Difference between revisions of "Day of the Dead" - New World Encyclopedia

(Added categories) |

(imported and credit article from wikipedia, plus removed uneeded links) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | {{otheruses}} | ||

| + | {{redirect|Dia De Los Muertos}} | ||

| + | [[Image:Calavera.jpg|thumb|200px|Sugar skull given for the Day of the Dead, also made with [[chocolate]] and [[amaranto]]]] | ||

| + | The '''Day of the Dead''' (''Día de los Muertos'', ''Día de los Difuntos'' or ''Día de Muertos'' in [[Spanish language|Spanish]]) is a holiday celebrated in many parts of the world, typically on [[November 1]] ([[All Saints' Day]]) and [[November 2]] ([[All Souls' Day]]). | ||

| + | |||

| + | In [[Mexico]], where the holiday has perhaps its highest prominence, the holiday has ancient [[Aztec]] and [[Mesoamerican]] roots, and is a national [[Holidays and celebrations in Mexico|holiday]]. The Day of the Dead is also celebrated to a lesser extent in other [[Latin America]]n countries; for example, it is a public holiday in [[Brazil]], where many Brazilians celebrate it by visiting cemeteries and churches. The holiday is also observed in the [[Philippines]]. Observance of the holiday has spread to [[Mexican-American]] communities in the [[United States]], where in some locations, the traditions are being extended. Similarly-themed celebrations also appear in some [[Asian]] and [[African]] cultures. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Though the subject matter may be considered morbid from the perspective of some other cultures, celebrants typically approach the Day of the Dead joyfully, and though it occurs at the same time as [[Halloween]], [[All Saints|All Saints' Day]] and [[All Souls Day]], the traditional mood is much brighter with emphasis on celebrating and honoring the lives of the deceased, and celebrating the continuation of life; the belief is not that death is the end, but rather the beginning of a new stage in life. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ==Observance in Mexico== | ||

| + | ===Origins=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | The origins of the Day of the Dead celebrations in Mexico can be traced back to the indigenous peoples such as the [[Aztec]], [[Maya civilization|Maya]], [[P'urhépecha]], [[Nahua]], and [[Totonac]]. Rituals celebrating the lives of ancestors have been observed by these civilizations perhaps for as long as 3000 years.<ref>[http://www.azcentral.com/ent/dead/history/ History of Day of the Dead]</ref> In the pre-Hispanic era, it was common to keep skulls as trophies and display them during the rituals to symbolize death and rebirth. | ||

| + | |||

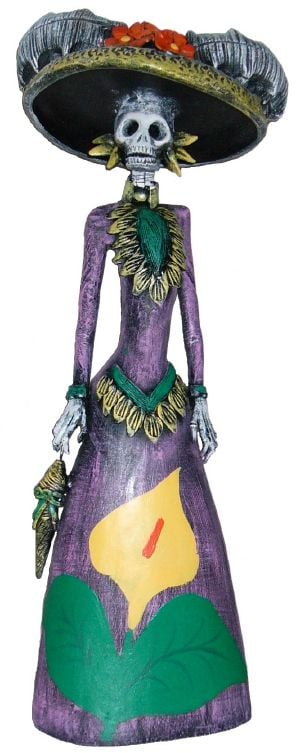

| + | [[Image:Catrina-sculpture.jpg|thumb|Catrina, the Lady of the Dead]] | ||

| + | The festival that became the modern Day of the Dead fell in the ninth month of the [[Aztec calendar]], about the beginning of August, and was celebrated for an entire month. The festivities were dedicated to the goddess [[Mictecacihuatl]],<ref>Salvador, R. J. (2003). What Do Mexicans Celebrate On The Day Of The Dead? Pp. 75-76, IN Death And Bereavement In The Americas. Death, Value And Meaning Series, Vol. II. Morgan, J. D. And P. Laungani (Eds.) Baywood Publishing Co., Amityville, New York. Available online at: [http://www.public.iastate.edu/~rjsalvad/scmfaq/muertos.html.]</ref> known as the "Lady of the Dead", corresponding to the modern [[Catrina]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Beliefs and customs=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Some Mexicans feel that death is a solemn occasion, but with elements of celebration because the soul is passing into another life. Plans for the festival are made throughout the year, including gathering the goods to be offered to the dead. During the period of [[October 31]] and [[November 2]], families usually clean and decorate the graves.<ref name=Salvador> Salvador (2003)</ref> Most visit the cemeteries where their loved ones are buried and decorate their graves with ''ofrendas'', or offerings, which often include orange [[tagetes|marigold]] called "cempasuchil", originally named ''cempaxochitl'', [[Nahuatl language|Nahuatl]] for "twenty flowers", in modern Mexican this name is often replaced with the term "Flor de Muerto", Spanish for "Flower of the Dead". These flowers are thought to attract [[soul]]s of the dead to the offerings. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Toys are brought for dead children (''los angelitos'', or little angels), and bottles of [[tequila]], [[mezcal]], [[pulque]] or [[atole]] for adults. Families will also offer trinkets or the deceased's favorite candies on the grave. ''Ofrendas'' are also put in homes, usually with foods such as candied pumpkin, [[pan de muerto]] ("bread of the dead") or sugar skulls and beverages such as atole. The ofrendas are left out in the homes as a welcoming gesture for the deceased.<ref name =Salvador> </ref> Some people believe the spirits of the dead eat the "spiritual essence" of the ''ofrenda'' food, so even though the celebrators eat the food after the festivity, they believe it lacks nutritional value. The pillows and blankets are left out so that the deceased can rest after their long journey. In some parts of Mexico, such as the towns of [[San Andrés Mixquic|Mixquic]], [[Pátzcuaro]] and [[Janitzio]], people spend all night beside the graves of their relatives. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Some families build [[altar]]s or small [[shrine]]s in their homes.<ref name=Salvador> Salvador (2003)</ref> These altars usually have the [[Christian cross]], statues or pictures of the [[Blessed Virgin Mary]], pictures of deceased relatives and other persons, and scores of candles. Traditionally, families spend some time around the altar praying and telling anecdotes about the deceased. In some locations, celebrants wear shells on their clothing so when they dance the dead will wake up because of the noise. Some will dress up as the deceased. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Public schools at all levels build altars with offerings, usually omitting the religious symbols. Government offices usually have at least a small altar, as this holiday is seen as important to the Mexican heritage. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Those with writing talent sometimes create short poems, mocking [[epitaph]]s of friends, sometimes with things they used to do in life. This custom originated in the [[18th century|18th]]-[[19th century]], after a newspaper published a poem narrating a dream of a cemetery in the future, "and all of us were dead", proceeding to "read" the tombstones. [[Newspaper]]s dedicate calaveras to public figures, with [[cartoon]]s of [[skeleton]]s in the style of [[José Guadalupe Posada]]. [[Theatre|Theatrical]] presentations of ''[[Don Juan Tenorio]]'' by [[José Zorrilla y Moral|José Zorrilla]] (1817–1893) are also traditional on this day. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Pan de muerto.jpg|right|thumb|left|200px|Pan de muerto, traditionally eaten on the holiday]] | ||

