Difference between revisions of "Czechoslovakia" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 63: | Line 63: | ||

* 1990–1992: a federal democratic republic consisting of the ''Czech Republic'' and the ''Slovak Republic'' | * 1990–1992: a federal democratic republic consisting of the ''Czech Republic'' and the ''Slovak Republic'' | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

== History == | == History == | ||

| Line 154: | Line 148: | ||

The June 1990 elections uncovered the growing rift between the two countries when Slovakia openly challenged President Havel's intervening in Slovak internal affairs. While the conservative Civic Democratic Party (ODS) won a sweeping victory in the Czech Republic, Slovakia voted in the liberal Movement for a Democratic Slovakia (HZDS). The cabinets of both countries were no longer composed of mostly former dissidents, and although the federal government operated on the principle of symmetric power-sharing, disagreements between the republics escalated into Slovakia’s declaration of a sovereign state in July 1992, whereby its laws overrode the federal laws. Negotiations on the dissolution of the federal state took place for the rest of the year, which was materialized on January 1, 1993, when two independent states—[[Slovakia]] and the [[Czech Republic]]—appeared on the map of [[Europe]]. | The June 1990 elections uncovered the growing rift between the two countries when Slovakia openly challenged President Havel's intervening in Slovak internal affairs. While the conservative Civic Democratic Party (ODS) won a sweeping victory in the Czech Republic, Slovakia voted in the liberal Movement for a Democratic Slovakia (HZDS). The cabinets of both countries were no longer composed of mostly former dissidents, and although the federal government operated on the principle of symmetric power-sharing, disagreements between the republics escalated into Slovakia’s declaration of a sovereign state in July 1992, whereby its laws overrode the federal laws. Negotiations on the dissolution of the federal state took place for the rest of the year, which was materialized on January 1, 1993, when two independent states—[[Slovakia]] and the [[Czech Republic]]—appeared on the map of [[Europe]]. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

== From Creation to Dissolution — Overview == | == From Creation to Dissolution — Overview == | ||

Revision as of 20:13, 8 July 2007

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

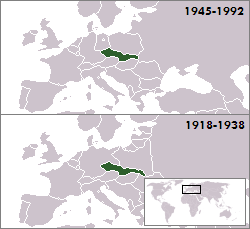

Czechoslovakia (Czech and Slovak: Československo, or (increasingly after 1990) in Slovak Česko-Slovensko) was a country in Central Europe that existed from October 28, 1918, when it declared independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, until 1992, with a brief intermezzo during World War II. On January 1, 1993, Czechoslovakia split into the Czech Republic and Slovakia. During the 74 years of its existence, it saw several changes in the political and economic climate, the longest one being as a satellite of the Communist Soviet Union with a centrally planned economy. It consisted of two predominant ethnic groups—Czechs and Slovaks—both of the Slavic origin, with the population and geographic split roughly 2:1. Although Czechs and Slovaks had had different histories, they envisioned the joint state as a vehicle toward peace and the leveling of economic discrepancies, as articulated by Thomas Garrigue Masaryk, who became the country's first president. World War II interrupted the coexistence, with Slovakia declaring independence as an ally of the Nazi Germany and the Czech lands handed over to Hitler by the Allies to appease his expansionism. Czechoslovakia was liberated mostly by the Red Army and subsequently fell under the Soviet sphere of influence. With Communists gradually gaining a firm grip, it was only a natural step that the country rejected Marshall Plan, joined Warsaw Pact, nationalized private businesses and property, and introduced central economic planning. The infamous Cold War period was interrupted by the economic and political reforms of the Prague Spring in 1968 – the only glimpse of hope that was quickly quashed by the invading Warsaw Pact armies with an exception of Romania. In November 1989, Czechoslovakia joined the wave of anti-Communist uprisings throughout the Eastern Bloc and embraced democracy, with dissident Václav Havel becoming the first president. Addressing the Communist legacy, both in political and economic terms, was a painful process accompanied by escalated nationalism in Slovakia and a mounting sense of unfair economic treatment of Slovakia by the Czechs, which drove Czechoslovakia toward the peaceful split labeled Velvet Divorce.

Basic Facts

Form of statehood:

- 1918–1938: democratic republic

- 1938–1939: after annexation of the Sudetenland region by Germany in 1938, Czechoslovakia turned into a state with loosened connections between its Czech, Slovak and Ruthenian parts. A large strip of southern Slovakia and Ruthenia was annexed by Hungary, while the Zaolzie region went under Poland's control

- 1939–1945: split into the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia and the independent Slovakia, although Czechoslovakia per se was never officially dissolved; its exiled government, recognized by the Western Allies, was based in London.

