Difference between revisions of "Lymphoma" - New World Encyclopedia

Rick Swarts (talk | contribs) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (9 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Approved}}{{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Paid}}{{Copyedited}} |

{{Infobox_Disease | | {{Infobox_Disease | | ||

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | '''Lymphoma''' is any of a diverse group of [[cancer]]s that originate in [[lymphocyte]]s of the [[lymphatic system]], a secondary (but open) circulatory system in [[vertebrate]]s. | + | '''Lymphoma''' is any of a diverse group of [[cancer]]s that originate in [[lymphocyte]]s of the [[lymphatic system]], a secondary (but open) circulatory system in [[vertebrate]]s. |

In lymphoma, the [[cell (biology)|cells]] in the lymphatic system grow abnormally, dividing too rapidly and growing without any order or control (Longe 2005). As a result, too much [[tissue]] develops and tumors are formed. Since lymph is widely distributed in the body, with twice as much lymph as blood and twice as many lymph vessels as blood vessels, the cancer may occur in many areas, such as the [[liver]], [[spleen]], and [[bone marrow]]. | In lymphoma, the [[cell (biology)|cells]] in the lymphatic system grow abnormally, dividing too rapidly and growing without any order or control (Longe 2005). As a result, too much [[tissue]] develops and tumors are formed. Since lymph is widely distributed in the body, with twice as much lymph as blood and twice as many lymph vessels as blood vessels, the cancer may occur in many areas, such as the [[liver]], [[spleen]], and [[bone marrow]]. | ||

| − | + | The lymphatic system plays a crucial role in maintaining homeostasis as well as good health. Lemole (2001) claims that the key to health is a healthy lymphatic system, specifically stating "you can eliminate 70 percent of the chronic illnesses that are in part the result of that system being clogged." Among measures recommended for a healthy lymphatic system are exercise, reduction of [[stress (medicine)|stress]], massages, and a healthy diet. | |

| + | Lymphoma represents a breakdown in the intricate coordination of the lymphatic system. Ironically, the lymphatic system is fundamentally important for combating cancer cells—as well as foreign bodies, such as [[virus]]es and [[bacteria]], and combating heart disease and arthritis as well. It is those cancers that originate in the lymphatic system that are referred to as lymphomas. But cancers can also originate outside the lymphatic system and then make their way into lymphoid tissues and glands. | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

There are many types of lymphoma. Lymphomas are part of the broad group of diseases called [[Hematological malignancy|hematological neoplasms]]. | There are many types of lymphoma. Lymphomas are part of the broad group of diseases called [[Hematological malignancy|hematological neoplasms]]. | ||

| − | Lymphoma commonly is categorized broadly as [[Hodgkin's lymphoma]] (HL) and [[Non-Hodgkin lymphoma|non-Hodgkin lymphoma]] (NHL, all other types of lymphoma). These are distinguished by cell type (Longe 2005). Scientific classification of the types of lymphoma is more detailed. In the | + | Lymphoma commonly is categorized broadly as [[Hodgkin's lymphoma]] (HL) and [[Non-Hodgkin lymphoma|non-Hodgkin lymphoma]] (NHL, all other types of lymphoma). These are distinguished by cell type (Longe 2005). Scientific classification of the types of lymphoma is more detailed. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the affliction was called simply Hodgkin's Disease, as it was discovered by Thomas Hodgkin in 1832. |

==Prevalence== | ==Prevalence== | ||

| Line 36: | Line 38: | ||

The '''WHO Classification''', published by the [[World Health Organization]] in 2001, is the latest classification of lymphoma (Sarkin 2001). It was based upon the "Revised European-American Lymphoma classification" (REAL). | The '''WHO Classification''', published by the [[World Health Organization]] in 2001, is the latest classification of lymphoma (Sarkin 2001). It was based upon the "Revised European-American Lymphoma classification" (REAL). | ||

