Difference between revisions of "Jihad" - New World Encyclopedia

m (Unlink date links) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (161 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Approved}}{{Copyedited}} |

| − | {{ | + | {{Islam}} |

| − | + | '''Jihad''' ({{lang-ar|جهاد}}) is an Islamic term referring to the religious duty of [[Muslim]]s to strive, or “struggle” in ways related to Islam, both for the sake of internal, spiritual growth, and for the defense and expansion of Islam in the world. In [[Arabic language|Arabic]], the word ''jihād'' is a noun meaning the act of "striving, applying oneself, struggling, persevering."<ref name = kaef2007>Khaled M. Abou El Fadl, ''The Great Theft: Wrestling Islam from the Extremists'' (HarperOne, 2007, ISBN 978-0061189036).</ref> A person engaged in jihad is called a ''[[Mujahideen|mujahid]]'' ({{lang-ar|مجاهد|links=no}}), the plural of which is ''mujahideen'' ({{lang|ar|مجاهدين}}). The word ''jihad'' appears frequently in the [[Qur’an]], often in the idiomatic expression "striving in the way of God ''(al-jihad fi sabil [[Allah]])''", to refer to the act of striving to serve the purposes of God on this earth.<ref name=kaef2007/><ref name="morgan2010"> Diane Morgan, ''Essential Islam: A Comprehensive Guide to Belief and Practice'' (Praeger, 2009, ISBN 978-0313360251).</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | '''Jihad''' ({{lang-ar|جهاد | ||

| − | + | Muslims and scholars do not all agree on its definition.<ref name=UnholyWar>John L. Esposito, ''Unholy War: Terror in the Name of Islam'', (Oxford University Press, 2003, ISBN 978-0195168860).</ref> Many observers—both Muslim and non-Muslim<ref>Rudolph Peters, ''Islam and Colonialism'' (Mouton Publishers, 1980, ISBN 978-9027933478).</ref>—as well as the ''Dictionary of Islam'',<ref name="morgan2010"/> talk of jihad as having two meanings: an inner spiritual struggle (the "greater jihad"), and an outer physical struggle against the enemies of Islam (the "lesser jihad")<ref name="morgan2010"/> which may take a violent or non-violent form.<ref name=kaef2007/> Jihad is often translated as "Holy War,"<ref>Lloyd Steffen, ''Holy War, Just War: Exploring the Moral Meaning of Religious Violence'' (Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2007, ISBN 978-0742558489).</ref> although this term is controversial.<ref>Patricia Crone, ''Medieval Islamic Political Thought'' (Edinburgh University Press, 2006, ISBN 978-0748621941).</ref> | |

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | Jihad is sometimes referred to as the sixth [[Five Pillars of Islam|pillar of Islam]], though it occupies no such official status.<ref>John L. Esposito, ''Islam: The Straight Path'' (Oxford University Press, 2015, ISBN 978-0199381456).</ref> In [[Twelver]] [[Shi'a Islam]], however, jihad is one of the ten [[Practices of the Religion]].<ref name=practices>[http://www.al-islam.org/invitation-to-islam-moustafa-al-qazwini/part-2-islamic-practices Part 2: Islamic Practices] ''al-Islam.org''. Retrieved August 1, 2017.</ref> | ||

| − | + | ==Origins== | |

| + | In [[Literary Arabic|Modern Standard Arabic]], the term ''jihad'' is used to mean struggle for causes, both religious and [[secularism|secular]]. The Hans Wehr ''Dictionary of Modern Written Arabic'' defines the term as "fight, battle; jihad, holy war (against the infidels, as a religious duty)."<ref name=hanswehr>Hans Wehr, ''Arabic-English Dictionary: The Hans Wehr Dictionary of Modern Written Arabic'' (Spoken Language Services, 1993, ISBN 978-0879500030)</ref> Nonetheless, it is usually used in the religious sense and its beginnings are traced back to the [[Qur'an]] and words and actions of the Prophet [[Muhammad]].<ref name="Berkey-2003">Jonathan P. Berkey, ''The Formation of Islam'' (Cambridge University Press, 2003, ISBN 978-0521588133).</ref> In the Qur'an and in later Muslim usage, jihad is commonly followed by the expression ''fi sabil illah'', "in the path of God."<ref> For a listing of all appearances in the Qur'an of jihad and related words, see Hanna E. Kassis, ''A Concordance of the Qur'an'' (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983, ISBN 978-0520043275), 587–588.</ref> [[Muhammad Abdel Haleem]] states that it indicates "the way of truth and justice, including all the teachings it gives on the justifications and the conditions for the conduct of war and peace."<ref>Muhammad Abdel Haleem, ''Understanding the Qur’ān: Themes and Style'' (London: Tauris, 2010, ISBN 978-1845117894), 62.</ref> It is sometimes used without religious connotation, with a meaning similar to the English word "[[crusade]]" (as in "a crusade against drugs").<ref name=OISO>[http://www.oxfordislamicstudies.com/article/opr/t125/e1199 Jihad] ''Oxford Islamic Studies Online''. Retrieved November 20, 2020. </ref> | ||

| − | + | It was generally supposed that the order for a general war could only be given by the [[Caliph]] (an office that was claimed by the Ottoman sultans), but Muslims who did not acknowledge the spiritual authority of the Caliphate (which has been vacant since 1923)—such as non-Sunnis and non-Ottoman Muslim states—always looked to their own rulers for the proclamation of jihad. There has been no overt, universal warfare by Muslims on non-believers since the early caliphate. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Khaled Abou El Fadl stresses that the Islamic theological tradition did not have a notion of "Holy war" (in Arabic ''al-harb al-muqaddasa'') saying this is not an expression used by the Qur’anic text, nor Muslim theologians. In Islamic theology, war is never holy; it is either justified or not. The Qur’an does not use the word ''jihad'' to refer to warfare or fighting; such acts are referred to as ''qital''.<ref name = kaef2007/> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ===Qur’anic use and Arabic forms=== | |

| + | According to Ahmed al-Dawoody, seventeen derivatives of jihād occur altogether forty-one times in eleven [[Meccan surah|Meccan]] texts and thirty [[Medinan surah|Medinan]] ones, with the following five meanings: striving because of religious belief (21), war (12), non-Muslim parents exerting pressure, that is, jihād, to make their children abandon Islam (2), solemn oaths (5), and physical strength (1).<ref name="Al-Dawoody1"> Ahmed Al-Dawoody, ''The Islamic Law of War: Justifications and Regulations'' (Palgrave Macmillan, 2011, ISBN 978-0230111608).</ref> | ||

| − | The | + | ===Hadith=== |

| + | The context of the Qur’an is elucidated by [[Hadith]] (the teachings, deeds and sayings of Prophet Muhammad). Of the 199 references to jihad in perhaps the most standard collection of hadith—[[Sahih Bukhari|Bukhari]]—all assume that jihad means warfare.<ref name=bukhari>Douglas E. Streusand, [http://www.meforum.org/357/what-does-jihad-mean What Does Jihad Mean?] ''Middle East Quarterly'', September 1997, 9–17. Retrieved November 20, 2020.</ref> | ||

| − | + | According to [[Oriental studies|orientalist]] [[Bernard Lewis]], "the overwhelming majority of classical theologians, jurists," and specialists in the [[hadith]] "understood the obligation of jihad in a military sense."<ref name=Lewis-Political>Bernard Lewis, ''The Political Language of Islam'' (University of Chicago Press, 1991, ISBN 978-0226476933).</ref> [[Javed Ahmad Ghamidi]] claims that there is consensus among Islamic scholars that the concept of jihad always includes armed struggle against wrong doers.<ref name="jihad-ghamidi"> Javed Ahmad Ghamidi, [https://www.javedahmedghamidi.org/#!/renaissance/5adb7281b7dd1138372da70b?articleId=5adb728eb7dd1138372da9c7&decade=2020&year=2020 The Islamic Law of Jihad] ''Renaissance'', June 1, 2002. Retrieved November 20, 2020.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Among reported sayings of Prophet Muhammad involving jihad are | |

| − | The word | + | <blockquote>The best Jihad is the word of Justice in front of the oppressive sultan.<ref> Mohammad Hashim Kamali, ''Shari'ah Law: An Introduction'' (Oneworld Publications, 2008, ISBN 978-1851685653).</ref></blockquote> |

| − | + | and | |

| − | |||

| − | + | <blockquote>Ibn Habbaan narrates: The Messenger of Allah was asked about the best jihad. He said: “The best jihad is the one in which your horse is slain and your blood is spilled.” So the one who is killed has practiced the best jihad. <ref>Ibn Nuhaas, [https://web.archive.org/web/20091229051337/http://www.kalamullah.com/Books/MashariAl-AshwaqilaMasarial-Ushaaq-RevisedEdition.pdf ''The Book of Jihad''], translated by Nuur Yamani, 107. Retrieved November 20, 2020.</ref></blockquote> | |

| − | = | + | According to another hadith, supporting one’s parents is also an example of jihad.<ref name="Al-Dawoody1"/> It has also been reported that Prophet Muhammad considered performing [[hajj]] to be the best jihad for Muslim women.<ref name="Al-Dawoody1"/> |

