Difference between revisions of "Guru and Disciple" - New World Encyclopedia

Scott Dunbar (talk | contribs) m (→Bhakti yoga) |

|||

| (15 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Copyedited}}{{Approved}}{{Submitted}}{{Paid}} |

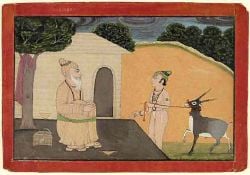

| + | [[File:Guru and DiscipleI.jpg|thumb|250px|"Guru and Disciple" ca. 1740]] | ||

| + | In several Eastern religions (such as [[Hinduism]], [[Tantra]], [[Zen]] and [[Sikhism]]), the '''Guru-Disciple relationship''' plays a critically important role in the process of transmitting religious teachings. This method of teaching is considered to be one of the best ways to communicate and impart sacred (and sometimes secret) religious truths. In Hinduism, the Guru-disciple relationship is called the ''guru-shishya tradition,'' involving in one-way flow of deeply important religious knowledge from a ''[[guru]]'' (teacher, {{lang | hi | गुरू}}) to a {{unicode|'śiṣya'}} (disciple, {{lang | hi | शिष्य}}) or ''chela''. Such sharing of sacred wisdom is imparted through the formal relationship between the guru and the disciple that has many requirements including extreme respect towards the guru, and unwavering commitment, devotion and obedience in the student. In some forms of [[Buddhism]], the Guru-disciple relationship is called "dharma transmission." | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | The Guru-Disciple relationship has provided an effective mechanism for sharing the spiritual riches of Eastern religions in a deeply personal and meaningful way; however, due to the extreme devotion and loyalty toward the Guru, there is always the potential for abuse. Unfortunately, there have been many reported cases where fraudulent gurus have taken advantage of their disciples in various ways, including [[sexual abuse]]. | ||

| − | + | ==Hinduism== | |

| − | + | Beginning in the early oral traditions of the ''[[Upanishads]]'' (c. 2000 B.C.E.), the guru-shishya relationship evolved into a fundamental component of [[Hinduism]]. The term Upanishad itself is derived from the [[Sanskrit]] words ''upa'' (near), ''ni'' (down) and şad (to sit) meaning "sitting next to" a spiritual teacher to receive instruction. Such instruction is also exemplified by the relationship between [[Krishna]] and [[Arjuna]] in the ''[[Bhagavad Gita]]'' portion of the ''[[Mahabharata]]'', and between [[Rama]] and [[Hanuman]] in the ''[[Ramayana]].'' In the Upanishads, gurus and shishya appear in a variety of settings (a husband answering questions about immortality, a teenage boy being taught by [[Yama]], etc.) Sometimes the [[sage]]s are women, and the instructions may be sought by kings. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == | ||

| − | Beginning in the early oral traditions of the ''[[Upanishads]]'' (c. 2000 B.C.E.), the guru-shishya relationship | ||

In the [[Vedas]], the ''brahmavidya'' or knowledge of [[Brahman]] is communicated from guru to shishya by oral lore. | In the [[Vedas]], the ''brahmavidya'' or knowledge of [[Brahman]] is communicated from guru to shishya by oral lore. | ||

| − | == | + | ==Features of the Guru-disciple relationship== |

| − | |||

Within the broad spectrum of the Hindu religion, the guru-shishya relationship can be found in numerous variant forms including [[Tantra]]. Some common elements in this relationship include: | Within the broad spectrum of the Hindu religion, the guru-shishya relationship can be found in numerous variant forms including [[Tantra]]. Some common elements in this relationship include: | ||

| Line 19: | Line 18: | ||

* Gurudakshina, where the ''shishya'' gives a gift to the ''guru'' as a token of gratitude, often the only monetary or otherwise fee that the student ever gives. Such tokens can be as simple as a piece of fruit or as serious as a thumb, as in the case of ''Ekalavya'' and his guru ''Dronacharya''. | * Gurudakshina, where the ''shishya'' gives a gift to the ''guru'' as a token of gratitude, often the only monetary or otherwise fee that the student ever gives. Such tokens can be as simple as a piece of fruit or as serious as a thumb, as in the case of ''Ekalavya'' and his guru ''Dronacharya''. | ||

| − | ==Guru- | + | ==Guru-Disciple relationship types== |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

