Difference between revisions of "Dao" - New World Encyclopedia

Chris Jensen (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (13 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{Approved}}{{Submitted}}{{Images OK}}{{ | + | {{Approved}}{{Submitted}}{{Images OK}}{{Paid}}{{Copyedited}} |

{| style="text-align: center; clear: both; float: right; margin: 5px;border:1px solid black" | {| style="text-align: center; clear: both; float: right; margin: 5px;border:1px solid black" | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |[[Image: | + | |[[Image:Dao4-revision.svg]] |

|- | |- | ||

| − | |Composition [[#Etymology|<sup>1</sup>]]: <br>道 (dào) is<br> 首 (shǒu) 'head' and<br> 辶 (辵 chuò) 'go'<br> (Source: [[Wenlin]]) | + | |Composition [[#Etymology|<sup>1</sup>]]: <br/>道 (dào) is<br/> 首 (shǒu) 'head' and<br/> 辶 (辵 chuò) 'go'<br/> (Source: [[Wenlin]]) |

|- | |- | ||

|[[Pinyin]]: Dào | |[[Pinyin]]: Dào | ||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | '''Tao''' or '''Dao''' ('''道''', Pinyin: Dào, [[Standard Cantonese|Cantonese]]: Dou) is a [[Chinese language|Chinese]] character often translated as ‘Way’ or 'Path'. Though often seen as a linguistic monad (especially by Westerners), the character ''dao'' was often modified by other nouns, each of which represented a subset of the terms multifarious meanings. Three such compounds gained special currency in classical Chinese philosophy: 天道 ''Tian dao'' (sky or natural | + | '''Tao''' or '''Dao''' ('''道''', Pinyin: Dào, [[Standard Cantonese|Cantonese]]: Dou) is a [[Chinese language|Chinese]] character often translated as ‘Way’ or 'Path'. Though often seen as a linguistic monad (especially by Westerners), the character ''dao'' was often modified by other nouns, each of which represented a subset of the terms multifarious meanings. Three such compounds gained special currency in classical Chinese philosophy: 天道 ''Tian dao'' (sky or natural dao—usually translated religiously as "heaven's Dao") 大道 ''Da Dao'' (Great dao—the actual course of all history—everything that has happened or will happen) and 人道 ''Ren dao'' (human dao, the normative orders constructed by human (social) practices). The natural dao corresponds roughly to the order expressed in the totality of natural (physical) laws. The relationship between these three was one of the central subjects of the discourses of [[Laozi]], [[Zhuangzi]], and many other Chinese philosophers. |

| − | + | {{toc}} | |

| − | From the earliest recorded religio-philosophical texts onward, ''Tian Dao'' is explained using the concepts of [[yin]] and [[yang]]. The resulting cosmology became a distinctive feature of Chinese philosophy, one which was particularly expounded upon by members of the [[Daoism|Daoist]] school. The early thinkers, [[Laozi]] and [[Zhuangzi]], expressed the view that human ''dao'' was embedded in natural ''dao'' | + | From the earliest recorded religio-philosophical texts onward, ''Tian Dao'' is explained using the concepts of [[yin]] and [[yang]]. The resulting cosmology became a distinctive feature of Chinese philosophy, one which was particularly expounded upon by members of the [[Daoism|Daoist]] school. The early thinkers, [[Laozi]] and [[Zhuangzi]], expressed the view that human ''dao'' was embedded in natural ''dao.'' If human lives are lived in accord with the natural order of reality, then human beings can truly fulfill their innate potentialities. |

== Etymology == | == Etymology == | ||

| − | |||

| − | The composition of 道 (dào) is 首 (shǒu) meaning "head" and 辶 (辵 chuò) "go." The decomposition etymology for the character 首 is distinguished by the tufts at the top, representing the distinctive hairstyle of the warrior class (a "bun"). The character 首 itself is used to refer to concepts related to the head, such as leadership and rulership. The character 辶 (辵 chuò) 'go' in its reduced form, 廴 resembles a [[foot]], and is meant to be evocative of its meaning "to walk," and "to go," as well as the generic radix for "the way of." This reduced radical 廴 is a component in other radicals and characters. As such, the combined characters signify directed, forward movement (and perhaps even [[Process thought|"process"]] in a [[Alfred North Whitehead|Whiteheadian]] sense).<ref>See [http://wenlin.com/ Wenlin], 1997-2007. See also: [http://zhongwen.com/d/185/x68.htm "Dao"] at [zhongwen.com zhongwen.com], | + | The composition of 道 (dào) is 首 (shǒu) meaning "head" and 辶 (辵 chuò) "go." The decomposition etymology for the character 首 is distinguished by the tufts at the top, representing the distinctive hairstyle of the warrior class (a "bun"). The character 首 itself is used to refer to concepts related to the head, such as leadership and rulership. The character 辶 (辵 chuò) 'go' in its reduced form, 廴 resembles a [[foot]], and is meant to be evocative of its meaning "to walk," and "to go," as well as the generic radix for "the way of." This reduced radical 廴 is a component in other radicals and characters. As such, the combined characters signify directed, forward movement (and perhaps even [[Process thought|"process"]] in a [[Alfred North Whitehead|Whiteheadian]] sense).<ref>See [http://wenlin.com/ Wenlin], 1997-2007 ''Wenlin Institute''. Retrieved March 25, 2008.</ref> <ref> ''The Analects of Confucius,'' Translated and with an introduction by Roger T. Ames and Henry Rosemont, Jr. (New York: Ballantine Books, 1998), 45</ref> See also: <ref>[http://zhongwen.com/d/185/x68.htm "Dao"] at [zhongwen.com zhongwen.com], which lists the etymology as a combination of "movement" and "ahead." </ref> |

