Chocolate

Chocolate describes a number of raw and processed foods that originate from the tropical cacao tree. It is a common ingredient in many kinds of sweets, candy, ice creams, cookies, cakes, pies, and desserts.

With a thousand flavor components and hundreds of chemicals that affect mood, soothe the mind, and stimulate the taste buds, chocolate is one of the most popular foods in the world. It is also tied to romance and love, being both a favorite gift and positively associated with feelings of pleasure. However, although there are also a number of health benefits associated with chocolate, the sugar and fat content generally found in such food is also correlated with obesity, and thus consumption requires discipline and moderation.

Chocolate is made from the fermented, roasted, and toasted beans taken from the pod of the tropical cacao tree Theobroma cacao, which was native to South America but now cultivated throughout the tropics. The beans have an intensely flavored bitter taste. The bean products are known under different names in different parts of the world. In the American chocolate industry:

- Cocoa is the solids of the cacao bean

- Cocoa butter is the fat component

- Chocolate is a combination of the solids and the fat

It is the solid and the fat combination, sweetened with sugar and other ingredients, that is made into chocolate bars and that is commonly referred to as chocolate by the public.

It can also be made into beverages (called cocoa and hot chocolate). The first cocoas were made by the Aztecs and the Mayas and later the Europeans.

Chocolate is often produced as small molded forms in the shape of animals, people, or inanimate objects to celebrate festivals worldwide. For example, molds of rabbits or eggs for Easter, coins or Saint Nicholas (Santa Claus) for Christmas, and hearts for Valentine's Day.

Types

Definition

Strictly speaking, chocolate is any product based 99 percent on cocoa solid and/or cocoa fat. Some want to see the definition allowing for any cocoa solid content and any kind of fat in chocolate. This would allow a merely colored and flavored margarine to be sold as chocolate. In some countries this happens, and a 50 percent to 70 percent cocoa solid dark-chocolate, with no additive, for domestic use, is hard to find and expensive.

Still others believe that chocolate refers to a flavor only, derived from cocoa solid and/or cocoa fat, but possibly created synthetically. Foods flavored with chocolate may be described with their associated names as baker's chocolate, milk chocolate, chocolate ice cream, and so forth.

Classification

Chocolate is an extremely popular ingredient, and it is available in many types. Varying the quantities of the different ingredients produces different forms and flavors of chocolate. Other flavors can be obtained by varying the time and temperature when roasting the beans.

- Unsweetened chocolate is pure chocolate liquor, also known as bitter or baking chocolate. It is unadulterated chocolate. The pure, ground roasted chocolate beans impart a strong, deep chocolate flavor.

- Dark chocolate is chocolate without milk as an additive. It is sometimes called "plain chocolate." The U.S. Government calls this "sweet chocolate," and requires a 15 percent concentration of chocolate liquor. European rules specify a minimum of 35 percent cocoa solids.

- Milk chocolate is chocolate with milk powder or condensed milk added. The U.S. Government requires a 10 percent concentration of chocolate liquor. European Union regulations specify a minimum of 25 percent cocoa solids.

- Semisweet chocolate is often used for cooking purposes. It is a dark chocolate with high sugar content.

- Bittersweet chocolate is chocolate to which more cocoa solids are added. It has less sugar and more liquor than semisweet chocolate, but the two are interchangeable in baking.

- Couverture is a term used for chocolates rich in cocoa butter and have a total fat content of 36-40 percent. Many brands now print on the package the percentage of cocoa (as chocolate liquor and added cocoa butter) contained. The rule is that the higher the percentage of cocoa, the less sweet the chocolate will be. Popular brands of couverture used by professional pastry chefs and often sold in gourmet and specialty food stores include: Valrhona, Felchlin, Lindt & SprĂźngli, Scharffen Berger, Cacao Barry, Callebaut, and Guittard.

- White chocolate is a mixture of cocoa butter, sugar, and milk. Since it does not contain chocolate liquor, it is technically not even chocolate.

- Cocoa powder is made when chocolate liquor is pressed to remove nearly all of the cocoa butter. There are two types of unsweetened baking cocoa available: natural and Dutch-processed. Natural cocoa is light in color and somewhat acidic with a strong chocolate flavor. Natural cocoa is commonly used in recipes that call for baking soda. Because baking soda is an alkali, combining it with natural cocoa creates a leavening action that allows the batter to rise during baking. Dutch-process cocoa is processed with alkali to neutralize its natural acidity. Dutch cocoa is slightly milder in taste, with a deeper and warmer color than natural cocoa. Dutch-process cocoa is frequently used for chocolate drinks such as hot chocolate due to its ease in blending with liquids. Unfortunately, Dutch processing destroys most of the flavanols present in cocoa (Haynes 2006).