| − | This classification attempts to classify lymphomas by cell type | + | This classification attempts to classify lymphomas by cell type (i.e. the normal cell type that most closely resembles the tumor). They are classified in three large groups: [[B cell]] tumors; [[T cell]] and [[natural killer cell]] tumors; [[Hodgkin lymphoma]], as well as other minor groups. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | B cells are [[lymphocyte]]s (a class of [[white blood cell]]s) that play a large role in the [[immune system#Adaptive immune system|adaptive immune system]] by making [[antibody|antibodies]] to identify and neutralize invading pathogens like [[bacteria]] and [[virus]]es. Specially, B cells play the major role in the [[humoral immunity|humoral immune response]], as opposed to the [[cell-mediated immunity|cell-mediated immune response]] that is governed by [[T cell]]s, another type of lymphocyte. T cells can be distinguished from B cells and natural killer (NK) cells by the presence of a special receptor on their cell surface that is called the T cell receptor (TCR). Lymphocyte-like natural killer (NK) cells also are involved in the [[immune system]], albeit part of the [[immune system#Innate immune system|innate immune system]]. They play a major role in defending the host from both tumors and virally infected cells. | ||

====Mature B cell neoplasms==== | ====Mature B cell neoplasms==== | ||

| Line 102: | Line 103: | ||

===Working formulation=== | ===Working formulation=== | ||

| − | The '''Working Formulation''', published in 1982, is primarily descriptive. | + | The '''Working Formulation''', published in 1982, is primarily descriptive. It is still occasionally used, but has been superseded by the WHO classification, above. |

====Low grade==== | ====Low grade==== | ||

| Line 120: | Line 121: | ||

*[[Extramedullary plasmacytoma]] | *[[Extramedullary plasmacytoma]] | ||

*Unclassifiable | *Unclassifiable | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

== Genetics == | == Genetics == | ||

| − | Enteropathy associated T-cell lymphoma (EATL) is environmentally induced as a result of the consumption of [[Triticeae glutens]]. In gluten sensitive individuals with EATL 68 | + | Enteropathy associated T-cell lymphoma (EATL) is environmentally induced as a result of the consumption of [[Triticeae glutens]]. In gluten sensitive individuals with EATL, 68 percent are homozygotes of the DQB1*02 subtype at the HLA-DQB1 locus (serotype DQ2) (Al-Toma 2007). |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Lymphoma in animals== | ==Lymphoma in animals== | ||

| − | |||

| − | [[Image:Lymphoma in golden.JPG|thumb|Lymphoma in a | + | ===Lymphoma in dogs=== |

| + | [[Image:Lymphoma in golden.JPG|thumb|Lymphoma in a golden retriever]] | ||

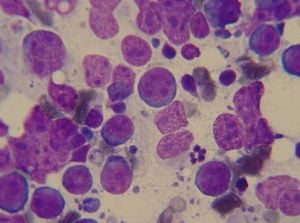

[[Image:Canine lymphoma 1.JPG|thumb|Cytology of lymphoma in a dog]] | [[Image:Canine lymphoma 1.JPG|thumb|Cytology of lymphoma in a dog]] | ||

| − | + | Lymphoma is one of the most common malignant [[tumor]]s to occur in [[dog]]s. The cause is [[genetics|genetic]], but there also suspected environmental factors involved (Morrison 1998), including in one study an increased risk with the use of the [[herbicide]] 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) (Zahm and Blair 1992), although this was not confirmed in another study (Kaneene and Miller 1999) | |

| − | Lymphoma is one of the most common malignant [[tumor]]s to occur in | ||

| − | + | Commonly affected breeds include the [[Boxer (dog)|boxer]], [[Scottish terrier]], [[basset hound]], [[airedale terrier]], [[chow chow]], [[German shepherd dog]], [[poodle]], [[St. Bernard (dog)|St. Bernard]], [[Bulldog|English bulldog]], [[beagle]], and [[rottweiler]] (Morrison 1998). The [[golden retriever]] is especially prone to developing lymphoma, with a lifetime risk of 1:8. (Modiano et al. 2005). | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | General signs and symptoms include depression, fever, weight loss, loss of appetite, and vomiting. [[Hypercalcaemia|Hypercalcemia]] (high blood [[calcium]] levels) occurs in some cases of lymphoma, and can lead to the above signs and symptoms plus increased water drinking, increased urination, and [[cardiac arrhythmia]]s. Multicentric lymphoma presents as painless enlargement of the peripheral lymph nodes. This is seen in areas such as under the jaw, the armpits, the groin, and behind the knees. Enlargement of the liver and spleen causes the abdomen to distend. Mediastinal lymphoma can cause fluid to collect around the lungs, leading to coughing and difficulty breathing. Gastrointestinal lymphoma causes vomiting, [[diarrhea]], and [[melena]] (digested blood in the stool). Lymphoma of the skin is an uncommon occurrence. Signs for lymphoma in other sites depend on the location. | |