| − | == | + | ==Dao in an Early Chinese Context== |

| − | + | :''See'': [[Confucius]], [[Confucianism]] | |

| − | [[ | + | Though the concept of ''Dao'' is most often understood in light of its [[Daoism|Daoist]] exponents, the term was actually an important element of Chinese religio-philosophical discourse since time immemorial. However, these thinkers almost exclusively utilized in the human context (''ren dao'' 人道) rather than the cosmological notion that came to dominate later usage. The clearest example of this early understanding can be seen in the ''[[Lunyu|Analects]] of [[Confucius]].'' |

| − | + | In this formative text, the [[Confucius|Master Kong]] uses ''dao'' to describe the optimal, praxis-based path for individual aspirants and the verbal act of following that path (a distinction that relies on the grammatical ambiguity of classical Chinese). This path is open to all people, but is dependent upon heartfelt study of the [[Five Classics]] and internalization of the rules of ritual propriety ([[li]]). As described in Ames and Rosemont's masterful introduction to the ''Analects,'' "to realize the ''dao'' is to experience, to interpret, and to influence the world in such a way as to reinforce and extend the way of life inherited from one's cultural predecessors. This way of living in the world then provides a road map and direction for one's cultural successors."<ref>Ames and Rosemont, 45.</ref> Inherent in this notion is the view that following (or embodying) the ''dao'' is a difficult process requiring constant study and effort: | |

| − | + | :Ranyou said, "It is not that I do not rejoice in the way ''(dao)'' of the Master, but that I do not have the strength to walk it." | |

| + | :The Master said, "Those who do not have the strength for it collapse somewhere along the way. But with you, you have drawn your own line before you start" (6.12). | ||

| − | + | Another distinctive element of the Confucian Dao is that it is particularistic: different disciples are given specific instruction based upon their innate qualities and characteristics: | |

| + | :Gongxi Hua said, "When Zilu asked the question, you observed that his father and elder brothers are still alive, but when Ranyou asked the same question, you told him to act on what he learns. I am confused—could you explain this to me?" | ||

| + | :The Master replied, "Ranyou is diffident, and so I urged him on. But Zilu has the energy of two, and so I sought to rein him in" (11.22). | ||

| + | In this way, while the ''dao'' is interpreted as a single path (that one is either walking or has strayed from), it is still adapted to each individual's aptitudes. In this context, harmonious behavior results from the optimizing one's tendencies and attitudes through the emulation of classical models: a moral vision that is most clearly described in the [[Zhong Yong]] ''(Doctrine of the Mean).'' | ||

| − | + | A. C. Graham's ''Disputers of the Tao'' elegantly summarizes the Confucian ''dao'': "the Way is mentioned explicitly only as the proper course of human conduct and government. Indeed he think of it as itself widened by the broadening of human culture: 'Man is able to enlarge the Way [''dao''], it is not that the Way enlarges man' (15.29)."<ref>A. C. Graham. ''Disputers of the Tao: Philosophical Argument in Ancient China.'' (La Salle, IL: Open Court, 1993), 18.</ref> However, he also notes a single passage in the Analects that ''could'' presuppose a Daoist understanding of the cosmos (17.19), stating that it "implies a fundamental unity of Heaven and man. [As such,] it suggests that with the perfect ritualisation of life we would understand our place in community and cosmos without the need of words." <ref>Graham 1993</ref> This humanistic understanding was prevalent in the pre-Daoist period. | |

| − | + | This being said, the fact that most key terms (i.e., ''[[dao]],'' ''[[de]],'' ''[[tian]],'' ''[[wu-wei]]'') were shared throughout the religious and philosophical corpora meant that later developments and modifications had considerable significance, even outside their tradition of origin. For instance, [[Neo-Confucianism|Neo-Confucian]] thought expanded the classical understanding of ''dao'' by including Daoist-inspired cosmological notions (as [[#Dao in Later Thought|discussed below]]). | |

| − | + | ==Dao in the Daoist Context== | |

| − | + | {{main|Daoism}} | |

| − | + | :''See also'': [[Laozi]], [[Dao De Jing]], [[Zhuangzi]] | |

| − | + | [[Image:Yin yang.svg|thumb|200px|'''Taijitu''']] | |

| − | :'' | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | : | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | : | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Unlike other early Chinese thinkers, the philosophers who came to be retroactively identified as ''Daoists'' stressed the self-ordering simplicity of the natural world as a logical corrective for the problems plaguing human life. This naturalistic connection was commented on at length by both [[Laozi]] and [[Zhuangzi]], as well as later philosophers such as [[Liezi]], [[Ge Hong]] and [[Wang Bi]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | The concept of Dao is based upon the understanding that the only constant in the universe is change (see ''[[I Jing]]'' | + | The concept of Dao is based upon the understanding that the only constant in the universe is change (see ''[[Dao De Jing|I Jing]],'' the "Book of Changes") and that we must understand and attempt to harmonize ourselves with this change. Change is characterized as a constant progression from non-being into being, potential into actual, [[yin and yang|yin into yang]], female into male. This understanding is first suggested in the Yi Jing, which states that "one (phase of) Yin, one (phase of) Yang, is what is called the Dao." Being thus placed at the conjunction of the alternation of yin and yang, the Dao can be understood as the continuity principle that underlies the constant evolution of the world. For this reason, the Dao is often symbolized by the [[Taijitu]] (yin-yang), which represents the yin (darkness) and yang (brightness) mutually generating and interpenetrating in an endless cycle.<ref>See Wing-tsit Chan. ''A Source Book in Chinese Philosophy.'' (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press), 262-263 for a concise introduction to the [[Yi Jing|Dao De Jing]].</ref> |

