Wells Barnett, Ida B.

| (37 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | {{epname|Wells Barnett, Ida B.}}{{submitted}}{{approved}}{{copyedited}} | ||

{{Infobox Person | {{Infobox Person | ||

| name = Ida B. Wells | | name = Ida B. Wells | ||

| Line 13: | Line 14: | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | '''Ida Bell Wells''' (July 16, 1862 | + | '''Ida Bell Wells,''' also known as '''Ida B. Wells-Barnett''' (July 16, 1862 - March 25, 1931), was an [[African-American]] journalist, [[civil rights]] activist, and [[women's rights]] leader in the [[women's suffrage]] movement. She is best known for her courageous and effective opposition to [[Lynching in the United States|lynchings]]. |

| − | An articulate and outspoken proponent of equal rights, she became co-owner and editor of ''Free Speech and Headlight'' | + | An articulate and outspoken proponent of equal rights, she became co-owner and editor of ''Free Speech and Headlight,'' an anti-segregationist newspaper based in [[Memphis, Tennessee]]. Wells documented hundreds of lynchings and other atrocities against blacks in her pamphlets ''Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases'' (1892) and ''A Red Record'' (1892). After moving to [[Chicago]] for her own safety, she spoke throughout the [[United States]] and made two trips to [[England]] to bring awareness on the subject. |

| − | + | {{toc}} | |

| − | She helped develop numerous [[African American women]]'s and reform organizations in [[Chicago]] | + | She helped develop numerous [[African American women]]'s and reform organizations in [[Chicago]]. She married Ferdinand L. Barnett, a lawyer, and they had two boys and two girls. One of her greatest accomplishments (with [[Jane Addams]]) was to block the establishment of segregated schools in Chicago. She was a member of the [[Niagara Movement]], and a founding member of the the [[NAACP]]. She published her autobiography, ''Crusade for Justice'' in 1928 and ran for the state legislature in Illinois the year before she died at the age of 68. |

==Biography== | ==Biography== | ||

===Early life=== | ===Early life=== | ||

| − | Ida B. Wells-Barnett was born just before the end of slavery in [[Holly Springs, Mississippi]] on July 16, 1862 to James and Elizabeth "Lizzie Bell" Warrenton Wells, both of whom were [[slave]]s until freed at the end of the [[American Civil War|Civil War]]. At 14, her parents and nine month old brother died of [[yellow fever]] during an epidemic that swept through the South. At a meeting following the funeral, friends and relatives decided to farm out the six remaining Wells children to various aunts and uncles. Ida was devastated by the idea and, to keep the family together, dropped out of [[high school]] and found employment as a teacher in a | + | Ida B. Wells-Barnett was born just before the end of slavery in [[Holly Springs, Mississippi]] on July 16, 1862, to James and Elizabeth "Lizzie Bell" Warrenton Wells, both of whom were [[slave]]s until freed at the end of the [[American Civil War|Civil War]]. At 14, her parents and nine-month-old brother died of [[yellow fever]] during an epidemic that swept through the South. At a meeting following the funeral, friends and relatives decided to farm out the six remaining Wells children to various aunts and uncles. Ida was devastated by the idea and, to keep the family together, dropped out of [[high school]] and found employment as a teacher in a country school for blacks. Despite difficulties, she was able to continue her education by working her way through Rust College in Holly Springs. |

| − | In 1880, Wells moved to [[Memphis, Tennessee|Memphis]] with all of her siblings except for her 15-year-old brother | + | In 1880, Wells moved to [[Memphis, Tennessee|Memphis]] with all of her siblings except for her 15-year-old brother. There she again found work and, when possible, attended summer sessions at [[Fisk University]] in [[Nashville, Tennessee|Nashville]]. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