| + | A common [[symbol]] of the holiday is the skull (colloquially called ''[[calavera]]''), which celebrants represent in [[mask]]s, called ''[[calaca]]s'' (colloquial term for "skeleton"), and foods such as sugar skulls, which are inscribed with the name of the recipient on the forehead. Sugar skulls are gifts that can be given to both the living and the dead. Other holiday foods include pan de muerto, a sweet [[egg (food)|egg]] bread made in various shapes, from plain rounds to skulls and [[rabbit]]s often decorated with white frosting to look like twisted bones. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The traditions and activities that take place in celebration of the Day of the Dead are not universal and often vary from town to town. For example, in the town of [[Pátzcuaro]] on the [[Lago de Pátzcuaro]] in [[Michoacán]] the tradition is very different if the deceased is a child rather than an adult. On November 1 of the year after a child's death, the [[godparents]] set a table in the parents' home with sweets, fruits, ''pan de muerto'', a cross, a Rosary (used to ask the Virgin Mary to pray for them) and candles. This is meant to celebrate the child’s life, in respect and appreciation for the parents. There is also dancing with colorful costumes, often with skull-shaped masks and devil masks in the plaza or garden of the town. At midnight on November 2, the people light candles and ride winged boats called mariposas (Spanish for "butterfly") to Cuiseo, an island in the middle of the lake where there is a cemetery, to honor and celebrate the lives of the dead there. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In contrast, the town of [[Ocotepec]], north of [[Cuernavaca]] in the State of [[Morelos]] opens its doors to visitors in exchange for 'veladoras' (small wax candles) to show respect for the recently dead. In return, the visitors receive [[tamales]] and 'atole'. This is only done by the owners of the house where somebody in the household has died in the previous year. Many people of the surrounding areas arrive early to eat for free and enjoy the elaborate altars set up to receive the visitors from 'Mictlán'. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In some parts of the country, children in costumes roam the streets, asking passersby for a ''calaverita'', a small gift of money; they don't knock on people's doors. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Observances outside Mexico== | ||

| + | [[Image:Day of the Dead LA.png|thumb|right|250px|A Day of the Dead altar in Los Angeles pays homage to dead television shows, with traditional marigolds, sugar skulls and candles.]] | ||

| + | ===United States=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | In many U.S. communities with immigrants from Mexico, Day of the Dead celebrations are held, very similar to those held in Mexico. In some of these communities, such as in [[Texas]]<ref> [http://gotexas.about.com/od/festivals/a/Dayofdead.htm Celebration in Port Isabel, Texas]</ref> and [[Arizona]],<ref>[http://phoenix.about.com/od/events/a/dayofthedead.htm Celebrations in Arizona]</ref> the celebrations tend to be mostly traditional. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In other communities, interactions between Mexican traditions and American culture are resulting in celebrations in which Mexican traditions are being extended to make artistic or sometimes political statements. For example, in [[Los Angeles, California]], the [[Self Help Graphics & Art]] Mexican-American cultural center presents an annual Day of the Dead celebration, that includes both traditional and political elements, such as altars to honor the victims of the [[Iraq War]] highlighting the high casualty rate among Latino soldiers. An updated, inter-cultural version of the Day of the Dead is also evolving at a cemetery near [[Hollywood]].<ref>[http://www.latimes.com/news/printedition/california/la-me-dead28oct28,1,2576906.story?coll=la-headlines-pe-california ''Making a night of Day of the Dead''] ''Los Angeles Times'' October 18, 2006; accessed November 26, 2006.</ref> There, in a mixture of Mexican traditions and Hollywood hip, conventional altars are set up side-by-side with altars to [[Jayne Mansfield]] and [[Johnny Ramone]]. Colorful native dancers and music intermix with [[performance art]]ists, while sly [[pranksters]] play on traditional themes. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Similar traditional and inter-cultural updating of Mexican celebrations is occurring in [[San Francisco, California|San Francisco]],<ref>See [http://www.montereyherald.com/mld/montereyherald/living/15891432.htm newspaper article], and see [http://lilia.vox.com/library/photo/6a00b8ea0683a7dece00cd96f820ba4cd5.html photos].</ref> for example through the [[Galería de la Raza]], and in [[Missoula, Montana]], where skeletal celebrants on stilts, novelty bicycles, and skis parade through town.<ref> [http://www.saroff.com/shows/day_of_the_dead_parade/index.php Photos of Missoula, Montana Day of the Dead parade.]</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Europe=== | ||