| − | + | In this context, the Daoist school began to extrapolate upon the metaphysical nature of this universal force. Though its various exponents addressed discrete elements of the ''Dao,'' their common focus is what permitted later systematizers (such as [[Sima Qian]]) to group them into a single intellectual lineage. | |

| − | *Dao as the origin of things: "Dao begets one; One begets two; Two begets three; Three begets the myriad creatures." (TTC 42, tr. Lau | + | The [[Dao De Jing]], a text credited to [[Laozi]], is ostensibly the first of these sources. It ascribes three separate metaphysical characteristics to the ''Dao'': |

| + | *Dao as the origin of things: "Dao begets one; One begets two; Two begets three; Three begets the myriad creatures." (TTC 42, tr. Lau) | ||

*Dao as an inexhaustible nothingness: "The Way is like an empty vessel / That yet may be drawn from / Without ever needing to be filled." (TTC 4, tr. Waley) | *Dao as an inexhaustible nothingness: "The Way is like an empty vessel / That yet may be drawn from / Without ever needing to be filled." (TTC 4, tr. Waley) | ||

| − | *Dao | + | *Dao as omnipotent and infallible force: "What Dao plants cannot be plucked, what Dao clasps, cannot slip." (TTC 54, tr. Waley) |

| − | + | The view of the ''Way'' espoused in the ''[[Dao De Jing]],'' which came to influence much later Chinese thought, is eloquently summarized by Livia Kohn: | |

| + | <blockquote>The Tao, if we then try to grasp it, can be described as the organic order underlying and structuring and pervading all existence. It is organic in that it is not willful, but it is also order because it changes in predictable rhythms and orderly patterns. If one is to approach it, reason and intellect have to be left behind. One can only intuit it when one has become as nameless and as free of conscious choices and evaluations as the Tao itself.</blockquote> | ||

| + | <blockquote>The Tao cannot be described in ordinary language, since language by its very nature is part of teh realm of discrimination and knowledge that the Tao transcends. Language is a product of the world; the Tao is beyond it—however pervasive and omnipresent it may be. The Tao is transcendent yet immanent. It creates, structures, orders the whole universe, yet it is not a mere part of it.<ref>Livia Kohn. ''The Taoist Experience: An Anthology.'' (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1993), 11.</ref></blockquote> | ||

| − | + | These metaphysical notions of the Dao are echoed in the [[Zhuangzi]], which states: | |

| + | <blockquote>The Way has its reality and its signs but is without action or form. You can hand it down but you cannot receive it; you can get it but you cannot see it. It is its own source, its own root. Before Heaven and earth existed it was there, firm from ancient times. It gave spirituality to the spirits and to God; it gave birth to Heaven and to earth. It exists beyond the highest point, and yet you cannot call it lofty; it exists beneath the limit of the six directions, and yet you cannot call it deep. It was born before Heaven and earth, and yet you cannot say it has been there for long; it is earlier than the earliest time, and yet you cannot call it old (Zhuangzi ch. 6, BW 77).</blockquote> | ||

| − | ==Dao in | + | ===Dao in Practice=== |

| + | ====Philosophical Daoism==== | ||

| + | :''See also'': [[Laozi]], [[Dao De Jing]], [[Zhuangzi]], [[Liezi]], [[wu-wei]], [[ziran]] | ||

| + | Given a cosmological schema centered on the Dao, it is unsurprising that this notion was also central to the Daoist understanding of human ethics. Specifically, this understanding emerged from the conception that the [[ziran|natural]] operations of the cosmos were perverted by the desires of human beings. Thus, "morality" (understood broadly) consisted of banishing these desires in favor of unimpeded naturalness in thought and action. | ||

| − | + | This issue is addressed by Laozi, who contrasts the Great Way of the ''Dao'' with the way of [[human beings]]: | |

| + | :''The Dao of heaven is to take from those who have too much and give to those who do not have enough. Man’s way is different. He takes from those who do not have enough to give to those who already have too much.'' (verse 77. Tr. Gia Fu Feng) | ||

| + | Further, he characterizes the Way of Man as one in which force is applied without the attainment of desired results: | ||

| + | <blockquote> ''Whenever you advise a ruler in the way of Dao, counsel him not to use force to conquer the universe. For this would only cause resistance. Thorn bushes spring up wherever the army has passed. Lean years follow in the wake of war. Just do what needs to be done. Never take advantage of power…Force is followed by loss of strength. This is not the way of Dao. That which goes against the Dao comes to an early end.'' (verse 30. tr. Gia Fu Feng)</blockquote> | ||

| + | This view was echoed by [[Zhuangzi]], who argued that attempts to assign values and categories are fundamentally contrary to the natural functioning of the world. As such, he suggests that “because right and wrong [i.e. discursive judgment] appeared, the Way was injured” (Zhuangzi ch. 2, BW 37). | ||