===Śruti tradition === | ===Śruti tradition === | ||

| + | The Guru-shishya tradition plays an important part in the [[Shruti]] tradition of Vaidika dharma. The Hindus believe that the [[Vedas]] have been handed down through the ages from [[Guru]] to shishya. The Vedas themselves prescribe for a young brahmachari to be sent to a Gurukul where the Guru (referred to also as [[acharya]]) teaches the pupil the Vedas and [[Vedangas]]. The term of stay varies (''[[Manu Smriti]]'' says the term may be 12 years, 36 years or 48 years). Following the stay at the Guruku, the brahmachari returns home after performing a ceremony called samavartana. | ||

| − | + | The word Śrauta is derived from the word Śruti meaning that which is heard. The Śrauta tradition is a purely oral handing down of the Vedas, but many modern Vedic scholars make use of books as a teaching tool.<ref>[http://www.kamakoti.org/hindudharma/part17/chap1.htm Hindu Dharma] Retrieved June 15, 2020.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | The word Śrauta is derived from the word Śruti meaning that which is heard. The Śrauta tradition is a purely oral handing down of the Vedas, but many modern Vedic scholars make use of books as a teaching tool.<ref>[http://www.kamakoti.org/hindudharma/part17/chap1.htm Hindu Dharma]</ref> | ||

===Bhakti yoga=== | ===Bhakti yoga=== | ||

| − | + | The best known form of the Guru-shishya relationship is found in the practice of [[bhakti]] ([[Sanskrit]]: "Devotion" or "surrender to [[God]]). Bhakti extends from the simplest expression of devotion to the ego-decimating principle of [[prapati]], which is total surrender. The bhakti form of the guru-shishya relationship generally incorporates three primary practices: | |

| − | The best known form of the Guru-shishya relationship is the [[bhakti]] | ||

# Devotion to the guru as a divine figure or [[avatar]]. | # Devotion to the guru as a divine figure or [[avatar]]. | ||

| Line 45: | Line 32: | ||

==== Prapatti ==== | ==== Prapatti ==== | ||

| − | + | In the ego-decimating principle of prapatti (Sanskrit, "Throwing oneself down"), the level of the submission of the will of the shishya to the will of the guru is sometimes extreme. It is one of total, unconditional submission to God or guru, often coupled with an attitude of self-effacement. This doctrine is perhaps best expressed in the teachings of the four Samayacharya saints, who shared a profound and mystical love of Siva that included: | |

| − | In the ego-decimating principle of prapatti (Sanskrit, "Throwing oneself down"), the level of the submission of the will of the shishya to the will of the guru is sometimes extreme. It is one of total, unconditional submission to God or guru, often coupled with an attitude of | ||

* Deep humility and self-effacement, admission of [[sin]] and weakness | * Deep humility and self-effacement, admission of [[sin]] and weakness | ||

| Line 53: | Line 39: | ||

In its most extreme form it sometimes includes: | In its most extreme form it sometimes includes: | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

* The requirement that the shishya engage in various forms of physical demonstrations of affection towards the guru, such as bowing, kissing the hands or feet of the guru, and sometimes agreeing to various physical punishments as may sometimes be ordered by the guru. | * The requirement that the shishya engage in various forms of physical demonstrations of affection towards the guru, such as bowing, kissing the hands or feet of the guru, and sometimes agreeing to various physical punishments as may sometimes be ordered by the guru. | ||

* Sometimes the authority of the guru will extend to all aspects of the shishya's life, including sexuality, livelihood, social life, etc. | * Sometimes the authority of the guru will extend to all aspects of the shishya's life, including sexuality, livelihood, social life, etc. | ||