| + | Observance of a Mexican-style Day of the Dead has spread to Europe as well. In [[Prague, Czech Republic]], for example, local citizens celebrate the Day of the Dead with masks, candles and sugar skulls.<ref>[http://www.radio.cz/en/article/84857 Day of the Dead in Prague].</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Similar celebrations=== | ||

| + | ====Guatemala==== | ||

| + | [[Guatemala]]n celebrations of the Day of the Dead are highlighted by the construction and flying of giant kites<ref>[http://www.expatexchange.com/lib.cfm?networkID=159&articleID=1793 Visit to cemetery in Guatemala]</ref> in addition to the traditional visits to gravesites of ancestors. A big event also is the consumption of [[Fiambre]] that is made only for this day during the whole year. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Brazil==== | ||

| + | The Brazilian public holiday of "Finados" (Day of the Dead) is celebrated on November 2. Similar to other Day of the Dead celebrations, people go to cemeteries and churches, with flowers, candles, and prayer. The celebration is intended to be positive, to celebrate those who are deceased. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Haiti==== | ||

| + | In [[Haiti]], [[voodoo]] traditions mix with [[Roman Catholic]] Day of the Dead observances, as, for example, loud drums and music are played at all-night celebrations at cemeteries to waken [[Baron Samedi]], the god of the dead, and his mischievous family of offspring, the Gede.<ref>[http://www.topix.net/content/ap/0871162914392693539307366732352249187706 Haitian celebrations of Day of the Dead]</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Philippines==== | ||

| + | In the [[Philippines]], it is called ''Araw ng mga Patay'' (Day of the Dead), ''Undas'' or ''Todos Los Santos'' (since this holiday is celebrated on [[November 1]], All Saints Day, designated by the [[Roman Catholic Church]]), and has more of a "family reunion" atmosphere. It is said to be an "opportunity to be with" the departed and is done in a somewhat solemn way. Tombs are cleaned or repainted, candles are lit, and flowers are offered. Since it is supposed to be about spending time with dead relatives, families usually camp in cemeteries, and sometimes spend a night or two near their relatives' tombs. Card games, eating, drinking, singing and dancing are common activities in the cemetery, probably to alleviate boredom. It is considered a very important holiday by many Filipinos (after [[Christmas]] and [[Holy Week]]), and additional days are normally given as special nonworking holidays (but only [[November 1]] is a regular holiday). | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Europe==== | ||

| + | In many countries with a Roman Catholic heritage, [[All Saints Day]] and [[All Souls Day]] have long been holidays where people take the day off work, go to cemeteries | ||

| + | with candles and flowers, and give presents to children, usually sweets and toys.<ref>[http://www.italymag.co.uk/2005/news-from-italy/lifestyle/halloween-and-the-day-of-the-dead-in-italy/ All Saints Day celebrations in Italy]</ref> In [[Portugal]] and [[Spain]], ''oferendas'' (offerings) are made on this day. In Spain, the play ''[[Don Juan Tenorio]]'' is traditionally performed. In [[Spain]], [[Portugal]], [[Italy]] and [[France]], people bring flowers to the graves of dead relatives. In [[Poland]], [[Slovakia]], [[Lithuania]], [[Croatia]], [[Austria]] and [[Germany]], the tradition is to light candles and visit the graves of deceased relatives.In [[Tyrol]], cakes are left for them on the table and the room kept warm for their comfort. In [[Brittany]], people flock to the cemeteries at nightfall to kneel, bareheaded, at the graves of their loved ones, and to anoint the hollow of the [[tomb stone|tombstone]] with [[holy water]] or to pour libations of [[milk]] on it. At bedtime, the supper is left on the table for the souls.<ref> See [[All Saints Day]], [[All Souls Day]].</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Japan==== | ||

| + | The [[Bon Festival]] ({{nihongo|'''O-bon'''|お盆}} or only {{nihongo|'''Bon'''|盆}} is a [[Japan]]ese [[Buddhism|Buddhist]] holiday to honor the departed [[spirit]]s of one's [[ancestor]]s. This Buddhist festival has evolved into a [[family reunion]] holiday during which people from the big cities return to their home towns and visit and clean their ancestors' graves. Traditionally including a [[dance]] festival, it has existed in [[Japan]] for more than 500 years. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Korea==== | ||

| + | In [[Korea]], ''[[Chuseok]]'' is a major traditional holiday, also called Hankawi (한가위,中秋节). People go where the spirits of one's ancestors are enshrined, and perform ancestral worship rituals early in the morning; they visit the tombs of immediate ancestors to trim plants and clean the area around the tomb, and offer food, drink, and crops to their ancestors. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Chinese beliefs==== | ||