===Resisting segregation and racism=== | ===Resisting segregation and racism=== | ||

| − | Wells became a public figure in Memphis when, in 1884, she led a campaign against [[racial segregation]] on the local railway. A conductor of the Chesapeake, Ohio & South Western Railroad Company told her to give up her seat on the train to a white man and ordered her into the "[[Jim Crow]]" car, which allowed smoking and was already crowded with other passengers. The federal [[Civil Rights Act of 1875]]—which banned [[discrimination]] on the basis of [[race]], [[creed]], or color in theaters, hotels, transport, and other public accommodations—had just been declared unconstitutional in the ''[[Civil Rights Cases]]'' of 1883, and several railroad companies were able to continue racial segregation of their passengers. Wells found the policy unconscionable and refused to comply. In her [[autobiography]] she explains: | + | [[Image:JimCrowInDurhamNC.jpg|thumb|250px|Laws against racial discrimination were declared unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1875, a situation which lasted until the success of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s.]] |

| − | <blockquote>I refused, saying that the forward car [closest to the locomotive] was a smoker, and as I was in the ladies' car, I proposed to | + | Wells became a public figure in Memphis when, in 1884, she led a campaign against [[racial segregation]] on the local [[railway]]. A conductor of the Chesapeake, Ohio & South Western Railroad Company told her to give up her seat on the train to a white man and ordered her into the "[[Jim Crow]]" car, which allowed smoking and was already crowded with other passengers. The federal [[Civil Rights Act of 1875]]—which banned [[discrimination]] on the basis of [[race]], [[creed]], or color in theaters, hotels, transport, and other public accommodations—had just been declared unconstitutional in the ''[[Civil Rights Cases]]'' of 1883, and several railroad companies were able to continue racial segregation of their passengers. Wells found the policy unconscionable and refused to comply. In her [[autobiography]] she explains: |

| + | <blockquote>I refused, saying that the forward car [closest to the locomotive] was a smoker, and as I was in the ladies' car, I proposed to stay… [The conductor] tried to drag me out of the seat, but the moment he caught hold of my arm I fastened my teeth in the back of his hand. I had braced my feet against the seat in front and was holding to the back, and as he had already been badly bitten he didn't try it again by himself. He went forward and got the baggageman and another man to help him and of course they succeeded in dragging me out.</blockquote> | ||

White passengers applauded as she was dragged out. When she returned to Memphis, she immediately hired an attorney to sue the [[railroad]]. She won her case in the local circuit court, but the railroad company appealed to the [[Supreme Court]] of Tennessee, which reversed the lower court's ruling in 1887. | White passengers applauded as she was dragged out. When she returned to Memphis, she immediately hired an attorney to sue the [[railroad]]. She won her case in the local circuit court, but the railroad company appealed to the [[Supreme Court]] of Tennessee, which reversed the lower court's ruling in 1887. | ||

| − | During her participation in women's suffrage parades, her refusal to stand in the back because she was black resulted in more of her media publicity. Many people wanted to hear from the 25 | + | Wells held strong political opinions, and she upset many people with her views on women's rights. When she was 24, she wrote, "I will not begin at this late day by doing what my soul abhors; sugaring men, weak deceitful creatures, with flattery to retain them as escorts or to gratify a revenge." During her participation in women's suffrage parades, her refusal to stand in the back because she was black resulted in more of her media publicity. Many people wanted to hear from the 25 year old schoolteacher who had stood up to racism. This moved her to begin to tell her story as a journalist. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | ===Anti-lynching campaign=== | ||

| + | [[Image:Lynching-of-woman-1911.jpg|thumb|130px|The lynching of Laura Nelson, May 25, 1911, Okemah, [[Oklahoma]].]] | ||

| + | [[Image:Lynching-of-lige-daniels.jpg|thumb|left|130px|Lynching of Lige Daniels, Center, [[Texas]], August 3, 1920.]] | ||