Often a guru will assert that he or she is capable of leading a shishya directly to the highest possible state of spirituality or consciousness, sometimes referred to within Hinduism as [[moksha]]. In the bhakti guru-shishya relationship the guru is often believed to have supernatural powers, leading to the deification of the guru. | Often a guru will assert that he or she is capable of leading a shishya directly to the highest possible state of spirituality or consciousness, sometimes referred to within Hinduism as [[moksha]]. In the bhakti guru-shishya relationship the guru is often believed to have supernatural powers, leading to the deification of the guru. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Advaita Vedanta=== | ||

| + | [[Advaita|Advaita vedānta]] requires anyone seeking to study advaita vedānta to do so from a [[Guru]] ''(teacher)''. The Guru must have the following qualities (see Mundaka Upanishad 1.2.12): | ||

| + | #Śrotriya—must be learned in the [[Vedas|Vedic scriptures]] and sampradaya | ||

| + | #Brahmanişţha—literally meaning ''established in [[Brahman]]''; must have ''realized'' the oneness of Brahman in everything and in himself. | ||

| + | The seeker must serve the Guru and submit his questions with all humility so that doubt may be removed (see [[Bhagavad Gita]] 4.34). | ||

=== In Buddhism === | === In Buddhism === | ||

| − | + | ''Dharma transmission'' ([[Chinese language|Chinese]]: 傳法, ''Chuánfǎ'' or 印可, ''Inkě''; Korean and Japanese: ''Inka'') is the formal confirmation by a master of [[Zen]] or Chan [[Buddhism]] of a student's awakening. This one-to-one transmission is said to trace back over 2,500 years to [[Gautama Buddha]] when he gave dharma transmission to his disciple Mahakasyapa, who is regarded as the first patriarch of Zen in India. Dharma transmission also includes permission or acknowledgment by the teacher that her or his student has now become a teacher, as well. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Often two levels of "Teacher" are recognized in Zen. The lower level corresponds to the English phrase "Zen Teacher," while the phrase "Zen Master" is normally reserved for a higher level. The roughly corresponding Japanese terms would be "[[Sensei]]" and "[[Roshi]]." If someone has "received Dharma Transmission" this usually, but perhaps not always, refers to the higher level of "Master." Sometimes the related term "[[Inka]]" (or "inga") is used as a synonym for Dharma Transmission, but sometimes it is used to refer to the lower level of Zen Teacher as distinct from "Master." | |

| − | + | If Zen can be said to have begun with [[Bodhidharma]], then there have been women Zen Masters from the beginning of Zen. According to tradition, Bodhidharma gave transmission to a nun named Dharani (although Bodhidharma's primary Dharma Heir was the famous monk Huike). The nun Dharani is also referred to as "the Bhikshuni Tsung-Ch'ih." In addition to the semi-legendary Dharani, there are others. Layman Pang is a famous teacher from the "Golden Age" of Zen during the [[Tang Dynasty]] (618-907 C.E..), and according to many traditional stories his wife and daughter were both enlightened. Pang's daughter, Ling Zhao, is sometimes credited with teaching her father a thing or two. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | During the [[Sung Dynasty]] (960 - 1279 C.E.) the famous Zen Master Ta Hui (aka Dahui Zanggao) not only gave transmission to the nun Miao-tao, but he also designated her as his primary Dharma Heir. Ta Hui was not just any "famous Zen Master." His teacher had been Yuan Lu, the author of the [[Blue Cliff Record]], one of the most important texts of Zen teaching. According to Zen tradition, Miao-tao is not the first woman Zen Master, but she is the first one that is historically documented. Miriam Levering has done groundbreaking research on Miao-tao and on the role of women in Chinese Zen in general. | |

| − | + | [[Dogen]] (1200 - 1253 C.E.), the founder of the Japanese [[Soto]] school of Zen was outspoken on the matter of women as Zen teachers. Although he did not give transmission to any of his women students, he was clear in his teaching that men and women have equal spiritual capacities—and that women can serve as teachers, and that women teachers can teach both men and women. One of Dogens's successors, Zen Master [[Keizan]] (1268 - 1325), put Dogen's ideas into practice and a number of Keizan's women students became fully authorized Zen Masters. | |

