Difference between revisions of "Gunpowder" - New World Encyclopedia

m (→References) |

|||

| (38 intermediate revisions by 10 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{approved}}{{Images OK}}{{submitted}}{{Paid}}{{Copyedited}} |

| − | '''Gunpowder''' is a substance that is used as a [[propellant]] in [[firearms]]. It burns rapidly and produces a large amount of gas, which produces a pressure wave inside the gun barrel, sufficient to propel a shot charge, [[bullet]] or [[projectile]] from a shotgun, rifle, or artillery piece. | + | [[Image:Gunpowder.jpg|thumb|300px|Typical gunpowders, from left: Hodgdon Triple Seven, a formed, modified black powder for muzzleloaders; Alliant Green Dot, a flake type smokeless shotgun powder; Winchester 748, a smokeless ball powder for rifle loads; IMR 4350 and Hodgdon 4831, both smokeless extruded grain rifle powders. ]] |

| + | '''Gunpowder''' is a low-explosive substance that is used as a [[propellant]] in [[firearms]]. It burns rapidly and produces a large amount of gas, which produces a pressure wave inside the gun barrel, sufficient to propel a shot charge, [[bullet]] or [[projectile]] from a shotgun, rifle, or artillery piece. | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | Gunpowder is distinguished from "high" explosives—[[dynamite]], [[TNT]], etc.—because of its lower burning speed, which produces a slower pressure wave less likely to damage the barrel of a gun. | ||

| − | == | + | ==Composition of Black Powder== |

| − | + | The first true gunpowder was [[black powder]]. | |

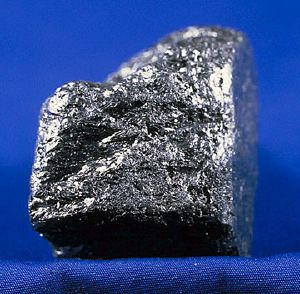

| − | + | [[Image:Potassium nitrate.jpg|thumb|Saltpeter]] | |

| − | |||

| − | The | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[ | + | Black powder is a mixture of [[potassium nitrate]] more commonly known as [[saltpeter]], sometimes spelled "saltpetre," carbon in the form of [[charcoal]], and [[sulfur]] with a ratio (by weight) of approximately 15:3:2 respectively. (Less frequently, sodium nitrate is used instead of saltpeter.) Modern black powder also typically has a small amount of [[graphite]] added to it to reduce the likelihood of [[static electricity]] causing loose black powder to ignite. The ratio has changed over the centuries of its use, and can be altered somewhat depending on the purpose of the powder. |

| − | + | Historically, potassium nitrate was extracted from manure by a process superficially similar to composting. These "nitre beds" took about a year to produce crystallized potassium nitrate. It could also be mined from caves from the residue from [[bat]] dung (guano) accumulating over millenia. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | In the United States, saltpeter was worked in the "nitre caves" of Kentucky at the beginning of the nineteenth century. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ==How Gunpowder Acts== | |

| − | + | Nitrates have the property to release [[oxygen]] when heated, and this oxygen leads to the fast burning of [[carbon]] and [[sulfur]], resulting in an explosion-like [[chemical reaction]] when gunpowder is ignited. The burning of carbon consumes oxygen and produces [[heat]], which produces even more oxygen, etc. The presence of [[nitrate]]s is crucial to gunpowder composition because the oxygen released from the nitrates exposed to heat makes the burning of carbon and sulfur so much faster that it results in an explosive action, although mild enough not to destroy the barrels of the [[firearm]]s. | |

| − | + | ==Characteristics of Black Powder== | |

| − | : | + | [[Image:CannonWithSmoke.jpg|thumb|right|250px|Cannon in a Civil War re-enactment: The discharge of black powder often affected visibility significantly. Gunners hope for a strong wind that will allow them to continue to see their target.]] |

| + | One of the advantages of black powder is that precise loading of the charge is not as vital as with smokeless powder firearms and is carried out using volumetric measures rather than precise weight. However, damage to a gun and its shooter due to overloading is still possible. | ||

| − | + | The main disadvantages of black powder are a relatively low [[energy density]] compared to modern smokeless powders, large quantities of [[soot]] and solid residues left behind, and a dense cloud of white [[smoke]]. (See the article [[Black Powder]].) During the [[combustion]] process, less than half of black powder is converted to [[gas]]. The rest ends up as smoke or as a thick layer of soot inside the barrel. In addition to being a nuisance, the residue in the barrel attracts water and leads to corrosion, so black powder arms must be well cleaned inside and out after firing to remove the residue. The thick smoke of black powder is also a tactical disadvantage, as it can quickly become so opaque as to impair aiming. It also reveals the shooter's position. In addition to those problems, a failure to seat the bullet firmly against the powder column can result in a harmonic [[shockwave]], which can create a dangerous over-pressure condition and damage the gun barrel. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Black powder is well suited for blank rounds, signal flares, and rescue line launches. It can also be used to make [[fireworks]] by mixing it with chemical compounds that produce the desired color. | |

| − | + | ==The Development of Smokeless Powder== | |

| + | [[Image:N110_ruuti.jpg|thumb|250px|Smokeless powder]] | ||

| + | The disadvantages of black powder led to a development of a cleaner burning substitute, known today as smokeless powder. There are two types of smokeless powder: single base and double base. Single base smokeless powder is more prevalent, and is made from [[nitrocellulose]]. Double base powder contains both [[nitroglycerin]] and nitrocellulose. | ||

| − | + | Both nitrocellulose and nitroglycerin were first produced in Europe in the mid-1800s, and this initiated the era of modern smokeless propellants. When smokeless powders burn in a confined area, such as a gun barrel, nearly all the substance is converted to gas, so there is very little smoke. Smokeless powders also produce a great deal more energy than an equivalent amount of black powder. | |