| − | |||

| − | + | ===Evolution of jihad=== | |

| − | + | Some observers have noted evolution in the rules of jihad—from the original “classical” doctrine to that of twenty-first century [[Salafi jihadism]].<ref name=Kadri/><ref name=gorka>Sebastian Gorka, [https://ctc.usma.edu/understanding-historys-seven-stages-of-jihad/ Understanding History’s Seven Stages of Jihad] ''Combating Terrorism Center'', October 3, 2009. Retrieved November 20, 2020. </ref> According to legal historian Sadarat Kadri, in the last couple of centuries incremental changes of Islamic legal doctrine, (developed by Islamists who otherwise condemn any ''[[Bid‘ah]]'' (innovation) in religion), have “normalized” what was once “unthinkable."<ref name=Kadri/> "The very idea that Muslims might blow themselves up for God was unheard of before 1983, and it was not until the early 1990s that anyone anywhere had tried to justify killing innocent Muslims who were not on a battlefield.” <ref name=Kadri/> | |

| − | + | The first or “classical” doctrine of jihad developed towards the end of the eighth century, dwelled on jihad of the sword (''jihad bil-saif'') rather than “jihad of the heart”,<ref name=Lewis-Political/> but had many legal restrictions developed from Qur’an and hadith, such as detailed rules involving “the initiation, the conduct, the termination” of jihad, treatment of prisoners, distribution of booty, etc. Unless there was a sudden attack on the Muslim community, jihad was not a personal obligation (fard ayn) but a collective one (fard al-kifaya),<ref name=Khadduri/> which had to be discharged `in the way of God` (fi sabil Allah), and could only be directed by the caliph, "whose discretion over its conduct was all but absolute."<ref name=Kadri/> (This was designed in part to avoid incidents like the Kharijia’s jihad against and killing of the Caliph Ali, who they judged a non-Muslim.) | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Based on the twentieth century interpretations of [[Sayyid Qutb]], [[Abdullah Azzam]], [[Ruhollah Khomeini]], [[Al-Qaeda]] and others, many if not all of those self-proclaimed jihad fighters believe defensive global jihad is a personal obligation, that no caliph or Muslim head of state need declare. Killing yourself in the process of killing the enemy is an act of martyrdom and brings a special place in heaven, not hell; and the killing of Muslim bystanders, (never mind non-Muslims), should not impede acts of jihad. One analyst described the new interpretation of jihad, the “willful targeting of civilians by a non-state actor through unconventional means.”<ref name=gorka/> | |

| − | == | + | ==History of usage and practice== |

| − | + | The practice of periodic raids by [[Bedouin]] against enemy tribes and settlements to collect spoils predates the revelations of the [[Qur'an]]. It has been suggested that Islamic leaders "instilled into the hearts of the warriors the belief" in jihad "holy war" and ''ghaza'' (raids), but the "fundamental structure" of this Bedouin warfare "remained, ... raiding to collect booty. Thus the standard form of desert warfare, periodic raids by the nomadic tribes against one another and the settled areas, was transformed into a centrally directed military movement and given an ideological rationale."<ref name=johnson-147>James Turner Johnson, ''Holy War Idea in Western and Islamic Traditions'' (Pennsylvania State University Press, 1997, ISBN 978-0271016320).</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[ | + | According to [[Jonathan Berkey]], jihad in the Qur’an was may originally intended against Prophet Muhammad's local enemies, the [[pagan]]s of [[Mecca]] or the [[Jews]] of [[Medina]], but the Qur’anic statements supporting jihad could be redirected once new enemies appeared.<ref name="Berkey-2003"/> |

| − | + | According to another scholar (Majid Khadduri), it was the shift in focus to the conquest and spoils collecting of non-Bedouin unbelievers and away from traditional inter-Bedouin tribal raids, that may have made it possible for Islam not only to expand but to avoid self-destruction.<ref name=Khadduri>Majid Khadduri, ''War and Peace in the Law of Islam'' (Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1955, ISBN 978-0801803369).</ref> | |

| − | Muslim | + | ===Classical=== |

| − | + | "From an early date Muslim law [stated]” that jihad (in the military sense) is "one of the principal obligations" of both "the head of the Muslim state", who declares jihad, and the Muslim community.<ref name=Lewis> Bernard Lewis, ''Islam and the West'' (University Of Chicago Press, 1994, ISBN 978-0195090611).</ref> | |

| − | + | According to legal historian Sadakat Kadri, Islamic jurists first developed classical doctrine of jihad towards the end of the eighth century, using the doctrine of ''[[naskh (tafsir)|naskh]]'' (that God gradually improved His revelations over the course of the Prophet Muhammad's mission) they subordinated verses in the Qur’an emphasizing harmony to the more "confrontational" verses from Prophet Muhammad's later years, and then linked verses on striving (''jihad'') to those of fighting (''qital'').<ref name=Kadri>Sadakat Kadri, ''Heaven on Earth: A Journey Through Shari'a Law from the Deserts of Ancient Arabia to the Streets of the Modern Muslim World'' (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2013, ISBN 978-0374533731).</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Muslim jurists of the eighth century developed a paradigm of international relations that divides the world into three conceptual divisions, dar al-Islam/dar al-‛adl/dar al-salam (house of Islam/house of justice/house of peace), dar al-harb/dar al-jawr (house of war/house of injustice, oppression), and dar al-sulh/dar al-‛ahd/dār al-muwada‛ah (house of peace/house of covenant/house of reconciliation).<ref name="Al-Dawoody1"/> <ref> Hilmi Zawati, ''Is Jihad a Just War?: War, Peace, and Human Rights Under Islamic and Public International Law'' (Edwin Mellen Press, 2002, ISBN 978-0773473041).</ref> The second/eighth century jurist [[Sufyan al-Thawri]] (d. 161/778) headed what [[Majid Khadduri|Khadduri]] calls a pacifist school, which maintained that jihad was only a defensive war,<ref name=Khadduri/><ref name="Al-Dawoody1"/> He also states that the jurists who held this position, among whom he refers to [[Hanafi]] jurists, [[Abd al-Rahman al-Awza'i|al-Awza‛i]] (d. 157/774), [[Malik ibn Anas]] (d. 179/795), and other early jurists, "stressed that tolerance should be shown unbelievers, especially scripturaries and advised the Imam to prosecute war only when the inhabitants of the dar al-harb came into conflict with Islam."<ref name="Al-Dawoody1"/><ref name=Khadduri/> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The duty of Jihad was a collective one (''fard al-kifaya''). It was to be directed only by the caliph who might delayed it when convenient, negotiating truces for up to ten years at a time.<ref name=Kadri/> Within classical [[fiqh|Islamic jurisprudence]] – the development of which is to be dated into the first few centuries after the prophet's death – jihad consisted of wars against unbelievers, [[Apostasy|apostates]], and was the only form of warfare permissible.<ref name=Khadduri/> Another source—[[Bernard Lewis]]—states that fighting rebels and bandits was legitimate though not a form of jihad,<ref name=lewis-crisis>Bernard Lewis, ''The Crisis of Islam: Holy War and Unholy Terror'' (Random House, 2004, ISBN 978-0812967852)</ref> and that while the classical perception and presentation of the jihad was warfare in the field against a foreign enemy, internal jihad "against an infidel renegade, or otherwise illegitimate regime was not unknown."<ref>Bernard Lewis, ''The Middle East: A Brief History of the Last 2,000 Years'' (Scribner, 1997, ISBN 978-0684832807).</ref> | |

| − | + | The primary aim of jihad as warfare is not the conversion of non-Muslims to Islam by force, but rather the expansion and defense of the [[Islamic state]].<ref name=Peters-Medieval>Rudolph Peters, ''Jihad in Medieval and Modern Islam'' (Brill Academic Publishers, 1977, ISBN 978-9004048546).</ref> In theory, jihad was to continue until "all mankind either embraced Islam or submitted to the authority of the Muslim state." There could be truces before this was achieved, but no permanent peace.<ref name=Lewis/> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | One who died 'on the path of God' was a [[martyr]], (''[[Shahid]]''), whose sins were remitted and who was secured "immediate entry to paradise."<ref> [http://qdl.scs-inc.us/2ndParty/Pages/6609.html Islam (1,500)] ''SCS-INC.US''. Retrieved November 20, 2020.</ref> However, some argue [[martyrdom]] is never automatic because it is within God's exclusive province to judge who is worthy of that designation. According to [[Khaled Abou El Fadl]], only God can assess the intentions of individuals and the justness of their cause, and ultimately, whether they deserve the status of being a martyr. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | The Qur’anic text does not recognize the idea of unlimited warfare, and it does not consider the simple fact that one of the belligerents is Muslim to be sufficient to establish the justness of a war. Moreover, according to the Qur'an, war might be necessary, and might even become binding and obligatory, but it is never a moral and ethical good. The Qur'an does not use the word jihad to refer to warfare or fighting; such acts are referred to as ''qital''. While the Qur’an's call to jihad is unconditional and unrestricted, such is not the case for qital. Jihad is a good in and of itself, while qital is not.<ref name = kaef2007/> | |

