Difference between revisions of "Lunda Empire" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

==Governance== | ==Governance== | ||

| − | The Mwaat Yaav was advised by a council of royal dignitaries. Local chiefs exercised a considerable autonomy, provided they paid tribute to the Mwaat Yaav. Power may originally have been passed on down through male line. However, possibly due to contact with an increasingly large number of matrilineal systems, succession became matrilineal.<ref name=Iowa>[http://www.uiowa.edu/~africart/toc/people/Lunda.html Lunda Information.] The University of Iowa. Retrieved October 18, 2008.</ref> | + | The Mwaat Yaav was advised by a council of royal dignitaries. Local chiefs exercised a considerable autonomy, provided they paid tribute to the Mwaat Yaav. Conquered chiefs were kept in place, and given the title Mwaant (owner of land.)<ref>Mukenge, page 17.</ref> Power may originally have been passed on down through male line. However, possibly due to contact with an increasingly large number of matrilineal systems, succession became matrilineal.<ref name=Iowa>[http://www.uiowa.edu/~africart/toc/people/Lunda.html Lunda Information.] The University of Iowa. Retrieved October 18, 2008.</ref> |

The Empire "probably governed a million or more subjects."<ref>Clark, page 375.</ref> | The Empire "probably governed a million or more subjects."<ref>Clark, page 375.</ref> | ||

| − | Aoppiah and Gates describe their administrative system as "cohesive" and "complex."<ref>Appiah and Gaets, page 1209.</ref> A small [[police]] "corps enforced the king's orders around the capital" and traveling chiefs, or ''kawatta'' acted as the kings envoys to the local chiefs, collecting tribute. The most distant chiefs were visited annually.<ref>Mukenge, page 17.</ref> | + | Aoppiah and Gates describe their administrative system as "cohesive" and "complex."<ref>Appiah and Gaets, page 1209.</ref> A small [[police]] "corps enforced the king's orders around the capital" and traveling chiefs, or ''kawatta'' acted as the kings envoys to the local chiefs, collecting tribute. The most distant chiefs were visited annually.<ref>Mukenge, page 17.</ref> Minimal interference by the central government in the affairs of the provinces helped to keep the [[peace]] in a system where "central control" would have been "seen as exploitation."<ref><ref>Mukenge, page 18.</ref> |

==Religion== | ==Religion== | ||

Revision as of 01:30, 19 October 2008

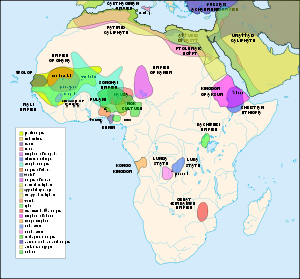

The Kingdom of Lunda (c. 1665-1887), also known as the Lunda Empire was a pre-colonial African confederation of states in what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo, north-eastern Angola and northwestern Zambia. Its central state was in Katanga. The Paramount Ruler, the Mwaant Yaav, is still recognized as the chief of a "traditional state."[1] The Lunda are a Bantu-speaking people.

During the slave trade, the Lundu Empire provided a large number of captives to the Portuguese.

Origin

According to Thomas, the Lunda were originally nomads who kept moving, adopting children rather than procreating. He describes the Lunda of this nomadic phase as "palm-wine-drinkign and often cannibalistic .Later, they settled down and adopted a "conventional attitude to procreation and families."[2] Initially the core of what would become the Lunda Empire a simple village called a "gaand" in the KiLunda language. It was ruled over by a king called the Mwaanta Gaand or Mwaantaangaand. One of these rulers, Ilunga Tshibinda came from the kingdom of Luba where his brother ruled and married a princess from an area to the south.[3] Their son became the first paramount ruler of the Lunda creating the title of Mwanta Yaav, which bears his name.

Expansion

According to Appiah and Gates, the Lundu were too small in number to survive by farming, so raided neighboring villages to put captives to work in their fields. They later "colonized remote villages and forced them to pay crop tributes to the Lundu king."[4] Their role in the slave trade later led to their expansion throughout the Luapula Valley.

