Difference between revisions of "Labyrinthodontia" - New World Encyclopedia

Rick Swarts (talk | contribs) |

Rick Swarts (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

The name Labryinthodonita , which is from the [[Greek language|Greek]] for "maze-toothed," describes the pattern of infolding of the [[dentine]] and [[Tooth enamel|enamel]] of the teeth, which are often the only part of the creatures that [[fossilize]]. They are also distinguished by a heavy solid skull, and complex vertebrae, the structure of which is useful in older classifications of the group. | The name Labryinthodonita , which is from the [[Greek language|Greek]] for "maze-toothed," describes the pattern of infolding of the [[dentine]] and [[Tooth enamel|enamel]] of the teeth, which are often the only part of the creatures that [[fossilize]]. They are also distinguished by a heavy solid skull, and complex vertebrae, the structure of which is useful in older classifications of the group. | ||

| − | Although a traditional and still common designation, this group has fallen out of favor | + | Although a traditional and still common designation, this group has fallen out of favor in recent [[taxonomy|taxonomies]] because it is paraphyletic—that is, the group does not include all the descendants of the most recent common ancestor. |

{{Paleozoic Footer}} | {{Paleozoic Footer}} | ||

{{Mesozoic Footer}} | {{Mesozoic Footer}} | ||

| − | + | ==Description== | |

| − | + | The amphibians that lived in the Paleozoic traditionally were divided into the two subclasses of Labyrinthodontia and Lepospondyli based on the character of their vertebrae (Panchen 1967). Labyrinthodonts are named for the pattern of [[infolding]] of the [[dentine]] and [[Tooth enamel|enamel]] of the teeth, that resembles a [[maze]] (or [[labyrinth]]). They are believed to have representatives that were aquatic, semiaquatic, and terrestrial, and that the passage from aquatic environments to terrestrial took place beginning in the Late Devonian (NSMC 2002). They are considered to be descendant from crossopterygian fishes, and gave rise to the modern amphibians and the reptiles. | |

| − | + | Labyrinthodonts could be up to four meters long. They were short-legged and large headed. Their skulls were deep and massive, and their jaws were lined with small, sharp, [[conical]] teeth. Also, there was a second row of teeth on the roof of the mouth. In their way of living, labyrinthodonts were probably similar to fishes—it is specultated that they laid eggs in the water, where their [[larvae]] developed into mature animals. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Characteristically labyrinthodonts have [[vertebrae]] made of 4 pieces, an [[intercentrum]], two [[pleurocentra]], and a [[neural arch]]/spine. The relative sizes of these pieces distinguishes different groups of labyrinthodonts. They also appear to have had special sense organs in the skin, that formed a system for perception of water [[fluctuation]]s. Some of them possessed well developed [[gill]]s and many seemingly had primitive lungs. They could breath atmospheric air; that was a great advantage for residents of warm [[shoal]]s with low oxygen levels in the water. The air was inflated into the lungs by contractions of a special throat sac. Primitive members of all labyrinthodont groups were probably true water predators, and only advanced forms that arose independently in different groups and times, gained an amphibious, semi-aquatic mode of living. Their bulky skeleton and their short limbs suggest that the majority of the labyrinthodonts were slow walkers on land. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Classification== | |

| − | + | Amphibians (Class Amphibia) traditionally have been divided into three subclasses: the two extinct subclasses of '''Labyrinthodontia''' and '''[[Lepospondyli]]''' (a small [[Paleozoic]] group), and the extant subclass of '''[[Amphibian|Lissamphibia]]'''. This later subclass includes the three extant orders of [[Anura]] or Salientia ([[frog]]s), [[Salamander|Caudata]] or Urodela ([[salamander]]s, and [[caecilian|Gymnophiona]] or Apoda ([[caecilian]]s. | |

