Lughnasadh

| Lughnasadh | |

|---|---|

| Observed by | Gaels, Irish People, Scottish People, Neopagans |

| Type | Christianized folk traditions, Pre-Christian, Pagan |

| Date | Northern Hemisphere: 1 August Southern Hemisphere: February 1 |

| Celebrations | Traditional celebration of first fruits / first harvest |

| Related to | Lammas |

Lughnasadh (Old Irish, pronounced IPA: [luɣnəsəð]; Modern Irish Lá Lúnasa; Modern Gaelic Lùnastal) is a Gaelic holiday traditionally associated with the first of August.

Ancient celebration

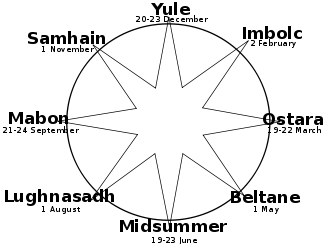

Lughnasadh was one of the four main festivals of the medieval Irish calendar: Imbolc at the beginning of February, Beltane on the first of May, Lughnasadh in August, and Samhain in October. One early Continental Celtic calendar was based on the lunar, solar, and vegetative cycles, so the actual calendar date in ancient times may have varied.[citation needed] Lughnasadh marked the beginning of the harvest season, the ripening of first fruits, and was traditionally a time of community gatherings, market festivals, horse races and reunions with distant family and friends. Among the Irish it was a favored time for handfastings - trial marriages that would generally last a year and a day, with the option of ending the contract before the new year, or later formalizing it as a more permanent marriage.[1][2][3]

In Celtic mythology, the Lughnasadh festival is said to have been begun by the god Lugh, as a funeral feast and games commemorating his foster-mother, Tailtiu, who died of exhaustion after clearing the plains of Ireland for agriculture. The first location of the Áenach Tailteann was at the site of modern Teltown, located between Navan and Kells. Historically, the Áenach Tailteann gathering was a time for contests of strength and skill, and a favored time for contracting marriages and winter lodgings. A peace was declared at the festival, and religious celebrations were also held. A similar Lughnasadh festival was held at Carmun (whose exact location is under dispute). Carmun is also believed to have been a goddess of the Celts, perhaps one with a similar story as Tailtiu.[3][4]

A festival corresponding to Lughnasadh may have been observed by the Gauls at least up to the first century; on the Coligny calendar, the eighth day of the first half of the month Edrinios, is marked with the inscription TIOCOBREXTIO that identifies other major feasts. The same date was later adopted for the meeting of all the representatives of Gaul at the Condate Altar in Gallo-Roman times. During the reign of Augustus Caesar the Romans instituted a celebration on August 1 to the genius of the emperor in Lyon , capital of Roman Gaul, named after the Celtic god Lugh. Lyon (modern French) derives from the Latinized Gaulish word "Lugdunum" ("Lugodunon" in Gaulish), literally Lugh's (Lug) fortress (dunos-dunon).

Modern day celebration

On mainland Europe and in Ireland many people continue to celebrate the holiday with bonfires and dancing. The Christian church has established the ritual of blessing the fields on this day. In the Irish diaspora, survivals of the Lá Lúnasa festivities are often seen by some families still choosing August as the traditional time for family reunions and parties, though due to modern work schedules these events have sometimes been moved to adjacent secular holidays, such as the Fourth of July in the United States.[1][3]

On August 1st, the national holiday of Switzerland, it is traditional to celebrate with bonfires. This practice may trace back to the Lughnasadh celebrations of the Helvetii, Celtic people of the Iron Age who lived in what is now Switzerland.

In Northern Italy, e.g. in Canzo, Lughnasadh traditions are still incorporated into modern 1 August festivities.

Etymology

In Old Irish, the name of the festival has at various points in time been written Lughnasa, Lughnasad or Lughnassadh.

In Modern Irish (Gaeilge), the name for the month of August is Lúnasa, with the festival itself being called Lá Lúnasa ("the day of Lúnasa").

In Modern Gaelic (Gàidhlig), the festival and the month are both called Lùnastal.

In Welsh (Cymraeg), the day is know as Calan Awst, an originally Latin term.

In Gaulish, the festival may have been called something like *Lugunassatis (the asterisk indicates this is a reconstructed form).

Revival

Neopaganism

Lughnasadh is observed by Neopagans in various forms, and by a variety of names. As forms of Neopaganism can be quite different and have very different origins, these representations can vary considerably despite the shared name. Some celebrate in a manner as close as possible to how the Ancient Celts and Living Celtic cultures have maintained the traditions, while others observe the holiday with rituals culled from numerous other unrelated sources, Celtic culture being only one of the sources used.[5][6][7]

Celtic Reconstructionism

Like other Reconstructionist traditions, Celtic Reconstructionists place emphasis on historical accuracy, and base their celebrations and rituals on traditional lore from the living Celtic cultures, as well as research into the older beliefs of the polytheistic Celts. Celtic Reconstructionist Pagans tend to celebrate Lughnasadh at the time of first fruits, or on the full moon that falls closest to this time. In the Northeastern United States, this is often the time of the blueberry harvest, while in the Pacific Northwest the blackberries are often the festival fruit.[1][8]

In Celtic Reconstructionism (CR), Lá Lúnasa is seen as a time to give thanks to the spirits and deities for the beginning of the harvest season, and to propitiate them with offerings and prayers to not harm the still-ripening crops. The god Lugh is honored by many at this time, as he is a deity of storms and lightning, especially the storms of late summer. However, gentle rain on the day of the festival is seen as his presence and his bestowing of blessings. Many CRs also honor the goddess Tailitu on this day, and may seek to keep the Cailleachan ("Storm Hags") from damaging the crops, much in the way appeals are made to Lugh.[1][8][9][10]