| − | + | As such, the correct mode of action is one which does not rely on these attitudes and discriminations. For this reason, a common theme in [[Daoism|Daoist]] literature is that fulfillment in life cannot be attained by forcing one's own destiny; instead, one must be receptive to the path laid for them by nature and circumstance. This led to the formulation of the doctrine of "non-action" ''([[wu-wei]]),'' which describes the harmonization of one’s personal will with the natural harmony and justice of Nature. Describing this path, the ''Dao De Jing'' states: "The World is ruled by letting things take their natural course. It cannot be ruled by going against nature or arrogance" (48).<ref>See also Zhuangzi's discussion of [[Zhuangzi#Wu-wei|wu-wei]].</ref> Likewise, it also suggests that this mode of action yields ubiquitously positive results, as it allows everything to develop to its full, untrammeled potential: | |

| − | + | <blockquote>Dao abides in non-action yet nothing is left undone. If kings and lords observed this, the ten thousand things would develop naturally. If they still desired to act they would return to the simplicity of formless substance. Without form there is no desire. Without desire there is tranquility. And in this way all things would be at peace. (''[[Dao De Jing]]'' (37))</blockquote> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | This path of practice is also advocated in the [[Liezi]], a later text in the philosophical corpus: | |

| − | + | <blockquote>The highest man at rest is as though dead, in movement is like a machine. He knows neither why he is at rest nor why he is not, why he is in movement nor why he is not. He neither changes his feelings and expression because ordinary people are watching, nor fails to change them because ordinary people are not watching. He comes alone and goes alone, comes out alone and goes in alone; what can obstruct him? (Liezi. ch. 6, Graham 130)</blockquote> | |

| − | + | As mentioned above, it should be noted that in Daoism the complementary part of "non-action" ''([[wu-wei]])'' is that nothing necessary is left undone ("''wu bu wei''"). Thus, Daoism should be viewed as advocating the harmonization of "passivity" and "activity/creativity" instead of just being passive. In other words through stillness and receptivity natural intuition guides us in knowing when to act and when not to act. Remembering the Great Way is a spiritual awareness of one’s deep connection with the entirety of creation. This involves the adoption of a mode of ‘non-action’ that is not inaction but rather a harmonization of one’s personal will – otherwise tending towards egotism – with the natural harmony and justice of Dao. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ====Religious Daoism==== | |

| + | In addition to the philosophical traditions described above, the ethics and metaphysics of Daoism also inspired religious practice. As Kohn notes, "crucial to the religious experience of Taoism, the Tao is always there yet has always to be attained, realized, perfected. It creates the world and remains in it as the seed of primordial harmony, original purity, selfless tranquility."<ref>Kohn, 11.</ref> As such, these notions proved to be instructive for both Chinese [[monasticism]] and religious devotion. | ||

| − | + | The ''praxis''-based application of Daoist metaphysics can be seen in the ''Qingjing jing'' ("Scripture of Purity and Tranquility"), a central text of the [[Quanzhen]] school of [[Daoism]]: | |

| − | : | + | :The Tao can be pure or turbid, moving or tranquil. |

| + | :Heaven is pure, earth is turbid; | ||

| + | :Heaven is moving, earth is tranquil. | ||

| + | :The male is moving, the female is tranquil. | ||

| + | : | ||

| + | :Descending from the origin, | ||

| + | :Flowing toward the end, | ||

| + | :The myriad beings are being born. | ||

| + | :... | ||

| + | :The human spirit is fond of purity, | ||

| + | :But the mind disturbs it. | ||

| + | :The human mind is fond of tranquility, | ||

| + | :But desires meddle with it. | ||

| + | : | ||

| + | :Get rid of desires for good, | ||

| + | :And the mind will be calm. | ||

| + | :Cleanse your mind, | ||

| + | :And the spirit will be pure.<ref>''Qingjing Jing,'' translated in Kohn, 26-27.</ref> | ||

| − | + | ==Dao in Later Thought== | |

| + | Once the metaphysical notion of the ''Dao'' was entrenched in the philosophical mainstream, it was applied throughout Chinese philosophical and religious thought. For instance, the earliest translators of [[Buddhism|Buddhist]] [[sutra]]s into Chinese chose it as a worthy analog of the Sanskrit ''[[dharma]]''.<ref>Arthur F. Wright. ''Buddhism in Chinese History.'' (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1959), 36.</ref> Likewise, the [[Neo-Confucianism|Neo-Confucian]] movement, which syncretically applied Buddhist and Daoist metaphysics to classical Confucian morality, also inherited this cosmological perspective. Specifically, [[Zhou Dunyi]]'s ''Diagram of the Supreme Ultimate'' is credited for outlining "the parameters in which the yin-yang theory was to be assimilated metaphysically and systematically into Confucian thought and practice." <ref>Robin Wang, "Zhou Dunyi's Diagram of the Supreme Ultimate Explained (Taijitu shuo): A Construction of the Confucian Metaphysics." ''Journal of the History of Ideas'' 66 (3) (July 2005): 307</ref> <ref> Chan 1963, 460.</ref> | ||

| − | " | + | In the modern world, some scientists suggest that there is a creative principle at work in the universe that causes naturally occurring phenomena to organize themselves into complex interdependent systems. This "principle of self-organization" is sometimes termed ''Dao.'' <ref>See, for example, Fritjof Capra. ''The Tao of Physics: An Exploration of the Parallels between Modern Physics and Eastern Mysticism.'' (Boston: Shambhala, 2000).</ref> |

| − | + | ==Notes== | |

| + | {{reflist}} | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | * Capra, Fritjof. ''The Tao of Physics: An Exploration of the Parallels between Modern Physics and Eastern Mysticism. Boston: Shambhala, 2000. ISBN 1570625190. | + | * Capra, Fritjof. ''The Tao of Physics: An Exploration of the Parallels between Modern Physics and Eastern Mysticism.'' Boston: Shambhala, 2000. ISBN 1570625190 |