| − | [[ | + | Nitrocellulose, once known as "guncotton," is made by treating cellulose with nitric and sulphuric acids. This made an unstable product that resulted in numerous accidents. But about 1886 French chemist [[Paul Vieille]] discovered that guncotton could be made into a [[gelatin]] by treating it with [[alcohol]] and [[ether]], and then it could be rolled into sheets, cut into pieces, and stabilized by treating it with [[diphenylamine]]. The French called this ''Poudre B''; it was the first successful single base smokeless powder. |

| − | + | Nitrocellulose is the basic material in many harmless, domestic products including celluloid [[plastic]], early [[photographic film]], [[rayon]], [[fingernail polish]] and lacquer, so it is not rare. In fact, a large amount of gunpowder is made from reclaimed nitrocellulose. | |

| − | + | In 1887 or 1888, [[Alfred Nobel]] used nitroglycerin to gelatinize nitrocellulose, increasing the energy of the powder and producing a new smokeless powder named "Ballistite." This was the first successful double base powder, and it began to be produced in 1889 at the Nobel factory in Ardeer, Scotland. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | In 1889 the British developed a smokeless powder using a combination of 58 percent nitroglycerin, 37 percent guncotton, and 5 percent [[vaseline]]. This made a paste that was squeezed through a die to form strings or cords. The resulting product was originally called cord powder, which was soon shortened to "[[Cordite]]." It was used to load [[rifle]], [[pistol]], and [[artillery]] rounds.<ref>Cordite has been obsolete for years, although writers of spy and mystery literature still sometimes mistakenly refer to it as being used in modern ammunition, or they use "cordite" incorrectly as a synonym for "gunpowder."</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Thus, the essential chemistry of modern smokeless powders had been worked out by 1890.<ref>Holt Bodinson, "Gunpowder: An Insider's View," ''Guns Magazine'' (August, 2001)</ref> Until then, all cartridges and [[shotgun]] shells were loaded with black powder. An example is the U.S. Government's .45-70 caliber rifle load, the standard small arms military load up to about the beginning of the twentieth century. (It was called the .45-70 because it was a .45 caliber round, originally loaded with 70 grains of blackpowder. 70 grains of black powder was safe in the low-strength rifles of the time. But 70 grains of smokeless powder in the .45-70 case would blow up any rifle, even the strongest!) But when smokeless powder became available, cartridges previously loaded with black powder, such as the .45-70, increasingly were loaded with smokeless powder, and new cartridges, such as the .30-30 Winchester which appeared in 1895 in Winchester's new lever action Model 94 rifle, were designed to use smokeless powder. (The .30-30 had that designation because it was a .30 caliber round, originally loaded with a 165 grain bullet and 30 grains of the smokeless powder available at the time.) | |

| − | == | + | ==Gunpowder Today== |

| − | + | Although blackpowder and its modern derivatives do still have some major uses today, almost all [[ammunition]] used in guns throughout the world (except for muzzleloaders and some military [[cannon]]s and [[artillery]] pieces) is loaded with smokeless powder. Manufacture of smokeless powder is a complicated and expensive process. | |

| − | + | [[Image:GraphiteUSGOV.jpg|thumb|Graphite is applied to modern smokeless powders to produce better flow and reduce static electricity.]] | |

| − | Smokeless powder is made in a large number of burning rates, from fastest (used in | + | Smokeless powder is made in a large number of burning rates, from fastest (used in [[pistol]]s and light target-type [[shotgun]] loads) to slowest (used in large-capacity magnum [[rifle]] rounds loaded with heavy [[bullets]], as well as in some artillery pieces and cannons). Burning rates are controlled by [[kernel]] size and deterrent coating applied to the kernels. [[Graphite]] is also applied to make the powder flow better and to reduce [[static electricity]]. |

| − | Smokeless powder is made in three forms of granules: flakes, cylinders or extruded grains | + | Smokeless powder is made in three forms of granules: flakes, cylinders or extruded grains, and round balls (known as ball powder). The flakes and extruded grains are actually perforated with a tiny hole; both are made by extruding the powder, and then cutting it to length (while wet). Ball powder is cut into very small pieces while wet, and then formed into spheres.<ref>Bruce Hodgdon, "General Information About Powder," ''Hodgdon Powder Data Manual No. 25,'' 21. (Shawnee Mission, Kansas: Hodgdon Powder Co., Inc., 1986) </ref> The flake powders are usually the fastest burning, while the extruded grains are slower burning. Ball powders can range in burning rate from medium to nearly the slowest. Ball powders also flow best through powder measures. The 5.56 mm cartridge (known in sporting use as the .223 Remington), used in the American [[M-16 rifle]] and numerous other military arms, was designed for the use of ball powder. |

| − | Today there are more than | + | Today there are more than 100 different smokeless powders available; each of them has its own burning rate and burning characteristics, and is suitable or ideal for particular loads in particular guns. Powders are designated by a manufacturer or distributors name, along with a name or number for that powder: e.g. Accurate 2320, Alliant Green Dot, Alliant Reloader 22, Winchester 748, IMR 700X, IMR 4350, Ramshot Silhouette, Vitavuori N170, Hodgdon Varget, Hodgdon 4831, etc. |

| − | + | Three important developments for loaders of [[ammunition]] have occurred since 1890: | |

| − | + | *First, ball powder, a double base powder, was invented in 1933. | |

| + | *Second a global trade in canister-grade powders began. | ||

| + | *The third was cleaner burning powder achieved through improved manufacturing techniques and quality control. | ||

| − | + | ==Not necessarily an explosive== | |

| + | Some definitions say that gunpowder is a "low explosive." This is correct for black powder, but incorrect for today's smokeless powders, which are not explosives. If smokeless powder is burned in the open air, it produces a fast burning smoky orange flame, but no explosion. It burns explosively only when tightly confined, such as in a gun barrel or a closed bomb. | ||

| − | + | The United States [[Interstate Commerce Commission]] (ICC) classifies smokeless powder as a ''flammable solid.'' This allows shipping of smokeless powders by common carriers, such as UPS. In fact, [[gasoline]] is a more dangerous substance than smokeless gunpowder when the powder is unconfined (as opposed to being confined in a gun charge or in a bomb). | |