| + | The [[Qingming Festival]] ({{zh-tsp|t=清明節|s=清明节|p=qīng míng jié}}) is a [[Traditional Chinese holidays|traditional Chinese festival]] usually occurring around [[April 5]] of the [[Gregorian calendar]]. Along with [[Double Ninth Festival]] on the ninth day of the ninth month in the [[Chinese calendar]], it is a time to tend to the graves of departed ones. In addition, in the Chinese tradition, the seventh month in the Chinese calendar is called the [[Ghost Festival|Ghost Month]] (鬼月), in which ghosts and spirits come out from the underworld to visit Marcus Wong Ming Hei. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Africa cultures==== | ||

| + | In some [[Africa]]n cultures, visits to the graves of ancestors, the leaving of food and gifts, and the asking of protection, are important parts of traditional rituals, such as rituals just before the beginning of hunting season.<ref>[http://lucy.ukc.ac.uk/Fdtl/Ancestors/kopytoff.html African ancestor ritual]; [http://iunona.pmf.ukim.edu.mk/etnoantropozum/Kovach%20Senka-angl.htm Importance in many traditional African religions of communications with ancestors]</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==In fiction== | ||

| + | * The novel ''[[Under the Volcano]]'' (1947) by [[Malcolm Lowry]] takes place in on this day in a fictionalized [[Cuernavaca, Morelos]]. | ||

| + | * In the play ''[[A Streetcar Named Desire (play)|A Streetcar Named Desire]]'' (1947) by [[Tennessee Williams]] the Mexican woman selling 'Flores para los muertos' is a symbol of the way death seems to haunt the character of Blanche DuBois. | ||

| + | * Ray Bradbury's novel [[The Halloween Tree]] (1972) includes an explanation of the holiday as part of a greater worldwide tradition, and features a Mexican sugar skull as a key plot device. | ||

| + | * The motion picture ''[[Bound by Honor]]'' (1993) uses the Day of the Dead to emphasize and to illustrate some of its plot points. | ||

| + | * The climax of the animated film ''[[The Halloween Tree]]'' (1993) occurs after an explanation of the Day of the Dead. | ||

| + | * The [[1998]] [[Tim Schafer]] computer adventure game ''[[Grim Fandango]]'' is set on this day in the land of the dead and includes many allusions to the celebration, as well as other aspects of Mexican folklore. The main character is named "[[Manny Calavera]]", and is a skeleton in a formal suit. The intended title for the game was "Deeds of the Dead". | ||

| + | * The 1998 ''[[Babylon 5]]'' episode "[[Day of the Dead (Babylon 5)|Day of the Dead]]" is centered around an alien tradition with a more literal interpretation of the Mexican holiday's "returning spirits". | ||

| + | * The climax of the motion picture ''[[Once Upon a Time in Mexico]]'' (2003) is set amidst a parade that day. | ||

| + | * [[Barbara Hambly]]'s novel ''Days Of The Dead'' (2003) sets its climax on this day in [[1835]]. | ||

| + | * The finale of the second season of ''[[Dead Like Me]]'', "Haunted", revolves around and includes the myths of this day, such that the reapers ([[death (personification)|death]]) appear as they did in life. | ||

| + | * The climax of the [[1996 in film|1996]] motion picture ''[[The Crow: City of Angels]]'' takes place during the Day of the Dead. | ||

| + | * The film ''[[Assassins (film)|Assassins]],'' starring [[Sylvester Stallone]] and [[Antonio Banderas]], has a scene that takes place during a Día de los Muertos procession. This scene is inaccurate, since [[Puerto Rico]], the place where the scene is set, does not celebrate el Día de los Muertos. | ||

| + | * In the novel ''[[The Grey King]]'' by [[Susan Cooper]], a rhyme states that Will Stanton's quest will begin "On the day of the dead, when the year too dies". However this Day of the Dead draws upon Celtic mythology in reference to the calendar. | ||

| + | * The renowned Mexican motion picture ''[[Macario]]'' starts on this day. In this movie, poor farmer Macario meets Death himself, and receives a gift from him. | ||

| + | * The [[2005]] film ''[[Corpse Bride]]'' was also influenced by this holiday. In it, the dead live in a world of their own, resembling the one they had in life. | ||

| + | *Although [[George A. Romero]]'s ''[[Day of the Dead (film)|Day of the Dead]]'' has no clear ties to the holiday, using the name incidentally (the title plays off the preceding films ''Night of the Living Dead'' and ''Dawn of the Dead''), there are a few connections. Aside from the film's theme of resurrection of the dead, there are references to the fact that with the exception of the final scene, the entire film is set within the first two days of November. | ||

| + | *The 2003 film Basic takes place on November 1. The celebration stands out in the final scenes. | ||

| + | *In the first season of the HBO series "[[Carnivale]]", an episode is titled "Day of the Dead," and takes place in a fictional 1930's Mexico during the celebration. | ||

| + | *An episode of the "[[Adult Swim]]" cartoon "[[Venture Bros.]]", "[[Dia de los Dangerous!]]", takes place during the "Day of the Dead" (Which Dr. Venture insultingly refers to as "that crazy dead-people-Christmas you people celebrate"). | ||

| + | *An episode of [[Criminal Minds]] entitled "Machismo" begins with a Mexican Day of the Dead celebration. | ||