| − | * Chang, Dr. Stephen T. ''The Great Tao.'' Tao Publishing, imprint of Tao Longevity LLC | + | * Chan, Wing-tsit. ''A Source Book in Chinese Philosophy.'' Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1969 (original 1963). ISBN 0691019649 |

| − | *Graham, A.C. ''Disputers of the Tao: Philosophical Argument in Ancient China'' | + | * Chang, Dr. Stephen T. ''The Great Tao.'' Tao Publishing, imprint of Tao Longevity LLC, 1985. ISBN 0942196015 |

| − | * ''Lao Tsu/Tao Te Ching'' | + | *Graham, A.C. ''Disputers of the Tao: Philosophical Argument in Ancient China.'' La Salle, IL: Open Court, 1993. ISBN 0812690877. |

| − | * Lao Tzu; Lau, D.C. ( | + | * Graham, A.C. (trans.). ''The Book of Lieh-tzǔ: A Classic of Tao.'' New York: Columbia University Press. 1960, revised 1990. ISBN 0231072376 |

| − | * Lao Tzu; Chuang Tzu; Legge, James (translator), ''The Sacred Books of China: The Texts of Taoism'' | + | * Kohn, Livia. ''The Taoist Experience: An Anthology.'' Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1993. ISBN 0791415805. |

| − | * Quong, Rose ''Chinese Characters: Their Wit and Wisdom.'' With Illustrations by Dr. Kinn Wei Shaw. Ram Press, 1944. | + | * ''Lao Tsu/Tao Te Ching,'' translated by Gia-Fu Feng & Jane English. New York: Vintage Books, 1972. ISBN 0679776192 |

| − | * | + | * Lao Tzu; Lau, D.C. (trans.); Sarah Allan (ed.). ''Tao Te Ching: Translation of the Ma Wang Tui Manuscripts.'' Everyman's Library, 1994. ISBN 0679433163 |

| + | * Lao Tzu; Chuang Tzu; Legge, James (translator), ''The Sacred Books of China: The Texts of Taoism.'' Dover Publications, Inc., 1962. | ||

| + | * Quong, Rose. ''Chinese Characters: Their Wit and Wisdom.'' With Illustrations by Dr. Kinn Wei Shaw. Ram Press, 1944. | ||

| + | * ''The Analects of Confucius,'' translated and with an introduction by Roger T. Ames and Henry Rosemont, Jr. New York: Ballantine Books, 1998. ISBN 0345434072 | ||

| + | * Wang, Robin. "Zhou Dunyi's Diagram of the Supreme Ultimate Explained (Taijitu shuo): A Construction of the Confucian Metaphysics." ''Journal of the History of Ideas'' 66(3) (July 2005): 307–323. | ||

| + | * Watson, Burton (trans.). ''Chuang Tzu: Basic Writings.'' New York: Columbia University Press, 1996 (original 1969). ISBN 0231105959 | ||

| + | * Wright, Arthur F. ''Buddhism in Chinese History.'' Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1959. ISBN 0804705488 | ||

== External links == | == External links == | ||

| − | + | All links retrieved June 23, 2022. | |

| − | * [http://www.tao-te-king.org/index.html Dao De Jing translations (Dr.Hilmar KLAUS) | + | * [http://www.tao-te-king.org/index.html Dao De Jing translations] (Dr.Hilmar KLAUS) |

| − | |||

*[http://www.taoism-directory.org/ Taoism Directory], directory of sites with content related to Taoism and Taoist issues. | *[http://www.taoism-directory.org/ Taoism Directory], directory of sites with content related to Taoism and Taoist issues. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

[[Category:Philosophy and religion]] | [[Category:Philosophy and religion]] | ||

Latest revision as of 19:34, 7 July 2023

|

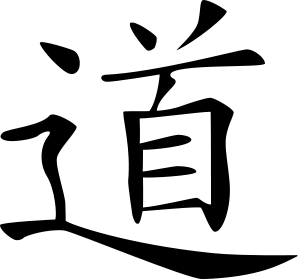

| Composition 1: 道 (dào) is 首 (shǒu) 'head' and 辶 (辵 chuò) 'go' (Source: Wenlin) |

| Pinyin: Dào |

| Wade-Giles: Tao |

| Japanese: Dō, (tō), michi |

| Korean: 도 (To) |

| Vietnamese: Đạo |

Tao or Dao (道, Pinyin: Dào, Cantonese: Dou) is a Chinese character often translated as ‘Way’ or 'Path'. Though often seen as a linguistic monad (especially by Westerners), the character dao was often modified by other nouns, each of which represented a subset of the terms multifarious meanings. Three such compounds gained special currency in classical Chinese philosophy: 天道 Tian dao (sky or natural dao—usually translated religiously as "heaven's Dao") 大道 Da Dao (Great dao—the actual course of all history—everything that has happened or will happen) and 人道 Ren dao (human dao, the normative orders constructed by human (social) practices). The natural dao corresponds roughly to the order expressed in the totality of natural (physical) laws. The relationship between these three was one of the central subjects of the discourses of Laozi, Zhuangzi, and many other Chinese philosophers.

From the earliest recorded religio-philosophical texts onward, Tian Dao is explained using the concepts of yin and yang. The resulting cosmology became a distinctive feature of Chinese philosophy, one which was particularly expounded upon by members of the Daoist school. The early thinkers, Laozi and Zhuangzi, expressed the view that human dao was embedded in natural dao. If human lives are lived in accord with the natural order of reality, then human beings can truly fulfill their innate potentialities.