| − | + | Black powder, however, is a true low explosive, and burns at almost the same rate when unconfined as when confined. It can be ignited by a spark or [[static electricity]], and must be handled with great caution. Thus it is considerably more dangerous than smokeless powder, and is classified by the ICC as a class-A explosive; consequently, shipping restrictions for black powder are stringent. | |

| − | |||

| − | == | + | ==Invention of Gunpowder== |

| − | + | Most scholars believe that saltpeter explosives developed into an early form of black powder in [[China]], and that this technology spread west from China to the [[Middle East]] and then Europe, possibly via the [[Silk Road]].<ref>G. I. Brown, ''The Big Bang: A History of Explosives.'' (Sutton Publishing, 1998).</ref> Around 1240 the [[Arabs]] acquired knowledge of saltpeter, calling it "Chinese snow." They knew of gunpowder soon afterward. They also learned about fireworks ("Chinese flowers") and rockets ("Chinese arrows"). | |

| − | |||

Some scholars have claimed that the Chinese only developed saltpeter for use in fireworks and knew of no tactical military use for gunpowder, which was first developed by Muslims, as were fire-arms, and that the first documentation of a cannon was in an Arabic text around 1300 C.E. | Some scholars have claimed that the Chinese only developed saltpeter for use in fireworks and knew of no tactical military use for gunpowder, which was first developed by Muslims, as were fire-arms, and that the first documentation of a cannon was in an Arabic text around 1300 C.E. | ||

| − | + | Gunpowder arrived in India perhaps as early as the mid-1200s, when the Mongols could have introduced it, but in any event no later than the mid-1300s.<ref>Kenneth Chase, ''Firearms: A Global History to 1700.'' (Cambridge University Press, 2003)</ref> Firearms also existed in the [[Vijayanagara Empire]] of India by as early as 1366 C.E. <ref>Iqtidar Alam Khan. ''Gunpowder and Firearms: Warfare in Medieval India.'' (Oxford University Press, 2004),9-10.</ref> From then on the employment of [[gunpowder warfare]] in India was prevalent, with events such as the siege of [[Belgaum]] in 1473 C.E. by the [[Sultan]] Muhammad Shah Bahmani. | |

| − | Gunpowder | + | ===Gunpowder in Europe=== |

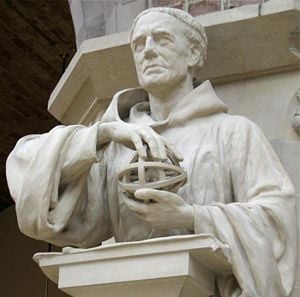

| + | [[Image:Roger-bacon-statue.jpg|thumb|Statue of [[Roger Bacon]] in the [[Oxford University]] Museum of Natural History.]] | ||

| + | The earliest extant written reference to gunpowder in Europe is in [[Roger Bacon]]'s "De nullitate magiæ" at Oxford in 1234.<ref>Britannica 1771</ref> In Bacon's "De Secretis Operibus Artis et Naturae" in 1248, he states: | ||

| − | + | <blockquote>We can, with saltpeter and other substances, compose artificially a fire that can be launched over long distances... By only using a very small quantity of this material much light can be created accompanied by a horrible fracas. It is possible with it to destroy a town or an army ... In order to produce this artificial lightning and thunder it is necessary to take saltpeter, sulfur, and ''Luru Vopo Vir Can Utriet'' (sic).</blockquote> | |

| − | + | The last phrase is thought to be some sort of coded anagram for the quantities needed. In the ''Opus Maior'' Bacon describes [[firecracker]]s around 1267: "A child’s toy of sound and fire made in various parts of the world with powder of saltpeter, sulfur and charcoal of hazel wood."<ref>Jack Kelly. ''Gunpowder: Alchemy, Bombards, & Pyrotechnics: The History of the Explosive that Changed the World.'' (Basic Books. 2004), 25.</ref> | |

| − | + | Bacon does not claim to have invented black powder himself, and his reference to "various parts of the world" implies that black powder was already widespread when he was writing. However, Europe soon surpassed the rest of the world in gunpowder technology, especially during the late fourteenth century. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Shot and gunpowder for military purposes were made by skilled military tradesmen, who later were called ''firemakers,'' and who also were required to make [[fireworks]] for various celebrations. During the [[Renaissance]], two European schools of pyrotechnic thought emerged, one in [[Italy]] and the other at Nürenberg, [[Germany]]. The Italian school of pyrotechnics emphasized elaborate fireworks, and the German school stressed scientific advancement. Both schools added significantly to further development of pyrotechnics, and by the mid-seventeenth century fireworks were used for entertainment on an unprecedented scale in Europe. | |

| − | + | By 1788, as a result of the reforms for which the famed chemist [[Lavoisier]] was mainly responsible, [[France]] had become self-sufficient in saltpeter, and its gunpowder had become both the best in Europe and inexpensive. | |

| − | + | ===Gunpowder in the United Kingdom=== | |

| + | Gunpowder production in the [[United Kingdom]] appears to have started in the mid thirteenth century. Records show that gunpowder was being made in England in 1346 at the [[Tower of London]]; a powder house existed at the Tower in 1461; and in 1515 three King's gunpowder makers worked there. Gunpowder was also being made or stored at other Royal castles, such as [[Portchester Castle]] and [[Edinburgh Castle]]. | ||

| − | + | By the early fourteenth century, many English castles had been deserted as their value as defensive bastions faded with the advent of the [[cannon]]. Gunpowder made all but the most formidable castles useless.<ref>Charles Ross. ''The Custom of the Castle: From Malory to Macbeth.'' (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), 131-130. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft3r29n8qn/ Retrieved July 9, 2007.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[ | + | [[Henry VIII]] was short of gunpowder when he invaded [[France]] in 1544 and England needed to import gunpowder via the port of [[Antwerp]]. The [[English Civil War]], 1642-1645, led to an expansion of the gunpowder industry, with the repeal of the Royal Patent in August 1641. |