| − | |||

| − | === | + | ===Lymphoma in cats=== |

| − | + | Lymphoma is the most common malignancy diagnosed in cats (MVM 2006a). Lymphoma in young cats occurs most frequently following infection with [[feline leukemia virus]] (FeLV) or to a lesser degree [[feline immunodeficiency virus]] (FIV). These cats tend to have involvement of lymph nodes, spine, or mediastinum. Cats with FeLV are 62 times more likely to develop lymphoma, and cats with both FeLV and FIV are 77 times more likely (Ettinger and Feldman 1995). Younger cats tend to have T-cell lymphoma and older cats tend to have B-cell lymphoma (Seo et al. 2006). Cats living with smokers are more than twice as likely to develop lymphoma (O’Rourke 2002). The same forms of lymphoma that are found in dogs also occur in cats, but gastrointestinal is the most common type. Lymphoma of the kidney is the most common [[kidney]] tumor in cats, and lymphoma is also the most common heart tumor (Morrison 1998). | |

| − | + | Cats that develop lymphoma are much more likely to develop more severe symptoms than dogs. Whereas dogs often appear healthy initially except for swollen lymph nodes, cats will often be physically ill. The symptoms correspond closely to the location of the lymphoma. The most common sites for alimentary (gastrointestinal) lymphoma are, in decreasing frequency, the [[small intestine]], the [[stomach]], the junction of the [[ileum]], [[cecum]], and [[colon (anatomy)|colon]], and the colon. Cats with the alimentary form of lymphoma often present with weight loss, rough hair coat, loss of appetite, vomiting and [[diarrhea]], although vomiting and diarrhea are commonly absent as symptoms (Gaschen 2006). | |

| − | + | ===Lymphoma in ferrets=== | |

| + | Lymphoma is common in [[ferret]]s and is the most common cancer in young ferrets. There is some evidence that a [[retrovirus]] may play a role in the development of lymphoma like in cats (Hernandez-divers 2005). The most commonly affected tissues are the [[lymph node]]s, [[spleen]], [[liver]], [[intestine]], [[mediastinum]], [[bone marrow]], lung, and [[kidney]]. | ||

| − | + | In young [[ferret]]s, the disease progresses rapidly. The most common symptom is difficulty breathing caused by enlargement of the [[thymus]] (Mayer 2006). Other symptoms include loss of appetite, weight loss, weakness, depression, and coughing. It can also masquerade as a chronic disease such as an upper respiratory infection or gastrointestinal disease. In older ferrets, lymphoma is usually chronic and can exhibit no symptoms for years (MVM 2006b). Symptoms seen are the same as in young ferrets, plus [[splenomegaly]], abdominal masses, and peripheral lymph node enlargement. | |

| − | + | ==References== | |

| − | + | * Al-Toma, A., W. H. Verbeek, M. Hadithi, B. M. von Blomberg, and C. J. Mulder. 2007. [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=17470479 Survival in refractory coeliac disease and enteropathy associated T cell lymphoma: Retrospective evaluation of single centre experience]. ''Gut''. PMID 17470479. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | * Ettinger, S. J., and E. C. Feldman. 1995. ''Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine'', 4th ed. W. B. Saunders Company. ISBN 0721667953. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | * Gaschen, F. 2006. [http://www.ivis.org/proceedings/wsava/2006/lecture12/GaschenF2.pdf?LA=1 Small intestinal diarrhea: Causes and treatment]. ''Proceedings of the 31st World Congress of the World Small Animal Veterinary Association''. Retrieved January 28, 2007. | |

| − | + | * Hernández-Divers, S. M. 2005. [http://www.vin.com/proceedings/Proceedings.plx?CID=WSAVA2005&PID=10894&O=Generic Ferret diseases]. ''Proceedings of the 30th World Congress of the World Small Animal Veterinary Association''. Retrieved January 28, 2007. | |

| − | + | * Jaffe, E. S. Sarkin. 2001. ''Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues''. Lyon: IARC Press. ISBN 9283224116. | |