Etymology

The composition of 道 (dào) is 首 (shǒu) meaning "head" and 辶 (辵 chuò) "go." The decomposition etymology for the character 首 is distinguished by the tufts at the top, representing the distinctive hairstyle of the warrior class (a "bun"). The character 首 itself is used to refer to concepts related to the head, such as leadership and rulership. The character 辶 (辵 chuò) 'go' in its reduced form, 廴 resembles a foot, and is meant to be evocative of its meaning "to walk," and "to go," as well as the generic radix for "the way of." This reduced radical 廴 is a component in other radicals and characters. As such, the combined characters signify directed, forward movement (and perhaps even "process" in a Whiteheadian sense).[1] [2] See also: [3]

Dao in an Early Chinese Context

- See: Confucius, Confucianism

Though the concept of Dao is most often understood in light of its Daoist exponents, the term was actually an important element of Chinese religio-philosophical discourse since time immemorial. However, these thinkers almost exclusively utilized in the human context (ren dao 人道) rather than the cosmological notion that came to dominate later usage. The clearest example of this early understanding can be seen in the Analects of Confucius.

In this formative text, the Master Kong uses dao to describe the optimal, praxis-based path for individual aspirants and the verbal act of following that path (a distinction that relies on the grammatical ambiguity of classical Chinese). This path is open to all people, but is dependent upon heartfelt study of the Five Classics and internalization of the rules of ritual propriety (li). As described in Ames and Rosemont's masterful introduction to the Analects, "to realize the dao is to experience, to interpret, and to influence the world in such a way as to reinforce and extend the way of life inherited from one's cultural predecessors. This way of living in the world then provides a road map and direction for one's cultural successors."[4] Inherent in this notion is the view that following (or embodying) the dao is a difficult process requiring constant study and effort:

- Ranyou said, "It is not that I do not rejoice in the way (dao) of the Master, but that I do not have the strength to walk it."

- The Master said, "Those who do not have the strength for it collapse somewhere along the way. But with you, you have drawn your own line before you start" (6.12).

Another distinctive element of the Confucian Dao is that it is particularistic: different disciples are given specific instruction based upon their innate qualities and characteristics:

- Gongxi Hua said, "When Zilu asked the question, you observed that his father and elder brothers are still alive, but when Ranyou asked the same question, you told him to act on what he learns. I am confused—could you explain this to me?"

- The Master replied, "Ranyou is diffident, and so I urged him on. But Zilu has the energy of two, and so I sought to rein him in" (11.22).

In this way, while the dao is interpreted as a single path (that one is either walking or has strayed from), it is still adapted to each individual's aptitudes. In this context, harmonious behavior results from the optimizing one's tendencies and attitudes through the emulation of classical models: a moral vision that is most clearly described in the Zhong Yong (Doctrine of the Mean).

A. C. Graham's Disputers of the Tao elegantly summarizes the Confucian dao: "the Way is mentioned explicitly only as the proper course of human conduct and government. Indeed he think of it as itself widened by the broadening of human culture: 'Man is able to enlarge the Way [dao], it is not that the Way enlarges man' (15.29)."[5] However, he also notes a single passage in the Analects that could presuppose a Daoist understanding of the cosmos (17.19), stating that it "implies a fundamental unity of Heaven and man. [As such,] it suggests that with the perfect ritualisation of life we would understand our place in community and cosmos without the need of words." [6] This humanistic understanding was prevalent in the pre-Daoist period.

This being said, the fact that most key terms (i.e., dao, de, tian, wu-wei) were shared throughout the religious and philosophical corpora meant that later developments and modifications had considerable significance, even outside their tradition of origin. For instance, Neo-Confucian thought expanded the classical understanding of dao by including Daoist-inspired cosmological notions (as discussed below).

Dao in the Daoist Context

- See also: Laozi, Dao De Jing, Zhuangzi

Unlike other early Chinese thinkers, the philosophers who came to be retroactively identified as Daoists stressed the self-ordering simplicity of the natural world as a logical corrective for the problems plaguing human life. This naturalistic connection was commented on at length by both Laozi and Zhuangzi, as well as later philosophers such as Liezi, Ge Hong and Wang Bi.

The concept of Dao is based upon the understanding that the only constant in the universe is change (see I Jing, the "Book of Changes") and that we must understand and attempt to harmonize ourselves with this change. Change is characterized as a constant progression from non-being into being, potential into actual, yin into yang, female into male. This understanding is first suggested in the Yi Jing, which states that "one (phase of) Yin, one (phase of) Yang, is what is called the Dao." Being thus placed at the conjunction of the alternation of yin and yang, the Dao can be understood as the continuity principle that underlies the constant evolution of the world. For this reason, the Dao is often symbolized by the Taijitu (yin-yang), which represents the yin (darkness) and yang (brightness) mutually generating and interpenetrating in an endless cycle.[7]

In this context, the Daoist school began to extrapolate upon the metaphysical nature of this universal force. Though its various exponents addressed discrete elements of the Dao, their common focus is what permitted later systematizers (such as Sima Qian) to group them into a single intellectual lineage.