In 1889, Wells became co-owner and editor of ''Free Speech and Headlight'', an anti-segregationist newspaper based in Memphis on [[Beale Street]], co-owned by Rev. R. Nightingale, pastor of Beale Street [[Baptist Church]]. | In 1889, Wells became co-owner and editor of ''Free Speech and Headlight'', an anti-segregationist newspaper based in Memphis on [[Beale Street]], co-owned by Rev. R. Nightingale, pastor of Beale Street [[Baptist Church]]. | ||

| − | In 1892, three black men named Thomas Moss, Calvin McDowell, and Henry | + | In 1892, three black men named Thomas Moss, Calvin McDowell, and Henry Stewart—owners of a Memphis grocery store which had been taking business away from competing white businesses—were lynched. An angry group of white men had tried to eliminate the competition by attacking the grocery, but the owners fought back, shooting one of the attackers. The grocery owners were arrested, but before a trial could take place, they were lynched by a mob after being dragged away from the jail. Wells wrote strongly about the injustice of the case in ''The Free Speech''. |

| − | In one of her articles she encouraged blacks to leave Memphis, saying, "There | + | In one of her articles she encouraged blacks to leave Memphis, saying, "There is… only one thing left to do; save our money and leave a town which will neither protect our lives and property, nor give us a fair trial in the courts, but takes us out and murders us in cold blood when accused by white persons." Many African-Americans did leave, and others organized boycotts of white-owned businesses. As a result of this and other investigative reporting, Wells' newspaper office was ransacked, and Wells herself had to leave for Chicago. There, she continued to write about Southern lynchings and actively investigated the fraudulent justifications given for them. |

| − | In 1892, Wells also published the famous pamphlet ''Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases'' | + | In 1892, Wells also published the famous pamphlet ''Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases,'' followed by ''A Red Record'' in 1895, documenting her research on [[Lynching in the United States|lynching]]. Having examined many accounts of lynching based on alleged "rape of white women," she concluded that southerners concocted the rape excuse to hide their real reason for lynching black men: Black economic progress, which threatened not only white pocketbooks but also their ideas about black inferiority. [[Frederick Douglass]] expressed approval of Wells' literature: "You have done your people and mine a service… What a revelation of existing conditions your writing has been for me." |

| − | + | ===Move to Chicago=== | |

| + | [[Image:Duluth-lynching-postcard.jpg|thumb|230px|Lynchings in Duluth, [[Minnesota]] in 1920.]] | ||

| − | A few months after founding the Women’s League, the Women’s Loyal Union | + | Upon moving to [[Chicago]], Wells established the ''Alpha Suffrage Club'' and the ''Women's Era Club,'' the first civic organization for African-American women. The name was later changed to the Ida B. Wells Club in honor of its founder. She became a tireless worker for [[Women's suffrage]] and participated in many marches and demonstrations and in the 1913 march for universal suffrage in [[Washington, D.C.]] A few months after founding the Women’s League, the Women’s Loyal Union under the leadership of [[Victoria Matthews]] united 70 women from Brooklyn and Manhattan in support of Wells and her anti-lynching crusade, helping her to finance her 1892 speaking tour of the United States and the [[British Isles]]. |

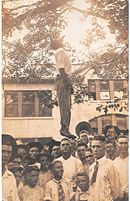

| − | Wells went to Great Britain at the invitation of British Quaker [[Catherine Impey]]. An opponent of [[imperialism]] and supporter of racial equality, Impey wanted to be sure that the British public was informed about the problem of lynching. Although Wells and her speeches—complete with at least one grisly photograph showing grinning white children posing beneath a suspended black | + | Wells went to Great Britain at the invitation of British Quaker [[Catherine Impey]]. An opponent of [[imperialism]] and supporter of racial equality, Impey wanted to be sure that the British public was informed about the problem of lynching. Although Wells and her speeches—complete with at least one grisly photograph showing grinning white children posing beneath a suspended black corpse—caused a stir among doubtful audiences. |

| − | During her second British lecture tour, again arranged by Impey, Wells wrote about her trip for Chicago's ''Daily Inter Ocean'' in a regular column, "Ida B. Wells Abroad." She thus became the first black woman paid to be a correspondent for a mainstream white newspaper | + | During her second British lecture tour, again arranged by Impey, Wells wrote about her trip for Chicago's ''Daily Inter Ocean'' in a regular column, "Ida B. Wells Abroad." She thus became the first black woman paid to be a correspondent for a mainstream white newspaper (Elliott, 242-232). |