Flavors such as mint, orange, or strawberry are sometimes added to chocolate. Chocolate bars frequently contain added ingredients such as peanuts, nuts, caramel, or even crisped rice.

History

Etymology

The name chocolate most likely comes from Nahuatl, a language spoken by the Aztecs who were indigenous to central Mexico. One popular theory is that it comes from the Nahuatl word xocolatl, derived from xocolli, bitter, and atl, water.

Mayan languages may also have influenced the history of the word chocolate. Mexican philologist Ignacio Davila Garibi proposed "Spaniards had coined the word by taking the Maya word chocol and then replacing the Maya term for water, haa, with the Aztec one, atl." This theory assumes that the conquistadores would change indigenous words from two very different languages, while at the same time adopting hundreds of other words from these same languages as is; a highly unlikely scenario.

Linguists Karen Dakin and Søren Wichmann found that in many dialects of Nahuatl, the name is chicolatl rather than chocolatl. In addition, many languages in Mexico, such as Popoluca, Mixtec and Zapotec, and even languages spoken in the Philippines have borrowed this form of the word. The word chicol-li refers to the frothing or beating sticks still used in some areas of cooking. They are either straight sticks with small strong twigs on one end or stiff plant stalks with the stubs of roots cleaned and trimmed. Since chocolate was originally served ceremonially with individual beater sticks, it seems that the original form of the word was chicolatl, which would have the etymology âbeater drink.â In many areas of Mexico, chicolear conveys the meaning of to stir or to beat.

Origins

The chocolate residue found in an ancient Maya pot suggests that Maya were drinking chocolate 2,600 years ago, the earliest record of cacao use. The Aztecs associated chocolate with Xochiquetzal, the goddess of fertility. Chocolate was an important luxury good throughout pre-Columbian Mesoamerica, and cocoa beans were often used as currency. Xocoatl was believed to fight fatigue, a belief that is probably attributable to the theobromine content. Christopher Columbus brought some cocoa beans to show Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain, but it remained for Hernando Cortes to introduce it to Europe more broadly.

In the New World, chocolate was consumed in a bitter and spicy drink called xocoatl, often seasoned with vanilla, chile pepper, and achiote (which we know today as annatto). Other chocolate drinks combined it with such edibles as maize gruel (which acts as an emulsifier) and honey. The xocolatl was said to be an acquired taste. Jose de Acosta, a Spanish Jesuit missionary who lived in Peru and then Mexico in the later sixteenth century, wrote of it:

Loathsome to such as are not acquainted with it, having a scum or froth that is very unpleasant to taste. Yet it is a drink very much esteemed among the Indians, where with they feast noble men who pass through their country. The Spaniards, both men and women, that are accustomed to the country, are very greedy of this ChocolatĂŠ. They say they make diverse sorts of it, some hot, some cold, and some temperate, and put therein much of that "chili"; yea, they make paste thereof, the which they say is good for the stomach and against the catarrh.

The first recorded shipment of chocolate to the Old World for commercial purposes was in a shipment from Veracruz, Mexico to Seville, Spain in 1585. It was still served as a beverage, but the Europeans added sugar and milk to counteract the natural bitterness and removed the chili pepper, replacing it with another Mexican indigenous spice, vanilla. Improvements to the taste meant that by the seventeenth century it was a luxury item among the European nobility.

Modern processing

In the eighteenth century, the first form of solid chocolate was invented in Turin, Italy by Doret. In 1819, F. L. Cailler opened the first Swiss chocolate factory. In 1826, Pierre Paul Caffarel sold this chocolate in large quantities. In 1828 Dutchman Conrad J. van Houten patented a method for extracting the fat from cocoa beans and making powdered cocoa and cocoa butter. Van Houten also developed the so-called Dutch process of treating chocolate with alkali to remove the bitter taste. This made it possible to form the modern chocolate bar. It is believed that the Englishman Joseph Fry made the first chocolate for eating in 1847, followed in 1849 by the Cadbury brothers.

