Difference between revisions of "Indian reservation" - New World Encyclopedia

Mary Anglin (talk | contribs) |

Mary Anglin (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 65: | Line 65: | ||

In 1887, Congress undertook a significant change in reservation policy by the passage of the [[Dawes Act]], or General Allotment (Severalty) Act. The act ended the general policy of granting land parcels to tribes as-a-whole by granting small parcels of land to individual tribe members. In some cases, for example the [[Umatilla Indian Reservation]], after the individual parcels were granted out of reservation land, the reservation area was reduced by giving the excess land to white settlers. The individual allotment policy continued until 1934, when it was terminated by the [[Indian Reorganization Act]]. | In 1887, Congress undertook a significant change in reservation policy by the passage of the [[Dawes Act]], or General Allotment (Severalty) Act. The act ended the general policy of granting land parcels to tribes as-a-whole by granting small parcels of land to individual tribe members. In some cases, for example the [[Umatilla Indian Reservation]], after the individual parcels were granted out of reservation land, the reservation area was reduced by giving the excess land to white settlers. The individual allotment policy continued until 1934, when it was terminated by the [[Indian Reorganization Act]]. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

Revision as of 03:05, 27 January 2009

An Indian reservation is an area of land managed by a Native American tribe under the United States Department of the Interior's Bureau of Indian Affairs. Because Native American tribes have limited national sovereignty, laws on tribal lands vary from the surrounding area. These laws can permit legal casinos on reservations, which attract tourists.

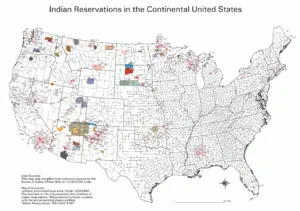

There are about 310 Indian reservations in the United States, meaning not all of the country's 550-plus recognized tribes have a reservation — some tribes have more than one reservation, others have none. In addition, because of past land sales and allotments, discussed below, some reservations are severely fragmented. Each piece of tribal, trust, and privately held land is a separate enclave. This random mixing of private and public real estate can create significant administrative difficulties.

The collective geographical area of all reservations is 55.7 million acres (225,410 km²), representing 2.3% of the area of the United States (2,379,400,204 acres; 9,629,091 km²).

There are twelve Indian reservations that are larger than the state of Rhode Island (776,960 acres; 3,144 km²) and nine reservations larger than Delaware (1,316,480 acres; 5,327 km²). Reservations are unevenly distributed throughout the country with some states having none. Notably, according to the map to the side, Missouri and Arkansas are the only two states that are a part of the contiguous 48 states that are west of the Mississippi without Indian reservations.

The tribal council, not the local or federal government, has jurisdiction over reservations. Different reservations have different systems of government, which may or may not replicate the forms of government found outside the reservation. Some Indian reservations were laid out by the federal government; others were outlined by the states.

At the present time, a slight majority of Native Americans and Alaska Natives live somewhere other than the reservations, often in big western cities such as Phoenix and Los Angeles.

History

Manifest destiny

In order to more fully understand the process through which Native Americans were "placed" in designated lands known as reservations, it is necessary to understand the mentality of white America at that time.

The concept of Manifest Destiny was a nineteenth-century belief that the United States had a mission to expand westward across the North American continent, spreading its form of democracy, freedom, and culture. Many believed the mission to be divinely inspired while others felt it more as an altruistic right to expand the territory of liberty.[1]

Manifest Destiny had serious consequences for Native Americans, since continental expansion usually meant the occupation of Native American land. The United States continued the European practice of recognizing only limited land rights of indigenous peoples. In a policy formulated largely by Henry Knox, Secretary of War in the Washington Administration, the U.S. government sought to expand into the west only through the legal purchase of Native American land in treaties. "Indians" were encouraged to sell their vast tribal lands and become "civilized", which meant (among other things) for Native American men to abandon hunting and become farmers, and for their society to reorganize around the family unit rather than the clan or tribe. Advocates of "civilization" programs believed that the process would greatly reduce the amount of land needed by the Indians, thereby making more land available for purchase by white Americans. Thomas Jefferson believed that while American Indians were the intellectual equals of whites, it was necessary that they live like the whites or inevitably be pushed aside by them. Jefferson's belief, rooted in Enlightenment thinking, which held that whites and Native Americans would merge to create a single nation, did not last his lifetime. Jefferson grew to believe that the natives should emigrate across the Mississippi River and maintain a separate society, an idea made possible by the Louisiana Purchase of 1803.