| − | ===Boycott, marriage, NAACP and politics=== | + | ===Boycott, marriage, NAACP, and politics=== |

| − | In 1893, | + | [[Image:Frederick Douglass.jpg|thumb|left|150px|[[Frederick Douglass]]]] |

| + | In 1893, Wells and other black leaders, among them [[Frederick Douglass]], organized a boycott of the 1893 [[World's Columbian Exposition]] in Chicago. At the suggestion of white [[abolitionism|abolitionist]] and anti-lynching crusader [[Albion Tourgée]], Wells and her coalition produced a pamphlet entitled ''Why the Colored American Is Not in the World's Columbian Exposition,'' detailing in several languages the workings of southern lynchings and other issues impinging on black Americans. She later reported that 2,000 copies had been distributed at the fair. | ||

| − | In the same year, Tourgée recommended that | + | In the same year, Tourgée recommended that Wells turn to his friend, the black attorney and editor Ferdinand L. Barnett, for pro-bono legal help. Two years later, Barnett and Wells were married. She set an early precedent as being one of the first married American women to keep her own last name along with her husband's. After marrying, Wells stayed home to raise two sons and later two daughters, but she remained active in writing and organizing. |

| − | From 1898 to 1902 | + | From 1898 to 1902, Wells served as secretary of the ''National Afro-American Council,'' and in 1910 she created the ''Negro Fellowship League'' and served as its first president. This organization helped newly arrived migrants from the South. From 1913 to 1916 she was a probation officer for the Chicago municipal court. |

| − | In 1906, Wells joined the [[Niagara Movement]], a black civil rights organization founded | + | In 1906, Wells joined the [[Niagara Movement]], a black civil rights organization founded by [[W.E.B. Du Bois]] and [[William Monroe Trotter]]. When the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was formed in 1909, she was invited to be a member of its "Committee of 40," one of only two African-American women to sign the call to join. Although she was one of the organization's founding members, she was viewed as one of the most radical, opposing the more conservative strategies of [[Booker T. Washington]]. As a result, she was marginalized from positions of leadership in the NAACP. |

| − | After her retirement, | + | One of Wells' greatest accomplishments was to successfully block the establishment of segregated schools in Chicago, working with [[Jane Addams]], the founder of [[Hull House]]. After her retirement, she wrote her autobiography, ''Crusade for Justice'' (1928). By 1930 she became disillusioned with what she felt were the the weak candidates from the major parties to the [[Illinois]] state legislature and decided to run herself. Thus, she became one of the first black women to run for public office in the United States. Within a year she passed away after a lifetime crusading for justice. She died of [[uremia]] in Chicago on March 25, 1931, at the age of 68. |

| + | [[Image:20070601 Wells House (2).JPG|thumb|150px|The Ida B. Wells-Barnett House was her family's residence from 1919 to 1930. It was designated a Chicago Landmark on October 2, 1995.]] | ||

==Legacy== | ==Legacy== | ||

| − | <blockquote> | + | <blockquote>One had better die fighting against injustice than die like a dog or a rat in a trap (Ida B. Wells).</blockquote> |

| − | Throughout her life, Ida B. Wells was unrelenting in her demands for equality and justice for [[African-American]]s and insisted that the African-American community must win justice through its own efforts. Born in slavery, went on to become one of the pioneer activists of the Civil Rights Movement. | + | Throughout her life, Ida B. Wells was unrelenting in her demands for equality and justice for [[African-American]]s and insisted that the African-American community must win justice through its own efforts. Born in slavery, she went on to become one of the pioneer activists of the Civil Rights Movement. In her courageous refusal to give up her seat on public transportation, she anticipated [[Rosa Parks]] by more that 70 years. She was also a women's rights activist, investigative journalist, newspaper editor and publisher, and a co-founder of the NAACP. Wells was the single most effective leader in the campaign to expose and put and end to lynching in the United States. |

| − | On February 1, 1990, the [[United States Postal Service]] issued a 25 cent [[postage stamp]] in her honor. | + | On February 1, 1990, the [[United States Postal Service]] issued a 25-cent [[postage stamp]] in her honor. |