| − | + | However, with the emphasis on [[cladistic]]s, recent taxonomies have tended to discard Labyrinthodontia as being a [[paraphyletic]] group without unique defining features apart from [[plesiomorphy|shared primitive characteristics]]. Classification varies according to the preferred [[phylogeny]] of the author, and whether they use a [[Cladistic#Cladistic classification|stem-based or node-based]] classification. Generally amphibians are defined as the group that includes the common ancestors of all living amphibians (frogs, salamanders, etc) and all their descendants. This may also include extinct groups like the [[temnospondyli|temnospondyls]], which traditionally were placed within the subclass Labyrinthodontia, and the Lepospondyls. ll recent amphibians are included in the Lissamphibia, which is usually considered a [[clade]] (which means that it is thought that all Lissamphibians evolved from a common ancestor apart from other extinct groups), although it has also been suggested also that salamanders arose separately from a temnospondyl-like ancestor (Carroll 2007). | |

| − | The | + | The traditional classification of Labyrinthodoontia (e.g. [[Alfred Sherwood Romer|Romer]] 1966, also repeated in [[Edwin H. Colbert|Colbert]] 1969, and [[Robert L. Carroll|Carroll]] 1988) recognize three orders: |

| + | * Ichthyostegalia — primitive ancestral forms (e.g. ''[[Ichthyostega]]''); Late [[Devonian]] only. | ||

| + | ** ''Now known to be basal tetrapods, not amphibians.'' | ||

| + | * [[Temnospondyli]] — common, small to large, flat-headed forms with either strong or secondarily weak vertebrae and limbs; mainly [[Carboniferous]] to [[Triassic]]. ''[[Eryops]]'' from the early Permian is a well-known [[genus]]. More recently fossil [[Jurassic]] and [[Cretaceous]] temnospondyls have been found. Originally considered ancestral to Anura (frogs), [[Batrachomorpha|may]] or may not be ancestral to [[Lissamphibia|all modern amphibians]] | ||

| + | ** ''Temnospondyls are the only "Labyrinthodonts" currently considered to be true amphibians.'' | ||

| + | * [[Anthracosauria]] — deep skulls, strong vertebrae but weak limbs, evolving towards and ancestral to reptiles; Carboniferous and [[Permian. An example is the genus ''[[Seymouria]]''. | ||

| + | ** ''Now considered to be reptile-like tetrapods separate from true amphibians.'' | ||

| + | A good summary (with diagram) of characteristics and main evolutionary trends of the above three orders is given in Colbert (1969, pp. 102-103). | ||

| − | + | However, as noted above, the grouping Labyrinthodonts has since been largely discarded as paraphyletic; that is, artificially composed of organisms that have separate genealogies, and thus not a valid [[taxon]]. The groups that have usually been placed within Labyrinthodontia are currently variously classified as [[Basal (phylogenetics)|basal]] [[tetrapod]]s, non-amniote [[Reptiliomorpha]]; and as a monophyletic or paraphyletic Temnospondyli, according to [[Cladistics|cladistic analysis]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Temnospondyli are an important and extremely diverse [[taxon]] of small to giant primitive amphibians. They flourished worldwide during the Carboniferous, Permian, and Triassic periods and a few stragglers continued into the [[Cretaceous]]. During their evolutionary history, they adapted to a very wide range of habitats, including fresh-water aquatic, semi-aquatic, amphibious, terrestrial, and in one group even near-shore marine, and their fossil remains have been found on every continent. Authorities disagree over whether some specialized forms were ancestral to some modern amphibians, or whether the whole group died out without leaving any descendants (Benton 2000; Laurin 1996; Reisz n.d.). | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Evolution== | ==Evolution== | ||