Wicca

In Wicca, Lughnasadh is one of the eight "sabbats" or solar festivals in the Wiccan Wheel of the Year. It is the first of the three autumn harvest festivals, the other two being the Autumn equinox (or Mabon) and Samhain. One telling of the story commemorates the sacrifice and death of the Wiccan Corn God; in its cycle of death, nurturing the people, and rebirth, the corn is considered an aspect of their Sun God. Some Wiccans mark the holiday by baking a figure of the god in bread, and then symbolically sacrificing and eating it. These celebrations are not based on Celtic culture, despite the use of a Celtic name used for the sabbat.[11][7] The Celtic name seems to have been a late adoption among Wiccans, since in early versions of Wiccan literature the festival is merely referred to as "August Eve".[12]

Lammas

In some English-speaking countries in the Northern Hemisphere, August 1 is Lammas Day (loaf-mass day), the festival of the first wheat harvest of the year. On this day it was customary to bring to church a loaf made from the new crop. In many parts of England, tenants were bound to present freshly harvested wheat to their landlords on or before the first day of August. In the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, where it is referred to regularly, it is called "the feast of first fruits." The blessing of new fruits was performed annually in both the Eastern and Western Churches on the first, or the sixth, of August. The Sacramentary of Pope Gregory I (died 604) specifies the sixth.[citation needed]

In mediæval times the feast was known as the "Gule of August," but the meaning of "gule" is unknown. Ronald Hutton suggests that it may be an Anglicisation of Gŵyl Awst, the Welsh name for August 1 meaning "feast of August," but this is not certain. If so, this points to a pre-Christian origin for Lammas among the Anglo-Saxons and a link to the Gaelic festival of Lughnasadh. 'Gule' could also come from 'Geohhol' (Old English form of 'jule') and thus Lammas Day was the 'Jule of August'.[citation needed]

There are several historical references to it being known as Lambess eve, such as 'Publications of the Scottish Historical Society' 1964 and this alternate name is the origin of the Lambess surname, just as Hallowmass and Christmas were also adopted as familial titles.

People in the Southern Hemisphere that celebrate Lammas do so February 1, to reflect the 6 month offset of seasons on the other side of the planet.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Danaher, Kevin (1972) The Year in Ireland: Irish Calendar Customs Dublin, Mercier. ISBN 1-85635-093-2 pp.167-186

- ↑ Chadwick, Nora (1970) The Celts London, Penguin. ISBN 0-14-021211-6 p. 181

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 McNeill, F. Marian (1959) The Silver Bough, Vol. 2. William MacLellan, Glasgow ISBN 0-85335-162-7 pp.94-101

- ↑ MacKillop, James (1998) A Dictionary of Celtic Mythology. Oxford, Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280120-1 pp.309-10, 395-6, 76, 20

- ↑ Adler, Margot (1979, revised edition 2006) Drawing Down the Moon: Witches, Druids, Goddess-Worshippers, and Other Pagans in America Today. Boston, Beacon Press ISBN 0-8070-3237-9. pp.3, 243-299

- ↑ McColman, Carl (2003) Complete Idiot's Guide to Celtic Wisdom. Alpha Press ISBN 0-02-864417-4. p.51

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Hutton, Ronald. The Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles. Oxford, Blackwell, 331–341. ISBN 0-631-18946-7.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 McColman (2003) pp.12, 51

- ↑ Bonewits, Isaac (2006) Bonewits's Essential Guide to Druidism. New York, Kensington Publishing Group ISBN 0-8065-2710-2. pp.186-7, 128-140

- ↑ McNeill, F. Marian (1957) The Silver Bough, Vol. 1. William MacLellan, Glasgow ISBN 0-85335-161-9 p.119

- ↑ Starhawk (1979, 1989) The Spiral Dance: A Rebirth of the Ancient Religion of the Great Goddess. New York, Harper and Row ISBN 0-06-250814-8 pp.191-2 (revised edition)

- ↑ The Gardnerian Book of Shadows online

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Carmichael, Alexander. Carmina Gadelica. Lindisfarne Press, 1992. ISBN 0940262509

- Danaher, Kevin. The Year in Ireland. Dublin: Mercier, 1972. ISBN 1856350932

- MacKillop, James. Dictionary of Celtic Mythology. Oxford University Press, 1998. ISBN 0192801201

- McNeill, F. Marian. Silver Bough: Calendar of Scottish National Festivals, Vols. 1-4. Glasgow: Stuart Titles Ltd, 1990. ISBN 0948474041

- MacNeill, Máire, ''The Festival of Lughnasa (Oxford University Press) 1962. Republished 2008. ISBN 0-906426-10-3.

- Melia, Daniel F., "The Grande Troménie at Locronan: A Major Breton Lughnasa Celebration" The Journal of American Folklore 91 No. 359 (January 1978), pp. 528-542.

- Hutton, Ronald. The Stations of the Sun. Oxford, 2001. ISBN 0192854488

- 'Publications of the Scottish Historical Society' 1964

- Cabot, Laurie, and Jean Mills. Celebrate the Earth: A Year of Holidays in the Pagan Tradition. New York, NY: Dell Publisching, 1994. ISBN 0385309201

- Hamilton, Claire. Celtic Book of Seasonal Meditations: Celebrate the Traditions of the Ancient Celts. York Beach, ME: Red Wheel/Weiser, 2003. ISBN 1590030559

- Hutton, Ronald. The Pagan Religions of the Ancient British Isles: Their Nature and Legacy. Wiley-Blackwell, 1993. ISBN 0631189467

External links

- Celtic Religious Holidays

- The Celtic Year: Lughnasadh

- Lughnasadh

- Lammas, Lughnasadh

- Lughnasadh (Lammas)

| |||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.