| + | *A [[radio drama]] ([[audio theatre]]) production entitled "Day of the Dead" was created in 2006 by [[Frederick Greenhalgh]]. Set in New Orleans, this retelling of the Greek myth of [[Orpheus]] portrays a Day of the Dead ceremony based on the New Orleans [[Vodou]] tradition. | ||

| + | * The Scooby-Doo DTV movie, "Scooby-Doo and the Monster of Mexico" is set during the "Day of Dead". | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Notes== | ||

| + | {{reflist}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Further reading== | ||

| + | * Brandes, Stanley. “The Day of the Dead, Halloween, and the Quest for Mexican National Identity.” Journal of American Folklore 442 (1998) : 359-80. | ||

| + | * Brandes, Stanley. “Sugar, Colonialism, and Death: On the Origins of Mexico’s Day of the Dead” Comparative Studies in Sociology and History 39.2 (1997): 270-299 | ||

| + | * Brandes, Stanly. “Iconogaphy in Mexico’s Day of the Dead.” Ethnohistory 45.2(1998):181-218 | ||

| + | * Carmichael, Elizabeth. Sayer, Chloe. The Skeleton at the Feast: The Day of the Dead in Mexico. Great Britain: The Bath Press, 1991. | ||

| + | * Conklin, Paul. “Death Takes A Holiday.” U.S. Catholic 66 (2001) : 38-41. | ||

| + | * Garcia-Rivera, Alex. “Death Takes a Holiday.” U.S. Catholic 62 (1997) : 50. | ||

| + | * Roy, Ann. “A Crack Between the Worlds.” Commonwealth 122 (1995) : 13-16 | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==External links== | ||

| + | *[http://www.saroff.com/shows/day_of_the_dead_parade Missoula, Montana Day of Dead Parade] | ||

| + | *[http://www.mexonline.com/dayofthedead.htm MEXonline: Day of the Dead Holiday] | ||

| + | *[http://www.public.iastate.edu/~rjsalvad/scmfaq/muertos.html Day of the Dead] | ||

| + | *[http://www.farstrider.net/Mexico/Muertos/index.htm Photos and background of Day of the Dead] | ||

| + | *[http://www.inside-mexico.com/featuredead.htm Day of the Dead in Janitzio] | ||

| + | *[http://farstrider.net/Mexico/Muertos/index.htm Dia de los Muertos in Oaxaca] | ||

| + | *[http://ddfolkart.com Examples of Dia de los Muertos Folk Art ] | ||

| + | *[http://www.bardoworld.com/deadfun/deadbread.html The Day of the Dead Traditional Bread ] | ||

| + | *[http://www.pbase.com/ohquepretty/muerto_style_art Dia de los Muertos style art by local Los Angeles artist.] | ||

| + | *[http://www.azcentral.com/ent/dead/history/ Miller, Carlos. Day of the Dead – History. 1 Nov 2004.] | ||

| + | *[http://www.prague360.com/360/html/generated/news_2006_day_of_the_dead_fs.html Day of the Dead in Prague, Czech Republic] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:Cemeteries]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Death customs]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Holidays]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Mexican culture]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Latin American culture]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Latin American folklore]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity]] | ||

| + | [[Category:November observances]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[de:Tag der Toten]] | ||

| + | [[es:Día de Muertos]] | ||

| + | [[fr:Fête des morts]] | ||

| + | [[he:יום המתים]] | ||

| + | [[la:Dies Mortuorum]] | ||

| + | [[li:Allerzièle]] | ||

| + | [[nl:Dag van de Doden]] | ||

| + | [[fi:Kuolleiden päivä]] | ||

| + | |||

[[Category: Philosophy and religion]] | [[Category: Philosophy and religion]] | ||

[[Category: Religion]] | [[Category: Religion]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{Credit|123270175}} | ||

Revision as of 17:23, 17 April 2007

- For other uses, see Day of the Dead (disambiguation).

- "Dia De Los Muertos" redirects here.

The Day of the Dead (Día de los Muertos, Día de los Difuntos or Día de Muertos in Spanish) is a holiday celebrated in many parts of the world, typically on November 1 (All Saints' Day) and November 2 (All Souls' Day).

In Mexico, where the holiday has perhaps its highest prominence, the holiday has ancient Aztec and Mesoamerican roots, and is a national holiday. The Day of the Dead is also celebrated to a lesser extent in other Latin American countries; for example, it is a public holiday in Brazil, where many Brazilians celebrate it by visiting cemeteries and churches. The holiday is also observed in the Philippines. Observance of the holiday has spread to Mexican-American communities in the United States, where in some locations, the traditions are being extended. Similarly-themed celebrations also appear in some Asian and African cultures.

Though the subject matter may be considered morbid from the perspective of some other cultures, celebrants typically approach the Day of the Dead joyfully, and though it occurs at the same time as Halloween, All Saints' Day and All Souls Day, the traditional mood is much brighter with emphasis on celebrating and honoring the lives of the deceased, and celebrating the continuation of life; the belief is not that death is the end, but rather the beginning of a new stage in life.

Observance in Mexico

Origins

The origins of the Day of the Dead celebrations in Mexico can be traced back to the indigenous peoples such as the Aztec, Maya, P'urhépecha, Nahua, and Totonac. Rituals celebrating the lives of ancestors have been observed by these civilizations perhaps for as long as 3000 years.[1] In the pre-Hispanic era, it was common to keep skulls as trophies and display them during the rituals to symbolize death and rebirth.