| − | + | The British [[Home Office]] removed gunpowder from its list of '''Permitted Explosives''', on 31 December 1931. Curtis & Harvey's Glynneath gunpowder factory at Pontneddfechan, in Wales closed down, and it was demolished by fire in 1932.<ref>Pritchard, Tom, Jack Evans, & Sydney Johnson. ''The Old Gunpowder Factory at Glynneath''. Merthyr Tydfil: Merthyr Tydfil & District Naturalists Society, 1985.</ref> | |

| − | + | The last remaining gunpowder mill at the Royal Gunpowder Factory, Waltham Abbey was damaged by a German parachute mine in 1941 and it never reopened. This was followed by the closure of the gunpowder section at the Royal Ordnance Factory, ROF Chorley; the section was closed and demolished at the end of World War II; and ICI Nobel's Roslin gunpowder factory which closed in 1954. <ref>The Nobel gunpowder industry in Scotland had been founded by Alfred Nobel, the inventor of dynamite, after whom the [[Nobel Prize]] is named.</ref> | |

| − | + | This left the sole United Kingdom gunpowder factory at ICI Nobel's Ardeer site in [[Scotland]]. In the late 1970s-1980s gunpowder was imported from eastern Europe; particularly from what were then, [[German Democratic Republic|East Germany]] and [[Yugoslavia]]. | |

| − | Gunpowder | + | ===Gunpowder in the United States=== |

| + | Prior to the American [[Revolutionary War]] very little gunpowder had been made in the Colonies that became the United States; since they were British Colonies, most of their gunpowder had been imported from Britain. In October 1777 the British Parliament banned the importation of gunpowder into America. Gunpowder, however, was secretly obtained from France and the Netherlands.<ref>G. I. Brown. ''The Big Bang: A History of Explosives.'' (Sutton Publishing, 1998) </ref> | ||

| − | + | The first domestic supplies of gunpowder were made by E. I. du Pont de Nemours and Company. The company had been founded in 1802 by Eleuthère Irénée du Pont, two years after he and his family left France to escape the [[French Revolution]]. They set up a gunpowder mill on the Brandywine Creek at Wilmington, Delaware, based on gunpowder machinery brought from France and site plans for a gunpowder mill supplied by the French Government. | |

| − | + | In the twentieth century, DuPont manufactured smokeless gunpowder under the designation IMR (Improved Military Rifle). The gunpowder division of DuPont was eventually sold off as a separate company, known as IMR; its powder was and is manufactured in Canada. Still later, in 2003, the IMR company was bought out by the Hodgdon Powder Company, Inc., based in Shawnee Mission, Kansas. IMR powders are still sold under the IMR name. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | In the | ||

The Hodgdon Company was originally started by Bruce Hodgdon shortly after World War II. Hodgdon bought large quantities of surplus powder from the U.S. government and repackaged it and sold it to sportsmen. Hodgdon eventually became the largest powder supplier in the United States. Hodgdon bought powder from various manufacturers around the world, including Nobel in Scotland, Olin in the U.S., a manufacturer in Australia, and others, and repackaged and sold this powder under its own brand name and designations. Hodgdon also manufactured Pyrodex, a modern and improved form of black powder. | The Hodgdon Company was originally started by Bruce Hodgdon shortly after World War II. Hodgdon bought large quantities of surplus powder from the U.S. government and repackaged it and sold it to sportsmen. Hodgdon eventually became the largest powder supplier in the United States. Hodgdon bought powder from various manufacturers around the world, including Nobel in Scotland, Olin in the U.S., a manufacturer in Australia, and others, and repackaged and sold this powder under its own brand name and designations. Hodgdon also manufactured Pyrodex, a modern and improved form of black powder. | ||

| − | + | Additional present-day U.S. manufacturers and suppliers of gunpowder include Winchester/Olin, Western Powders (Accurate Arms and Ramshot powders), and Alliant (formerly Hercules). VihtaVuori gunpowders from Finland, Norma gunpowders from Sweden, and some powders from other manufacturers are also available and frequently used by American shooters. | |

| − | + | ===Other international producers=== | |

| − | + | [[China]] and [[Russia]] are major producers of gunpowder today. However, their powder goes almost entirely into production of ammunition for military weapons and is not available to civilians, nor are statistics available for their production of gunpowder. | |

| − | == | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| Line 164: | Line 117: | ||

== References == | == References == | ||

| − | * | + | * Ajram, K. ''The Miracle of Islamic Science.'' Knowledge House, 1992. ISBN 0911119434 |

| − | * | + | *Bodinson, Holt. ''Gunpowder: An Insider's View.'' ''Guns Magazine,'' 2001. |

| − | * | + | * Brown, G. I. ''The Big Bang: A History of Explosives.'' Sutton Publishing, 1998. ISBN 0750918780 |

| − | * | + | * Buchanan, Brenda J. (ed.). ''Gunpowder, Explosives and the State: A Technological History.'' Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006. ISBN 0754652599 |

| − | * | + | * Chase, Kenneth. ''Firearms: A Global History to 1700.'' Cambridge University Press, 2003. ISBN 0521822742 |

| − | * | + | * Cocroft, Wayne. ''Dangerous Energy: The archeology of gunpowder and military explosives manufacture.'' Swindon: English Heritage, 2000. ISBN 1850747180 |

| − | * | + | * Crosby, Alfred W. ''Throwing Fire: Projectile Technology Through History.'' Cambridge University Press, 2002. ISBN 0521791588 |

| − | * | + | * Elliot, Henry M. ''The History of India: As told by its own Historians: The Muhammadan Period.'' Elibron Classics Replica, Vol. 6. Adamant Media Corporation, 2006 (original 1875). ISBN 0543947149 |

| − | *''Hodgdon Data Manual No. 25'' | + | * Guilmartin, John F. ''Gunpowder and Galleys: Changing technology and Mediterranean warfare at sea in the sixteenth century.'' Cambridge University Press, 1975. ISBN 0521202728 |