In the age of Manifest Destiny, this idea, which came to be known as "Indian Removal," gained ground. Although some humanitarian advocates of removal believed that Native tribes would be better off moving away from whites, an increasing number of Americans regarded the natives as nothing more than "savages" who stood in the way of American expansion. As historian Reginald Horsman argued in his influential study Race and Manifest Destiny,[2] racial rhetoric increased during the era of Manifest Destiny. Americans increasingly believed that Native Americans would fade away as the United States expanded. As an example, this idea was reflected in the work of one of America's first great historians, Francis Parkman, whose landmark book The Conspiracy of Pontiac was published in 1851. Parkman wrote that Indians were "destined to melt and vanish before the advancing waves of Anglo-American power, which now rolled westward unchecked and unopposed".[3]

Indian Removal Act

As the new nation expanded westward, the government began acquiring land through the treaty process. There were various reasons the tribes agreed to signing treaties, which in most cases they could not read, and whose translations were often flawed. In many cases, a tribe wanted to appease the government in the hopes of retaining some of their land, and wanted to protect themselves from white harassment. The signing of a treaty often followed a resignation of defeat and served as a last resort effort to bring peace.

In 1823 the Supreme Court handed down a decision (Johnson v. M'Intosh), which stated that Indians could occupy lands within the United States, but could not hold title to those lands. This was because their "right of occupancy" was subordinate to the United States' "right of discovery." [4]

Indian resistance to voluntary removal and a decreasing willingness to sell land via treaty led to the Indian Removal Act, part of a government policy known as Indian removal, which was signed into law by President Andrew Jackson on May 26, 1830.[5]

The Removal Act was strongly supported in the South, where states were eager to gain access to lands inhabited by the "Five Civilized Tribes". (The Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole were considered civilized by white settlers during that time period because they adopted many of the colonists' customs and had generally good relations with their neighbors.) In particular, Georgia was involved in a contentious jurisdictional dispute with the Cherokee nation. President Jackson hoped removal would resolve the Georgia crisis.

The Indian Removal Act was also very controversial. While Indian removal was, in theory, supposed to be voluntary, in practice great pressure was put on Indian leaders to sign removal treaties. Most observers, whether they were in favor of the Indian removal policy or not, realized that the passage of the act meant the inevitable removal of most Indians from the states. Some Native American leaders who had previously resisted removal eventually began to reconsider their positions, especially after Jackson's landslide reelection in 1832.

Most white Americans favored the passage of the Indian Removal Act, though there was significant opposition. Many Christian missionaries, most notably missionary organizer Jeremiah Evarts, agitated against passage of the Act. In Congress, New Jersey Senator Theodore Frelinghuysen and Congressman David Crockett of Tennessee spoke out against the legislation. The Removal Act was passed following bitter debate in Congress.

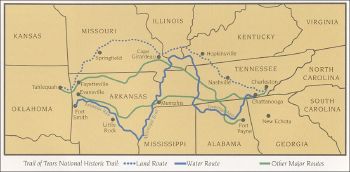

The Removal Act paved the way for the reluctant—and often forcible—emigration of tens of thousands of American Indians to the West. The first removal treaty signed after the Removal Act was the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek on September 27, 1830, in which Choctaws in Mississippi ceded land east of the river in exchange for payment and land in the West. The Treaty of New Echota (signed in 1835) resulted in the removal of the Cherokee via the Trail of Tears. The Seminoles did not leave peacefully as did other tribes; along with fugitive slaves they resisted the removal. The Second Seminole War lasted from 1835 to 1842 and resulted in the forced removal of Seminoles, only a small group of "renegades" remained on or near their traditional lands. Nearly 3,000 were killed during the effort.[6]

Reservation beginnings

In 1851, the United States Congress passed the Indian Appropriations Act which authorized the creation of Indian reservations in modern day Oklahoma. Relations between settlers and natives had grown increasingly worse as the settlers encroached on territory and natural resources in the West.