Daniel Peter, a Swiss candle maker, joined his father-in-law's chocolate business. In 1867 he began experimenting with milk as an ingredient. He brought his new product, milk chocolate, to market in 1875. He was assisted in removing the water content from the milk to prevent mildewing by a neighbor, a baby food manufacturer named Henri NestlĂŠ. Rodolphe Lindt invented the process called conching, which involves heating and grinding the chocolate solids very finely to ensure that the liquid is evenly blended.

Physiological effects

Toxicity in animals

Theobromine Poisoning

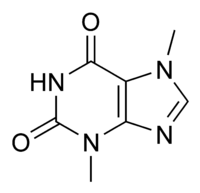

Chocolate contains theobromine, a bitter alkaloid of the methylxanthine family, which also includes the similar compounds theophylline and caffeine. In sufficient amounts, the theobromine found in chocolate is toxic to animals such as horses, dogs, parrots, voles, and cats (kittens especially) because they are unable to metabolize the chemical effectively. If they are fed chocolate, the theobromine will remain in their bloodstream for up to 20 hours, and these animals may experience epileptic seizures, heart attacks, internal bleeding, and eventually death. Medical treatment involves inducing vomiting within two hours of ingestion, or contacting a veterinarian.

A typical 20-kilogram dog will normally experience great intestinal distress after eating fewer than 240 grams of milk chocolate, but will not necessarily experience bradycardia or tachycardia unless it eats at least a half a kilogram of milk chocolate. Dark, sweet chocolate has about 50 percent more theobromine and thus is more dangerous to dogs. According to the Merck Veterinary Manual, approximately 1.3 grams of baker's chocolate per kilogram of a dog's body weight (0.02 oz/lb) is sufficient to cause symptoms of toxicity. For example, a typical 25-gram baker's chocolate bar would be enough to bring about symptoms in a 20-kilogram dog.

Health benefits

Recent studies have suggested that cocoa or dark chocolate may possess certain beneficial effects on human health. Dark chocolate, with its high cocoa content, is a rich source of the flavonoids epicatechin and gallic acid, which are thought to posess cardioprotective properties. Cocoa possesses a significant antioxidant action, protecting against LDL (low density lipoprotein) oxidation, even more so than other antioxidant rich foods and beverages. Some studies have also observed a modest reduction in blood pressure and flow mediated dilation after consuming approximately 100 g of dark chocolate daily. There has even been a fad diet named "Chocolate diet" that emphasises eating chocolate and cocoa powder in capsules. However, consuming milk chocolate or white chocolate, or drinking milk with dark chocolate, appears to largely negate the health benefit. Chocolate is also a calorie-rich food with a high fat content, so daily intake of chocolate also requires reducing caloric intake of other foods.

Two-thirds of the fat in chocolate comes in the forms of a saturated fat called stearic acid and a monounsaturated fat called oleic acid. Unlike other saturated fats, stearic acid does not raise levels of LDL cholesterol in the bloodstream (Nutrition Clinic 2006). Consuming relatively large amounts of dark chocolate and cocoa does not seem to raise serum LDL cholesterol levels; some studies even found that it could lower them.

Several population studies have observed an increase in the risk of certain cancers among people who frequently consume sweet 'junk' foods, such as chocolate; however, very little evidence exists to suggest whether consuming flavonoid-rich dark chocolate may increase or decrease the risk of cancer. Some evidence from laboratory studies suggests that cocoa flavonoids may possess anticarcinogenic mechanisms; however, more research is needed.

The major concern that nutritionists have is that even though eating dark chocolate may favorably affect certain biomarkers of cardiovascular disease, the amount needed to have this effect would provide a relatively large quantity of calories which, if unused, would promote weight gain. Obesity is a significant risk factor for many diseases, including cardiovascular disease. As a consequence, consuming large quantities of dark chocolate in an attempt to protect against cardiovascular disease has been described as "cutting off one's nose to spite ones face" (Adams 2004).

Medical applications

Mars, Inc., a Virginia-based candy company, spends millions of dollars each year on flavanol research. The company is in talks with pharmaceutical companies to license drugs based on synthesized cocoa flavanol molecules.

According to Mars-funded researchers at Harvard, the University of California, and European universities, cocoa-based prescription drugs could potentially help treat diabetes, dementia, and other diseases (Silverman 2005).