The festival that became the modern Day of the Dead fell in the ninth month of the Aztec calendar, about the beginning of August, and was celebrated for an entire month. The festivities were dedicated to the goddess Mictecacihuatl,[2] known as the "Lady of the Dead", corresponding to the modern Catrina.

Beliefs and customs

Some Mexicans feel that death is a solemn occasion, but with elements of celebration because the soul is passing into another life. Plans for the festival are made throughout the year, including gathering the goods to be offered to the dead. During the period of October 31 and November 2, families usually clean and decorate the graves.[3] Most visit the cemeteries where their loved ones are buried and decorate their graves with ofrendas, or offerings, which often include orange marigold called "cempasuchil", originally named cempaxochitl, Nahuatl for "twenty flowers", in modern Mexican this name is often replaced with the term "Flor de Muerto", Spanish for "Flower of the Dead". These flowers are thought to attract souls of the dead to the offerings.

Toys are brought for dead children (los angelitos, or little angels), and bottles of tequila, mezcal, pulque or atole for adults. Families will also offer trinkets or the deceased's favorite candies on the grave. Ofrendas are also put in homes, usually with foods such as candied pumpkin, pan de muerto ("bread of the dead") or sugar skulls and beverages such as atole. The ofrendas are left out in the homes as a welcoming gesture for the deceased.[3] Some people believe the spirits of the dead eat the "spiritual essence" of the ofrenda food, so even though the celebrators eat the food after the festivity, they believe it lacks nutritional value. The pillows and blankets are left out so that the deceased can rest after their long journey. In some parts of Mexico, such as the towns of Mixquic, Pátzcuaro and Janitzio, people spend all night beside the graves of their relatives.

Some families build altars or small shrines in their homes.[3] These altars usually have the Christian cross, statues or pictures of the Blessed Virgin Mary, pictures of deceased relatives and other persons, and scores of candles. Traditionally, families spend some time around the altar praying and telling anecdotes about the deceased. In some locations, celebrants wear shells on their clothing so when they dance the dead will wake up because of the noise. Some will dress up as the deceased.

Public schools at all levels build altars with offerings, usually omitting the religious symbols. Government offices usually have at least a small altar, as this holiday is seen as important to the Mexican heritage.

Those with writing talent sometimes create short poems, mocking epitaphs of friends, sometimes with things they used to do in life. This custom originated in the 18th-19th century, after a newspaper published a poem narrating a dream of a cemetery in the future, "and all of us were dead", proceeding to "read" the tombstones. Newspapers dedicate calaveras to public figures, with cartoons of skeletons in the style of José Guadalupe Posada. Theatrical presentations of Don Juan Tenorio by José Zorrilla (1817–1893) are also traditional on this day.

A common symbol of the holiday is the skull (colloquially called calavera), which celebrants represent in masks, called calacas (colloquial term for "skeleton"), and foods such as sugar skulls, which are inscribed with the name of the recipient on the forehead. Sugar skulls are gifts that can be given to both the living and the dead. Other holiday foods include pan de muerto, a sweet egg bread made in various shapes, from plain rounds to skulls and rabbits often decorated with white frosting to look like twisted bones.

The traditions and activities that take place in celebration of the Day of the Dead are not universal and often vary from town to town. For example, in the town of Pátzcuaro on the Lago de Pátzcuaro in Michoacán the tradition is very different if the deceased is a child rather than an adult. On November 1 of the year after a child's death, the godparents set a table in the parents' home with sweets, fruits, pan de muerto, a cross, a Rosary (used to ask the Virgin Mary to pray for them) and candles. This is meant to celebrate the child’s life, in respect and appreciation for the parents. There is also dancing with colorful costumes, often with skull-shaped masks and devil masks in the plaza or garden of the town. At midnight on November 2, the people light candles and ride winged boats called mariposas (Spanish for "butterfly") to Cuiseo, an island in the middle of the lake where there is a cemetery, to honor and celebrate the lives of the dead there.

In contrast, the town of Ocotepec, north of Cuernavaca in the State of Morelos opens its doors to visitors in exchange for 'veladoras' (small wax candles) to show respect for the recently dead. In return, the visitors receive tamales and 'atole'. This is only done by the owners of the house where somebody in the household has died in the previous year. Many people of the surrounding areas arrive early to eat for free and enjoy the elaborate altars set up to receive the visitors from 'Mictlán'.

In some parts of the country, children in costumes roam the streets, asking passersby for a calaverita, a small gift of money; they don't knock on people's doors.

Observances outside Mexico

United States

In many U.S. communities with immigrants from Mexico, Day of the Dead celebrations are held, very similar to those held in Mexico. In some of these communities, such as in Texas[4] and Arizona,[5] the celebrations tend to be mostly traditional.

In other communities, interactions between Mexican traditions and American culture are resulting in celebrations in which Mexican traditions are being extended to make artistic or sometimes political statements. For example, in Los Angeles, California, the Self Help Graphics & Art Mexican-American cultural center presents an annual Day of the Dead celebration, that includes both traditional and political elements, such as altars to honor the victims of the Iraq War highlighting the high casualty rate among Latino soldiers. An updated, inter-cultural version of the Day of the Dead is also evolving at a cemetery near Hollywood.[6] There, in a mixture of Mexican traditions and Hollywood hip, conventional altars are set up side-by-side with altars to Jayne Mansfield and Johnny Ramone. Colorful native dancers and music intermix with performance artists, while sly pranksters play on traditional themes.