| − | |||

| − | The | ||

| − | |||

| − | [[ | + | Classical manuals of Islamic jurisprudence often contained a section called ''Book of Jihad'', with [[Rules of war in Islam|rules governing the conduct of war]] covered at great length. Such rules include treatment of nonbelligerents, women, children (also cultivated or residential areas),<ref>Muhammad Hamidullah, ''The Muslim Conduct of State'' (Kazi Publications Inc., 1992, ISBN 978-1567443400).</ref> and division of spoils.<ref name=Bonner>Michael Bonner, ''Jihad in Islamic History: Doctrines and Practice'' (Princeton University Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0691138381).</ref> Such rules offered protection for civilians. Spoils include ''Ghanimah'' (spoils obtained by actual fighting), and ''fai'' (obtained without fighting i.e. when the enemy surrenders or flees).<ref name="chaudhry-spoils">Muhammad Sharif Chaudhry, [http://www.muslimtents.com/shaufi/b17/b176.htm Spoils of War] ''Dynamics of Islamic Jihad''. Retrieved November 20, 2020.</ref> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | The first | + | The first documentation of the law of jihad was written by 'Abd al-Rahman al-Awza'i and [[Muhammad ibn al-Hasan al-Shaybani]]. Although Islamic scholars have differed on the implementation of jihad, there is consensus that the concept of jihad will always include armed struggle against persecution and oppression.<ref name="jihad-ghamidi"/> |

| − | |||

| − | + | As important as jihad was, it was/is not considered one of the "[[Five Pillars of Islam|pillars of Islam]]". According to [[Majid Khadduri]] this is most likely because unlike the pillars of [[Salah|prayer]], [[Sawm|fasting]], and so forth, jihad was a "collective obligation" of the whole Muslim community," (meaning that "if the duty is fulfilled by a part of the community it ceases to be obligatory on others"), and was to be carried out by the Islamic state. This was the belief of "all jurists, with almost no exception", but did not apply to ''defense'' of the Muslim community from a sudden attack, in which case jihad was and "individual obligation" of all believers, including women and children.<ref name=Khadduri/> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ====Early Muslim conquests==== | |

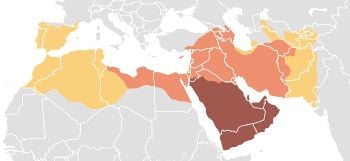

| − | {{ | + | [[Image:Map of expansion of Caliphate.jpg|350px|thumb|right|Age of the [[Caliph]]s {{legend|#a1584e|Expansion under Prophet [[Muhammad]], 622–632/A.H. 1-11}} {{legend|#ef9070|Expansion during the [[Rashidun Empire|Rashidun Caliphate]], 632–661/A.H. 11-40}} {{legend|#fad07d|Expansion during the [[Umayyad Caliphate]], 661–750/A.H. 40-129}}]] |

| − | + | In the early era that inspired classical Islam ([[Rashidun Empire|Rashidun Caliphate]]) and lasted less than a century, “jihad” spread the realm of Islam to include millions of subjects, and an area extending "from the borders of India and China to the Pyrenees and the Atlantic".<ref name=Lewis/> | |

| − | |||

| − | == | + | The role of religion in these early conquests is debated. Medieval Arabic authors believed the conquests were commanded by God, and presented them as orderly and disciplined, under the command of the caliph.<ref name=Bonner/> Many modern historians question whether hunger and desertification, rather than jihad, was a motivating force in the conquests. The famous historian [[William Montgomery Watt]] argued that “Most of the participants in the [early Islamic] expeditions probably thought of nothing more than booty ... There was no thought of spreading the religion of Islam.”<ref name="Al-Dawoody1"/> Similarly, Edward J. Jurji argues that the motivations of the Arab conquests were certainly not “for the propagation of Islam ... Military advantage, economic desires, [and] the attempt to strengthen the hand of the state and enhance its sovereignty ... are some of the determining factors.”<ref name="Al-Dawoody1"/> Some recent explanations cite both material and religious causes in the conquests.<ref name=Bonner/> |

| − | |||

| − | + | ===Post-Classical usage=== | |

| − | + | While most Islamic theologians in the classical period (750–1258 C.E.) understood jihad to be a military endeavor, after Muslim driven conquest stagnated and the caliphate broke up into smaller states the "irresistible and permanent jihad came to an end."<ref name=Lewis-Political/> As jihad became unfeasible it was "postponed from historic to messianic time."<ref name=Lewis-revolt>Bernard Lewis, [https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2001/11/19/the-revolt-of-islam The Revolt of Islam] ''The New Yorker'', November 19, 2001. Retrieved November 20, 2020.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | With the stagnation of Muslim driven expansionism, the concept of jihad became internalized as a moral or spiritual struggle. Later Muslims (in this case modernists such as [[Muhammad Abduh]] and [[Rashid Rida]]) emphasized the defensive aspect of jihad, which was similar to the Western concept of a "[[Just War]]."<ref name=Peters-Classical>Rudolph Peters, ''Jihad in Classical and Modern Islam'' (Markus Wiener Publishers, 2005, ISBN 978-1558763593).</ref> According to historian [[Hamilton Alexander Rosskeen Gibb|Hamilton Gibb]], "in the historic [Muslim] Community the concept of jihad had gradually weakened and at length been largely reinterpreted in terms of Sufi ethics."<ref> Hamilton Alexander Rosskeen Gibb, ''Mohammedanism: An Historical Survey'' (Mentor Books, 1955).</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ===Contemporary fundamentalist usage=== | |

| + | [[File:Fula jihad states map general c1830.png|thumb|250px|The [[Fula jihads|Fulani jihad states]] of West Africa, c. 1830]] | ||

| + | With the [[Islamic revival]], a new "fundamentalist" movement arose, with some different interpretations of Islam, often with an increased emphasis on jihad. The [[Wahhabi]] movement which spread across the Arabian peninsula starting in the eighteenth century, emphasized jihad as armed struggle.<ref name=Gold>Dore Gold, ''Hatred's Kingdom: How Saudi Arabia Supports the New Global Terrorism'' (Regnery Publishing, 2004, ISBN 978-0895260611).</ref> Wars against Western colonial forces were often declared jihad: the Sanusi religious order proclaimed it against [[Italo-Turkish War|Italians in Libya]] in 1912, and the "[[Muhammad Ahmad|Mahdi]]" in the Sudan declared jihad against the British and the Egyptians in 1881. | ||

| − | + | Other early anti-colonial conflicts involving jihad include: | |

| − | + | * [[Padri War]] (1821–1838) | |

| + | * [[Java War]] (1825–1830) | ||

| + | * [[Syed Ahmad Barelvi#Reform/Resistance Movement|Barelvi Mujahidin war]] (1826-1831) | ||

| + | * [[Caucasus War]] (1828–1859) | ||

| + | * [[French rule in Algeria#Resistance of Abd al Qadir|Algerian resistance movement]] (1832 - 1847) | ||

| + | * [[Dervish state|Somali Dervishes]] (1896–1920) | ||

| + | * [[Moro Rebellion]] (1899–1913) | ||

| + | * [[Aceh War]] (1873–1913) | ||

| + | * [[Basmachi Movement]] (1916–1934) | ||

| − | + | None of these jihadist movements were victorious.<ref name=Lewis/> The most powerful, the [[Sokoto Caliphate]], lasted about a century until the British defeated it in 1903. | |

| − | |||

| − | === | + | ====Early Islamism==== |

| − | + | In the twentieth century, many Islamist groups appeared, all having been strongly influenced by the social frustrations following the economic crises of the 1970s and 1980s.<ref>Pippi Van Slooten, “Dispelling Myths about Islam and Jihad”, ''Peace Review'', 17(2) (2005): 289-290.</ref> One of the first Islamist groups, the Muslim Brotherhood, emphasized physical struggle and martyrdom in its credo: "God is our objective; the Qur’an is our constitution; the Prophet is our leader; struggle (jihad) is our way; and death for the sake of God is the highest of our aspirations."<ref name=sacred>Daniel Benjamin and Steven Simon, ''The Age of Sacred Terror: Radical Islam's War Against America'' (Random House, 2003, ISBN 978-0812969849).</ref><ref name=slogan>[https://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/hamas.asp The Covenant of the Islamic Resistance Movement: Article Eight] Hamas Covenant 1988, Yale Law School, Avalon Project. Retrieved November 20, 2020.</ref> In a tract "On Jihad", founder Hasan al-Banna warned readers against "the widespread belief among many Muslims" that struggles of the heart were more demanding than struggles with a sword, and called on Egyptians to prepare for jihad against the British.<ref>Hasan Al-Banna, ''Five Tracts of Hasan Al-Banna, (1906-49): A Selection from the "Majmu'at Rasa'il al-Imam al-Shahid Hasan al-Banna"'' (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1978, ISBN 978-0520095847).</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | According to Rudolph Peters and [[Natana J. DeLong-Bas]], the new "fundamentalist" movement brought a reinterpretation of Islam and their own writings on jihad. These writings tended to be less interested and involved with legal arguments, what the different of schools of Islamic law had to say, or in solutions for all potential situations. "They emphasize more the moral justifications and the underlying ethical values of the rules, than the detailed elaboration of those rules." They also tended to ignore the distinction between Greater and Lesser jihad because it distracted Muslims "from the development of the combative spirit they believe is required to rid the Islamic world of Western influences".<ref name=WahhabiIslam>Natana DeLong-Bas, ''Wahhabi Islam: From Revival and Reform to Global Jihad'' (Oxford University Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0195333015).</ref><ref name=Peters-Classical/> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | In the 1980s the Muslim Brotherhood cleric [[Abdullah Azzam]], sometimes called "the father of the modern global jihad", opened the possibility of successfully waging jihad against unbelievers in the here and now.<ref name=Riedel>Bruce Riedel [https://www.brookings.edu/opinions/the-911-attacks-spiritual-father/ The 9/11 Attacks’ Spiritual Father] ''Brookings'', September 11, 2011. Retrieved November 20, 2020.</ref> Azzam issued a [[fatwa]] calling for jihad against the Soviet occupiers of [[Afghanistan]], declaring it an individual obligation for all able bodied Muslims because it was a defensive jihad to repel invaders. | |