| − | + | * Kaneene, J., R. Miller. 1999. Re-analysis of 2,4-D use and the occurrence of canine malignant lymphoma. ''Vet Hum Toxicol'' 41(3): 164-170. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | * Lemole, G. M. 2001. ''The Healing Diet.'' William Morrow. ISBN 0688170730. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | * Longe, J. L. 2005. ''The Gale Encyclopedia of Cancer: A Guide to Cancer and its Treatments''. Detroit: Thomson Gale. ISBN 1414403623. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | * Mayer, J. 2006. [http://www.ivis.org/proceedings/navc/2006/SAE/631.pdf?LA=1 Update on ferret lymphoma]. ''Proceedings of the North American Veterinary Conference''. Retrieved January 28, 2007. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | * Merck Veterinary Manual (MVM). 2006a. [http://www.merckvetmanual.com/mvm/index.jsp?cfile=htm/bc/57000.htm Feline leukemia virus and related diseases: Introduction]. ''The Merck Veterinary Manual''. Retrieved January 28, 2007. | |

| − | + | * Merck Veterinary Manual (MVM). 2006b. http://www.merckvetmanual.com/mvm/index.jsp?cfile=htm/bc/170304.htm Ferret Neoplasia]. ''The Merck Veterinary Manual''. Retrieved January 1, 2007. | |

| − | + | * Modiano, J. M. Breen, R. Burnett, H. Parker, S. Inusah, R. Thomas, P. Avery, K. Lindblad-Toh, E. Ostrander, G. Cutter, and A. Avery. 2005. Distinct B-cell and T-cell lymphoproliferative disease prevalence among dog breeds indicates heritable risk. ''Cancer Res'' 65(13): 5654-5661. PMID 15994938. | |

| − | + | * Morrison, W. B. 1998. ''Cancer in Dogs and Cats'', 1st ed. Williams and Wilkins. ISBN 0683061054. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | + | * O'Rourke, K. 2002. [http://www.avma.org/onlnews/javma/nov02/021101l.asp Lymphoma risk in cats more than doubles if owners are smokers]. ''JAVMA News'' November 1, 2002. Retrieved August 20, 2006. |

| − | |||

| − | + | * Seo, K., U. Choi, B. Bae, M. Park, C. Hwang, D. Kim, and H. Youn. Mediastinal lymphoma in a young Turkish Angora cat. 2006. ''J Vet Sci 7(2): 199-201. PMID 16645348. | |

| − | |||

| + | * Zahm, S., and A. Blair. 1992. Pesticides and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. ''Cancer Res'' 52(19): 5485s-5488s. PMID 1394159 | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | *[http://www.leukemia-lymphoma.org/all_page?item_id=7030 The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society] | + | All links retrieved November 4, 2022. |

| − | *[http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/lymphoma.html MedlinePlus: Lymphoma] | + | *[http://www.leukemia-lymphoma.org/all_page?item_id=7030 The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society]. |

| − | + | *[http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/lymphoma.html MedlinePlus: Lymphoma]. | |

| − | *[http://www.lymphoma.org Lymphoma Research Foundation] | + | *[http://www.lymphoma.org Lymphoma Research Foundation]. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{credit|Lymphoma|142650572|Lymphoma_in_animals|141714943}} | {{credit|Lymphoma|142650572|Lymphoma_in_animals|141714943}} | ||

| − | [[Category: | + | [[Category:Life sciences]] |

| + | [[Category:Health and disease]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Diseases]] | ||

Latest revision as of 03:16, 5 November 2022

| Lymphoma Classification and external resources | |

| ICD-10 | C81-C96 |

|---|---|

| ICD-O: | 9590-9999 |

| MeSH | D008223 |

Lymphoma is any of a diverse group of cancers that originate in lymphocytes of the lymphatic system, a secondary (but open) circulatory system in vertebrates.

In lymphoma, the cells in the lymphatic system grow abnormally, dividing too rapidly and growing without any order or control (Longe 2005). As a result, too much tissue develops and tumors are formed. Since lymph is widely distributed in the body, with twice as much lymph as blood and twice as many lymph vessels as blood vessels, the cancer may occur in many areas, such as the liver, spleen, and bone marrow.

The lymphatic system plays a crucial role in maintaining homeostasis as well as good health. Lemole (2001) claims that the key to health is a healthy lymphatic system, specifically stating "you can eliminate 70 percent of the chronic illnesses that are in part the result of that system being clogged." Among measures recommended for a healthy lymphatic system are exercise, reduction of stress, massages, and a healthy diet.