President Ulysses S. Grant pursued a stated "Peace Policy" as a possible solution to the conflict. The policy included a reorganization of the Indian Service, with the goal of relocating various tribes from their ancestral homes to parcels of lands established specifically for their inhabitation. The policy called for the replacement of government officials by religious men, nominated by churches, to oversee the Indian agencies on reservations in order to teach Christianity to the native tribes. The Quakers were especially active in this policy on reservations. The "civilization" policy was aimed at eventually preparing the tribes for citizenship.[citation needed]

In many cases the lands granted to tribes were hostile to agricultural cultivation, leaving many tribes who accepted the policy in a state bordering on starvation.[citation needed]

Reservation treaties sometimes included stipend agreements, in which the federal government would grant a certain amount of goods to a tribe yearly. The implementation of the policy was erratic, however, and in many cases the stipend goods were not delivered.[citation needed]

Controversy

The policy was controversial from the start. Reservations were generally established by executive order. In many cases, white settlers objected to the size of land parcels, which were subsequently reduced. A report submitted to Congress in 1868 found widespread corruption among the federal Native American agencies and generally poor conditions among the relocated tribes.

Many tribes ignored the relocation orders at first and were forced onto their new limited land parcels. Enforcement of the policy required the United States Army to restrict the movements of various tribes. The pursuit of tribes in order to force them back onto reservations led to a number of Native American Wars. The most well known conflict was the Sioux War on the northern Great Plains, between 1876 and 1881, which included the Battle of Little Bighorn. Other famous wars in this regard included the Nez Perce War.

By the late 1870s, the policy established by President Grant was regarded as a failure, primarily because it had resulted in some of the bloodiest wars between Native Americans and the United States. By 1877, President Rutherford B. Hayes began phasing out the policy, and by 1882 all religious organizations had relinquished their authority to the federal Indian agency.

In 1887, Congress undertook a significant change in reservation policy by the passage of the Dawes Act, or General Allotment (Severalty) Act. The act ended the general policy of granting land parcels to tribes as-a-whole by granting small parcels of land to individual tribe members. In some cases, for example the Umatilla Indian Reservation, after the individual parcels were granted out of reservation land, the reservation area was reduced by giving the excess land to white settlers. The individual allotment policy continued until 1934, when it was terminated by the Indian Reorganization Act.

LOOK UP Allotment Act

Life and culture

Many Native Americans who live on reservations deal with the federal government through two agencies: the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Indian Health Service.

Life qualities in some reservations are comparable to the quality of life in the developing world. For example, Shannon County, South Dakota, home of the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, is routinely described as one of the poorest counties in the nation.

Gambling

In 1979, the Seminole tribe in Florida opened a high-stakes bingo operation on its reservation in Florida. The state attempted to close the operation down but was stopped in the courts. In the 1980s, the case of California v. Cabazon Band of Mission Indians established the right of reservations to operate other forms of gambling operations. In 1988, Congress passed the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act which recognized the right of Native American tribes to establish gambling and gaming facilities on their reservations as long as the states in which they are located have some form of legalized gambling. Today, many Native American casinos are used as tourist attractions to draw visitors and revenue to reservations.