==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| Line 74: | Line 78: | ||

*[[W. E. B. Du Bois]] | *[[W. E. B. Du Bois]] | ||

*[[Jane Addams]] | *[[Jane Addams]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | * Baker, Lee D. [http://www.duke.edu/~ldbaker/classes/AAIH/caaih/ibwells/ibwbkgrd.html ''Ida B. Wells-Barnett (1862-1931) and Her Passion for Justice, Black Women, African American Women, Sufferage, Women's Movement, Civil Rights Leaders''] Retrieved November 30, 2008. | + | * Baker, Lee D. [http://www.duke.edu/~ldbaker/classes/AAIH/caaih/ibwells/ibwbkgrd.html ''Ida B. Wells-Barnett (1862-1931) and Her Passion for Justice, Black Women, African American Women, Sufferage, Women's Movement, Civil Rights Leaders.''] Retrieved November 30, 2008. |

| − | * Elliott, Mark. ''Color-Blind Justice: Albion Tourgée and the Quest for Racial Equality from the Civil War to Plessy v. Ferguson''. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006. ISBN 9780195181395 | + | * Elliott, Mark. ''Color-Blind Justice: Albion Tourgée and the Quest for Racial Equality from the Civil War to Plessy v. Ferguson''. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006. ISBN 9780195181395. |

| − | * Franklin, Vincent P. ''Living Our Stories, Telling Our Truths: Autobiography and the Making of African American Intellectual Tradition''. New York: Scribner, 1995. ISBN 9780689121920 | + | * Franklin, Vincent P. ''Living Our Stories, Telling Our Truths: Autobiography and the Making of African American Intellectual Tradition''. New York: Scribner, 1995. ISBN 9780689121920. |

| − | * Thompson, Mildred I. ''Ida B. Wells-Barnett: | + | * Thompson, Mildred I. ''Ida B. Wells-Barnett: An Exploratory Study of an American Black Woman, 1893-1930'', Brooklyn, NY: Carlson Pub., 1990. ISBN 9780926019218. |

| − | * Townes, Emilie M. ''Womanist Justice, Womanist Hope'' | + | * Townes, Emilie M. ''Womanist Justice, Womanist Hope.'' Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press, 1993. ISBN 9781555406837. |

| − | * Wells, Ida B. and Duster, Alfreda M. ''Crusade for Justice: The Autobiography of Ida B. Wells'' | + | * Wells, Ida B. and Duster, Alfreda M. ''Crusade for Justice: The Autobiography of Ida B. Wells.'' Chicago, 1970. {{OCLC|186020519}}. |

| − | * Wells-Barnett, Ida B. and Royster, Jacqueline Jones (ed.). ''Southern Horrors and Other Writings: The Anti-Lynching Campaign of Ida B. Wells, 1892–1900'' | + | * Wells-Barnett, Ida B. and Royster, Jacqueline Jones (ed.). ''Southern Horrors and Other Writings: The Anti-Lynching Campaign of Ida B. Wells, 1892–1900.'' Boston: Bedford Books, 1997. ISBN 9780312128128. |

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | All links retrieved | + | All links retrieved February 19, 2018. |

*{{gutenberg author| id=Ida+B.+Wells-Barnett | name=Ida B. Wells}} | *{{gutenberg author| id=Ida+B.+Wells-Barnett | name=Ida B. Wells}} | ||

*[http://www.historyisaweapon.com/defcon1/wellslynchlaw.html Lynch Law by Ida B. Wells] | *[http://www.historyisaweapon.com/defcon1/wellslynchlaw.html Lynch Law by Ida B. Wells] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

