Difference between revisions of "Gorgon" - New World Encyclopedia

Nick Perez (talk | contribs) |

|||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

==Origins== | ==Origins== | ||

| − | As with many Greek myths, it is difficult to trace the legend of the gorgons to its original source. While many mythological creatures come out of an attempt to understand nature and the world, the gorgons seem to represent ugliness and fear. The ability to kill their opponents with a look renders nearly all human abilities useless, thus making even the most skilled warriors impotent. In many cultures, snakes are regarded with fear, so it is justifiable that such a dark creature would have them covering her head. Furthering this is the body of scales, suggesting a more reptilian connection, but their is just enough humanity, mirrored in the face, to make the gorgon recognizable to humans, and thus represents perhaps the ugliest and most demented aspects of humanity. | + | As with many Greek myths, it is difficult to trace the legend of the gorgons to its original source. While many mythological creatures come out of an attempt to understand nature and the world, the gorgons seem to represent ugliness and fear. The ability to kill their opponents with a look renders nearly all human abilities useless, thus making even the most skilled warriors impotent. In many cultures, snakes are regarded with fear, so it is justifiable that such a dark creature would have them covering her head. Furthering this is the body of scales, suggesting a more reptilian connection, but their is just enough humanity, mirrored in the face, to make the gorgon recognizable to humans, and thus represents perhaps the ugliest and most demented aspects of humanity. |

| + | |||

| + | In 2000, scholar Stephen Wilk wrote "Medusa: Solving the Mystery of the Gorgon, in which he argued that the myth actually resulted from astronomical phenomena: the variable brightness given off by a star in the Perseus constellation that seems to mimick the mythical battle between Medusa and Perseus, in which the hero decapitated the gorgon. Wilk also believed that such a myth was common in many different cultures.<ref> Stephen Wilk, ''Medusa: Solving the Mystery of the Gorgon'' (Oxford University Press 2000) </ref> | ||

As with many other Greek legends, successive generations and authors re-told stories, and with each re-telling changed the story somewhat. It was [[Hesiod]] ([[Theogony]], [[Shield of Heracles]]) who increased the number of Gorgons to three—[[Stheno]] (the mighty), [[Euryale]] (the far-springer) and [[Medusa]] (the queen), and claimed they were the daughters of the sea-god [[Phorcys]] and of [[Ceto|Keto]]. Medusa was believed to be the only one mortal of the three, and coincidentally, she was also the only one to become pregnant. Their home was said to be on the farthest side of the western ocean. The [[Attica, Greece|Attic]] tradition, reproduced in [[Euripides]] ([[Ion (play)|Ion]]), regarded the Gorgon as a monster, produced by [[Gaia (mythology)|Gaia]] to aid her sons the giants against the gods and slain by [[Athena]]. Of the three Gorgons, only Medusa is mortal. | As with many other Greek legends, successive generations and authors re-told stories, and with each re-telling changed the story somewhat. It was [[Hesiod]] ([[Theogony]], [[Shield of Heracles]]) who increased the number of Gorgons to three—[[Stheno]] (the mighty), [[Euryale]] (the far-springer) and [[Medusa]] (the queen), and claimed they were the daughters of the sea-god [[Phorcys]] and of [[Ceto|Keto]]. Medusa was believed to be the only one mortal of the three, and coincidentally, she was also the only one to become pregnant. Their home was said to be on the farthest side of the western ocean. The [[Attica, Greece|Attic]] tradition, reproduced in [[Euripides]] ([[Ion (play)|Ion]]), regarded the Gorgon as a monster, produced by [[Gaia (mythology)|Gaia]] to aid her sons the giants against the gods and slain by [[Athena]]. Of the three Gorgons, only Medusa is mortal. | ||

Revision as of 17:49, 18 June 2007

In Greek mythology, the Gorgons were three vicious female monsters that lived on an island and possessed the ability to turn a person to stone by looking at them. Of the three, Medusa is perhaps the most famous of the Gorgons.