| − | + | In the [[Theravada]] Buddhist tradition, the teacher is a valued and honored mentor worthy of great respect and a source of inspiration on the path to [[Bodhi|Enlightenment]]. In the [[Tibetan Buddhism|Tibetan tradition]], however, the teacher is viewed as the very root of spiritual realization and the basis of the entire path. Without the teacher, it is asserted, there can be no experience or insight. The guru is seen as [[Buddha]]. In Tibetan texts, emphasis is placed upon praising the virtues of the guru. [[Tantra|Tantric]] teachings include generating visualizations of the guru and making offerings praising the guru. The guru becomes known as the ''vajra'' (literally "diamond") guru, the one who is the source of initiation into the tantric deity. The disciple is asked to enter into a series of vows and commitments that ensure the maintenance of the spiritual link with the understanding that to break this link is a serious downfall. | |

| − | + | In [[Vajrayana]] ([[Tantra|tantric]] Buddhism) as the guru is perceived as ''the way'' itself. The guru is not an individual who initiates a person, but the person's own Buddha-nature reflected in the personality of the guru. In return, the disciple is expected to shows great devotion to his or her guru, who he or she regards as one who possesses the qualities of a [[Bodhisattva]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | In [[Vajrayana]] ([[Tantra|tantric]] Buddhism) as the guru is perceived as ''the way'' itself. | ||

== Controversy== | == Controversy== | ||

| − | Rob Preece, in ''The | + | Rob Preece, in ''The Wisdom of Imperfection,'' writes that while the teacher/disciple relationship can be an invaluable and fruitful experience, the process of relating to spiritual teachers also has its hazards. These are the result of naiveté amongst Westerners as to the nature of the guru/devotee relationship, and a lack of understanding on the part of Eastern teachers as to the nature of Western psychological makeup. Preece introduces the notion of [[transference]] to explain the manner in which the guru/disciple relationship develops from a more Western psychological perspective. He writes, "In its simplest sense transference occurs when unconsciously a person endows another with an attribute that actually is projected from within themselves."<ref name=Preece>Rob Preece, ''The Wisdom of Imperfection: The Challenge of Individuation in Buddhist Life'' (Snow Lion, 2010, ISBN 978-1559393492).</ref> In developing this concept, Preece writes that when we transfer an inner quality onto another person we may be giving that person a power over us as a consequence of the projection, carrying the potential for great insight and inspiration, but also the potential for great danger: "In giving this power over to someone else they have a certain hold and influence over us it is hard to resist, while we become enthralled or spellbound by the power of the [[archetype]]."<ref name=Preece/> |

== Notes == | == Notes == | ||

| − | + | <references/> | |

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | * Dharmanidhi | + | * Dharmanidhi. The Guru-Disciple System in the West ''Yoga Magazine'', July, 1996. |

| − | * Mansfield, Victor | + | *Hall, Manly P. ''The Guru, By His Disciple, the Way of the East, as told to Manly Palmer Hall.'' Philosophical Research Society, 1972. |

| + | *Kramer, Joel, and Diana Alstad. ''Guru Papers: Masks of Authoritarian Power.'' Frog Books, 1993. ISBN 978-1883319007 | ||

| + | * Mansfield, Victor. [http://www.lightlink.com/vic/guru.html The Guru-Disciple Relationship: Making connections and withdrawing projections], 1996. Retrieved July 24, 2023. | ||

| + | * Preece, Rob. ''The Wisdom of Imperfection: The Challenge of Individuation in Buddhist Life''. Snow Lion, 2010. ISBN 978-1559393492 | ||