*[http://lcweb2.loc.gov/ammem/aap/idawells.html Library of Congress, American Memory] | *[http://lcweb2.loc.gov/ammem/aap/idawells.html Library of Congress, American Memory] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

[[Category:biography]] | [[Category:biography]] | ||

| + | [[Category:history and biography]] | ||

[[Category:politicians and reformers]] | [[Category:politicians and reformers]] | ||

| + | [[Category:history of the Americas]] | ||

| + | |||

{{credit|253314470}} | {{credit|253314470}} | ||

Latest revision as of 15:32, 12 February 2024

| Ida B. Wells | |

| |

| Born | July 16 1862 Holly Springs, Mississippi |

|---|---|

| Died | March 25 1931 (aged 68) Chicago, Illinois |

| Education | Fisk University |

| Occupation | Civil rights & Women's rights activist |

| Spouse(s) | Ferdinand L. Barnett |

| Parents | James Wells Elizabeth "Lizzie Bell" Warrenton |

Ida Bell Wells, also known as Ida B. Wells-Barnett (July 16, 1862 - March 25, 1931), was an African-American journalist, civil rights activist, and women's rights leader in the women's suffrage movement. She is best known for her courageous and effective opposition to lynchings.

An articulate and outspoken proponent of equal rights, she became co-owner and editor of Free Speech and Headlight, an anti-segregationist newspaper based in Memphis, Tennessee. Wells documented hundreds of lynchings and other atrocities against blacks in her pamphlets Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases (1892) and A Red Record (1892). After moving to Chicago for her own safety, she spoke throughout the United States and made two trips to England to bring awareness on the subject.

She helped develop numerous African American women's and reform organizations in Chicago. She married Ferdinand L. Barnett, a lawyer, and they had two boys and two girls. One of her greatest accomplishments (with Jane Addams) was to block the establishment of segregated schools in Chicago. She was a member of the Niagara Movement, and a founding member of the the NAACP. She published her autobiography, Crusade for Justice in 1928 and ran for the state legislature in Illinois the year before she died at the age of 68.

Biography

Early life

Ida B. Wells-Barnett was born just before the end of slavery in Holly Springs, Mississippi on July 16, 1862, to James and Elizabeth "Lizzie Bell" Warrenton Wells, both of whom were slaves until freed at the end of the Civil War. At 14, her parents and nine-month-old brother died of yellow fever during an epidemic that swept through the South. At a meeting following the funeral, friends and relatives decided to farm out the six remaining Wells children to various aunts and uncles. Ida was devastated by the idea and, to keep the family together, dropped out of high school and found employment as a teacher in a country school for blacks. Despite difficulties, she was able to continue her education by working her way through Rust College in Holly Springs.

In 1880, Wells moved to Memphis with all of her siblings except for her 15-year-old brother. There she again found work and, when possible, attended summer sessions at Fisk University in Nashville.

Resisting segregation and racism

Wells became a public figure in Memphis when, in 1884, she led a campaign against racial segregation on the local railway. A conductor of the Chesapeake, Ohio & South Western Railroad Company told her to give up her seat on the train to a white man and ordered her into the "Jim Crow" car, which allowed smoking and was already crowded with other passengers. The federal Civil Rights Act of 1875—which banned discrimination on the basis of race, creed, or color in theaters, hotels, transport, and other public accommodations—had just been declared unconstitutional in the Civil Rights Cases of 1883, and several railroad companies were able to continue racial segregation of their passengers. Wells found the policy unconscionable and refused to comply. In her autobiography she explains:

I refused, saying that the forward car [closest to the locomotive] was a smoker, and as I was in the ladies' car, I proposed to stay… [The conductor] tried to drag me out of the seat, but the moment he caught hold of my arm I fastened my teeth in the back of his hand. I had braced my feet against the seat in front and was holding to the back, and as he had already been badly bitten he didn't try it again by himself. He went forward and got the baggageman and another man to help him and of course they succeeded in dragging me out.