Lymphoma represents a breakdown in the intricate coordination of the lymphatic system. Ironically, the lymphatic system is fundamentally important for combating cancer cells—as well as foreign bodies, such as viruses and bacteria, and combating heart disease and arthritis as well. It is those cancers that originate in the lymphatic system that are referred to as lymphomas. But cancers can also originate outside the lymphatic system and then make their way into lymphoid tissues and glands.

There are many types of lymphoma. Lymphomas are part of the broad group of diseases called hematological neoplasms.

Lymphoma commonly is categorized broadly as Hodgkin's lymphoma (HL) and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL, all other types of lymphoma). These are distinguished by cell type (Longe 2005). Scientific classification of the types of lymphoma is more detailed. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the affliction was called simply Hodgkin's Disease, as it was discovered by Thomas Hodgkin in 1832.

Prevalence

According to the U.S. National Institutes of Health, lymphomas account for about five percent of all cases of cancer in the United States. Hodgkin's lymphoma accounts for less than one percent of all cases of cancer in the United States.

Because the lymphatic system is part of the body's immune system, patients with weakened immune system, such as from HIV infection or from certain drugs or medication, also have a higher incidence of lymphoma.

Classification

WHO classification

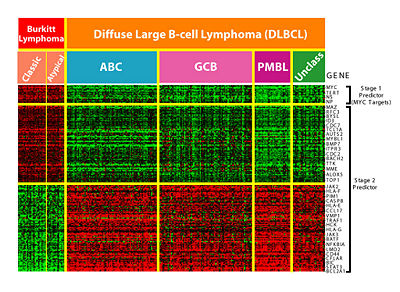

The WHO Classification, published by the World Health Organization in 2001, is the latest classification of lymphoma (Sarkin 2001). It was based upon the "Revised European-American Lymphoma classification" (REAL).

This classification attempts to classify lymphomas by cell type (i.e. the normal cell type that most closely resembles the tumor). They are classified in three large groups: B cell tumors; T cell and natural killer cell tumors; Hodgkin lymphoma, as well as other minor groups.

B cells are lymphocytes (a class of white blood cells) that play a large role in the adaptive immune system by making antibodies to identify and neutralize invading pathogens like bacteria and viruses. Specially, B cells play the major role in the humoral immune response, as opposed to the cell-mediated immune response that is governed by T cells, another type of lymphocyte. T cells can be distinguished from B cells and natural killer (NK) cells by the presence of a special receptor on their cell surface that is called the T cell receptor (TCR). Lymphocyte-like natural killer (NK) cells also are involved in the immune system, albeit part of the innate immune system. They play a major role in defending the host from both tumors and virally infected cells.

Mature B cell neoplasms

- Chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma

- B-cell prolymphocytic leukemia

- Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma/Waldenström macroglobulinemia

- Splenic marginal zone lymphoma

- Plasma cell neoplasms

- Plasma cell myeloma

- Plasmacytoma

- Monoclonal immunoglobulin deposition diseases

- Heavy chain diseases

- Extranodal marginal zone B cell lymphoma (MALT lymphoma)

- Nodal marginal zone B cell lymphoma

- Follicular lymphoma

- Mantle cell lymphoma

- Diffuse large B cell lymphoma

- Mediastinal (thymic) large B cell lymphoma

- Intravascular large B cell lymphoma

- Primary effusion lymphoma

- Burkitt lymphoma/leukemia

- Lymphomatoid granulomatosis

Mature T cell and natural killer (NK) cell neoplasms

- T cell prolymphocytic leukemia

- T cell large granular lymphocytic leukemia

- Aggressive NK cell leukemia

- Adult T cell leukemia/lymphoma

- Extranodal NK/T cell lymphoma, nasal type

- Enteropathy-type T cell lymphoma

- Hepatosplenic T cell lymphoma

- Blastic NK cell lymphoma

- Mycosis fungoides / Sezary syndrome

- Primary cutaneous CD30-positive T cell lymphoproliferative disorders

- Primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma

- Lymphomatoid papulosis

- Angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphoma

- Peripheral T cell lymphoma, unspecified

- Anaplastic large cell lymphoma

Hodgkin Lymphoma

- Nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma

- Classical Hodgkin lymphoma

- Nodular sclerosis

- Mixed cellularity

- Lymphocyte-rich

- Lymphocyte depleted or not depleted

Immunodeficiency-associated lymphoproliferative disorders

- Associated with a primary immune disorder

- Associated with the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)