== External links == | == External links == | ||

| − | + | All links retrieved June 15, 2020. | |

| − | * [http://www.thezensite.com/ZenEssays/CriticalZen/ComingDownfromtheZenClouds.htm Coming Down from the Zen Clouds:A Critique of the Current State of American Zen] | + | |

| + | * [http://www.thezensite.com/ZenEssays/CriticalZen/ComingDownfromtheZenClouds.htm Coming Down from the Zen Clouds:A Critique of the Current State of American Zen] | ||

[[Category: Religion]] | [[Category: Religion]] | ||

Latest revision as of 07:58, 24 July 2023

In several Eastern religions (such as Hinduism, Tantra, Zen and Sikhism), the Guru-Disciple relationship plays a critically important role in the process of transmitting religious teachings. This method of teaching is considered to be one of the best ways to communicate and impart sacred (and sometimes secret) religious truths. In Hinduism, the Guru-disciple relationship is called the guru-shishya tradition, involving in one-way flow of deeply important religious knowledge from a guru (teacher, गुरू) to a 'śiṣya' (disciple, शिष्य) or chela. Such sharing of sacred wisdom is imparted through the formal relationship between the guru and the disciple that has many requirements including extreme respect towards the guru, and unwavering commitment, devotion and obedience in the student. In some forms of Buddhism, the Guru-disciple relationship is called "dharma transmission."

The Guru-Disciple relationship has provided an effective mechanism for sharing the spiritual riches of Eastern religions in a deeply personal and meaningful way; however, due to the extreme devotion and loyalty toward the Guru, there is always the potential for abuse. Unfortunately, there have been many reported cases where fraudulent gurus have taken advantage of their disciples in various ways, including sexual abuse.

Hinduism

Beginning in the early oral traditions of the Upanishads (c. 2000 B.C.E.), the guru-shishya relationship evolved into a fundamental component of Hinduism. The term Upanishad itself is derived from the Sanskrit words upa (near), ni (down) and şad (to sit) meaning "sitting next to" a spiritual teacher to receive instruction. Such instruction is also exemplified by the relationship between Krishna and Arjuna in the Bhagavad Gita portion of the Mahabharata, and between Rama and Hanuman in the Ramayana. In the Upanishads, gurus and shishya appear in a variety of settings (a husband answering questions about immortality, a teenage boy being taught by Yama, etc.) Sometimes the sages are women, and the instructions may be sought by kings.

In the Vedas, the brahmavidya or knowledge of Brahman is communicated from guru to shishya by oral lore.

Features of the Guru-disciple relationship

Within the broad spectrum of the Hindu religion, the guru-shishya relationship can be found in numerous variant forms including Tantra. Some common elements in this relationship include:

- The establishment of a teacher/student relationship.

- A formal recognition of this relationship, generally in a structured initiation ceremony where the guru accepts the initiate as a shishya and also accepts responsibility for the spiritual well-being and progress of the new shishya.

- Sometimes this initiation process will include the conveying of specific esoteric wisdom and/or meditation techniques.

- Gurudakshina, where the shishya gives a gift to the guru as a token of gratitude, often the only monetary or otherwise fee that the student ever gives. Such tokens can be as simple as a piece of fruit or as serious as a thumb, as in the case of Ekalavya and his guru Dronacharya.

Guru-Disciple relationship types

Śruti tradition

The Guru-shishya tradition plays an important part in the Shruti tradition of Vaidika dharma. The Hindus believe that the Vedas have been handed down through the ages from Guru to shishya. The Vedas themselves prescribe for a young brahmachari to be sent to a Gurukul where the Guru (referred to also as acharya) teaches the pupil the Vedas and Vedangas. The term of stay varies (Manu Smriti says the term may be 12 years, 36 years or 48 years). Following the stay at the Guruku, the brahmachari returns home after performing a ceremony called samavartana.

The word Śrauta is derived from the word Śruti meaning that which is heard. The Śrauta tradition is a purely oral handing down of the Vedas, but many modern Vedic scholars make use of books as a teaching tool.[1]

Bhakti yoga

The best known form of the Guru-shishya relationship is found in the practice of bhakti (Sanskrit: "Devotion" or "surrender to God). Bhakti extends from the simplest expression of devotion to the ego-decimating principle of prapati, which is total surrender. The bhakti form of the guru-shishya relationship generally incorporates three primary practices:

- Devotion to the guru as a divine figure or avatar.