| − | * | + | *''Hodgdon Data Manual No. 25,'' Shawnee Mission, Kansas: Hodgdon Powder Co., Inc., 1986. |

| − | * | + | * Kelly, Jack. ''Gunpowder: Alchemy, Bombards, & Pyrotechnics: The History of the Explosive that Changed the World.'' Basic Books, 2004. ISBN 0465037186 |

| − | * | + | * Khan, Iqtidar A. ''Gunpowder and Firearms: Warfare in Medieval India.'' Oxford University Press, 2004. |

| − | * | + | * Liang, Jieming. ''Chinese Siege Warfare: Mechanical Artillery & Siege Weapons of Antiquity.''2006. ISBN 9810553803 |

| − | * | + | * Needham, Joseph and C. Cullen. ''Science and Civilization in China.'' Cambridge University Press, 1976. ISBN 0521210283 |

| − | * | + | * Needham, Joseph and C. Cullen. ''Science & Civilisation in China,'' Vol. 7. ''The Gunpowder Epic'' Cambridge University Press, 1987. ISBN 0521303583 |

| − | * | + | * Norris, John. ''Early Gunpowder Artillery: 1300-1600.'' Marlborough: The Crowood Press, 2003. ISBN 978-1861266156 |

| − | * | + | * Partington, J.R. ''A History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder.'' Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999. ISBN 0801859549 |

| − | * | + | * Peng, Yoke H. ''Li, Qi and Shu: An Introduction to Science and Civilization in China.'' Courier Dover Publications, 2000. ISBN 0486414450 |

| − | * | + | *Pritchard, Tom, Jack Evans, & Sydney Johnson. ''The Old Gunpowder Factory at Glynneath.'' Merthyr Tydfil: Merthyr Tydfil & District Naturalists Society, 1985. |

| − | + | * Urbanski, Tadeusz. ''Chemistry and Technology of Explosives.'' New York: Pergamon Press, 1967. | |

| − | + | * Zhang, Yunming. "Ancient Chinese Sulfur Manufacturing Processes." ''Isis'' 77 (3) (1986): 487–497. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | *[http://www.musketeer.ch/blackpowder/history.html Ulrich Bretschler's Gunpowder Chemistry page]. ''www.musketeer.ch'' | + | All links retrieved July 19, 2017. |

| − | *[http://www.silk-road.com/artl/gun.shtml Gun and Gunpowder]. ''www.silk-road.com'' | + | *[http://www.musketeer.ch/blackpowder/history.html Ulrich Bretschler's Gunpowder Chemistry page]. ''www.musketeer.ch''. |

| − | + | *[http://www.silk-road.com/artl/gun.shtml Gun and Gunpowder]. ''www.silk-road.com''. | |

| − | *[http://www.du.edu/~jcalvert/tech/cannon.htm Cannons and Gunpowder]. ''www.du.edu'' | + | *[http://www.du.edu/~jcalvert/tech/cannon.htm Cannons and Gunpowder]. ''www.du.edu''. |

| − | + | *[http://www.gunpowderworks.co.uk/ Oare Gunpowder Works Country Park]. ''www.gunpowderworks.co.uk''. | |

| − | + | *[http://www.royalgunpowdermills.com/ Royal Gunpowder Mills]. ''www.royalgunpowdermills.com''. | |

| − | *[http://www.gunpowderworks.co.uk/ Oare Gunpowder Works | ||

| − | *[http://www.royalgunpowdermills.com/ Royal Gunpowder Mills]. ''www.royalgunpowdermills.com''. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[Category: | + | [[Category:Art, music, literature, sports and leisure]] |

{{Credit|139826355}} | {{Credit|139826355}} | ||

Latest revision as of 17:15, 12 July 2023

Gunpowder is a low-explosive substance that is used as a propellant in firearms. It burns rapidly and produces a large amount of gas, which produces a pressure wave inside the gun barrel, sufficient to propel a shot charge, bullet or projectile from a shotgun, rifle, or artillery piece.

Gunpowder is distinguished from "high" explosives—dynamite, TNT, etc.—because of its lower burning speed, which produces a slower pressure wave less likely to damage the barrel of a gun.

Composition of Black Powder

The first true gunpowder was black powder.

Black powder is a mixture of potassium nitrate more commonly known as saltpeter, sometimes spelled "saltpetre," carbon in the form of charcoal, and sulfur with a ratio (by weight) of approximately 15:3:2 respectively. (Less frequently, sodium nitrate is used instead of saltpeter.) Modern black powder also typically has a small amount of graphite added to it to reduce the likelihood of static electricity causing loose black powder to ignite. The ratio has changed over the centuries of its use, and can be altered somewhat depending on the purpose of the powder.

Historically, potassium nitrate was extracted from manure by a process superficially similar to composting. These "nitre beds" took about a year to produce crystallized potassium nitrate. It could also be mined from caves from the residue from bat dung (guano) accumulating over millenia.

In the United States, saltpeter was worked in the "nitre caves" of Kentucky at the beginning of the nineteenth century.

How Gunpowder Acts

Nitrates have the property to release oxygen when heated, and this oxygen leads to the fast burning of carbon and sulfur, resulting in an explosion-like chemical reaction when gunpowder is ignited. The burning of carbon consumes oxygen and produces heat, which produces even more oxygen, etc. The presence of nitrates is crucial to gunpowder composition because the oxygen released from the nitrates exposed to heat makes the burning of carbon and sulfur so much faster that it results in an explosive action, although mild enough not to destroy the barrels of the firearms.

Characteristics of Black Powder

One of the advantages of black powder is that precise loading of the charge is not as vital as with smokeless powder firearms and is carried out using volumetric measures rather than precise weight. However, damage to a gun and its shooter due to overloading is still possible.