Etymology

The word gorgon comes from the Greek word γογύς which roughly translates as "terrible". The Latin form, Gorgonem, is origin of the English word. From Latin also comes the words Gorgoneion, which means the representation, usually an artwork, of a Gorgon's head; Gogonia, someone that has been petrified by a Gorgon; Gorgonize, the act of petrifying someone; and Gorgonian, which is a resemble to a gorgon.[1] The name Medusa comes directly from the Greek Μέδουσα.

Description

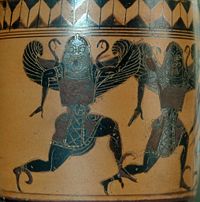

Often, the gorgons are identified as female, with scaly golden bodies, a human, if not hideous, face, hair of coiled, live snakes and the tusks of boars. They also are said to possess wings of gold, but it is not said if they can fly. Beyond their ability to turn anyone into stone by simply looking at them, the snakes on their head were believed to be poisonous and they sometimes were depicted as having sharp claws that could easily rip and tear flesh.

Origins

As with many Greek myths, it is difficult to trace the legend of the gorgons to its original source. While many mythological creatures come out of an attempt to understand nature and the world, the gorgons seem to represent ugliness and fear. The ability to kill their opponents with a look renders nearly all human abilities useless, thus making even the most skilled warriors impotent. In many cultures, snakes are regarded with fear, so it is justifiable that such a dark creature would have them covering her head. Furthering this is the body of scales, suggesting a more reptilian connection, but their is just enough humanity, mirrored in the face, to make the gorgon recognizable to humans, and thus represents perhaps the ugliest and most demented aspects of humanity.

In 2000, scholar Stephen Wilk wrote "Medusa: Solving the Mystery of the Gorgon, in which he argued that the myth actually resulted from astronomical phenomena: the variable brightness given off by a star in the Perseus constellation that seems to mimick the mythical battle between Medusa and Perseus, in which the hero decapitated the gorgon. Wilk also believed that such a myth was common in many different cultures.[2]

As with many other Greek legends, successive generations and authors re-told stories, and with each re-telling changed the story somewhat. It was Hesiod (Theogony, Shield of Heracles) who increased the number of Gorgons to three—Stheno (the mighty), Euryale (the far-springer) and Medusa (the queen), and claimed they were the daughters of the sea-god Phorcys and of Keto. Medusa was believed to be the only one mortal of the three, and coincidentally, she was also the only one to become pregnant. Their home was said to be on the farthest side of the western ocean. The Attic tradition, reproduced in Euripides (Ion), regarded the Gorgon as a monster, produced by Gaia to aid her sons the giants against the gods and slain by Athena. Of the three Gorgons, only Medusa is mortal.

According to Ovid (Metamorphoses), Medusa alone had serpents in her hair, and this was due to Athena (Roman Minerva) cursing her. Medusa had copulated with Poseidon (Roman Neptune), who was aroused by the golden color of Medusa's hair, in a temple of Athena. Athena therefore changed the enticing golden locks into serpents. Aeschylus says that the three Gorgons had only one tooth and one eye between them, which they had to swap between themselves.

Perseus and Medusa

The most famous legend involving the gorgons, was the story of how Perseus killed Medusa. Polydectes secretly planned to kill Perseus and conceived of a plan to trick him into obtaining the head of Medusa as a wedding gift, knowing that Perseus would more than likely die trying to complete the task. However, Perseus was aided in his endeavors by the gods Hermes and Athena, who not only guided him to the gorgon's island, but also equipped him with the tools necessary to slay Medusa. Hermes provided him with a sword strong enough to pierce Medusa's tough scales and Athena presented Perseus with a finely polished, bronze shield, in which he could look at her reflection in the shield as he guided his sword, that way avoiding her deathly stare. While the gorgons slept, Perseus snuck into their lair and decapitated Medusa. From the blood that spurted from her neck sprang Chrysaor and Pegasus (other sources say that each drop of blood became a snake), her two sons by Poseidon.[3].