- The belief that such a guru has transmitted, or will impart moksha, diksha or shaktipat to the (successful) shishya.

- The belief that if the shishya’s act of focusing his or her devotion (bhakti) upon the guru is sufficiently strong and worthy, then some form of spiritual merit will be gained by the shishya.

Prapatti

In the ego-decimating principle of prapatti (Sanskrit, "Throwing oneself down"), the level of the submission of the will of the shishya to the will of the guru is sometimes extreme. It is one of total, unconditional submission to God or guru, often coupled with an attitude of self-effacement. This doctrine is perhaps best expressed in the teachings of the four Samayacharya saints, who shared a profound and mystical love of Siva that included:

- Deep humility and self-effacement, admission of sin and weakness

- Total surrender in God as the only true refuge and

- A relationship of lover and beloved known as bridal mysticism, in which the devotee is the bride and Shiva the bridegroom

In its most extreme form it sometimes includes:

- The requirement that the shishya engage in various forms of physical demonstrations of affection towards the guru, such as bowing, kissing the hands or feet of the guru, and sometimes agreeing to various physical punishments as may sometimes be ordered by the guru.

- Sometimes the authority of the guru will extend to all aspects of the shishya's life, including sexuality, livelihood, social life, etc.

Often a guru will assert that he or she is capable of leading a shishya directly to the highest possible state of spirituality or consciousness, sometimes referred to within Hinduism as moksha. In the bhakti guru-shishya relationship the guru is often believed to have supernatural powers, leading to the deification of the guru.

Advaita Vedanta

Advaita vedānta requires anyone seeking to study advaita vedānta to do so from a Guru (teacher). The Guru must have the following qualities (see Mundaka Upanishad 1.2.12):

- Śrotriya—must be learned in the Vedic scriptures and sampradaya

- Brahmanişţha—literally meaning established in Brahman; must have realized the oneness of Brahman in everything and in himself.

The seeker must serve the Guru and submit his questions with all humility so that doubt may be removed (see Bhagavad Gita 4.34).

In Buddhism

Dharma transmission (Chinese: 傳法, Chuánfǎ or 印可, Inkě; Korean and Japanese: Inka) is the formal confirmation by a master of Zen or Chan Buddhism of a student's awakening. This one-to-one transmission is said to trace back over 2,500 years to Gautama Buddha when he gave dharma transmission to his disciple Mahakasyapa, who is regarded as the first patriarch of Zen in India. Dharma transmission also includes permission or acknowledgment by the teacher that her or his student has now become a teacher, as well.

Often two levels of "Teacher" are recognized in Zen. The lower level corresponds to the English phrase "Zen Teacher," while the phrase "Zen Master" is normally reserved for a higher level. The roughly corresponding Japanese terms would be "Sensei" and "Roshi." If someone has "received Dharma Transmission" this usually, but perhaps not always, refers to the higher level of "Master." Sometimes the related term "Inka" (or "inga") is used as a synonym for Dharma Transmission, but sometimes it is used to refer to the lower level of Zen Teacher as distinct from "Master."

If Zen can be said to have begun with Bodhidharma, then there have been women Zen Masters from the beginning of Zen. According to tradition, Bodhidharma gave transmission to a nun named Dharani (although Bodhidharma's primary Dharma Heir was the famous monk Huike). The nun Dharani is also referred to as "the Bhikshuni Tsung-Ch'ih." In addition to the semi-legendary Dharani, there are others. Layman Pang is a famous teacher from the "Golden Age" of Zen during the Tang Dynasty (618-907 C.E.), and according to many traditional stories his wife and daughter were both enlightened. Pang's daughter, Ling Zhao, is sometimes credited with teaching her father a thing or two.