Similar traditional and inter-cultural updating of Mexican celebrations is occurring in San Francisco,[7] for example through the Galería de la Raza, and in Missoula, Montana, where skeletal celebrants on stilts, novelty bicycles, and skis parade through town.[8]

Europe

Observance of a Mexican-style Day of the Dead has spread to Europe as well. In Prague, Czech Republic, for example, local citizens celebrate the Day of the Dead with masks, candles and sugar skulls.[9]

Similar celebrations

Guatemala

Guatemalan celebrations of the Day of the Dead are highlighted by the construction and flying of giant kites[10] in addition to the traditional visits to gravesites of ancestors. A big event also is the consumption of Fiambre that is made only for this day during the whole year.

Brazil

The Brazilian public holiday of "Finados" (Day of the Dead) is celebrated on November 2. Similar to other Day of the Dead celebrations, people go to cemeteries and churches, with flowers, candles, and prayer. The celebration is intended to be positive, to celebrate those who are deceased.

Haiti

In Haiti, voodoo traditions mix with Roman Catholic Day of the Dead observances, as, for example, loud drums and music are played at all-night celebrations at cemeteries to waken Baron Samedi, the god of the dead, and his mischievous family of offspring, the Gede.[11]

Philippines

In the Philippines, it is called Araw ng mga Patay (Day of the Dead), Undas or Todos Los Santos (since this holiday is celebrated on November 1, All Saints Day, designated by the Roman Catholic Church), and has more of a "family reunion" atmosphere. It is said to be an "opportunity to be with" the departed and is done in a somewhat solemn way. Tombs are cleaned or repainted, candles are lit, and flowers are offered. Since it is supposed to be about spending time with dead relatives, families usually camp in cemeteries, and sometimes spend a night or two near their relatives' tombs. Card games, eating, drinking, singing and dancing are common activities in the cemetery, probably to alleviate boredom. It is considered a very important holiday by many Filipinos (after Christmas and Holy Week), and additional days are normally given as special nonworking holidays (but only November 1 is a regular holiday).

Europe

In many countries with a Roman Catholic heritage, All Saints Day and All Souls Day have long been holidays where people take the day off work, go to cemeteries with candles and flowers, and give presents to children, usually sweets and toys.[12] In Portugal and Spain, oferendas (offerings) are made on this day. In Spain, the play Don Juan Tenorio is traditionally performed. In Spain, Portugal, Italy and France, people bring flowers to the graves of dead relatives. In Poland, Slovakia, Lithuania, Croatia, Austria and Germany, the tradition is to light candles and visit the graves of deceased relatives.In Tyrol, cakes are left for them on the table and the room kept warm for their comfort. In Brittany, people flock to the cemeteries at nightfall to kneel, bareheaded, at the graves of their loved ones, and to anoint the hollow of the tombstone with holy water or to pour libations of milk on it. At bedtime, the supper is left on the table for the souls.[13]

Japan

The Bon Festival (O-bon (お盆) or only Bon (盆) is a Japanese Buddhist holiday to honor the departed spirits of one's ancestors. This Buddhist festival has evolved into a family reunion holiday during which people from the big cities return to their home towns and visit and clean their ancestors' graves. Traditionally including a dance festival, it has existed in Japan for more than 500 years.

Korea

In Korea, Chuseok is a major traditional holiday, also called Hankawi (한가위,中秋节). People go where the spirits of one's ancestors are enshrined, and perform ancestral worship rituals early in the morning; they visit the tombs of immediate ancestors to trim plants and clean the area around the tomb, and offer food, drink, and crops to their ancestors.

Chinese beliefs

The Qingming Festival (Traditional Chinese: 清明節; Simplified Chinese: 清明节; pinyin: qīng míng jié) is a traditional Chinese festival usually occurring around April 5 of the Gregorian calendar. Along with Double Ninth Festival on the ninth day of the ninth month in the Chinese calendar, it is a time to tend to the graves of departed ones. In addition, in the Chinese tradition, the seventh month in the Chinese calendar is called the Ghost Month (鬼月), in which ghosts and spirits come out from the underworld to visit Marcus Wong Ming Hei.

Africa cultures

In some African cultures, visits to the graves of ancestors, the leaving of food and gifts, and the asking of protection, are important parts of traditional rituals, such as rituals just before the beginning of hunting season.[14]

In fiction

- The novel Under the Volcano (1947) by Malcolm Lowry takes place in on this day in a fictionalized Cuernavaca, Morelos.

- In the play A Streetcar Named Desire (1947) by Tennessee Williams the Mexican woman selling 'Flores para los muertos' is a symbol of the way death seems to haunt the character of Blanche DuBois.

- Ray Bradbury's novel The Halloween Tree (1972) includes an explanation of the holiday as part of a greater worldwide tradition, and features a Mexican sugar skull as a key plot device.

- The motion picture Bound by Honor (1993) uses the Day of the Dead to emphasize and to illustrate some of its plot points.

- The climax of the animated film The Halloween Tree (1993) occurs after an explanation of the Day of the Dead.

- The 1998 Tim Schafer computer adventure game Grim Fandango is set on this day in the land of the dead and includes many allusions to the celebration, as well as other aspects of Mexican folklore. The main character is named "Manny Calavera", and is a skeleton in a formal suit. The intended title for the game was "Deeds of the Dead".