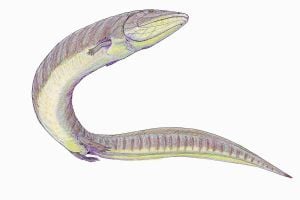

[[Image:Platyoposaurus12DB.jpg|thumb|''[[Platyoposaurus]]'']] | [[Image:Platyoposaurus12DB.jpg|thumb|''[[Platyoposaurus]]'']] | ||

| − | The Labyrinthodontia evolved from a [[Osteichthyes|bony fish]] group | + | The Labyrinthodontia evolved from a [[Osteichthyes|bony fish]] group, the [[Crossopterygii]] [[rhipidistia]]. Nowadays only a few living representatives of these fish remains: two species of [[coelacanth]] and three species of [[lungfish]]. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

The most diverse group of the labyrinthodonts was the [[Batrachomorpha]]. Though these animals looked more like [[crocodile]]s, they most probably gave rise to the order [[Anura]], the amphibians without tails, which include, in particular, the modern frogs. Batrachomorphs appeared in the Late [[Devonian]], but they had worldwide distribution in the continental shallow basins of the [[Permian]] (Platyoposaurus, Melosaurus) and [[Triassic]] Periods ([[Thoosuchus]], [[Benthosuchus]], [[Eryosuchus]]). Some batrachomorphs existed until the end of the [[Cretaceous]]. | The most diverse group of the labyrinthodonts was the [[Batrachomorpha]]. Though these animals looked more like [[crocodile]]s, they most probably gave rise to the order [[Anura]], the amphibians without tails, which include, in particular, the modern frogs. Batrachomorphs appeared in the Late [[Devonian]], but they had worldwide distribution in the continental shallow basins of the [[Permian]] (Platyoposaurus, Melosaurus) and [[Triassic]] Periods ([[Thoosuchus]], [[Benthosuchus]], [[Eryosuchus]]). Some batrachomorphs existed until the end of the [[Cretaceous]]. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

== References == | == References == | ||

| Line 73: | Line 53: | ||

* [[Alfred Sherwood Romer|Romer, A. S.]], (1947, revised ed. 1966) Vertebrate Paleontology, University of Chicago Press, Chicago | * [[Alfred Sherwood Romer|Romer, A. S.]], (1947, revised ed. 1966) Vertebrate Paleontology, University of Chicago Press, Chicago | ||

* [http://people.eku.edu/ritchisong/342notes1.htm Comparative Vertebrate Anatomy] | * [http://people.eku.edu/ritchisong/342notes1.htm Comparative Vertebrate Anatomy] | ||

| + | |||

| + | <ref>[[Michael J. Benton|Benton, M. J.]] (2000), ''Vertebrate Paleontology'', 2nd Ed. [[Blackwell's|Blackwell Science Ltd]] 3rd ed. (2004) - see also [http://palaeo.gly.bris.ac.uk/benton/vertclass.html taxonomic hierarchy of the vertebrates], according to Benton 2004</ref><ref>[[Michel Laurin|Laurin, M.]] (1996) [http://tolweb.org/tree?group=Terrestrial_Vertebrates&contgroup=Sarcopterygii Terrestrial Vertebrates - Stegocephalians: Tetrapods and other digit-bearing vertebrates], [[Tree of Life Web Project|The Tree of Life Web Project]] </ref><ref>[[Robert Reisz|Reisz, Robert]], (no date), [http://www.erin.utoronto.ca/~w3bio356/lectures/temno.html Biology 356 - Major Features of Vertebrate Evolution - The Origin of Tetrapods and Temnospondyls]</ref> | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| Line 80: | Line 62: | ||

[[Category:Life sciences]] | [[Category:Life sciences]] | ||

[[Category:Animals]] | [[Category:Animals]] | ||

| − | {{credit|Labyrinthodontia|166528754}} | + | {{credit|Labyrinthodontia|166528754|Amphibian|168075150|Temnospondyli|166533944}} |

Revision as of 23:56, 30 October 2007

Labyrinthodontia is an extinct, traditional group (superorder or subclass) of amphibians that constituted some of the dominant animals of Late Paleozoic and Early Mesozoic times (about 350 to 210 million years ago). They are considered to include the first vertebrates known to live on solid ground, and to have been ancestral to at least some of the groups of modern amphibians and a bridge to the reptiles (NSMC 2002). Labryinthodonts persisted from the Late Devonian of the Paleozoic into the Late Triassic of the Mesozoic, and flourished in the Carboniferous period (NSMC 2002). The Batrachomorpha, recognized by some as a group of the Labyrinthodontia, are considered even to have persisted until the Cretaceous.

