Church of the East, wrote the Jesus Sutras, or the Lost Sutras of Jesus during the seventh century. Archaeologist Sir Marc Aurel Stein purchased the scroll in 1907 from Abbot Wang. The Jesus Sutras, early Chinese language manuscripts of Christian teachings brought to China, date from between 635 C.E., the year of Christianity's introduction to China and 1005 C.E., when the Mogao Cave, near Dunhuang, had been sealed. Private collectors in Japan have three copies of the sutra, while a collector in Paris has another. Their language and content reflect varying levels of adaptation to Chinese culture, including Buddhist and Taoist influences.

List of sutras

The following list uses the numbering and nomenclature of Martin Palmer, an English scholar, author, and translator of Chinese religious texts.[9] The first title represents a poetic rendering while the title in parentheses represents a strict translation of the original Chinese.

Doctrinal sutras

- Sutra of the Teachings of the World-Honored One (Lokajvesta Teaching on Charity, Part Three)(一神(天)論(世尊布施論第三)?). Translated 641 C.E. Based on Tatian's Teachings of the Apostles or Diatessaron, a second-century gospel harmony written in Syriac.

- Sutra of Cause, Effect, and Salvation (First Treatise on the Oneness of Heaven)(一神(天)論( 一天論第一)?). Palmer sees a similarity with the Buddhist Milinda Panha, the Questions of King Milinda.

- Sutra of the Teachings of the World-Honored One (Sutra of the Origins, Second Part of the Teaching) (大秦景教宣元(至)本經?)

- Sutra of Jesus Christ.(序聽迷詩所(訶)經/救世主彌賽亞經?) Translated around 645. Refers to karma and reincarnation. Palmer conjectures influence from Tibet, Hinduism, and/or Jainism.

Liturgical sutras

- Da Qin Liturgy of Taking Refuge in the Three(大秦景教三威蒙度贊?). Translated 720 C.E.

- Let Us Praise (Invocation of the Dharma Kings and Sacred Sutras)(大秦景教大聖通真歸法贊?)

- The Sutra of Returning to Your Original Nature.(志玄安樂經?) Translated c. 780–790

The Xi'an Stele

The Xi'an Stele, composed in 781 in honor of a construction project at the Da Qin Pagoda, has recently been judged a Christian monastery at the time ("Da Qin" is the Chinese term for the Roman Empire). The Da Qin Pagoda stands near Lou Guan Tai, the traditional site of Lao Tze's composition of the Tao Te Ching. The stele, unearthed in 1625, stands on display in Xi'an, the nearest major city to the site.

Sutra

Sutra (literally "binding thread") designates a Sanskrit term referring to an aphorism or group of aphorisms. Originally applied to Hindu philosophy, and later to Buddhist canon scripture, the term applies indirectly in the case of the Jesus Sutras. In Chinese, all religious and classical books have the designator jing (經), including indigenous Chinese works, Buddhist scriptures. Works foreign to China, such as the Bible and the Koran, also have jing (經) appended. In the context of Buddhist scriptures, jing conventionally translates as "sutra." The Jesus Sutras, although uncanonical, commingle Christian philosophy with Buddhist and Taoist thought.

Gallery

A close-up of the fresco describing Emperor Han Wudi (156 – 87 B.C.E.) worshiping two statues of the Buddha, c. 700 C.E.

See also

- Chinese Buddhism

- Gansu

- Wood Block Printing

- Silk Road

- Han Dynasty

- Buddhist Art

- Tao-te Ching

Footnotes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Mogao Caves. UNESCO. Retrieved 2008-07-21.

- ↑ Silk Road - DunHuang (Tun-Huang) Grottoes. Retrieved 2008-07-21.

- ↑ Dunhuang—Mogao Caves—. Retrieved 2008-07-21.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Chinese Exploration and Excavations in Chinese Central Asia. International Dunhuang Project. Retrieved 2008-07-21.

- ↑ Leif Littrup. 1988. Analecta Hafniensia: 25 years of East Asian studies in Copenhagen (London: Curzon Press), p. 112.

- ↑ The International Dunhuang Project. Retrieved 2008-07-21.

- ↑ Diamond Sutra, Sec. 8, Subsec. 5 金剛經,依法出生分第八,五:結歸離相

- ↑ Soeng Mu, Diamond Sutra, and Thich Nhat Hanh, The diamond"

- ↑ Palmer and Eva Wong, The Jesus sutras

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Akira, Fujieda, "The Tun-Huan Manuscripts," in 'Leslie, Donald, Colin Mackerras, Gungwu Wang, and C. P. Fitzgerald. 1973. Essays on the sources for Chinese history. Canberra: Australian National University Press. ISBN 9780708103982.

- Baumer, Christoph. 2006. The church of the East: an illustrated history of Assyrian Christianity. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 9781845111151.

- Hopkirk, Peter. 1980. Foreign devils on the Silk Road: the search for the lost cities and treasures of Chinese Central Asia. London: Murray. ISBN 9780719537387.

- Littrup, Leif. 1988. Analecta Hafniensia: 25 years of East Asian studies in Copenhagen. London: Curzon Press. ISBN 9780700701995.

- Moule, A. C. 1930. Christians in China before the year 1550. London: S.P.C.K. OCLC 181797710.

- Mu, Soeng. 2000. Diamond Sutra: transforming the way we perceive the world. Boston, Mass: Wisdom Publications. ISBN 9780861711604.

- Nhat Hanh, Thich. 1992. The diamond that cuts through illusion: commentaries on the Prajñaparamita Diamond Sutra. Berkeley, Calif: Parallax Press. ISBN 9780938077510.

- Palmer, Martin, and Eva Wong. 2001. The Jesus sutras: rediscovering the lost scrolls of Taoist Christianity. New York: Ballantine. (Texts translated by Palmer, Eva Wong, and L. Rong Rong). ISBN 9780345434241.

- Riegert, Ray, and Thomas Moore. 2003. The lost sutras of Jesus: unlocking the ancient wisdom of the Xian Christian monks. Berkeley, Calif: Seastone. (Texts translated by John Babcock). ISBN 9781569753606.The

- Saeki, P. Yoshio. 1951. Nestorian documents and relics in China. Tokyo: Maruzen. (Contains the Chinese texts with English translations). OCLC 52011545.

- Tang, Li. 2004. A study of the history of Nestorian Christianity in China and its literature in Chinese: together with a new English translation of the Dunhuang Nestorian documents. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang. (A fresh scholarly translation by a Chinese academic, with historical background and critical linguistic commentary on the texts.). ISBN 9783631522745.

External links

- UNESCO Mogao Caves Site. Retrieved July 21, 2008.

- DunHuang [Tun-Huang Grottoes]. Retrieved July 21, 2008.

- International Dunhuang Project. Retrieved July 21, 2008.

- Turn the pages of the British Library's copy of the Diamond Sutra.. Retrieved July 23, 2008.

- Diamond Sutra: English Translation, by A. F. Price and Wong Mou-Lam. Retrieved July 23, 2008.

- Diamond Sutra - images of the original printed edition. Retrieved July 23, 2008.

- Core Teachings of Diamond Sutra with visual art by Fernando Casas. Retrieved July 23, 2008.

- The original texts of the Jesus Sutras in the Taisho Tripitaka: 序聽迷詩所經. Retrieved July 23, 2008. & 景教三威蒙度讚. Retrieved July 23, 2008.

- Did Christianity Reach China In the First Century?. Retrieved July 23, 2008.

| |||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.