The Dao De Jing, a text credited to Laozi, is ostensibly the first of these sources. It ascribes three separate metaphysical characteristics to the Dao:

- Dao as the origin of things: "Dao begets one; One begets two; Two begets three; Three begets the myriad creatures." (TTC 42, tr. Lau)

- Dao as an inexhaustible nothingness: "The Way is like an empty vessel / That yet may be drawn from / Without ever needing to be filled." (TTC 4, tr. Waley)

- Dao as omnipotent and infallible force: "What Dao plants cannot be plucked, what Dao clasps, cannot slip." (TTC 54, tr. Waley)

The view of the Way espoused in the Dao De Jing, which came to influence much later Chinese thought, is eloquently summarized by Livia Kohn:

The Tao, if we then try to grasp it, can be described as the organic order underlying and structuring and pervading all existence. It is organic in that it is not willful, but it is also order because it changes in predictable rhythms and orderly patterns. If one is to approach it, reason and intellect have to be left behind. One can only intuit it when one has become as nameless and as free of conscious choices and evaluations as the Tao itself.

The Tao cannot be described in ordinary language, since language by its very nature is part of teh realm of discrimination and knowledge that the Tao transcends. Language is a product of the world; the Tao is beyond it—however pervasive and omnipresent it may be. The Tao is transcendent yet immanent. It creates, structures, orders the whole universe, yet it is not a mere part of it.[8]

These metaphysical notions of the Dao are echoed in the Zhuangzi, which states:

The Way has its reality and its signs but is without action or form. You can hand it down but you cannot receive it; you can get it but you cannot see it. It is its own source, its own root. Before Heaven and earth existed it was there, firm from ancient times. It gave spirituality to the spirits and to God; it gave birth to Heaven and to earth. It exists beyond the highest point, and yet you cannot call it lofty; it exists beneath the limit of the six directions, and yet you cannot call it deep. It was born before Heaven and earth, and yet you cannot say it has been there for long; it is earlier than the earliest time, and yet you cannot call it old (Zhuangzi ch. 6, BW 77).

Dao in Practice

Philosophical Daoism

Given a cosmological schema centered on the Dao, it is unsurprising that this notion was also central to the Daoist understanding of human ethics. Specifically, this understanding emerged from the conception that the natural operations of the cosmos were perverted by the desires of human beings. Thus, "morality" (understood broadly) consisted of banishing these desires in favor of unimpeded naturalness in thought and action.

This issue is addressed by Laozi, who contrasts the Great Way of the Dao with the way of human beings:

- The Dao of heaven is to take from those who have too much and give to those who do not have enough. Man’s way is different. He takes from those who do not have enough to give to those who already have too much. (verse 77. Tr. Gia Fu Feng)

Further, he characterizes the Way of Man as one in which force is applied without the attainment of desired results:

Whenever you advise a ruler in the way of Dao, counsel him not to use force to conquer the universe. For this would only cause resistance. Thorn bushes spring up wherever the army has passed. Lean years follow in the wake of war. Just do what needs to be done. Never take advantage of power…Force is followed by loss of strength. This is not the way of Dao. That which goes against the Dao comes to an early end. (verse 30. tr. Gia Fu Feng)

This view was echoed by Zhuangzi, who argued that attempts to assign values and categories are fundamentally contrary to the natural functioning of the world. As such, he suggests that “because right and wrong [i.e. discursive judgment] appeared, the Way was injured” (Zhuangzi ch. 2, BW 37).

As such, the correct mode of action is one which does not rely on these attitudes and discriminations. For this reason, a common theme in Daoist literature is that fulfillment in life cannot be attained by forcing one's own destiny; instead, one must be receptive to the path laid for them by nature and circumstance. This led to the formulation of the doctrine of "non-action" (wu-wei), which describes the harmonization of one’s personal will with the natural harmony and justice of Nature. Describing this path, the Dao De Jing states: "The World is ruled by letting things take their natural course. It cannot be ruled by going against nature or arrogance" (48).[9] Likewise, it also suggests that this mode of action yields ubiquitously positive results, as it allows everything to develop to its full, untrammeled potential:

Dao abides in non-action yet nothing is left undone. If kings and lords observed this, the ten thousand things would develop naturally. If they still desired to act they would return to the simplicity of formless substance. Without form there is no desire. Without desire there is tranquility. And in this way all things would be at peace. (Dao De Jing (37))

This path of practice is also advocated in the Liezi, a later text in the philosophical corpus:

The highest man at rest is as though dead, in movement is like a machine. He knows neither why he is at rest nor why he is not, why he is in movement nor why he is not. He neither changes his feelings and expression because ordinary people are watching, nor fails to change them because ordinary people are not watching. He comes alone and goes alone, comes out alone and goes in alone; what can obstruct him? (Liezi. ch. 6, Graham 130)

As mentioned above, it should be noted that in Daoism the complementary part of "non-action" (wu-wei) is that nothing necessary is left undone ("wu bu wei"). Thus, Daoism should be viewed as advocating the harmonization of "passivity" and "activity/creativity" instead of just being passive. In other words through stillness and receptivity natural intuition guides us in knowing when to act and when not to act. Remembering the Great Way is a spiritual awareness of one’s deep connection with the entirety of creation. This involves the adoption of a mode of ‘non-action’ that is not inaction but rather a harmonization of one’s personal will – otherwise tending towards egotism – with the natural harmony and justice of Dao.

Religious Daoism

In addition to the philosophical traditions described above, the ethics and metaphysics of Daoism also inspired religious practice. As Kohn notes, "crucial to the religious experience of Taoism, the Tao is always there yet has always to be attained, realized, perfected. It creates the world and remains in it as the seed of primordial harmony, original purity, selfless tranquility."[10] As such, these notions proved to be instructive for both Chinese monasticism and religious devotion.