Governance

The Mwaat Yaav was advised by a council of royal dignitaries. Local chiefs exercised a considerable autonomy, provided they paid tribute to the Mwaat Yaav. Conquered chiefs were kept in place, and given the title Mwaant (owner of land.)[5] Power may originally have been passed on down through male line. However, possibly due to contact with an increasingly large number of matrilineal systems, succession became matrilineal.[6]

The Empire "probably governed a million or more subjects."[7]

Aoppiah and Gates describe their administrative system as "cohesive" and "complex."[8] A small police "corps enforced the king's orders around the capital" and traveling chiefs, or kawatta acted as the kings envoys to the local chiefs, collecting tribute. The most distant chiefs were visited annually.[9] Minimal interference by the central government in the affairs of the provinces helped to keep the peace in a system where "central control" would have been "seen as exploitation."Cite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag

Religion

The chiefs may have combined a political and a spiritual role. The creator God was Nzambi (associated with the sky), the Bantu supreme deity, although supplication to him was made by invoking the help of ancestral spirits. Divination was practices to determine which ancestors needed to be appeased. Nzambi is said to have a particular concern for the welfare of the poor.[6][10]

Economy

The Empires economy was mixed, including agriculture and trade as well as hunting and fishing. Women undertook agricultural work, farming such crops as maize, yams, sorghum, squash, beans, sweet potatoes, palm oil trees, and tobacco. Trading commodities included slaves and ivory, copper and salt. Trading partners included Arabs and from the fifteenth century the Portuguese. They received weapons and textiles in return.

According to Clark, the empire thrived on the slave trade but "it is unlikely that the external trade ever rose to 3,000 slaves per annum, most of whom were foreign captives."[11] However, according to Appiah Gates and , the Lundu Empire was one of the largest suppliers of slaves; "In 1850, a slave trade estimated that one third of all slaves traded in the previous century had been sold by the Lunda Kingdom." They "protested the end of the Portuguese slave trade on the basis that they would have to resort to killing the criminals if they could no longer sell them."[12]

Apex

The Lunda Kingdom controlled some 150,000 square kilometers by 1680. The state doubled in size to around 300,000 square kilometers at its height in the 19th century.[13] The Mwata Yamvos of Lunda became powerful militarily from their base of 175,000 inhabitants. Through marriage with descendants of the Luba kings, they gained political ties. The Lunda people were able to settle and colonlize other areas and tribes, thus extending their empire through southwest Katanga into Angola and north-western Zambia, and eastwards across Katanga into what is now the Luapula Province of Zambia.

The strength and prosperity of the kingdom enabled its military and ruling classes to conquer other tribes, especially to the East. In the 18th Century a number of migrations took place as far as the region to the south of Lake Tanganyika. The Bemba people of Northern Zambia descended from Luba migrants who arrived in Zambia throughout the 17th century. At the same time, a Lunda chief and warrior called Mwata Kazembe set up an Eastern Lunda kingdom in the valley of the Luapula River.

Collapse

The kingdom of Lunda came to an end in the 19th century when it was invaded by the Chokwe who were armed with guns. The Chokwe then established their own kingdom with their language and customs. Lunda chiefs and people continued to live in the Lunda heartland but were diminished in power.

At the start of the colonial era (1884) the Lunda heartland was divided between Portuguese Angola, King Leopold II of Belgium's Congo Free State and the British in North-Western Rhodesia, which became Angola, Democratic Republic of Congo and Zambia respectively. Lunda leaders, however, continues to resist Belgium rule until they were finally defeated in 1909. The Belgiums however left much of the structures of the Lundu Empire in place, choosing to use "preexisting state structures to facilitate colonial rule" thus the Lundu "remained fairly cohesive throughout the colonial period."[14]

Rulers

Mwaantaangaand of Lunda Kingdom

- Nkonda Matit (ruled late 16th century)

- Cibind Yirung (ruled c. 1600-c. 1630)

- Yaav I a Yirung (ruled c. 1630-c. 1660)

- Yaav II a Nawej (ruled c. 1660-c. 1690)

Mwaant Yaav of Lunda Empire

- Mbala I Yaav (ruled c. 1690-c. 1720)

- Mukaz Munying Kabalond (ruled c. 1720)