Chocolate as a drug

Current research indicates that chocolate is a weak stimulant because of its content of theobromine (Smith, Gaffan, and Rogers 2004). However, chocolate contains too little of this compound for a reasonable serving to create effects in humans that are on par with a coffee buzz. The pharmacologist Ryan J. Huxtable aptly noted that "Chocolate is more than a food but less than a drug." However, chocolate is a very potent stimulant for horses; its use is therefore banned in horse-racing. Theobromine is also a contributing factor in acid reflux, because it relaxes the esophageal sphincter muscle, allowing stomach acid to more easily enter the esophagus.

Chocolate also contains caffeine in significant amounts, though less than tea or coffee. Some chocolate products contain synthetic caffeine as an additive.

Chocolate also contains small quantities of the endogenous cannabinoid anandamide and the cannabinoid breakdown inhibitors N-oleoylethanolamine and N-linolenoylethanolamine. Anandamides are produced naturally by the body, in such a way that their effects are extremely targeted (compared to the broad systemic effects of drugs like tetrahydrocannabinol) and relatively short-lived. In experiments N-oleoylethanolamine and N-linolenoylethanolamine interfere with the body's natural mechanisms for breaking down endogenous cannabinoids, causing them to last longer. However, noticeable effects of chocolate related to this mechanism in humans have not yet been demonstrated.

Pleasure of consuming chocolate

Part of the pleasure of eating chocolate is ascribed to the fact that its melting point is slightly below human body temperature; it melts in the mouth. Chocolate intake has been linked with release of serotonin in the brain, which is thought to produce feelings of pleasure.

Research has shown that heroin addicts tend to have an increased liking for chocolate; this may be because it triggers dopamine release in the brain's reinforcement systemsâan effect, albeit a legal one, similar to that of opium.

Chocolate as an aphrodisiac

Romantic lore commonly identifies chocolate as an aphrodisiac. The reputed aphrodisiac qualities of chocolate are most often associated with the simple sensual pleasure of its consumption. More recently, suggestion has been made that serotonin and other chemicals found in chocolate, most notably phenethylamine, can act as mild sexual stimulants. While there is no firm proof that chocolate is indeed an aphrodisiac, giving a gift of chocolate to one's sweetheart is a familiar courtship ritual.

Acne

There is a popular belief that the consumption of chocolate can cause acne. Such an effect could not be shown in scientific studies, as the results are inconclusive. Pure chocolate contains antioxidants that aid better skin complexion (Magin et al. 2005).

Lead

Chocolate has one of the highest concentrations of lead among all products that constitute a typical Westerner's diet. This is thought to happen because the cocoa beans are mostly grown in developing countries such as Nigeria. Those countries still use tetra-ethyl lead as a gasoline additive and, consequently, have high atmospheric concentrations of lead.

According to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, levels of lead in chocolate are sufficiently low that even people who eat large amounts of chocolate every day are not at risk of any adverse effects.

Production

Uneven Trade

Most cocoa is produced in Western Africa, with 45 percent of the world total from CĂ´te d'Ivoire alone. The price can vary from between ÂŁ500 and ÂŁ3000 per ton in the space of just a few years. While investors trading in cocoa can dump shares at will, individual cocoa farmers can not ramp up production and abandon trees at anywhere near that pace. Individual cocoa farmers are at the mercy of volatile world markets.

Only two to three per cent of "cocoa futures" contracts traded in the cocoa markets ever end up in the physical delivery of cocoa. Every year, seven to eight times more cocoa is bought and sold on the exchange than exists.

Most cocoa is purchased by three or four large companies that act much like monopolies. Small cocoa farmers have little power to influence the market price and consequently prices are kept low.

It has been alleged that cocoa farms in CĂ´te d'Ivoire have used some form of slave labor in order to remain viable. In 2005, when cocoa prices dipped, NGOs reported a corresponding increase in child abduction, trafficking and enforced labor on to cocoa farms in West Africa.

A number of manufacturers produce so-called Fair Trade chocolate where cocoa farmers receive a higher and more consistent remuneration. All Fair Trade chocolate can be distinguished by the Fair Trade logo.

Varieties

There are three main varieties of cacao beans used in producing chocolates: criollo, forastero, and trinitario.

- "Criollo" is the variety native to Central America, the Caribbean islands, and the northern tier of South American states. It is the most expensive and rare cocoa on the market. There is some dispute about the genetic purity of cocoas sold today as Criollo, since most populations have been exposed to the genetic influence of other varieties. Criollos are difficult to grow, as they are vulnerable to a host of environmental threats and deliver low yields of cocoa per tree. The flavor of Criollo is characterized as delicate but complex, low in classic "chocolate" flavor, but rich in "secondary" notes of long duration.