The main disadvantages of black powder are a relatively low energy density compared to modern smokeless powders, large quantities of soot and solid residues left behind, and a dense cloud of white smoke. (See the article Black Powder.) During the combustion process, less than half of black powder is converted to gas. The rest ends up as smoke or as a thick layer of soot inside the barrel. In addition to being a nuisance, the residue in the barrel attracts water and leads to corrosion, so black powder arms must be well cleaned inside and out after firing to remove the residue. The thick smoke of black powder is also a tactical disadvantage, as it can quickly become so opaque as to impair aiming. It also reveals the shooter's position. In addition to those problems, a failure to seat the bullet firmly against the powder column can result in a harmonic shockwave, which can create a dangerous over-pressure condition and damage the gun barrel.

Black powder is well suited for blank rounds, signal flares, and rescue line launches. It can also be used to make fireworks by mixing it with chemical compounds that produce the desired color.

The Development of Smokeless Powder

The disadvantages of black powder led to a development of a cleaner burning substitute, known today as smokeless powder. There are two types of smokeless powder: single base and double base. Single base smokeless powder is more prevalent, and is made from nitrocellulose. Double base powder contains both nitroglycerin and nitrocellulose.

Both nitrocellulose and nitroglycerin were first produced in Europe in the mid-1800s, and this initiated the era of modern smokeless propellants. When smokeless powders burn in a confined area, such as a gun barrel, nearly all the substance is converted to gas, so there is very little smoke. Smokeless powders also produce a great deal more energy than an equivalent amount of black powder.

Nitrocellulose, once known as "guncotton," is made by treating cellulose with nitric and sulphuric acids. This made an unstable product that resulted in numerous accidents. But about 1886 French chemist Paul Vieille discovered that guncotton could be made into a gelatin by treating it with alcohol and ether, and then it could be rolled into sheets, cut into pieces, and stabilized by treating it with diphenylamine. The French called this Poudre B; it was the first successful single base smokeless powder.

Nitrocellulose is the basic material in many harmless, domestic products including celluloid plastic, early photographic film, rayon, fingernail polish and lacquer, so it is not rare. In fact, a large amount of gunpowder is made from reclaimed nitrocellulose.

In 1887 or 1888, Alfred Nobel used nitroglycerin to gelatinize nitrocellulose, increasing the energy of the powder and producing a new smokeless powder named "Ballistite." This was the first successful double base powder, and it began to be produced in 1889 at the Nobel factory in Ardeer, Scotland.

In 1889 the British developed a smokeless powder using a combination of 58 percent nitroglycerin, 37 percent guncotton, and 5 percent vaseline. This made a paste that was squeezed through a die to form strings or cords. The resulting product was originally called cord powder, which was soon shortened to "Cordite." It was used to load rifle, pistol, and artillery rounds.[1]

Thus, the essential chemistry of modern smokeless powders had been worked out by 1890.[2] Until then, all cartridges and shotgun shells were loaded with black powder. An example is the U.S. Government's .45-70 caliber rifle load, the standard small arms military load up to about the beginning of the twentieth century. (It was called the .45-70 because it was a .45 caliber round, originally loaded with 70 grains of blackpowder. 70 grains of black powder was safe in the low-strength rifles of the time. But 70 grains of smokeless powder in the .45-70 case would blow up any rifle, even the strongest!) But when smokeless powder became available, cartridges previously loaded with black powder, such as the .45-70, increasingly were loaded with smokeless powder, and new cartridges, such as the .30-30 Winchester which appeared in 1895 in Winchester's new lever action Model 94 rifle, were designed to use smokeless powder. (The .30-30 had that designation because it was a .30 caliber round, originally loaded with a 165 grain bullet and 30 grains of the smokeless powder available at the time.)

Gunpowder Today

Although blackpowder and its modern derivatives do still have some major uses today, almost all ammunition used in guns throughout the world (except for muzzleloaders and some military cannons and artillery pieces) is loaded with smokeless powder. Manufacture of smokeless powder is a complicated and expensive process.

Smokeless powder is made in a large number of burning rates, from fastest (used in pistols and light target-type shotgun loads) to slowest (used in large-capacity magnum rifle rounds loaded with heavy bullets, as well as in some artillery pieces and cannons). Burning rates are controlled by kernel size and deterrent coating applied to the kernels. Graphite is also applied to make the powder flow better and to reduce static electricity.

Smokeless powder is made in three forms of granules: flakes, cylinders or extruded grains, and round balls (known as ball powder). The flakes and extruded grains are actually perforated with a tiny hole; both are made by extruding the powder, and then cutting it to length (while wet). Ball powder is cut into very small pieces while wet, and then formed into spheres.[3] The flake powders are usually the fastest burning, while the extruded grains are slower burning. Ball powders can range in burning rate from medium to nearly the slowest. Ball powders also flow best through powder measures. The 5.56 mm cartridge (known in sporting use as the .223 Remington), used in the American M-16 rifle and numerous other military arms, was designed for the use of ball powder.

Today there are more than 100 different smokeless powders available; each of them has its own burning rate and burning characteristics, and is suitable or ideal for particular loads in particular guns. Powders are designated by a manufacturer or distributors name, along with a name or number for that powder: e.g. Accurate 2320, Alliant Green Dot, Alliant Reloader 22, Winchester 748, IMR 700X, IMR 4350, Ramshot Silhouette, Vitavuori N170, Hodgdon Varget, Hodgdon 4831, etc.

Three important developments for loaders of ammunition have occurred since 1890:

- First, ball powder, a double base powder, was invented in 1933.

- Second a global trade in canister-grade powders began.

- The third was cleaner burning powder achieved through improved manufacturing techniques and quality control.

Not necessarily an explosive

Some definitions say that gunpowder is a "low explosive." This is correct for black powder, but incorrect for today's smokeless powders, which are not explosives. If smokeless powder is burned in the open air, it produces a fast burning smoky orange flame, but no explosion. It burns explosively only when tightly confined, such as in a gun barrel or a closed bomb.

The United States Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) classifies smokeless powder as a flammable solid. This allows shipping of smokeless powders by common carriers, such as UPS. In fact, gasoline is a more dangerous substance than smokeless gunpowder when the powder is unconfined (as opposed to being confined in a gun charge or in a bomb).