Canada Indian reserve

- For the vast tract created by the Royal Proclamation of 1763 in Canada and the United States see: Indian Reserve (1763)

In Canada, an Indian reserve is specified by the Indian Act as a "tract of land, the legal title to which is vested in Her Majesty, that has been set apart by Her Majesty for the use and benefit of a band." The Act also specifies that land reserved for the use and benefit of a band which is not vested in the Crown (for example, Wikwemikong Unceded Reserve on Manitoulin Island) is also subject to the Indian Act provisions governing reserves. Superficially a reserve is similar to an American Indian reservation, although the histories of the development of reserves and reservations are markedly different. Although the American term reservation is occasionally used, reserve is normally the standard term in Canada.

The terms Native reserve, First Nations reserve and First Nation are also widely used instead of Indian reserve; confusingly, First Nation also designates a group which may occupy more than one reserve. For example, the Munsee-Delaware Nation in Ontario is only one of three reserves in Western Ontario occupied by members of the Munsee-Delaware First Nation. In all, there are over 600 occupied reserves in Canada, most of them quite small in area.

The Indian Act gives the Minister of Indian Affairs the right to "determine whether any purpose for which lands in a reserve are used is for the use and benefit of the band." Title to land within the reserve may only be transferred to the band or to individual band members. Reserve lands may not be seized legally, nor is the personal property of a band or a band member living on a reserve subject to "charge, pledge, mortgage, attachment, levy, seizure distress or execution in favour or at the instance of any person other than an Indian or a band" (section 89 (1) of the Indian Act). As a result reserves and their residents have great difficulty obtaining financing. Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) has, however, created an on-reserve housing loan program in which members of bands which enter into a trust agreement with CMHC and lenders can receive loans to build or repair houses. In other programs loans to residents of reserves are guaranteed by the federal government.

Provinces and municipalities may expropriate reserve land only if specifically authorized by a provincial or federal law. Few reserves have any economic advantages, such as resource revenues. The revenues of those reserves which do are held in trust by the Minister of Indian Affairs. Reserve lands and the personal property of bands and resident band members are exempt from all forms of taxation except local taxation. Corporations owned by members of First Nations are not exempt, however. This exemption has allowed band members operating in proprietorships or partnerships to sell heavily taxed goods such as cigarettes on their reserves at prices considerably lower than those at stores off the reserves. Most reserves are self-governed, within the limits already described, under guidelines established by the Indian Act.

Notes

- ↑ Michael T. Lubragge. March 6, 2003. From Revolution to Reconstruction-Manifest Destiny University of Groningen. Retrieved January 27, 2009.

- ↑ Reginald Horsman. 1981. Race and manifest destiny: the origins of American racial anglo-saxonism. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press. (ISBN 9780674745728)

- ↑ Francis Parkman. 1851. History of the conspiracy of Pontiac, and the War of the North American Tribes against the English Colonies after the Conquest of Canada. Boston: Charles C. Little.

- ↑ Public Broadcasting Service. People & Events: Indian removal, 1814 - 1858 Retrieved January 27, 2009.

- ↑ The U.S. Senate passed the bill on April 24, 1830 (

-19), the U.S. House passed it on May 26, 1830 (102-97); Francis Paul Prucha. 1984. The Great Father: The United States Government and the American Indians, Volume I Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. p 206. - ↑ Eric Foner.2004. Give me liberty!: an American history. New York: W.W. Norton. (ISBN 9780393978728)

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes. The Indian Reorganization Act (W'heeler-Howard Act) - June 18, 1934 Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- Francis, David R. April 23, 2004. Gambling on the Reservation Christian Science Monitor Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- Frazier, Ian. 2000. On the rez. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 9780374226381

- Indian and Northern Affairs, Canada. First Nation Community Profiles Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- O'Neill, Terry. 2002. The Indian reservation system. San Diego: Greenhaven Press. ISBN 9780737707151

- U.S. Census Bureau, Geographic Areas Reference manual. Chapter 5: American Indian and Alaska Native Areas Retrieved January 26, 2009.

External links

All Links Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- BIA full-size map of Indian reservations in the continental United States

- BIA index to map of Indian reservations in the continental United States

- US Census tallies for Indian reservations

- FEMA: Federally recognized Indian reservations

- Tribal Leaders Directory

- Native American Technical Corrections Act of 2003

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.