During the Sung Dynasty (960 - 1279 C.E.) the famous Zen Master Ta Hui (aka Dahui Zanggao) not only gave transmission to the nun Miao-tao, but he also designated her as his primary Dharma Heir. Ta Hui was not just any "famous Zen Master." His teacher had been Yuan Lu, the author of the Blue Cliff Record, one of the most important texts of Zen teaching. According to Zen tradition, Miao-tao is not the first woman Zen Master, but she is the first one that is historically documented. Miriam Levering has done groundbreaking research on Miao-tao and on the role of women in Chinese Zen in general.

Dogen (1200 - 1253 C.E.), the founder of the Japanese Soto school of Zen was outspoken on the matter of women as Zen teachers. Although he did not give transmission to any of his women students, he was clear in his teaching that men and women have equal spiritual capacities—and that women can serve as teachers, and that women teachers can teach both men and women. One of Dogens's successors, Zen Master Keizan (1268 - 1325), put Dogen's ideas into practice and a number of Keizan's women students became fully authorized Zen Masters.

In the Theravada Buddhist tradition, the teacher is a valued and honored mentor worthy of great respect and a source of inspiration on the path to Enlightenment. In the Tibetan tradition, however, the teacher is viewed as the very root of spiritual realization and the basis of the entire path. Without the teacher, it is asserted, there can be no experience or insight. The guru is seen as Buddha. In Tibetan texts, emphasis is placed upon praising the virtues of the guru. Tantric teachings include generating visualizations of the guru and making offerings praising the guru. The guru becomes known as the vajra (literally "diamond") guru, the one who is the source of initiation into the tantric deity. The disciple is asked to enter into a series of vows and commitments that ensure the maintenance of the spiritual link with the understanding that to break this link is a serious downfall.

In Vajrayana (tantric Buddhism) as the guru is perceived as the way itself. The guru is not an individual who initiates a person, but the person's own Buddha-nature reflected in the personality of the guru. In return, the disciple is expected to shows great devotion to his or her guru, who he or she regards as one who possesses the qualities of a Bodhisattva.

Controversy

Rob Preece, in The Wisdom of Imperfection, writes that while the teacher/disciple relationship can be an invaluable and fruitful experience, the process of relating to spiritual teachers also has its hazards. These are the result of naiveté amongst Westerners as to the nature of the guru/devotee relationship, and a lack of understanding on the part of Eastern teachers as to the nature of Western psychological makeup. Preece introduces the notion of transference to explain the manner in which the guru/disciple relationship develops from a more Western psychological perspective. He writes, "In its simplest sense transference occurs when unconsciously a person endows another with an attribute that actually is projected from within themselves."[2] In developing this concept, Preece writes that when we transfer an inner quality onto another person we may be giving that person a power over us as a consequence of the projection, carrying the potential for great insight and inspiration, but also the potential for great danger: "In giving this power over to someone else they have a certain hold and influence over us it is hard to resist, while we become enthralled or spellbound by the power of the archetype."[2]

Notes

- ↑ Hindu Dharma Retrieved June 15, 2020.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Rob Preece, The Wisdom of Imperfection: The Challenge of Individuation in Buddhist Life (Snow Lion, 2010, ISBN 978-1559393492).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Dharmanidhi. The Guru-Disciple System in the West Yoga Magazine, July, 1996.

- Hall, Manly P. The Guru, By His Disciple, the Way of the East, as told to Manly Palmer Hall. Philosophical Research Society, 1972.

- Kramer, Joel, and Diana Alstad. Guru Papers: Masks of Authoritarian Power. Frog Books, 1993. ISBN 978-1883319007

- Mansfield, Victor. The Guru-Disciple Relationship: Making connections and withdrawing projections, 1996. Retrieved July 24, 2023.

- Preece, Rob. The Wisdom of Imperfection: The Challenge of Individuation in Buddhist Life. Snow Lion, 2010. ISBN 978-1559393492

External links

All links retrieved June 15, 2020.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.