| − | |||

| − | [[ | ||

| − | + | Azzam claimed that "anyone who looks into the state of Muslims today will find that their great misfortune is their abandonment of ''Jihad''", and warned that "without ''Jihad'', ''shirk'' ( the sin of practicing idolatry or polytheism, i.e. the deification or worship of anyone or anything other than the singular God, Allah. ) will spread and become dominant".<ref name=Azzam>Abdullah Azzam, [http://www.religioscope.com/info/doc/jihad/azzam_caravan_3_part1.htm Reasons for Jihad] ''Join the Caravan''. Retrieved November 20, 2020.</ref><ref name=Gold/> Jihad was so important that to "repel" the unbelievers was was "the most important obligation after Iman [faith]."<ref name=Gold/> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Azzam also argued for a broader interpretation of who it was permissible to kill in jihad, an interpretation that some think may have influenced important students of his, including [[Osama bin Laden]].<ref name=Gold/> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | <blockquote>Many Muslims know about the hadith in which the Prophet ordered his companions not to kill any women or children, etc., but very few know that there are exceptions to this case ... In summary, Muslims do not have to stop an attack on mushrikeen, if non-fighting women and children are present.<ref name=Gold/></blockquote> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Having tasted victory in Afghanistan, many of the thousands of fighters returned to their home country such as Egypt, Algeria, Kashmir or to places like Bosnia to continue jihad. Not all the former fighters agreed with Azzam's chioice of targets (Azzam was assassinated in November 1989) but former Afghan fighters led or participated in serious insurgencies in Egypt, Algeria, Kashmir, Somalia in the 1990s and later creating a "transnational jihadist stream."<ref>David Commins, ''The Wahhabi Mission and Saudi Arabia'' (IB Tauris, 2009).</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Contemporary fundamentalists were often influenced by jurist [[Ibn Taymiyya]]'s, and journalist [[Sayyid Qutb]]'s, ideas on jihad. Ibn Taymiyya's hallmark themes included: | |

| − | + | * the permissibility of overthrowing a ruler who is classified as an unbeliever due to a failure to adhere to Islamic law, | |

| − | + | * the absolute division of the world into ''dar al-kufr'' and ''dar al-Islam'', | |

| + | * the labeling of anyone not adhering to one's particular interpretation of Islam as an unbeliever, and | ||

| + | * the call for blanket warfare against non-Muslims, particularly Jews and Christians.<ref name=WahhabiIslam/> | ||

| − | + | Ibn Taymiyya recognized "the possibility of a jihad against `heretical` and `deviant` Muslims within ''dar al-Islam''. He identified as heretical and deviant Muslims anyone who propagated innovations (bida') contrary to the Qur’an and Sunna ... legitimated jihad against anyone who refused to abide by Islamic law or revolted against the true Muslim authorities." He used a very "broad definition" of what constituted aggression or rebellion against Muslims, which would make jihad "not only permissible but necessary."<ref name=WahhabiIslam/> Ibn Taymiyya also paid careful and lengthy attention to the questions of martyrdom and the benefits of jihad: "It is in jihad that one can live and die in ultimate happiness, both in this world and in the Hereafter. Abandoning it means losing entirely or partially both kinds of happiness."<ref name=Peters-Classical/> | |

| − | + | [[File:Qutb.jpg|thumb|right|200px|[[Sayyid Qutb]], Islamist author]] | |

| + | The highly influential Muslim Brotherhood leader, [[Sayyid Qutb]], preached in his book ''Milestones'' that jihad, "is not a temporary phase but a permanent war ... Jihad for freedom cannot cease until the Satanic forces are put to an end and the religion is purified for God in toto."<ref name=Milestones>Sayed Qutb, ''Milestones'' (Islamic Book Service, 2006, ISBN 978-8172312442).</ref><ref name=WahhabiIslam/> Like Ibn Taymiyya, Qutb focused on martyrdom and jihad, but he added the theme of the treachery and enmity towards Islam of Christians and especially Jews. If non-Muslims were waging a "war against Islam", jihad against them was not offensive but defensive. He also insisted that Christians and Jews were ''mushrikeen'' (not monotheists) because (he alleged) gave their priests or rabbis "authority to make laws, obeying laws which were made by them [and] not permitted by God" and "obedience to laws and judgments is a sort of worship"<ref name=Milestones/><ref name=Symon>Fiona Symon, [http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/middle_east/1603178.stm Analysis: The roots of jihad] ''BBC'', September 7, 2014. Retrieved November 20, 2020.</ref> | ||

| − | + | Also influential was Egyptian [[Muhammad abd-al-Salam Faraj]], who wrote the pamphlet ''Al-Farida al-gha'iba'' (Jihad, the Neglected Duty). While Qutb felt that jihad was a proclamation of "liberation for humanity", Farag stressed that jihad would enable Muslims to rule the world and to reestablish the caliphate.<ref> David Cook, ''Understanding Jihad'' (University of California Press, 2015, ISBN 978-0520287327).</ref> He emphasized the importance of fighting the "near enemy"—Muslim rulers he believed to be apostates, such as the president of Egypt, [[Anwar Sadat]], whom his group assassinated—rather than the traditional enemy, Israel. Faraj believed that if Muslims followed their duty and waged jihad, ultimately supernatural divine intervention would provide the victory, a belief he based on Qur'an 9:14. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Shi'a== | |

| − | + | In [[Shi'a Islam]], Jihad is one of the ten [[Practices of the Religion]], (though not one of the five pillars).<ref name=practices/> Traditionally, Twelver Shi'a doctrine has differed from that of [[Sunni]] on the concept of jihad, with jihad being "seen as a lesser priority" in Shi'a theology and "armed activism" by Shi'a being "limited to a person's immediate geography."<ref name=nationalae/> | |

| − | = | + | According to a number of sources, Shi'a doctrine taught that jihad (or at least full scale jihad<ref name=kohlberg/>) can only be carried out under the leadership of the [[Imamah (Shi'a doctrine)|Imam]].<ref name=bukhari/> However, "struggles to defend Islam" are permissible before his return.<ref name=kohlberg>Etan Kohlberg, "The Development of the Imami Shi'i Doctrine of Jihad." ''Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgen Laendischen Gesellschaft'', 126 (1976): 64-86.</ref> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Jihad has been used by Shi'a Islamists in the twentieth Century: Ayatollah [[Ruhollah Khomeini]], the leader of the [[Iranian Revolution]] and founder of the [[Islamic Republic of Iran]], wrote a treatise on the "Greater Jihad" (internal/personal struggle against sin).<ref name=Khomeini-greater>Ruhollah Khomeini, [https://www.al-islam.org/jihad-al-akbar-greatest-jihad-combat-self-sayyid-ruhullah-musawi-khomeini Jihad al-Akbar, The Greatest Jihad: Combat with the Self] Retrieved November 20, 2020.</ref> Khomeini declared jihad on [[Iraq]] in the [[Iran–Iraq War]], and the Shi'a bombers of Western embassies and peacekeeping troops in [[Lebanon]] called themselves, "[[Islamic Jihad Organization|Islamic Jihad]]." | |

| − | + | Until recently jihad did not have the high profile or global significance among Shi'a Islamist that it had among the Sunni.<ref name=nationalae/> This changed with the [[Syrian Civil War]], where, "for the first time in the history of Shi'a Islam, adherents are seeping into another country to fight in a holy war to defend their doctrine."<ref name=nationalae>Hassan Hassan, [https://www.thenationalnews.com/opinion/comment/the-rise-of-shia-jihadism-in-syria-will-fuel-sectarian-fires-1.444963 The rise of Shi'a jihadism in Syria will fuel sectarian fires] ''The National, June 5, 2013. Retrieved November 20, 2020.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Current usage== | |

| − | + | The term 'jihad' has accrued both violent and non-violent meanings. According to [[John Esposito]], it can simply mean striving to live a moral and virtuous life, spreading and defending Islam as well as fighting injustice and oppression, among other things.<ref name=UnholyWar/> The relative importance of these two forms of jihad is a matter of controversy. | |

| − | + | According to scholar of Islam and Islamic history Rudoph Peters, in the contemporary Muslim world, | |

| − | + | *Traditionalist Muslims look to classical works on [[fiqh]]" in their writings on jihad, and "copy phrases" from those; | |

| + | *[[Islamic Modernism|Islamic Modernists]] "emphasize the defensive aspect of jihad, regarding it as tantamount to ''[[Just war theory|bellum justum]]'' in modern international law; and | ||

| + | *Islamist/revivalists/fundamentalists ([[Abul Ala Maududi]], [[Sayyid Qutb]], [[Abdullah Azzam]], etc.) view it as a struggle for the expansion of Islam and the realization of Islamic ideals."<ref name=Peters-Classical/> | ||