White passengers applauded as she was dragged out. When she returned to Memphis, she immediately hired an attorney to sue the railroad. She won her case in the local circuit court, but the railroad company appealed to the Supreme Court of Tennessee, which reversed the lower court's ruling in 1887.

Wells held strong political opinions, and she upset many people with her views on women's rights. When she was 24, she wrote, "I will not begin at this late day by doing what my soul abhors; sugaring men, weak deceitful creatures, with flattery to retain them as escorts or to gratify a revenge." During her participation in women's suffrage parades, her refusal to stand in the back because she was black resulted in more of her media publicity. Many people wanted to hear from the 25 year old schoolteacher who had stood up to racism. This moved her to begin to tell her story as a journalist.

Anti-lynching campaign

In 1889, Wells became co-owner and editor of Free Speech and Headlight, an anti-segregationist newspaper based in Memphis on Beale Street, co-owned by Rev. R. Nightingale, pastor of Beale Street Baptist Church.

In 1892, three black men named Thomas Moss, Calvin McDowell, and Henry Stewart—owners of a Memphis grocery store which had been taking business away from competing white businesses—were lynched. An angry group of white men had tried to eliminate the competition by attacking the grocery, but the owners fought back, shooting one of the attackers. The grocery owners were arrested, but before a trial could take place, they were lynched by a mob after being dragged away from the jail. Wells wrote strongly about the injustice of the case in The Free Speech.

In one of her articles she encouraged blacks to leave Memphis, saying, "There is… only one thing left to do; save our money and leave a town which will neither protect our lives and property, nor give us a fair trial in the courts, but takes us out and murders us in cold blood when accused by white persons." Many African-Americans did leave, and others organized boycotts of white-owned businesses. As a result of this and other investigative reporting, Wells' newspaper office was ransacked, and Wells herself had to leave for Chicago. There, she continued to write about Southern lynchings and actively investigated the fraudulent justifications given for them.

In 1892, Wells also published the famous pamphlet Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases, followed by A Red Record in 1895, documenting her research on lynching. Having examined many accounts of lynching based on alleged "rape of white women," she concluded that southerners concocted the rape excuse to hide their real reason for lynching black men: Black economic progress, which threatened not only white pocketbooks but also their ideas about black inferiority. Frederick Douglass expressed approval of Wells' literature: "You have done your people and mine a service… What a revelation of existing conditions your writing has been for me."

Move to Chicago

Upon moving to Chicago, Wells established the Alpha Suffrage Club and the Women's Era Club, the first civic organization for African-American women. The name was later changed to the Ida B. Wells Club in honor of its founder. She became a tireless worker for Women's suffrage and participated in many marches and demonstrations and in the 1913 march for universal suffrage in Washington, D.C. A few months after founding the Women’s League, the Women’s Loyal Union under the leadership of Victoria Matthews united 70 women from Brooklyn and Manhattan in support of Wells and her anti-lynching crusade, helping her to finance her 1892 speaking tour of the United States and the British Isles.

Wells went to Great Britain at the invitation of British Quaker Catherine Impey. An opponent of imperialism and supporter of racial equality, Impey wanted to be sure that the British public was informed about the problem of lynching. Although Wells and her speeches—complete with at least one grisly photograph showing grinning white children posing beneath a suspended black corpse—caused a stir among doubtful audiences.

During her second British lecture tour, again arranged by Impey, Wells wrote about her trip for Chicago's Daily Inter Ocean in a regular column, "Ida B. Wells Abroad." She thus became the first black woman paid to be a correspondent for a mainstream white newspaper (Elliott, 242-232).

Boycott, marriage, NAACP, and politics

In 1893, Wells and other black leaders, among them Frederick Douglass, organized a boycott of the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago. At the suggestion of white abolitionist and anti-lynching crusader Albion Tourgée, Wells and her coalition produced a pamphlet entitled Why the Colored American Is Not in the World's Columbian Exposition, detailing in several languages the workings of southern lynchings and other issues impinging on black Americans. She later reported that 2,000 copies had been distributed at the fair.