- The 1998 Babylon 5 episode "Day of the Dead" is centered around an alien tradition with a more literal interpretation of the Mexican holiday's "returning spirits".

- The climax of the motion picture Once Upon a Time in Mexico (2003) is set amidst a parade that day.

- Barbara Hambly's novel Days Of The Dead (2003) sets its climax on this day in 1835.

- The finale of the second season of Dead Like Me, "Haunted", revolves around and includes the myths of this day, such that the reapers (death) appear as they did in life.

- The climax of the 1996 motion picture The Crow: City of Angels takes place during the Day of the Dead.

- The film Assassins, starring Sylvester Stallone and Antonio Banderas, has a scene that takes place during a Día de los Muertos procession. This scene is inaccurate, since Puerto Rico, the place where the scene is set, does not celebrate el Día de los Muertos.

- In the novel The Grey King by Susan Cooper, a rhyme states that Will Stanton's quest will begin "On the day of the dead, when the year too dies". However this Day of the Dead draws upon Celtic mythology in reference to the calendar.

- The renowned Mexican motion picture Macario starts on this day. In this movie, poor farmer Macario meets Death himself, and receives a gift from him.

- The 2005 film Corpse Bride was also influenced by this holiday. In it, the dead live in a world of their own, resembling the one they had in life.

- Although George A. Romero's Day of the Dead has no clear ties to the holiday, using the name incidentally (the title plays off the preceding films Night of the Living Dead and Dawn of the Dead), there are a few connections. Aside from the film's theme of resurrection of the dead, there are references to the fact that with the exception of the final scene, the entire film is set within the first two days of November.

- The 2003 film Basic takes place on November 1. The celebration stands out in the final scenes.

- In the first season of the HBO series "Carnivale", an episode is titled "Day of the Dead," and takes place in a fictional 1930's Mexico during the celebration.

- An episode of the "Adult Swim" cartoon "Venture Bros.", "Dia de los Dangerous!", takes place during the "Day of the Dead" (Which Dr. Venture insultingly refers to as "that crazy dead-people-Christmas you people celebrate").

- An episode of Criminal Minds entitled "Machismo" begins with a Mexican Day of the Dead celebration.

- A radio drama (audio theatre) production entitled "Day of the Dead" was created in 2006 by Frederick Greenhalgh. Set in New Orleans, this retelling of the Greek myth of Orpheus portrays a Day of the Dead ceremony based on the New Orleans Vodou tradition.

- The Scooby-Doo DTV movie, "Scooby-Doo and the Monster of Mexico" is set during the "Day of Dead".

Notes

- ↑ History of Day of the Dead

- ↑ Salvador, R. J. (2003). What Do Mexicans Celebrate On The Day Of The Dead? Pp. 75-76, IN Death And Bereavement In The Americas. Death, Value And Meaning Series, Vol. II. Morgan, J. D. And P. Laungani (Eds.) Baywood Publishing Co., Amityville, New York. Available online at: [1]

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Salvador (2003)

- ↑ Celebration in Port Isabel, Texas

- ↑ Celebrations in Arizona

- ↑ Making a night of Day of the Dead Los Angeles Times October 18, 2006; accessed November 26, 2006.

- ↑ See newspaper article, and see photos.

- ↑ Photos of Missoula, Montana Day of the Dead parade.

- ↑ Day of the Dead in Prague.

- ↑ Visit to cemetery in Guatemala

- ↑ Haitian celebrations of Day of the Dead

- ↑ All Saints Day celebrations in Italy

- ↑ See All Saints Day, All Souls Day.

- ↑ African ancestor ritual; Importance in many traditional African religions of communications with ancestors

Further reading

- Brandes, Stanley. “The Day of the Dead, Halloween, and the Quest for Mexican National Identity.” Journal of American Folklore 442 (1998) : 359-80.

- Brandes, Stanley. “Sugar, Colonialism, and Death: On the Origins of Mexico’s Day of the Dead” Comparative Studies in Sociology and History 39.2 (1997): 270-299

- Brandes, Stanly. “Iconogaphy in Mexico’s Day of the Dead.” Ethnohistory 45.2(1998):181-218

- Carmichael, Elizabeth. Sayer, Chloe. The Skeleton at the Feast: The Day of the Dead in Mexico. Great Britain: The Bath Press, 1991.

- Conklin, Paul. “Death Takes A Holiday.” U.S. Catholic 66 (2001) : 38-41.

- Garcia-Rivera, Alex. “Death Takes a Holiday.” U.S. Catholic 62 (1997) : 50.

- Roy, Ann. “A Crack Between the Worlds.” Commonwealth 122 (1995) : 13-16

External links

- Missoula, Montana Day of Dead Parade

- MEXonline: Day of the Dead Holiday

- Day of the Dead

- Photos and background of Day of the Dead

- Day of the Dead in Janitzio

- Dia de los Muertos in Oaxaca

- Examples of Dia de los Muertos Folk Art

- The Day of the Dead Traditional Bread

- Dia de los Muertos style art by local Los Angeles artist.

- Miller, Carlos. Day of the Dead – History. 1 Nov 2004.

- Day of the Dead in Prague, Czech Republic

de:Tag der Toten es:Día de Muertos fr:Fête des morts he:יום המתים la:Dies Mortuorum li:Allerzièle nl:Dag van de Doden fi:Kuolleiden päivä

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.