| − | + | ===Distinction of "greater" and "lesser" jihad=== | |

| + | In his work, ''The History of Baghdad'', [[Al-Khatib al-Baghdadi]], an 11th-century Islamic scholar, referenced a statement by the [[Sahaba|companion of Prophet Muhammad]] [[Jabir ibn Abd-Allah]]. The reference stated that Jabir said, "We have returned from the lesser jihad (''al-jihad al-asghar'') to the greater jihad (''al-jihad al-akbar'')." When asked, "What is the greater jihad?," he replied, "It is the struggle against oneself."<ref name="bbcislam">[http://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/islam/beliefs/jihad_1.shtml Jihad] ''BBC'', August 3, 2009. Retrieved November 20, 2020.</ref><ref name=bukhari/> This reference gave rise to the distinguishing of two forms of jihad: "greater" and "lesser."<ref name="bbcislam"/> | ||

| − | + | The hadith does not appear in any of the authoritative collections, and according to the Muslim Jurist [[Ibn Hajar al-Asqalani]], the source of the quote is unreliable: | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | <blockquote>This saying is widespread and it is a saying by Ibrahim ibn Ablah according to Nisa'i in al-Kuna. Ghazali mentions it in the Ihya' and al-`Iraqi said that Bayhaqi related it on the authority of Jabir and said: There is weakness in its chain of transmission. | |

| + | :—Hajar al Asqalani, Tasdid al-qaws; see also Kashf al-Khafaa’ (no. 1362)<ref>Shaykh Hisham Kabbani, [http://www.sunnah.org/tasawwuf/jihad004.html Jihad Al Akbar] ''Islamic Beliefs and Doctrine According to Ahl al-Sunna: A Repudiation of "Salafi" Innovations''. Retrieved November 20, 2020.</ref></blockquote> | ||

| − | + | [[Abdullah Azzam]] attacked it as "a false, fabricated hadith which has no basis. It is only a saying of Ibrahim Ibn Abi `Abalah, one of the Successors, and it contradicts textual evidence and reality."<ref name=Azzam/> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Nonetheless, the concept has had "enormous influence" in Islamic mysticism (Sufism).<ref name=bukhari/> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[ | + | [[Hanbali]] scholar [[Ibn Qayyim Al-Jawziyya]] believed that "internal Jihad" is important<ref>G.F. Haddad, [https://www.livingislam.org/n/dgjh_e.html Documentation of "Greater Jihad" hadith] ''Living Islam'', February 28, 2005. Retrieved November 20, 2020. </ref> but suggests those [[hadith]] which consider "Jihad of the heart/soul" to be more important than "Jihad by the sword," are weak.<ref>[http://www.peacewithrealism.org/jihad/jihad03.htm ''Jihad'' in the ''Hadith''], ''Peace with Realism'', April 16, 2006. Retrieved November 20, 2020.</ref> |

| − | + | ===Other spiritual, social, economic struggles=== | |

| − | + | Muslim scholar Mahmoud Ayoub states that "The goal of true ''jihad'' is to attain a harmony between ''islam'' (submission), ''[[Iman (concept)|iman]]'' (faith), and ''[[ihsan]]'' (righteous living)."<ref> Mahmoud M. Ayoub, ''Islam: Faith and History'' (Oneworld Publications, 2005, ISBN 978-1851683505).</ref> | |

| − | + | In modern times, [[Pakistan]]i scholar and professor [[Fazlur Rahman Malik]] has used the term to describe the struggle to establish "just moral-social order",<ref> Fazlur Rahman, ''Major Themes of the Qur’an'' (University Of Chicago Press, 2009, ISBN 978-0226702865). </ref> while President [[Habib Bourguiba]] of [[Tunisia]] has used it to describe the struggle for economic development in that country.<ref name=Peters-Classical/> | |

| − | In | + | A third meaning of jihad is the struggle to build a good society. In a commentary of the hadith [[Sahih Muslim]], entitled al-Minhaj, the [[Islamic Golden Age|medieval Islamic]] scholar [[Yahya ibn Sharaf al-Nawawi]] stated that "one of the collective duties of the community as a whole (fard kifaya) is to lodge a valid protest, to solve problems of religion, to have knowledge of Divine Law, to command what is right and forbid wrong conduct".<ref>Shaykh Hisham Kabbani, Shaykh Seraj Hendricks, and Shaykh Ahmad Hendricks, [http://www.sunnah.org/fiqh/jihad_judicial_ruling.htm Jihad – A Misunderstood Concept from Islam] ''The Muslim Magazine''. Retrieved November 20, 2020.</ref> |

| − | = | + | Majid Khadduri and Ibn Rushd list four kinds of ''jihad fi sabilillah'' (struggle in the cause of God)<ref name="Khadduri"/>: |

| − | * [[ | + | * Jihad of the heart ''(jihad bil qalb/nafs)'' is concerned with combatting [[the devil]] and in the attempt to escape his persuasion to evil. This type of Jihad was regarded as the greater jihad (''al-jihad al-akbar''). |

| − | + | * Jihad by the tongue ''(jihad bil lisan)'' (also Jihad by the word, ''jihad al-qalam'') is concerned with speaking the truth and spreading the word of Islam with one's tongue. | |

| − | * | + | * Jihad by the hand ''(jihad bil yad)'' refers to choosing to do what is right and to combat injustice and what is wrong with action. |

| − | * | + | * Jihad by the sword ''(jihad bis saif)'' refers to ''qital fi sabilillah'' (armed fighting in the way of God, or holy war), the most common usage by [[Salafi]] Muslims and offshoots of the [[Muslim Brotherhood]].<ref name=Khadduri/> |

| − | * [[ | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | Natana J. Delong-Bas lists a number of types of "jihad" that have been proposed by Muslims | |

| − | + | * educational jihad (''jihad al-tarbiyyah''); | |

| − | + | * missionary jihad or calling the people to Islam (''jihad al-da'wah'')<ref name=WahhabiIslam/> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | === | + | ===Warfare:Jihad by the sword (Jihad bil Saif)=== |

| − | + | Whether the Qur'an sanctions defensive warfare only or commands an all-out war against non-Muslims depends on the interpretation of the relevant passages.<ref>Fred M. Donner, ''The Sources of Islamic Conceptions of War'', in James Turner Johnson, ''Just War and Jihad'' (Greenwood Press, 1991).</ref> However, according to the majority of jurists, the Qur’ānic ''[[casus belli]]'' (justification of war) are restricted to aggression against Muslims and ''fitna''—persecution of Muslims because of their religious belief.<ref name="Al-Dawoody1"/> They hold that unbelief in itself is not the justification for war. These jurists therefore maintain that only combatants are to be fought; noncombatants such as women, children, clergy, the aged, the insane, farmers, serfs, the blind, and so on are not to be killed in war. Thus, the Hanafī Ibn Najīm states: "the reason for jihād in our [the Hanafīs] view is ''kawnuhum harbā ‛alaynā'' [literally, their being at war against us]."<ref name="Al-Dawoody1"/> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The Hanafī jurists al-Shaybānī and al-Sarakhsī state that "although kufr [unbelief in God] is one of the greatest sins, it is between the individual and his God the Almighty and the punishment for this sin is to be postponed to the ''dār al-jazā’'', (the abode of reckoning, the Hereafter)."<ref name="Al-Dawoody1"/><ref>Khaled Abou El Fadl, "The Rules of Killing at War: An Inquiry into Classical Sources," ''The Muslim World'' 89(2), (April 1999): 152.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == | + | ==Views of other groups== |

| − | |||

| − | == | + | ===Ahmadiyya=== |

| − | + | In [[Ahmadiyya|Ahmadiyya Islam]], 'Jihad' is a purely religious concept. It is primarily one's personal inner struggle for self-purification. Armed struggle or military exertion is the last option only to be used in defense, to protect religion and one's own life in extreme situations of religious persecution, whilst not being able to follow one's fundamental religious beliefs. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | It is not permissible that jihad be used to spread Islam violently or for political motives, or that it be waged against a government that maintains religious freedom. Political conflicts (even from a defensive stand) over independence, land and resources or reasons other than religious belief cannot be termed jihad. Thus there is a clear distinction, in Ahmadi theology, between Jihad (striving) and ''qitāl'' or ''jihad bil-saif'' (fighting or warfare). While Jihad may involve fighting, not all fighting can be called Jihad. Rather, according to Ahmadiyya belief, ''qitāl'' or military jihad is applicable, as a defensive measure in very strictly defined circumstances and those circumstances do not exist at present. | |

| − | = | + | "Ahmad declared that jihad by the sword had no place in Islam. Instead, he wanted his followers to wage a bloodless, intellectual jihad of the pen to defend Islam."<ref>Siobhain McDonagh, [https://www.theyworkforyou.com/whall/?id=2010-10-20b.284.0 Ahmadiyya Community], Westminster Hall Debate, October 20, 2010. Retrieved November 20, 2020.</ref> |

| − | + | ===Qur’anist=== | |

| + | [[Quranism|Quranists]] do not believe that the word jihad means holy war. They believe it means to struggle, or to strive. They believe it can incorporate both military and non-military aspects. When it refers to the military aspect, it is understood primarily as defensive warfare.<ref>Aisha Y. Musa, [https://www.academia.edu/1236890/Towards_a_Qur_anically_Based_Articulation_of_the_Concept_of_Just_War_ Towards a Qur’anically-Based Articulation of the Concept of “Just War”] ''International Institute of Islamic Thought''. Retrieved November 20, 2020.</ref><ref>Caner Taslaman, ''The Rhetoric of "Terror" and the Rhetoric of "Jihad"'' (Cosmo Publishing, 2020, ISBN 978-1949872361).</ref> | ||