The name Labryinthodonita , which is from the Greek for "maze-toothed," describes the pattern of infolding of the dentine and enamel of the teeth, which are often the only part of the creatures that fossilize. They are also distinguished by a heavy solid skull, and complex vertebrae, the structure of which is useful in older classifications of the group.

Although a traditional and still common designation, this group has fallen out of favor in recent taxonomies because it is paraphyletic—that is, the group does not include all the descendants of the most recent common ancestor.

| Paleozoic era (542 - 251 mya) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cambrian | Ordovician | Silurian | Devonian | Carboniferous | Permian |

| Mesozoic era (251 - 65 mya) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Triassic | Jurassic | Cretaceous |

Description

The amphibians that lived in the Paleozoic traditionally were divided into the two subclasses of Labyrinthodontia and Lepospondyli based on the character of their vertebrae (Panchen 1967). Labyrinthodonts are named for the pattern of infolding of the dentine and enamel of the teeth, that resembles a maze (or labyrinth). They are believed to have representatives that were aquatic, semiaquatic, and terrestrial, and that the passage from aquatic environments to terrestrial took place beginning in the Late Devonian (NSMC 2002). They are considered to be descendant from crossopterygian fishes, and gave rise to the modern amphibians and the reptiles.

Labyrinthodonts could be up to four meters long. They were short-legged and large headed. Their skulls were deep and massive, and their jaws were lined with small, sharp, conical teeth. Also, there was a second row of teeth on the roof of the mouth. In their way of living, labyrinthodonts were probably similar to fishes—it is specultated that they laid eggs in the water, where their larvae developed into mature animals.

Characteristically labyrinthodonts have vertebrae made of 4 pieces, an intercentrum, two pleurocentra, and a neural arch/spine. The relative sizes of these pieces distinguishes different groups of labyrinthodonts. They also appear to have had special sense organs in the skin, that formed a system for perception of water fluctuations. Some of them possessed well developed gills and many seemingly had primitive lungs. They could breath atmospheric air; that was a great advantage for residents of warm shoals with low oxygen levels in the water. The air was inflated into the lungs by contractions of a special throat sac. Primitive members of all labyrinthodont groups were probably true water predators, and only advanced forms that arose independently in different groups and times, gained an amphibious, semi-aquatic mode of living. Their bulky skeleton and their short limbs suggest that the majority of the labyrinthodonts were slow walkers on land.

Classification

Amphibians (Class Amphibia) traditionally have been divided into three subclasses: the two extinct subclasses of Labyrinthodontia and Lepospondyli (a small Paleozoic group), and the extant subclass of Lissamphibia. This later subclass includes the three extant orders of Anura or Salientia (frogs), Caudata or Urodela (salamanders, and Gymnophiona or Apoda (caecilians.

However, with the emphasis on cladistics, recent taxonomies have tended to discard Labyrinthodontia as being a paraphyletic group without unique defining features apart from shared primitive characteristics. Classification varies according to the preferred phylogeny of the author, and whether they use a stem-based or node-based classification. Generally amphibians are defined as the group that includes the common ancestors of all living amphibians (frogs, salamanders, etc) and all their descendants. This may also include extinct groups like the temnospondyls, which traditionally were placed within the subclass Labyrinthodontia, and the Lepospondyls. ll recent amphibians are included in the Lissamphibia, which is usually considered a clade (which means that it is thought that all Lissamphibians evolved from a common ancestor apart from other extinct groups), although it has also been suggested also that salamanders arose separately from a temnospondyl-like ancestor (Carroll 2007).