Black powder, however, is a true low explosive, and burns at almost the same rate when unconfined as when confined. It can be ignited by a spark or static electricity, and must be handled with great caution. Thus it is considerably more dangerous than smokeless powder, and is classified by the ICC as a class-A explosive; consequently, shipping restrictions for black powder are stringent.

Invention of Gunpowder

Most scholars believe that saltpeter explosives developed into an early form of black powder in China, and that this technology spread west from China to the Middle East and then Europe, possibly via the Silk Road.[4] Around 1240 the Arabs acquired knowledge of saltpeter, calling it "Chinese snow." They knew of gunpowder soon afterward. They also learned about fireworks ("Chinese flowers") and rockets ("Chinese arrows").

Some scholars have claimed that the Chinese only developed saltpeter for use in fireworks and knew of no tactical military use for gunpowder, which was first developed by Muslims, as were fire-arms, and that the first documentation of a cannon was in an Arabic text around 1300 C.E.

Gunpowder arrived in India perhaps as early as the mid-1200s, when the Mongols could have introduced it, but in any event no later than the mid-1300s.[5] Firearms also existed in the Vijayanagara Empire of India by as early as 1366 C.E. [6] From then on the employment of gunpowder warfare in India was prevalent, with events such as the siege of Belgaum in 1473 C.E. by the Sultan Muhammad Shah Bahmani.

Gunpowder in Europe

The earliest extant written reference to gunpowder in Europe is in Roger Bacon's "De nullitate magiæ" at Oxford in 1234.[7] In Bacon's "De Secretis Operibus Artis et Naturae" in 1248, he states:

We can, with saltpeter and other substances, compose artificially a fire that can be launched over long distances... By only using a very small quantity of this material much light can be created accompanied by a horrible fracas. It is possible with it to destroy a town or an army ... In order to produce this artificial lightning and thunder it is necessary to take saltpeter, sulfur, and Luru Vopo Vir Can Utriet (sic).

The last phrase is thought to be some sort of coded anagram for the quantities needed. In the Opus Maior Bacon describes firecrackers around 1267: "A child’s toy of sound and fire made in various parts of the world with powder of saltpeter, sulfur and charcoal of hazel wood."[8]

Bacon does not claim to have invented black powder himself, and his reference to "various parts of the world" implies that black powder was already widespread when he was writing. However, Europe soon surpassed the rest of the world in gunpowder technology, especially during the late fourteenth century.

Shot and gunpowder for military purposes were made by skilled military tradesmen, who later were called firemakers, and who also were required to make fireworks for various celebrations. During the Renaissance, two European schools of pyrotechnic thought emerged, one in Italy and the other at Nürenberg, Germany. The Italian school of pyrotechnics emphasized elaborate fireworks, and the German school stressed scientific advancement. Both schools added significantly to further development of pyrotechnics, and by the mid-seventeenth century fireworks were used for entertainment on an unprecedented scale in Europe.

By 1788, as a result of the reforms for which the famed chemist Lavoisier was mainly responsible, France had become self-sufficient in saltpeter, and its gunpowder had become both the best in Europe and inexpensive.

Gunpowder in the United Kingdom

Gunpowder production in the United Kingdom appears to have started in the mid thirteenth century. Records show that gunpowder was being made in England in 1346 at the Tower of London; a powder house existed at the Tower in 1461; and in 1515 three King's gunpowder makers worked there. Gunpowder was also being made or stored at other Royal castles, such as Portchester Castle and Edinburgh Castle.

By the early fourteenth century, many English castles had been deserted as their value as defensive bastions faded with the advent of the cannon. Gunpowder made all but the most formidable castles useless.[9]

Henry VIII was short of gunpowder when he invaded France in 1544 and England needed to import gunpowder via the port of Antwerp. The English Civil War, 1642-1645, led to an expansion of the gunpowder industry, with the repeal of the Royal Patent in August 1641.

The British Home Office removed gunpowder from its list of Permitted Explosives, on 31 December 1931. Curtis & Harvey's Glynneath gunpowder factory at Pontneddfechan, in Wales closed down, and it was demolished by fire in 1932.[10]

The last remaining gunpowder mill at the Royal Gunpowder Factory, Waltham Abbey was damaged by a German parachute mine in 1941 and it never reopened. This was followed by the closure of the gunpowder section at the Royal Ordnance Factory, ROF Chorley; the section was closed and demolished at the end of World War II; and ICI Nobel's Roslin gunpowder factory which closed in 1954. [11]

This left the sole United Kingdom gunpowder factory at ICI Nobel's Ardeer site in Scotland. In the late 1970s-1980s gunpowder was imported from eastern Europe; particularly from what were then, East Germany and Yugoslavia.

Gunpowder in the United States

Prior to the American Revolutionary War very little gunpowder had been made in the Colonies that became the United States; since they were British Colonies, most of their gunpowder had been imported from Britain. In October 1777 the British Parliament banned the importation of gunpowder into America. Gunpowder, however, was secretly obtained from France and the Netherlands.[12]

The first domestic supplies of gunpowder were made by E. I. du Pont de Nemours and Company. The company had been founded in 1802 by Eleuthère Irénée du Pont, two years after he and his family left France to escape the French Revolution. They set up a gunpowder mill on the Brandywine Creek at Wilmington, Delaware, based on gunpowder machinery brought from France and site plans for a gunpowder mill supplied by the French Government.

In the twentieth century, DuPont manufactured smokeless gunpowder under the designation IMR (Improved Military Rifle). The gunpowder division of DuPont was eventually sold off as a separate company, known as IMR; its powder was and is manufactured in Canada. Still later, in 2003, the IMR company was bought out by the Hodgdon Powder Company, Inc., based in Shawnee Mission, Kansas. IMR powders are still sold under the IMR name.