| − | + | == Notes == | |

| − | + | <references/> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | === Islamic | + | ==References== |

| + | * Abou El Fadl, Khaled M. ''The Great Theft: Wrestling Islam from the Extremists''. HarperOne, 2007. ISBN 978-0061189036 | ||

| + | * Al-Banna, Hasan. ''Five Tracts of Hasan Al-Banna, (1906-49): A Selection from the "Majmu'at Rasa'il al-Imam al-Shahid Hasan al-Banna"''. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1978. ISBN 978-0520095847 | ||

| + | * Al-Dawoody, Ahmed. ''The Islamic Law of War: Justifications and Regulations''. Palgrave Macmillan, 2011. ISBN 978-0230111608 | ||

| + | * Ayoub, Mahmoud M. ''Islam: Faith and History''. Oneworld Publications, 2005. ISBN 978-1851683505 | ||

| + | * Benjamin, Daniel, and Steven Simon. ''The Age of Sacred Terror: Radical Islam's War Against America''. Random House, 2003. ISBN 978-0812969849 | ||

| + | * Berkey, Jonathon P. ''The Formation of Islam''. Cambridge University Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0521588133 | ||

| + | * Bonner, Michael. ''Jihad in Islamic History: Doctrines and Practice''. Princeton University Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0691138381 | ||

| + | * Commins, David. ''The Wahhabi Mission and Saudi Arabia''. IB Tauris, 2009. {{ASIN|B008YSQ27K}} | ||

| + | * Cook, David. ''Understanding Jihad''. University of California Press, 2015. ISBN 978-0520287327 | ||

| + | * Crone, Patricia. ''Medieval Islamic Political Thought''. Edinburgh University Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0748621941 | ||

| + | * DeLong-Bas, Natana. ''Wahhabi Islam: From Revival and Reform to Global Jihad''. Oxford University Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0195333015 | ||

| + | * Esposito, John L. ''Unholy War: Terror in the Name of Islam''. Oxford University Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0195168860 | ||

| + | * Esposito, John L. ''Islam: The Straight Path''. Oxford University Press, 2015. ISBN 978-0199381456 | ||

| + | * Gibb, Hamilton Alexander Rosskeen. ''Mohammedanism: An Historical Survey''. Mentor Books, 1955. {{ASIN|B007B4ETVE}} | ||

| + | * Gold, Dore. ''Hatred's Kingdom: How Saudi Arabia Supports the New Global Terrorism''. Regnery Publishing, 2004. ISBN 978-0895260611 | ||

| + | * Haleem, Muhammad Abdel. ''Understanding the Qur’ān: Themes and Style''. London: Tauris, 2010. ISBN 978-1845117894 | ||

| + | * Hamidullah, Muhammad. ''The Muslim Conduct of State''. Kazi Publications Inc., 1992. ISBN 978-1567443400 | ||

| + | * Kadri, Sadakat. ''Heaven on Earth: A Journey Through Shari'a Law from the Deserts of Ancient Arabia to the Streets of the Modern Muslim World''. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2013. ISBN 978-0374533731 | ||

| + | * Kamali, Mohammad Hashim. ''Shari'ah Law: An Introduction''. Oneworld Publications, 2008. ISBN 978-1851685653 | ||

| + | * Kassis, Hanna E. ''A Concordance of the Qur'an''. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983. ISBN 978-0520043275 | ||

| + | * Khadduri, Majid. ''War and Peace in the Law of Islam''. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1955. ISBN 978-0801803369 | ||

| + | * Lewis, Bernard. ''The Political Language of Islam''. University Of Chicago Press, 1991. ISBN 978-0226476933 | ||

| + | * Lewis, Bernard. ''Islam and the West''. University Of Chicago Press, 1994. ISBN 978-0195090611 | ||

| + | * Lewis, Bernard. ''The Middle East: A Brief History of the Last 2,000 Years''. Scribner, 1997. ISBN 978-0684832807 | ||

| + | * Lewis, Bernard. ''The Crisis of Islam: Holy War and Unholy Terror''. Random House, 2004. ISBN 978-0812967852 | ||

| + | * Morgan, Diane. ''Essential Islam: A Comprehensive Guide to Belief and Practice''. Praeger, 2009. ISBN 978-0313360251 | ||

| + | * Peters, Rudolph. ''Islam and Colonialism''. Mouton Publishers, 1980. ISBN 978-9027933478 | ||

| + | * Peters, Rudolph. ''Jihad in Medieval and Modern Islam''. Brill Academic Publishers, 1977. ISBN 978-9004048546 | ||

| + | * Peters, Rudolph. ''Jihad in Classical and Modern Islam''. Markus Wiener Publishers, 2005. ISBN 978-1558763593 | ||

| + | * Qutb, Sayed. ''Milestones''. Islamic Book Service, 2006. ISBN 978-8172312442 | ||

| + | * Rahman, Fazlur. ''Major Themes of the Qur’an''. University Of Chicago Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0226702865 | ||

| + | * Steffen, Lloyd. ''Holy War, Just War: Exploring the Moral Meaning of Religious Violence''. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2007. ISBN 978-0742558489 | ||

| + | * Taslaman, Caner. ''The Rhetoric of "Terror" and the Rhetoric of "Jihad"''. Cosmo Publishing, 2020. ISBN 978-1949872361 | ||

| + | * Zawati, Hilmi. ''Is Jihad a Just War?: War, Peace, and Human Rights Under Islamic and Public International Law''. Edwin Mellen Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0773473041 | ||

| + | * Wehr, Hans. ''Arabic-English Dictionary: The Hans Wehr Dictionary of Modern Written Arabic''. Spoken Language Services, 1993. ISBN 978-0879500030 | ||

| − | All links retrieved | + | == External links == |

| + | All links retrieved August 1, 2022. | ||

| + | *[https://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/islam/beliefs/jihad_1.shtml Jihad] ''BBC: Religions'' | ||

| + | *[http://www.muslim.org/islam/jihad.htm The True Spirit of Jihad] by Sarah Ahmad, ''The Lahore Ahmadiyya Movement'' | ||

| + | *[http://www.aboutjihad.com/jihad/jihad_explained.php What is Jihad?] ''About Jihad'' | ||

| − | + | [[Category:Philosophy and religion]] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[Category:Philosophy and | ||

[[Category:Islam]] | [[Category:Islam]] | ||

| − | + | {{credit|Jihad|717038669}} | |

| − | {{credit| | ||

| − | |||

Latest revision as of 12:39, 1 August 2022

| Part of the series on History of Islam |

| Beliefs and practices |

|

Oneness of God |

| Major figures |

|

Muhammad |

| Texts & law |

|

Qur'an · Hadith · Sharia |

| Branches of Islam |

| Sociopolitical aspects |

|

Art · Architecture |

| See also |

|

Vocabulary of Islam |

Jihad (Arabic: جهاد) is an Islamic term referring to the religious duty of Muslims to strive, or “struggle” in ways related to Islam, both for the sake of internal, spiritual growth, and for the defense and expansion of Islam in the world. In Arabic, the word jihād is a noun meaning the act of "striving, applying oneself, struggling, persevering."[1] A person engaged in jihad is called a mujahid (Arabic: مجاهد), the plural of which is mujahideen (مجاهدين). The word jihad appears frequently in the Qur’an, often in the idiomatic expression "striving in the way of God (al-jihad fi sabil Allah)", to refer to the act of striving to serve the purposes of God on this earth.[1][2]

Muslims and scholars do not all agree on its definition.[3] Many observers—both Muslim and non-Muslim[4]—as well as the Dictionary of Islam,[2] talk of jihad as having two meanings: an inner spiritual struggle (the "greater jihad"), and an outer physical struggle against the enemies of Islam (the "lesser jihad")[2] which may take a violent or non-violent form.[1] Jihad is often translated as "Holy War,"[5] although this term is controversial.[6]

Jihad is sometimes referred to as the sixth pillar of Islam, though it occupies no such official status.[7] In Twelver Shi'a Islam, however, jihad is one of the ten Practices of the Religion.[8]

Origins

In Modern Standard Arabic, the term jihad is used to mean struggle for causes, both religious and secular. The Hans Wehr Dictionary of Modern Written Arabic defines the term as "fight, battle; jihad, holy war (against the infidels, as a religious duty)."[9] Nonetheless, it is usually used in the religious sense and its beginnings are traced back to the Qur'an and words and actions of the Prophet Muhammad.[10] In the Qur'an and in later Muslim usage, jihad is commonly followed by the expression fi sabil illah, "in the path of God."[11] Muhammad Abdel Haleem states that it indicates "the way of truth and justice, including all the teachings it gives on the justifications and the conditions for the conduct of war and peace."[12] It is sometimes used without religious connotation, with a meaning similar to the English word "crusade" (as in "a crusade against drugs").[13]

It was generally supposed that the order for a general war could only be given by the Caliph (an office that was claimed by the Ottoman sultans), but Muslims who did not acknowledge the spiritual authority of the Caliphate (which has been vacant since 1923)—such as non-Sunnis and non-Ottoman Muslim states—always looked to their own rulers for the proclamation of jihad. There has been no overt, universal warfare by Muslims on non-believers since the early caliphate.