- 1945–1948: democracy, governed by a coalition government, with Communist ministers charting the course

- 1948–1989: Communist state with a centrally planned economy

- 1960 on: the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic

- 1969–1990: federal republic consisting of the Czech Socialist Republic and the Slovak Socialist Republic

- 1990–1992: a federal democratic republic consisting of the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic

History

Inception of Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia came into existence in October 1918 as one of the successor states of Austria-Hungary following the end of World War I, comprising the territory of the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Carpathian Ruthenia and some of the most industrialized regions of the former Austria-Hungary. The Austro-Hungarian Empire had been slowly losing ground to nationalist movements in the final years of the war, a development that was facilitated by US President Woodrow Wilson's demand in January 1918 that the monarchy allow for the self-determination of its peoples as part of his Fourteen Points. Emperor Charles I allowed each national group to exercise self-governance as part of a confederation; however, these concessions only advanced the real objective of each national government, that is, complete independence. The document was drawn up by Thomas Garrigue Masaryk, who gained support of expatriate Czechs and Slovaks around the common goal of a joint state and was the driving force behind the Czechoslovak resistance movement. The proclamation was a blueprint for the constitution of the state-in-the-works, promising broad democratic rights and freedoms, separation of state from Church, expropriation of land, and abolishment of the class system.

On October 28, 1918, Alois Rašín, Antonín Švehla, František Soukup, Jiří Stříbrný, and Vavro Šrobár, the "Men of October 28th", formed a provisional government, and two days later, Slovakia endorsed the marriage of the two countries, with Masaryk elected president.

World War II

End of State

Satisfaction among individual ethnic groups within the new state varied, as Germans, Slovaks, and Slovakia's ethnic Hungarians grew resentful of the political and economic dominance of the Czechs who were reluctant to safeguard political autonomy for all of the country’s constituents. This policy, combined with an increasing Nazi propaganda, particularly in the industrialized German speaking Sudetenland (the German-border regions of Bohemia and Moravia), where there were voices for the creation of a new province, Deutschösterreich (German Austria) and later Deutschböhmen (German Bohemia), fueled the growing unrest in the years leading up to World War II.[1] Following the Anschluss', when Germany annexed Austria, the Sudetenland would be Adolf Hitler's next demand. The Munich Agreement, signed on September 29, 1938, by the representatives of Germany—Hitler, Great Britain—Neville Chamberlain, Italy—Benito Mussolini, and France—Édouard Daladier, robbed Czechoslovakia of one-third of its territory, mainly the Sudetenland, where most of the border defenses were situated. Within ten days, 1,200,000 Czechs and Slovaks living in the region were told to leave their homes, and the severely weakened Czechoslovak Republic was forced to grant major concessions to the non-Czechs. Czechoslovak President Edvard Beneš resigned on October 5, 1938, and Emil Hácha, a highly respected lawyer by training and independent thinker, was appointed president. Hitler thus defeated Czechoslovakia without taking up arms. In November, a strip of southern Slovakia was handed over to Hungary.

On March 14, 1939, Hácha set out for Berlin to meet with Hitler; on the same day, Slovakia declared independence and became an ally of Nazi Germany. Slovakia’s independence played into Hitler’s hands by providing him with a pretext to occupy Bohemia and Moravia on grounds that Czechoslovakia had collapsed from within; therefore, the administration of the Czech lands would forestall chaos in Central Europe. Hácha described the signing away of Czechoslovakia to Nazi Germany, for which he had been traditionally labeled as national traitor, as follows: “It’s possible to withstand Hitler’s yelling, because a person who yells is not necessarily a devil. But Göring [Hitler’s right hand], with his jovial face, was there as well. He took me by the hand and softly reproached me, asking whether it is really necessary for the beautiful Prague to be leveled in a few hours… and I could tell that the devil, able to carry out his threat, was speaking to me.”[2] Göring further asked Hácha: “You do not want or cannot understand the Führer, who wishes that lives of thousands of Czech people are spared?”[3]

The president had been subjected to enormous psychological pressure in the course of which he collapsed repeatedly. The next morning, Wehrmacht occupied what remained of Czechoslovakia. After Hitler personally inspected the Czech fortifications, he privately admitted that “We would have shed a lot of blood.”[4] Czechoslovakia’s factories thus began churning out equipment for the Third Reich.

Slovakia's troops fought on the Russian front until the summer of 1944, when the Slovak armed forces staged an anti-government uprising that was quickly crushed by Germany.