The traditional classification of Labyrinthodoontia (e.g. Romer 1966, also repeated in Colbert 1969, and Carroll 1988) recognize three orders:

- Ichthyostegalia — primitive ancestral forms (e.g. Ichthyostega); Late Devonian only.

- Now known to be basal tetrapods, not amphibians.

- Temnospondyli — common, small to large, flat-headed forms with either strong or secondarily weak vertebrae and limbs; mainly Carboniferous to Triassic. Eryops from the early Permian is a well-known genus. More recently fossil Jurassic and Cretaceous temnospondyls have been found. Originally considered ancestral to Anura (frogs), may or may not be ancestral to all modern amphibians

- Temnospondyls are the only "Labyrinthodonts" currently considered to be true amphibians.

- Anthracosauria — deep skulls, strong vertebrae but weak limbs, evolving towards and ancestral to reptiles; Carboniferous and [[Permian. An example is the genus Seymouria.

- Now considered to be reptile-like tetrapods separate from true amphibians.

A good summary (with diagram) of characteristics and main evolutionary trends of the above three orders is given in Colbert (1969, pp. 102-103).

However, as noted above, the grouping Labyrinthodonts has since been largely discarded as paraphyletic; that is, artificially composed of organisms that have separate genealogies, and thus not a valid taxon. The groups that have usually been placed within Labyrinthodontia are currently variously classified as basal tetrapods, non-amniote Reptiliomorpha; and as a monophyletic or paraphyletic Temnospondyli, according to cladistic analysis.

Temnospondyli are an important and extremely diverse taxon of small to giant primitive amphibians. They flourished worldwide during the Carboniferous, Permian, and Triassic periods and a few stragglers continued into the Cretaceous. During their evolutionary history, they adapted to a very wide range of habitats, including fresh-water aquatic, semi-aquatic, amphibious, terrestrial, and in one group even near-shore marine, and their fossil remains have been found on every continent. Authorities disagree over whether some specialized forms were ancestral to some modern amphibians, or whether the whole group died out without leaving any descendants (Benton 2000; Laurin 1996; Reisz n.d.).

Evolution

The Labyrinthodontia evolved from a bony fish group, the Crossopterygii rhipidistia. Nowadays only a few living representatives of these fish remains: two species of coelacanth and three species of lungfish.

The most diverse group of the labyrinthodonts was the Batrachomorpha. Though these animals looked more like crocodiles, they most probably gave rise to the order Anura, the amphibians without tails, which include, in particular, the modern frogs. Batrachomorphs appeared in the Late Devonian, but they had worldwide distribution in the continental shallow basins of the Permian (Platyoposaurus, Melosaurus) and Triassic Periods (Thoosuchus, Benthosuchus, Eryosuchus). Some batrachomorphs existed until the end of the Cretaceous.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Carroll, R. L. (1988), Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution, WH Freeman & Co.

- Colbert, E. H., (1969), Evolution of the Vertebrates, John Wiley & Sons Inc (2nd ed.)

- Romer, A. S., (1947, revised ed. 1966) Vertebrate Paleontology, University of Chicago Press, Chicago

- Comparative Vertebrate Anatomy

External links

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

- ↑ Benton, M. J. (2000), Vertebrate Paleontology, 2nd Ed. Blackwell Science Ltd 3rd ed. (2004) - see also taxonomic hierarchy of the vertebrates, according to Benton 2004

- ↑ Laurin, M. (1996) Terrestrial Vertebrates - Stegocephalians: Tetrapods and other digit-bearing vertebrates, The Tree of Life Web Project

- ↑ Reisz, Robert, (no date), Biology 356 - Major Features of Vertebrate Evolution - The Origin of Tetrapods and Temnospondyls