Khaled Abou El Fadl stresses that the Islamic theological tradition did not have a notion of "Holy war" (in Arabic al-harb al-muqaddasa) saying this is not an expression used by the Qur’anic text, nor Muslim theologians. In Islamic theology, war is never holy; it is either justified or not. The Qur’an does not use the word jihad to refer to warfare or fighting; such acts are referred to as qital.[1]

Qur’anic use and Arabic forms

According to Ahmed al-Dawoody, seventeen derivatives of jihād occur altogether forty-one times in eleven Meccan texts and thirty Medinan ones, with the following five meanings: striving because of religious belief (21), war (12), non-Muslim parents exerting pressure, that is, jihād, to make their children abandon Islam (2), solemn oaths (5), and physical strength (1).[14]

Hadith

The context of the Qur’an is elucidated by Hadith (the teachings, deeds and sayings of Prophet Muhammad). Of the 199 references to jihad in perhaps the most standard collection of hadith—Bukhari—all assume that jihad means warfare.[15]

According to orientalist Bernard Lewis, "the overwhelming majority of classical theologians, jurists," and specialists in the hadith "understood the obligation of jihad in a military sense."[16] Javed Ahmad Ghamidi claims that there is consensus among Islamic scholars that the concept of jihad always includes armed struggle against wrong doers.[17]

Among reported sayings of Prophet Muhammad involving jihad are

The best Jihad is the word of Justice in front of the oppressive sultan.[18]

and

Ibn Habbaan narrates: The Messenger of Allah was asked about the best jihad. He said: “The best jihad is the one in which your horse is slain and your blood is spilled.” So the one who is killed has practiced the best jihad. [19]

According to another hadith, supporting one’s parents is also an example of jihad.[14] It has also been reported that Prophet Muhammad considered performing hajj to be the best jihad for Muslim women.[14]

Evolution of jihad

Some observers have noted evolution in the rules of jihad—from the original “classical” doctrine to that of twenty-first century Salafi jihadism.[20][21] According to legal historian Sadarat Kadri, in the last couple of centuries incremental changes of Islamic legal doctrine, (developed by Islamists who otherwise condemn any Bid‘ah (innovation) in religion), have “normalized” what was once “unthinkable."[20] "The very idea that Muslims might blow themselves up for God was unheard of before 1983, and it was not until the early 1990s that anyone anywhere had tried to justify killing innocent Muslims who were not on a battlefield.” [20]

The first or “classical” doctrine of jihad developed towards the end of the eighth century, dwelled on jihad of the sword (jihad bil-saif) rather than “jihad of the heart”,[16] but had many legal restrictions developed from Qur’an and hadith, such as detailed rules involving “the initiation, the conduct, the termination” of jihad, treatment of prisoners, distribution of booty, etc. Unless there was a sudden attack on the Muslim community, jihad was not a personal obligation (fard ayn) but a collective one (fard al-kifaya),[22] which had to be discharged `in the way of God` (fi sabil Allah), and could only be directed by the caliph, "whose discretion over its conduct was all but absolute."[20] (This was designed in part to avoid incidents like the Kharijia’s jihad against and killing of the Caliph Ali, who they judged a non-Muslim.)

Based on the twentieth century interpretations of Sayyid Qutb, Abdullah Azzam, Ruhollah Khomeini, Al-Qaeda and others, many if not all of those self-proclaimed jihad fighters believe defensive global jihad is a personal obligation, that no caliph or Muslim head of state need declare. Killing yourself in the process of killing the enemy is an act of martyrdom and brings a special place in heaven, not hell; and the killing of Muslim bystanders, (never mind non-Muslims), should not impede acts of jihad. One analyst described the new interpretation of jihad, the “willful targeting of civilians by a non-state actor through unconventional means.”[21]

History of usage and practice

The practice of periodic raids by Bedouin against enemy tribes and settlements to collect spoils predates the revelations of the Qur'an. It has been suggested that Islamic leaders "instilled into the hearts of the warriors the belief" in jihad "holy war" and ghaza (raids), but the "fundamental structure" of this Bedouin warfare "remained, ... raiding to collect booty. Thus the standard form of desert warfare, periodic raids by the nomadic tribes against one another and the settled areas, was transformed into a centrally directed military movement and given an ideological rationale."[23]

According to Jonathan Berkey, jihad in the Qur’an was may originally intended against Prophet Muhammad's local enemies, the pagans of Mecca or the Jews of Medina, but the Qur’anic statements supporting jihad could be redirected once new enemies appeared.[10]

According to another scholar (Majid Khadduri), it was the shift in focus to the conquest and spoils collecting of non-Bedouin unbelievers and away from traditional inter-Bedouin tribal raids, that may have made it possible for Islam not only to expand but to avoid self-destruction.[22]

Classical

"From an early date Muslim law [stated]” that jihad (in the military sense) is "one of the principal obligations" of both "the head of the Muslim state", who declares jihad, and the Muslim community.[24] According to legal historian Sadakat Kadri, Islamic jurists first developed classical doctrine of jihad towards the end of the eighth century, using the doctrine of naskh (that God gradually improved His revelations over the course of the Prophet Muhammad's mission) they subordinated verses in the Qur’an emphasizing harmony to the more "confrontational" verses from Prophet Muhammad's later years, and then linked verses on striving (jihad) to those of fighting (qital).[20]

Muslim jurists of the eighth century developed a paradigm of international relations that divides the world into three conceptual divisions, dar al-Islam/dar al-‛adl/dar al-salam (house of Islam/house of justice/house of peace), dar al-harb/dar al-jawr (house of war/house of injustice, oppression), and dar al-sulh/dar al-‛ahd/dār al-muwada‛ah (house of peace/house of covenant/house of reconciliation).[14] [25] The second/eighth century jurist Sufyan al-Thawri (d. 161/778) headed what Khadduri calls a pacifist school, which maintained that jihad was only a defensive war,[22][14] He also states that the jurists who held this position, among whom he refers to Hanafi jurists, al-Awza‛i (d. 157/774), Malik ibn Anas (d. 179/795), and other early jurists, "stressed that tolerance should be shown unbelievers, especially scripturaries and advised the Imam to prosecute war only when the inhabitants of the dar al-harb came into conflict with Islam."[14][22]

The duty of Jihad was a collective one (fard al-kifaya). It was to be directed only by the caliph who might delayed it when convenient, negotiating truces for up to ten years at a time.[20] Within classical Islamic jurisprudence – the development of which is to be dated into the first few centuries after the prophet's death – jihad consisted of wars against unbelievers, apostates, and was the only form of warfare permissible.[22] Another source—Bernard Lewis—states that fighting rebels and bandits was legitimate though not a form of jihad,[26] and that while the classical perception and presentation of the jihad was warfare in the field against a foreign enemy, internal jihad "against an infidel renegade, or otherwise illegitimate regime was not unknown."[27]

The primary aim of jihad as warfare is not the conversion of non-Muslims to Islam by force, but rather the expansion and defense of the Islamic state.[28] In theory, jihad was to continue until "all mankind either embraced Islam or submitted to the authority of the Muslim state." There could be truces before this was achieved, but no permanent peace.[24]

One who died 'on the path of God' was a martyr, (Shahid), whose sins were remitted and who was secured "immediate entry to paradise."[29] However, some argue martyrdom is never automatic because it is within God's exclusive province to judge who is worthy of that designation. According to Khaled Abou El Fadl, only God can assess the intentions of individuals and the justness of their cause, and ultimately, whether they deserve the status of being a martyr.

The Qur’anic text does not recognize the idea of unlimited warfare, and it does not consider the simple fact that one of the belligerents is Muslim to be sufficient to establish the justness of a war. Moreover, according to the Qur'an, war might be necessary, and might even become binding and obligatory, but it is never a moral and ethical good. The Qur'an does not use the word jihad to refer to warfare or fighting; such acts are referred to as qital. While the Qur’an's call to jihad is unconditional and unrestricted, such is not the case for qital. Jihad is a good in and of itself, while qital is not.[1]

Classical manuals of Islamic jurisprudence often contained a section called Book of Jihad, with rules governing the conduct of war covered at great length. Such rules include treatment of nonbelligerents, women, children (also cultivated or residential areas),[30] and division of spoils.[31] Such rules offered protection for civilians. Spoils include Ghanimah (spoils obtained by actual fighting), and fai (obtained without fighting i.e. when the enemy surrenders or flees).[32]

The first documentation of the law of jihad was written by 'Abd al-Rahman al-Awza'i and Muhammad ibn al-Hasan al-Shaybani. Although Islamic scholars have differed on the implementation of jihad, there is consensus that the concept of jihad will always include armed struggle against persecution and oppression.[17]

As important as jihad was, it was/is not considered one of the "pillars of Islam". According to Majid Khadduri this is most likely because unlike the pillars of prayer, fasting, and so forth, jihad was a "collective obligation" of the whole Muslim community," (meaning that "if the duty is fulfilled by a part of the community it ceases to be obligatory on others"), and was to be carried out by the Islamic state. This was the belief of "all jurists, with almost no exception", but did not apply to defense of the Muslim community from a sudden attack, in which case jihad was and "individual obligation" of all believers, including women and children.[22]

Early Muslim conquests

In the early era that inspired classical Islam (Rashidun Caliphate) and lasted less than a century, “jihad” spread the realm of Islam to include millions of subjects, and an area extending "from the borders of India and China to the Pyrenees and the Atlantic".[24]