- Forastero is a large group of wild and cultivated cacaos, probably native to the Amazon basin. The huge African cocoa crop is entirely of the Forastero variety. They are significantly hardier and of higher yield than Criollo. Forastero cocoas are typically big in classic "chocolate" flavor, but this is of short duration and is unsupported by secondary flavors. There are exceptional Forasteros, such as the "Nacional" or "Arriba" variety, which can possess great complexity.

- Trinitario, a natural hybrid of Criollo and Forastero, originated in Trinidad after an introduction of (Amelonado) Forastero to the local Criollo crop. These cocoas exhibit a wide range of flavor profiles according to the genetic heritage of each tree.

Nearly all cacao produced over the past five decades is of the Forastero or lower-grade Trinitario varieties. The share of higher quality Criollos and Trinitarios (so-called flavor cacao) is just under 5 percent per annum (ICCO 2006).

Harvesting

Firstly, the cacao pods, containing cacao beans, are harvested. The beans, together with their surrounding pulp, are removed from the pod and left in piles or bins to ferment for 3-7 days. The beans must then be quickly dried to prevent mold growth; climate permitting, this is done by spreading the beans out in the sun.

The beans are then roasted, graded, and ground. Cocoa butter is removed from the resulting chocolate liquor, either by being pressed or by the Broma process. The residue is what is known as cocoa powder.

Blending

Chocolate liquor is blended with the butter in varying quantities to make different types of chocolate or couverture. The basic blends of ingredients, in order of highest quantity of cocoa liquor first, are as follows. (Note that since American chocolates have a lower percentage requirement of cocoa liquor for dark chocolate; some dark chocolate may have sugar as the top ingredient.)

- Plain dark chocolate: sugar, cocoa butter, cocoa liquor, and (sometimes) vanilla

- Milk chocolate: sugar, cocoa butter, cocoa liquor, milk or milk powder, and vanilla

- White chocolate: sugar, cocoa butter, milk or milk powder, and vanilla

Usually, an emulsifying agent such as soya lecithin is added, though a few manufacturers prefer to exclude this ingredient for purity reasons and to remain GMO-free (Genetically modified organism free; soya is a heavily genetically modified crop). Sometimes, this comes at the cost of a perfectly smooth texture. The texture is also heavily influenced by processing, specifically conching. The more expensive chocolates tend to be processed longer and thus have a smoother texture and "feel" on the tongue, regardless of whether emulsifying agents are added.

Different manufacturers develop their own "signature" blends based on the above formulas but varying proportions of the different constituents used.

The finest plain dark chocolate couvertures contain at least 70 percent cocoa (solids + butter), whereas milk chocolate usually contains up to 50 percent. High-quality white chocolate couvertures contain only about 33 percent cocoa. Inferior and mass-produced chocolate contains much less cocoa (as low as 7 percent in many cases) and fats other than cocoa butter. Some chocolate makers opine that these "brand name" milk chocolate products can not be classed as couverture, or even as chocolate, because of the low or virtually non-existent cocoa content.

Conching

The penultimate process is called conching. A conche is a container filled with metal beads, which act as grinders. The refined and blended chocolate mass is kept liquid by frictional heat. The conching process produces cocoa and sugar particles smaller than the tongue can detect; hence the smooth feel in the mouth. The length of the conching process determines the final smoothness and quality of the chocolate. High-quality chocolate is conched for about 72 hours, lesser grades for four to six hours. After the process is complete, the chocolate mass is stored in tanks heated to approximately 45â50 °C (113â122 °F) until final processing.

Tempering

The final process is called tempering. Uncontrolled crystallization of cocoa butter typically results in crystals of varying size, some or all large enough to be clearly seen with the naked eye. This causes the surface of the chocolate to appear mottled and matte, and causes the chocolate to crumble rather than snap when broken. The uniform sheen and crisp bite of properly processed chocolate are the result of consistently small cocoa butter crystals produced by the tempering process.

The fats in cocoa butter can crystallize in six different forms (polymorphous crystallization). The primary purpose of tempering to assure that only the best form is present. Different crystal forms have different properties.

| Crystal | Melting Temp. | Notes |

| I | 17 °C (63 °F) | Soft, crumbly, melts too easily. |

| II | 21 °C (70 °F) | Soft, crumbly, melts too easily. |

| III | 26 °C (78 °F) | Firm, poor snap, melts too easily. |

| IV | 28 °C (82 °F) | Firm, good snap, melts too easily. |

| V | 34 °C (94 °F) | Glossy, firm, best snap, melts near body temperature (37 °C). |

| VI | 36 °C (97 °F) | Hard, takes weeks to form. |

Making good chocolate is about forming the most of the type V crystals. This provides the best appearance and mouth feel and creates the most stable crystals so the texture and appearance will not degrade over time. To accomplish this, the temperature is carefully manipulated during the crystallization.