In the same year, Tourgée recommended that Wells turn to his friend, the black attorney and editor Ferdinand L. Barnett, for pro-bono legal help. Two years later, Barnett and Wells were married. She set an early precedent as being one of the first married American women to keep her own last name along with her husband's. After marrying, Wells stayed home to raise two sons and later two daughters, but she remained active in writing and organizing.

From 1898 to 1902, Wells served as secretary of the National Afro-American Council, and in 1910 she created the Negro Fellowship League and served as its first president. This organization helped newly arrived migrants from the South. From 1913 to 1916 she was a probation officer for the Chicago municipal court.

In 1906, Wells joined the Niagara Movement, a black civil rights organization founded by W.E.B. Du Bois and William Monroe Trotter. When the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was formed in 1909, she was invited to be a member of its "Committee of 40," one of only two African-American women to sign the call to join. Although she was one of the organization's founding members, she was viewed as one of the most radical, opposing the more conservative strategies of Booker T. Washington. As a result, she was marginalized from positions of leadership in the NAACP.

One of Wells' greatest accomplishments was to successfully block the establishment of segregated schools in Chicago, working with Jane Addams, the founder of Hull House. After her retirement, she wrote her autobiography, Crusade for Justice (1928). By 1930 she became disillusioned with what she felt were the the weak candidates from the major parties to the Illinois state legislature and decided to run herself. Thus, she became one of the first black women to run for public office in the United States. Within a year she passed away after a lifetime crusading for justice. She died of uremia in Chicago on March 25, 1931, at the age of 68.

Legacy

One had better die fighting against injustice than die like a dog or a rat in a trap (Ida B. Wells).

Throughout her life, Ida B. Wells was unrelenting in her demands for equality and justice for African-Americans and insisted that the African-American community must win justice through its own efforts. Born in slavery, she went on to become one of the pioneer activists of the Civil Rights Movement. In her courageous refusal to give up her seat on public transportation, she anticipated Rosa Parks by more that 70 years. She was also a women's rights activist, investigative journalist, newspaper editor and publisher, and a co-founder of the NAACP. Wells was the single most effective leader in the campaign to expose and put and end to lynching in the United States.

On February 1, 1990, the United States Postal Service issued a 25-cent postage stamp in her honor.

See also

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Baker, Lee D. Ida B. Wells-Barnett (1862-1931) and Her Passion for Justice, Black Women, African American Women, Sufferage, Women's Movement, Civil Rights Leaders. Retrieved November 30, 2008.

- Elliott, Mark. Color-Blind Justice: Albion Tourgée and the Quest for Racial Equality from the Civil War to Plessy v. Ferguson. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006. ISBN 9780195181395.

- Franklin, Vincent P. Living Our Stories, Telling Our Truths: Autobiography and the Making of African American Intellectual Tradition. New York: Scribner, 1995. ISBN 9780689121920.

- Thompson, Mildred I. Ida B. Wells-Barnett: An Exploratory Study of an American Black Woman, 1893-1930, Brooklyn, NY: Carlson Pub., 1990. ISBN 9780926019218.

- Townes, Emilie M. Womanist Justice, Womanist Hope. Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press, 1993. ISBN 9781555406837.

- Wells, Ida B. and Duster, Alfreda M. Crusade for Justice: The Autobiography of Ida B. Wells. Chicago, 1970. OCLC 186020519.

- Wells-Barnett, Ida B. and Royster, Jacqueline Jones (ed.). Southern Horrors and Other Writings: The Anti-Lynching Campaign of Ida B. Wells, 1892–1900. Boston: Bedford Books, 1997. ISBN 9780312128128.

External links

All links retrieved February 19, 2018.

- Works by Ida B. Wells. Project Gutenberg

- Lynch Law by Ida B. Wells

- Library of Congress, American Memory

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.