The role of religion in these early conquests is debated. Medieval Arabic authors believed the conquests were commanded by God, and presented them as orderly and disciplined, under the command of the caliph.[31] Many modern historians question whether hunger and desertification, rather than jihad, was a motivating force in the conquests. The famous historian William Montgomery Watt argued that “Most of the participants in the [early Islamic] expeditions probably thought of nothing more than booty ... There was no thought of spreading the religion of Islam.”[14] Similarly, Edward J. Jurji argues that the motivations of the Arab conquests were certainly not “for the propagation of Islam ... Military advantage, economic desires, [and] the attempt to strengthen the hand of the state and enhance its sovereignty ... are some of the determining factors.”[14] Some recent explanations cite both material and religious causes in the conquests.[31]

Post-Classical usage

While most Islamic theologians in the classical period (750–1258 C.E.) understood jihad to be a military endeavor, after Muslim driven conquest stagnated and the caliphate broke up into smaller states the "irresistible and permanent jihad came to an end."[16] As jihad became unfeasible it was "postponed from historic to messianic time."[33]

With the stagnation of Muslim driven expansionism, the concept of jihad became internalized as a moral or spiritual struggle. Later Muslims (in this case modernists such as Muhammad Abduh and Rashid Rida) emphasized the defensive aspect of jihad, which was similar to the Western concept of a "Just War."[34] According to historian Hamilton Gibb, "in the historic [Muslim] Community the concept of jihad had gradually weakened and at length been largely reinterpreted in terms of Sufi ethics."[35]

Contemporary fundamentalist usage

With the Islamic revival, a new "fundamentalist" movement arose, with some different interpretations of Islam, often with an increased emphasis on jihad. The Wahhabi movement which spread across the Arabian peninsula starting in the eighteenth century, emphasized jihad as armed struggle.[36] Wars against Western colonial forces were often declared jihad: the Sanusi religious order proclaimed it against Italians in Libya in 1912, and the "Mahdi" in the Sudan declared jihad against the British and the Egyptians in 1881.

Other early anti-colonial conflicts involving jihad include:

- Padri War (1821–1838)

- Java War (1825–1830)

- Barelvi Mujahidin war (1826-1831)

- Caucasus War (1828–1859)

- Algerian resistance movement (1832 - 1847)

- Somali Dervishes (1896–1920)

- Moro Rebellion (1899–1913)

- Aceh War (1873–1913)

- Basmachi Movement (1916–1934)

None of these jihadist movements were victorious.[24] The most powerful, the Sokoto Caliphate, lasted about a century until the British defeated it in 1903.

Early Islamism

In the twentieth century, many Islamist groups appeared, all having been strongly influenced by the social frustrations following the economic crises of the 1970s and 1980s.[37] One of the first Islamist groups, the Muslim Brotherhood, emphasized physical struggle and martyrdom in its credo: "God is our objective; the Qur’an is our constitution; the Prophet is our leader; struggle (jihad) is our way; and death for the sake of God is the highest of our aspirations."[38][39] In a tract "On Jihad", founder Hasan al-Banna warned readers against "the widespread belief among many Muslims" that struggles of the heart were more demanding than struggles with a sword, and called on Egyptians to prepare for jihad against the British.[40]

According to Rudolph Peters and Natana J. DeLong-Bas, the new "fundamentalist" movement brought a reinterpretation of Islam and their own writings on jihad. These writings tended to be less interested and involved with legal arguments, what the different of schools of Islamic law had to say, or in solutions for all potential situations. "They emphasize more the moral justifications and the underlying ethical values of the rules, than the detailed elaboration of those rules." They also tended to ignore the distinction between Greater and Lesser jihad because it distracted Muslims "from the development of the combative spirit they believe is required to rid the Islamic world of Western influences".[41][34]

In the 1980s the Muslim Brotherhood cleric Abdullah Azzam, sometimes called "the father of the modern global jihad", opened the possibility of successfully waging jihad against unbelievers in the here and now.[42] Azzam issued a fatwa calling for jihad against the Soviet occupiers of Afghanistan, declaring it an individual obligation for all able bodied Muslims because it was a defensive jihad to repel invaders.

Azzam claimed that "anyone who looks into the state of Muslims today will find that their great misfortune is their abandonment of Jihad", and warned that "without Jihad, shirk ( the sin of practicing idolatry or polytheism, i.e. the deification or worship of anyone or anything other than the singular God, Allah. ) will spread and become dominant".[43][36] Jihad was so important that to "repel" the unbelievers was was "the most important obligation after Iman [faith]."[36]

Azzam also argued for a broader interpretation of who it was permissible to kill in jihad, an interpretation that some think may have influenced important students of his, including Osama bin Laden.[36]

Many Muslims know about the hadith in which the Prophet ordered his companions not to kill any women or children, etc., but very few know that there are exceptions to this case ... In summary, Muslims do not have to stop an attack on mushrikeen, if non-fighting women and children are present.[36]

Having tasted victory in Afghanistan, many of the thousands of fighters returned to their home country such as Egypt, Algeria, Kashmir or to places like Bosnia to continue jihad. Not all the former fighters agreed with Azzam's chioice of targets (Azzam was assassinated in November 1989) but former Afghan fighters led or participated in serious insurgencies in Egypt, Algeria, Kashmir, Somalia in the 1990s and later creating a "transnational jihadist stream."[44]

Contemporary fundamentalists were often influenced by jurist Ibn Taymiyya's, and journalist Sayyid Qutb's, ideas on jihad. Ibn Taymiyya's hallmark themes included:

- the permissibility of overthrowing a ruler who is classified as an unbeliever due to a failure to adhere to Islamic law,

- the absolute division of the world into dar al-kufr and dar al-Islam,

- the labeling of anyone not adhering to one's particular interpretation of Islam as an unbeliever, and

- the call for blanket warfare against non-Muslims, particularly Jews and Christians.[41]

Ibn Taymiyya recognized "the possibility of a jihad against `heretical` and `deviant` Muslims within dar al-Islam. He identified as heretical and deviant Muslims anyone who propagated innovations (bida') contrary to the Qur’an and Sunna ... legitimated jihad against anyone who refused to abide by Islamic law or revolted against the true Muslim authorities." He used a very "broad definition" of what constituted aggression or rebellion against Muslims, which would make jihad "not only permissible but necessary."[41] Ibn Taymiyya also paid careful and lengthy attention to the questions of martyrdom and the benefits of jihad: "It is in jihad that one can live and die in ultimate happiness, both in this world and in the Hereafter. Abandoning it means losing entirely or partially both kinds of happiness."[34]

The highly influential Muslim Brotherhood leader, Sayyid Qutb, preached in his book Milestones that jihad, "is not a temporary phase but a permanent war ... Jihad for freedom cannot cease until the Satanic forces are put to an end and the religion is purified for God in toto."[45][41] Like Ibn Taymiyya, Qutb focused on martyrdom and jihad, but he added the theme of the treachery and enmity towards Islam of Christians and especially Jews. If non-Muslims were waging a "war against Islam", jihad against them was not offensive but defensive. He also insisted that Christians and Jews were mushrikeen (not monotheists) because (he alleged) gave their priests or rabbis "authority to make laws, obeying laws which were made by them [and] not permitted by God" and "obedience to laws and judgments is a sort of worship"[45][46]

Also influential was Egyptian Muhammad abd-al-Salam Faraj, who wrote the pamphlet Al-Farida al-gha'iba (Jihad, the Neglected Duty). While Qutb felt that jihad was a proclamation of "liberation for humanity", Farag stressed that jihad would enable Muslims to rule the world and to reestablish the caliphate.[47] He emphasized the importance of fighting the "near enemy"—Muslim rulers he believed to be apostates, such as the president of Egypt, Anwar Sadat, whom his group assassinated—rather than the traditional enemy, Israel. Faraj believed that if Muslims followed their duty and waged jihad, ultimately supernatural divine intervention would provide the victory, a belief he based on Qur'an 9:14.

Shi'a

In Shi'a Islam, Jihad is one of the ten Practices of the Religion, (though not one of the five pillars).[8] Traditionally, Twelver Shi'a doctrine has differed from that of Sunni on the concept of jihad, with jihad being "seen as a lesser priority" in Shi'a theology and "armed activism" by Shi'a being "limited to a person's immediate geography."[48]

According to a number of sources, Shi'a doctrine taught that jihad (or at least full scale jihad[49]) can only be carried out under the leadership of the Imam.[15] However, "struggles to defend Islam" are permissible before his return.[49]

Jihad has been used by Shi'a Islamists in the twentieth Century: Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the leader of the Iranian Revolution and founder of the Islamic Republic of Iran, wrote a treatise on the "Greater Jihad" (internal/personal struggle against sin).[50] Khomeini declared jihad on Iraq in the Iran–Iraq War, and the Shi'a bombers of Western embassies and peacekeeping troops in Lebanon called themselves, "Islamic Jihad."

Until recently jihad did not have the high profile or global significance among Shi'a Islamist that it had among the Sunni.[48] This changed with the Syrian Civil War, where, "for the first time in the history of Shi'a Islam, adherents are seeping into another country to fight in a holy war to defend their doctrine."[48]

Current usage

The term 'jihad' has accrued both violent and non-violent meanings. According to John Esposito, it can simply mean striving to live a moral and virtuous life, spreading and defending Islam as well as fighting injustice and oppression, among other things.[3] The relative importance of these two forms of jihad is a matter of controversy.