The praxis-based application of Daoist metaphysics can be seen in the Qingjing jing ("Scripture of Purity and Tranquility"), a central text of the Quanzhen school of Daoism:

- The Tao can be pure or turbid, moving or tranquil.

- Heaven is pure, earth is turbid;

- Heaven is moving, earth is tranquil.

- The male is moving, the female is tranquil.

- Descending from the origin,

- Flowing toward the end,

- The myriad beings are being born.

- ...

- The human spirit is fond of purity,

- But the mind disturbs it.

- The human mind is fond of tranquility,

- But desires meddle with it.

- Get rid of desires for good,

- And the mind will be calm.

- Cleanse your mind,

- And the spirit will be pure.[11]

Dao in Later Thought

Once the metaphysical notion of the Dao was entrenched in the philosophical mainstream, it was applied throughout Chinese philosophical and religious thought. For instance, the earliest translators of Buddhist sutras into Chinese chose it as a worthy analog of the Sanskrit dharma.[12] Likewise, the Neo-Confucian movement, which syncretically applied Buddhist and Daoist metaphysics to classical Confucian morality, also inherited this cosmological perspective. Specifically, Zhou Dunyi's Diagram of the Supreme Ultimate is credited for outlining "the parameters in which the yin-yang theory was to be assimilated metaphysically and systematically into Confucian thought and practice." [13] [14]

In the modern world, some scientists suggest that there is a creative principle at work in the universe that causes naturally occurring phenomena to organize themselves into complex interdependent systems. This "principle of self-organization" is sometimes termed Dao. [15]

Notes

- ↑ See Wenlin, 1997-2007 Wenlin Institute. Retrieved March 25, 2008.

- ↑ The Analects of Confucius, Translated and with an introduction by Roger T. Ames and Henry Rosemont, Jr. (New York: Ballantine Books, 1998), 45

- ↑ "Dao" at [zhongwen.com zhongwen.com], which lists the etymology as a combination of "movement" and "ahead."

- ↑ Ames and Rosemont, 45.

- ↑ A. C. Graham. Disputers of the Tao: Philosophical Argument in Ancient China. (La Salle, IL: Open Court, 1993), 18.

- ↑ Graham 1993

- ↑ See Wing-tsit Chan. A Source Book in Chinese Philosophy. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press), 262-263 for a concise introduction to the Dao De Jing.

- ↑ Livia Kohn. The Taoist Experience: An Anthology. (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1993), 11.

- ↑ See also Zhuangzi's discussion of wu-wei.

- ↑ Kohn, 11.

- ↑ Qingjing Jing, translated in Kohn, 26-27.

- ↑ Arthur F. Wright. Buddhism in Chinese History. (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1959), 36.

- ↑ Robin Wang, "Zhou Dunyi's Diagram of the Supreme Ultimate Explained (Taijitu shuo): A Construction of the Confucian Metaphysics." Journal of the History of Ideas 66 (3) (July 2005): 307

- ↑ Chan 1963, 460.

- ↑ See, for example, Fritjof Capra. The Tao of Physics: An Exploration of the Parallels between Modern Physics and Eastern Mysticism. (Boston: Shambhala, 2000).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Capra, Fritjof. The Tao of Physics: An Exploration of the Parallels between Modern Physics and Eastern Mysticism. Boston: Shambhala, 2000. ISBN 1570625190

- Chan, Wing-tsit. A Source Book in Chinese Philosophy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1969 (original 1963). ISBN 0691019649

- Chang, Dr. Stephen T. The Great Tao. Tao Publishing, imprint of Tao Longevity LLC, 1985. ISBN 0942196015

- Graham, A.C. Disputers of the Tao: Philosophical Argument in Ancient China. La Salle, IL: Open Court, 1993. ISBN 0812690877.

- Graham, A.C. (trans.). The Book of Lieh-tzǔ: A Classic of Tao. New York: Columbia University Press. 1960, revised 1990. ISBN 0231072376

- Kohn, Livia. The Taoist Experience: An Anthology. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1993. ISBN 0791415805.

- Lao Tsu/Tao Te Ching, translated by Gia-Fu Feng & Jane English. New York: Vintage Books, 1972. ISBN 0679776192

- Lao Tzu; Lau, D.C. (trans.); Sarah Allan (ed.). Tao Te Ching: Translation of the Ma Wang Tui Manuscripts. Everyman's Library, 1994. ISBN 0679433163

- Lao Tzu; Chuang Tzu; Legge, James (translator), The Sacred Books of China: The Texts of Taoism. Dover Publications, Inc., 1962.

- Quong, Rose. Chinese Characters: Their Wit and Wisdom. With Illustrations by Dr. Kinn Wei Shaw. Ram Press, 1944.

- The Analects of Confucius, translated and with an introduction by Roger T. Ames and Henry Rosemont, Jr. New York: Ballantine Books, 1998. ISBN 0345434072

- Wang, Robin. "Zhou Dunyi's Diagram of the Supreme Ultimate Explained (Taijitu shuo): A Construction of the Confucian Metaphysics." Journal of the History of Ideas 66(3) (July 2005): 307–323.

- Watson, Burton (trans.). Chuang Tzu: Basic Writings. New York: Columbia University Press, 1996 (original 1969). ISBN 0231105959

- Wright, Arthur F. Buddhism in Chinese History. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1959. ISBN 0804705488

External links

All links retrieved June 23, 2022.

- Dao De Jing translations (Dr.Hilmar KLAUS)

- Taoism Directory, directory of sites with content related to Taoism and Taoist issues.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.