- Muteba I Kat Kateng (ruled c. 1720-c. 1750)

- Mukaz Waranankong (ruled c. 1750-c. 1767)

- Nawej Mufa Muchimbunj (ruled c. 1767-c. 1775)

- Cikombe Yaava (ruled c. 1775-c. 1800)

- Nawej II Ditend (ruled c. 1800-1852)

- Mulaj a Namwan (ruled 1852-1857)

- Cakasekene Naweej (ruled 1857)

- Muteba II a Cikombe (ruled 1857-1873)

- Mbala II a Kamong Isot (ruled 1873-1874)

- Mbumb I Muteba Kat (ruled 1874-1883)

- Cimbindu a Kasang (ruled 1883-1884)

- Kangapu Nawej (ruled 1884-1885)

- Mudib (ruled 1885-1886)

- Mutand Mukaz (ruled 1886-1887)

- Mbala III a Kalong (ruled 1887)

Mwaant Yaav under the Congo Free State

- Mushidi I a Nambing (ruled 1887-1907)

- Muteba III a Kasang (ruled 1907-1908)

Mwaant Yaav under the Belgian Congo

- Muteba III a Kasang cont. (ruled 1908-1920)

- Kaumba (ruled 1920-1951)

- Yaav a Nawej III (ruled 1951-1960)

Mwaant Yaav under Katanga

- Yaav a Nawej III cont. (ruled 1960-1962)

Mwaant Yaav under Republic of Congo

- Yaav a Nawej III cont. (ruled 1962-1963)

- Mushidi II Kawel a Kamin (ruled 1963-1964)

- Mushidi II Kawel a Kamin (ruled 1964-1965 )

- Muteb II Mushidi cont. (ruled 1965-1971)

Mwaant Yaav under Zaire

- Muteb II Mushidi cont. (ruled 1971-1973)

- Mbumb II Muteb (ruled 1973-1997)

Mwaant Yaav under Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Mbumb II Muteb cont. (ruled 1997- current)

Legacy

The time of slavery is over. In our increasingly globalized society there is no need, or excuse, for treating any people as slaves, as property, as inferior. The laws have recognized this point; it is up to all people to follow. Unfortunately, trafficking in human beings remains common in many parts of the world, with the innocent sold into prostitution and other degrading and dangerous situation. Human society has not yet achieved a true conscience, guiding all people to behave with love and respect towards others. Such an internal change in human nature is required to end the abuse of others that is slavery.

Notes

- ↑ Cahoon, Ben. 2000. Congo (Kinshasa) Traditional states. World Statesmen. Retrieved October 18, 2008.

- ↑ Thomas, page 167.

- ↑ Gates and Appiah, page 1209.

- ↑ Appiah and Gates, page 1209.

- ↑ Mukenge, page 17.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Lunda Information. The University of Iowa. Retrieved October 18, 2008.

- ↑ Clark, page 375.

- ↑ Appiah and Gaets, page 1209.

- ↑ Mukenge, page 17.

- ↑ Nzambi. Answers.com. Retrieved October 18, 2008.

- ↑ Clark, page 375.

- ↑ Appiah and Gates, page 1209.

- ↑ Thornton, page 104

- ↑ Appiah and Gates, page 1208.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

Appiah, Anthony, and Henry Louis Gates. 1999. Africana: the encyclopedia of the African and African American experience. New York: Basic Civitas Books. ISBN 9780465000715

- Bustin, Edouard. 1975. Lunda under Belgian rule: the politics of ethnicity. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674539532

- Clark, J. Desmond, J. D. Fage, Roland Oliver, Richard Gray, John E. Flint, G. N. Sanderson, A. D. Roberts, and Michael Crowder. 1975. The Cambridge history of Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521204132

- Mukenge, Tshilemalema. 2002. Culture and customs of the Congo. Culture and customs of Africa. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press. ISBN 9780313314858

- Thomas, Hugh. 1997. The slave trade: the story of the Atlantic slave trade, 1440-1870. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9780684810638

- Thornton, John K. 1992. Africa and Africans in the making of the Atlantic world, 1400-1680. Studies in comparative world history. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521392334

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.