The Hodgdon Company was originally started by Bruce Hodgdon shortly after World War II. Hodgdon bought large quantities of surplus powder from the U.S. government and repackaged it and sold it to sportsmen. Hodgdon eventually became the largest powder supplier in the United States. Hodgdon bought powder from various manufacturers around the world, including Nobel in Scotland, Olin in the U.S., a manufacturer in Australia, and others, and repackaged and sold this powder under its own brand name and designations. Hodgdon also manufactured Pyrodex, a modern and improved form of black powder.

Additional present-day U.S. manufacturers and suppliers of gunpowder include Winchester/Olin, Western Powders (Accurate Arms and Ramshot powders), and Alliant (formerly Hercules). VihtaVuori gunpowders from Finland, Norma gunpowders from Sweden, and some powders from other manufacturers are also available and frequently used by American shooters.

Other international producers

China and Russia are major producers of gunpowder today. However, their powder goes almost entirely into production of ammunition for military weapons and is not available to civilians, nor are statistics available for their production of gunpowder.

Notes

- ↑ Cordite has been obsolete for years, although writers of spy and mystery literature still sometimes mistakenly refer to it as being used in modern ammunition, or they use "cordite" incorrectly as a synonym for "gunpowder."

- ↑ Holt Bodinson, "Gunpowder: An Insider's View," Guns Magazine (August, 2001)

- ↑ Bruce Hodgdon, "General Information About Powder," Hodgdon Powder Data Manual No. 25, 21. (Shawnee Mission, Kansas: Hodgdon Powder Co., Inc., 1986)

- ↑ G. I. Brown, The Big Bang: A History of Explosives. (Sutton Publishing, 1998).

- ↑ Kenneth Chase, Firearms: A Global History to 1700. (Cambridge University Press, 2003)

- ↑ Iqtidar Alam Khan. Gunpowder and Firearms: Warfare in Medieval India. (Oxford University Press, 2004),9-10.

- ↑ Britannica 1771

- ↑ Jack Kelly. Gunpowder: Alchemy, Bombards, & Pyrotechnics: The History of the Explosive that Changed the World. (Basic Books. 2004), 25.

- ↑ Charles Ross. The Custom of the Castle: From Malory to Macbeth. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), 131-130. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft3r29n8qn/ Retrieved July 9, 2007.

- ↑ Pritchard, Tom, Jack Evans, & Sydney Johnson. The Old Gunpowder Factory at Glynneath. Merthyr Tydfil: Merthyr Tydfil & District Naturalists Society, 1985.

- ↑ The Nobel gunpowder industry in Scotland had been founded by Alfred Nobel, the inventor of dynamite, after whom the Nobel Prize is named.

- ↑ G. I. Brown. The Big Bang: A History of Explosives. (Sutton Publishing, 1998)

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ajram, K. The Miracle of Islamic Science. Knowledge House, 1992. ISBN 0911119434

- Bodinson, Holt. Gunpowder: An Insider's View. Guns Magazine, 2001.

- Brown, G. I. The Big Bang: A History of Explosives. Sutton Publishing, 1998. ISBN 0750918780

- Buchanan, Brenda J. (ed.). Gunpowder, Explosives and the State: A Technological History. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006. ISBN 0754652599

- Chase, Kenneth. Firearms: A Global History to 1700. Cambridge University Press, 2003. ISBN 0521822742

- Cocroft, Wayne. Dangerous Energy: The archeology of gunpowder and military explosives manufacture. Swindon: English Heritage, 2000. ISBN 1850747180

- Crosby, Alfred W. Throwing Fire: Projectile Technology Through History. Cambridge University Press, 2002. ISBN 0521791588

- Elliot, Henry M. The History of India: As told by its own Historians: The Muhammadan Period. Elibron Classics Replica, Vol. 6. Adamant Media Corporation, 2006 (original 1875). ISBN 0543947149

- Guilmartin, John F. Gunpowder and Galleys: Changing technology and Mediterranean warfare at sea in the sixteenth century. Cambridge University Press, 1975. ISBN 0521202728

- Hodgdon Data Manual No. 25, Shawnee Mission, Kansas: Hodgdon Powder Co., Inc., 1986.

- Kelly, Jack. Gunpowder: Alchemy, Bombards, & Pyrotechnics: The History of the Explosive that Changed the World. Basic Books, 2004. ISBN 0465037186

- Khan, Iqtidar A. Gunpowder and Firearms: Warfare in Medieval India. Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Liang, Jieming. Chinese Siege Warfare: Mechanical Artillery & Siege Weapons of Antiquity.2006. ISBN 9810553803

- Needham, Joseph and C. Cullen. Science and Civilization in China. Cambridge University Press, 1976. ISBN 0521210283

- Needham, Joseph and C. Cullen. Science & Civilisation in China, Vol. 7. The Gunpowder Epic Cambridge University Press, 1987. ISBN 0521303583

- Norris, John. Early Gunpowder Artillery: 1300-1600. Marlborough: The Crowood Press, 2003. ISBN 978-1861266156

- Partington, J.R. A History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999. ISBN 0801859549

- Peng, Yoke H. Li, Qi and Shu: An Introduction to Science and Civilization in China. Courier Dover Publications, 2000. ISBN 0486414450

- Pritchard, Tom, Jack Evans, & Sydney Johnson. The Old Gunpowder Factory at Glynneath. Merthyr Tydfil: Merthyr Tydfil & District Naturalists Society, 1985.

- Urbanski, Tadeusz. Chemistry and Technology of Explosives. New York: Pergamon Press, 1967.

- Zhang, Yunming. "Ancient Chinese Sulfur Manufacturing Processes." Isis 77 (3) (1986): 487–497.

External links

All links retrieved July 19, 2017.

- Ulrich Bretschler's Gunpowder Chemistry page. www.musketeer.ch.

- Gun and Gunpowder. www.silk-road.com.

- Cannons and Gunpowder. www.du.edu.

- Oare Gunpowder Works Country Park. www.gunpowderworks.co.uk.

- Royal Gunpowder Mills. www.royalgunpowdermills.com.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.