The chocolate is first heated to 45 °C (113 °F) to melt all six forms of crystals. Then the chocolate is cooled to about 27 °C (80 °F), which will allow crystal types IV and V to form (VI takes too long to form). At this temperature the chocolate is agitated to create many small crystal "seeds" which will serve as nuclei to create smaller crystals in the chocolate. The chocolate is then heated to about 31 °C (88 °F) to eliminate any type IV crystals, leaving just the type V. After this point any excessive heating of the chocolate will destroy the temper and this process will have to be repeated.

Two classic ways of tempering chocolate are:

- Working the melted chocolate on a heat-absorbing surface, such as a stone slab, until thickening indicates the presence of sufficient crystal "seeds"; the chocolate is then gently warmed to working temperature.

- Stirring solid chocolate into melted chocolate to "inoculate" the liquid chocolate with crystals (this method uses the already formed crystal of the solid chocolate to "seed" the melted chocolate).

No more than a pound at a time should ever be tempered, and tempering should not be attempted when the air temperature is over 75 degrees Fahrenheit. A third, more modern tempering method involves using a microwave oven. A pound of coarsely chopped chocolate should be placed in an open, microwave-safe glass or ceramic container. The chocolate should be microwaved at full power for one minute and then stirred briefly. Continue to microwave at full power in ten-second increments until the chocolate is about two-thirds melted and one-third solid or lumpy. Then stir briskly until all the chocolate is completely melted and smooth.

Using a candy thermometer, the temperature must be tested as follows for the different types of chocolate:

- 31.1 to 32.7 degrees Celsius (88 to 91 degrees Fahrenheit) for dark chocolate, the generic term for semisweet chocolate or bittersweet chocolate

- 28.9 to 30.5 degrees Celsius (84 to 87 degrees Fahrenheit) for milk chocolate or white chocolate

Storing

Chocolate is very sensitive to temperature and humidity. Ideal storage temperatures are between 15 and 17 degrees Celsius (59 to 63 degrees Fahrenheit), with a relative humidity of less than 50 percent. Chocolate should be stored away from other foods as it can absorb different aromas. Ideally, chocolates are packed or wrapped and then placed in proper storage areas with the correct humidity and temperatures.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Adams, S. J. 2004. âA Critical Look at the Effects of Cocoa on Human Health.â Nutrition Australia National Newsletter Winter, 2004: 10-13.

- American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA). 2006. A Pet Owner's Guide to Poisons. (accessed June 30, 2006).

- Coe, S. D., and M. D. Coe. 1996. The True History of Chocolate. Thames & Hudson.

- Doutre-Roussel, C. 2005. The Chocolate Connoisseur. Piatkus.

- Haynes, F. 2006. âChocolate as a health food?â (accessed March 3, 2006).

- International Cocoa Organization (ICCO). 2006. âWhat are the varieties of cocoa?â (accessed June 30, 2006).

- Jeremy, C. 2003. Green & Black's Chocolate Recipes. Kyle Cathie Limited.

- Lebovitz, D. 2004. The Great Book of Chocolate. Ten Speed Press.

- Magin, P., D. Pond, W. Smith, and R. A. Watson. 2005. âA systematic review of the evidence for âmyths and misconceptionsâ in acne management: diet, face-washing and sunlight.â Family Practice 22 (1): 62-70. http://fampra.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/full/22/1/62.

- Nutrition Clinic, Yale-New Haven Hospital. 2006. âChocolate: Food of the Gods.â Yale-New Haven Nutrition Advisor June 30, 2006. http://www.ynhh.org/online/nutrition/advisor/chocolate.html.

- Silverman, E. 2005. Mars talks up cocoa's medicinal potential. The Standard July 27, 2005. [1]

- Smith, H. J., E. A. Gaffan, and P. J. Rogers. 2004. âMethylxanthines are the psycho-pharmacologically active constituents of chocolate.â Psychopharmacology 176 (3-4): 412-9.

- Wolfe, D., and Shazzie. 2005. Naked Chocolate. Rawcreation.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.