- Post-transplant

- Associated with Methotrexate therapy

Histiocytic and dendritic cell neoplasms

- Histiocytic sarcoma

- Langerhans cell histiocytosis

- Langerhans cell sarcoma

- Interdigitating dendritic cell sarcoma/tumor

- Follicular dendritic cell sarcoma/tumor

- Dendritic cell sarcoma, unspecified

Working formulation

The Working Formulation, published in 1982, is primarily descriptive. It is still occasionally used, but has been superseded by the WHO classification, above.

Low grade

- Malignant Lymphoma, small lymphocytic (chronic lymphocytic leukemia)

- Malignant Lymphoma, follicular, predominantly small cleaved cell

- Malignant Lymphoma, follicular, mixed (small cleaved and large cell)

High grade

- Malignant Lymphoma, large cell, immunoblastic

- Malignant Lymphoma, lymphoblastic

- Malignant Lymphoma, small non-cleaved cells (Burkitt's lymphoma)

Miscellaneous

- Composite

- Mycosis fungoides

- Histiocytic

- Extramedullary plasmacytoma

- Unclassifiable

Genetics

Enteropathy associated T-cell lymphoma (EATL) is environmentally induced as a result of the consumption of Triticeae glutens. In gluten sensitive individuals with EATL, 68 percent are homozygotes of the DQB1*02 subtype at the HLA-DQB1 locus (serotype DQ2) (Al-Toma 2007).

Lymphoma in animals

Lymphoma in dogs

Lymphoma is one of the most common malignant tumors to occur in dogs. The cause is genetic, but there also suspected environmental factors involved (Morrison 1998), including in one study an increased risk with the use of the herbicide 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) (Zahm and Blair 1992), although this was not confirmed in another study (Kaneene and Miller 1999)

Commonly affected breeds include the boxer, Scottish terrier, basset hound, airedale terrier, chow chow, German shepherd dog, poodle, St. Bernard, English bulldog, beagle, and rottweiler (Morrison 1998). The golden retriever is especially prone to developing lymphoma, with a lifetime risk of 1:8. (Modiano et al. 2005).

General signs and symptoms include depression, fever, weight loss, loss of appetite, and vomiting. Hypercalcemia (high blood calcium levels) occurs in some cases of lymphoma, and can lead to the above signs and symptoms plus increased water drinking, increased urination, and cardiac arrhythmias. Multicentric lymphoma presents as painless enlargement of the peripheral lymph nodes. This is seen in areas such as under the jaw, the armpits, the groin, and behind the knees. Enlargement of the liver and spleen causes the abdomen to distend. Mediastinal lymphoma can cause fluid to collect around the lungs, leading to coughing and difficulty breathing. Gastrointestinal lymphoma causes vomiting, diarrhea, and melena (digested blood in the stool). Lymphoma of the skin is an uncommon occurrence. Signs for lymphoma in other sites depend on the location.

Lymphoma in cats

Lymphoma is the most common malignancy diagnosed in cats (MVM 2006a). Lymphoma in young cats occurs most frequently following infection with feline leukemia virus (FeLV) or to a lesser degree feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV). These cats tend to have involvement of lymph nodes, spine, or mediastinum. Cats with FeLV are 62 times more likely to develop lymphoma, and cats with both FeLV and FIV are 77 times more likely (Ettinger and Feldman 1995). Younger cats tend to have T-cell lymphoma and older cats tend to have B-cell lymphoma (Seo et al. 2006). Cats living with smokers are more than twice as likely to develop lymphoma (O’Rourke 2002). The same forms of lymphoma that are found in dogs also occur in cats, but gastrointestinal is the most common type. Lymphoma of the kidney is the most common kidney tumor in cats, and lymphoma is also the most common heart tumor (Morrison 1998).