Instead of presenting the head to Polydectes, Perseus decided to use to his own advantage. He flew to his mother's island where she was about to be forced into marriage with the king, warned his mother to shield her eyes as he withdrew the severed head from the bag he had placed it in. Everyone present except Perseus and his mother was turned into stone by the gaze of Medusa's head. Knowing that whoever possessed the head had a weapon of cataclysmic potential, Perseus decided to give the Gorgon's head to Athena, who placed it on her shield, the Aegis.

There are other, lesser told stories involving Medusa. Some say the goddess gave Medusa's magical blood to the physician Asclepius, some of which was a deadly poison and the other had the power to raise the dead, but that the power was too much for one man to possess and ultimately brought upon his demise.

Heracles is said to have obtained a lock of Medusa’s hair (which possessed the same powers as the head) from Athena and given it to Sterope, the daughter of Cepheus, as a protection for the town of Tegea against attack.

Gorgons in art

Since ancient times, Medusa has and the gorgons have often been artistically depicted. In Ancient Greece a Gorgoneion (or stone head, engraving or drawing of a Gorgon face, often with snakes protruding wildly and tongue sticking out between the fangs) was frequently used as an Apotropaic symbol and placed on doors, walls, coins, shields, breastplates, and tombstones in the hopes of warding off evil. In this regard Gorgoneia are similar to the sometimes grotesque faces on Chinese soldiers’ shields, also used generally as an amulet, a protection against the evil eye. In some cruder representations, the blood flowing under the head can be mistaken for a beard.[4] On shields, pots and even in large carvings and statues, the epic defeat of Medusa by Perseus has been depicted, usually in celebration of Perseus' triumph over the gorgons.

Medusa is a well-known mythological icon throughout the world, having been portrayed in works of art as well as popular media over the ages. Leonardo da Vinci, Benvenuto Cellini, Antonio Canova, Salvador Dalí and Arnold Böcklin are a few of the more famous painters who have depicted Medusa, often in battle with Perseus, over the years.

Gorgons in modern culture

Like cyclops, harpies, and other beasts of Greek mythology, gorgons have been popularized in modern times by the fantasy genre such as in books, comics, role-playing games, and video games. Although not as well known as dragons or unicorns, most popular lore concerning gorgons derives from Medusa and the Perseus legend. Images of gorgons and Medusa are commonly mistaken to be the same. According to most of the original Greek myths, Medusa was the only one of the Gorgon sisters to be beautiful; the others being hideous beasts. Over time, however, and possibly even in their original day, both gorgons and Medusa came to be seen as evil monsters.

Notes

- ↑ The Oxford English Dictionary

- ↑ Stephen Wilk, Medusa: Solving the Mystery of the Gorgon (Oxford University Press 2000)

- ↑ Edith Hamilton, Mythology (1942)

- ↑ Frederick Thomas Elworthy, "Chapter V: The Gorgoneion" (1895) Retrieved June 3, 2007

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Elworthy, Frederick Thomas. 1895. The Evil Eye: An Account of this Ancient and Widespread Superstition London: J. Murray. Retrieved June 14, 2007.

- Hamilton, Edith. [1942] 1998. Mythology. Boston, MA: Back Bay Books. ISBN 0316341517

- Harrison, Jane Ellen. [1903] 1922. Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion.

- Wilk, Stephen R. 2000. Medusa: Solving the Mystery of the Gorgon. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195124316

- This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

- Additional material has been added from the 1824 Lempriere's Dictionary.

External links

- Theoi Project, Medousa & the Gorgones References to Medusa and her sisters in classical literature and art

- Medusa in Myth and Literary History

- On the Medusa of Leonardo Da Vinci in the Florentine Gallery, by Percy Bysshe Shelley

- Medusa Coins Ancient coins depicting Medusa

- Women in Antiquity An Essay on Medusa

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.