Cats that develop lymphoma are much more likely to develop more severe symptoms than dogs. Whereas dogs often appear healthy initially except for swollen lymph nodes, cats will often be physically ill. The symptoms correspond closely to the location of the lymphoma. The most common sites for alimentary (gastrointestinal) lymphoma are, in decreasing frequency, the small intestine, the stomach, the junction of the ileum, cecum, and colon, and the colon. Cats with the alimentary form of lymphoma often present with weight loss, rough hair coat, loss of appetite, vomiting and diarrhea, although vomiting and diarrhea are commonly absent as symptoms (Gaschen 2006).

Lymphoma in ferrets

Lymphoma is common in ferrets and is the most common cancer in young ferrets. There is some evidence that a retrovirus may play a role in the development of lymphoma like in cats (Hernandez-divers 2005). The most commonly affected tissues are the lymph nodes, spleen, liver, intestine, mediastinum, bone marrow, lung, and kidney.

In young ferrets, the disease progresses rapidly. The most common symptom is difficulty breathing caused by enlargement of the thymus (Mayer 2006). Other symptoms include loss of appetite, weight loss, weakness, depression, and coughing. It can also masquerade as a chronic disease such as an upper respiratory infection or gastrointestinal disease. In older ferrets, lymphoma is usually chronic and can exhibit no symptoms for years (MVM 2006b). Symptoms seen are the same as in young ferrets, plus splenomegaly, abdominal masses, and peripheral lymph node enlargement.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Al-Toma, A., W. H. Verbeek, M. Hadithi, B. M. von Blomberg, and C. J. Mulder. 2007. Survival in refractory coeliac disease and enteropathy associated T cell lymphoma: Retrospective evaluation of single centre experience. Gut. PMID 17470479.

- Ettinger, S. J., and E. C. Feldman. 1995. Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 4th ed. W. B. Saunders Company. ISBN 0721667953.

- Gaschen, F. 2006. Small intestinal diarrhea: Causes and treatment. Proceedings of the 31st World Congress of the World Small Animal Veterinary Association. Retrieved January 28, 2007.

- Hernández-Divers, S. M. 2005. Ferret diseases. Proceedings of the 30th World Congress of the World Small Animal Veterinary Association. Retrieved January 28, 2007.

- Jaffe, E. S. Sarkin. 2001. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon: IARC Press. ISBN 9283224116.

- Kaneene, J., R. Miller. 1999. Re-analysis of 2,4-D use and the occurrence of canine malignant lymphoma. Vet Hum Toxicol 41(3): 164-170.

- Lemole, G. M. 2001. The Healing Diet. William Morrow. ISBN 0688170730.

- Longe, J. L. 2005. The Gale Encyclopedia of Cancer: A Guide to Cancer and its Treatments. Detroit: Thomson Gale. ISBN 1414403623.

- Mayer, J. 2006. Update on ferret lymphoma. Proceedings of the North American Veterinary Conference. Retrieved January 28, 2007.

- Merck Veterinary Manual (MVM). 2006a. Feline leukemia virus and related diseases: Introduction. The Merck Veterinary Manual. Retrieved January 28, 2007.

- Merck Veterinary Manual (MVM). 2006b. http://www.merckvetmanual.com/mvm/index.jsp?cfile=htm/bc/170304.htm Ferret Neoplasia]. The Merck Veterinary Manual. Retrieved January 1, 2007.

- Modiano, J. M. Breen, R. Burnett, H. Parker, S. Inusah, R. Thomas, P. Avery, K. Lindblad-Toh, E. Ostrander, G. Cutter, and A. Avery. 2005. Distinct B-cell and T-cell lymphoproliferative disease prevalence among dog breeds indicates heritable risk. Cancer Res 65(13): 5654-5661. PMID 15994938.

- Morrison, W. B. 1998. Cancer in Dogs and Cats, 1st ed. Williams and Wilkins. ISBN 0683061054.

- O'Rourke, K. 2002. Lymphoma risk in cats more than doubles if owners are smokers. JAVMA News November 1, 2002. Retrieved August 20, 2006.

- Seo, K., U. Choi, B. Bae, M. Park, C. Hwang, D. Kim, and H. Youn. Mediastinal lymphoma in a young Turkish Angora cat. 2006. J Vet Sci 7(2): 199-201. PMID 16645348.

- Zahm, S., and A. Blair. 1992. Pesticides and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Cancer Res 52(19): 5485s-5488s. PMID 1394159

External links

All links retrieved November 4, 2022.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.