Resistance Movement

On October 28, 1939, the 21st anniversary of the establishment of the country, Czechoslovakia, emboldened by hopes for an early restoration of the independence, was swept by massive demonstrations. Medical student Jan Opletal was killed in Prague in confrontations with the occupants, which spurred further unrest that led to spontaneous executions of student leaders and the closure of universities. These reprisals signaled that continued open encounter with the occupation forces was not feasible; therefore, resistance movement shifted to underground organizations and networks. The goal of the London-based exiled government, in conjunction with efforts of national and foreign-based Czechoslovak representative offices, was to restore the independent Czechoslovakia. To this end, Czechoslovak units were created in Poland, France, and Great Britain composed of recruits from the ranks of exiled Czechoslovak citizens.

On the home turf, resistance movement continued chiefly through massive demonstrations, which reached an apex in 1941. The society was split in three streams with respect to their stance on the Nazi occupation: the largest chunk of the population comprised those who passively rejected the occupation and would swing both ways. Then there were those who supported the resistance movement, and, lastly, resistance movement groups and organizations seeking the restoration of the independent Czechoslovak Republic. However, widespread arrests severely disrupted the underground networks and cut off radio networks between domestic and foreign components of the resistance movement, which were then reestablished by paratroopers dispatched into the Protectorate.

Operation Anthropoid

The Czechoslovak-British Operation Anthropoid was the code name for the assassination of the top Nazi leader Reinhard Heydrich, the chief of RSHA, an organization that included the Gestapo (Secret Police), SD (Security Agency) and Kripo (Criminal Police). Heydrich was the mastermind of the purge of Hitler's opponents as well as the genocide of Jews. Being a valued political ally, advisor and friend of the dictator, he was involved in most of Hitler's intrigues and was feared by Nazi generals. Thanks to his reputation as the liquidator of resistance movements in Europe, he was sent to Prague in September 1941 to make order as the Protector of Bohemia and Moravia. The Protectorate was of strategic importance to Hitler’s plans, and Heydrich, dubbed the “Butcher of Prague”, "The Blond Beast" or "The Hangman", wasted no time upon his arrival, handing out death sentences for Czech military officials, resistance movement fighters and political figures the day after his arrival.

With the fighting spirit in the Protectorate at lull, the exiled military officials started planning an operation that would stir up the nation’s consciousness — six Czech and one Slovak paratroopers were chosen for the assassination of Heydrich, and two of them— Czech Josef Valčík and Slovak Josef Gabčik, executed it. Heydrich died of complications following surgery. The Gestapo tracked the paratroopers’ contacts and eventually discovered the paratroopers’ hideaway in a Prague church. Three of them died in a shootout while trying to buy time for the others so that they could dig out an escape route. However, the Gestapo found out and used tear gas and water to chase the remaining four out, but the paratroopers used their last bullets to take their lives rather than fall in the Nazi hands alive.

Heydrich’s successor Karl Herrmann Frank had 10,000 Czechs executed as a warning, and two villages that assisted the paratroopers were leveled down, with the adults executed and young children sent to German families for re-education. The combined actions of the Gestapo and its confidantes virtually paralyzed the Czech resistance movement; on the other hand, the assassination bolstered Czechoslovakia’s prestige in the world and was crucial to the country’s securing of demands for an independent republic following the end of WWII.

End of War

Toward the end of the war, partisan movement was gaining momentum, and once the Allies were on the winning side, the political orientation of Czechoslovakia was high on the agenda of the two most influential exiled centres–the government in London and the communist officials in Moscow. Both looked at the agreement on friendship, mutual assistance and postwar cooperation between Czechoslovakia and the Soviet Union as a means to stem German expansion on one hand and the Soviet Union’s mingling into Czechoslovakia's internal affairs on the other. The country was liberated by the Soviet Union's Red Army and partly by the US Army on May 9.

Communist Czechoslovakia

Retaliatory Actions

After World War II, Czechoslovakia was reestablished. Carpathian Ruthenia was occupied by and in June 1945 formally ceded to the Soviet Union, while ethnic Germans inhabiting the Sudetenland were expelled in an act of retaliation coined by the Beneš Decrees. Wartime traitors and collaborators accused of treason along with ethnic Germans and Hungarians were expropriated, with those ethnic Germans and Hungarians who switched to German and Hungarian citizenship during the occupation stripped of their national identity. These provisions were lifted for the Hungarians in 1948. Altogether around 90% of the ethnic German population of Czechoslovakia was made leave. Although the Decrees specified that the sanctions did not apply to anti-fascists, the decisionmaking was up to local municipalities. Some 250,000 Germans, many married to Czechs and anti-fascists, remained. The Beneš Decrees continue to fuel controversy between nationalist groups in the Czech Republic, Germany, Austria, and Hungary.[5].

Communist Takeover

The Communist takeover of Czechoslovakia was facilitated by the fact that most of the country had been liberated by the Red Army and by the overall social and economic downturn in Europe. Marshall’s Plan, authored by US State Secretary George Marshall in June 1947, addressed the needs of the war-bled Europe with an offer of financial and material aid that would stabilize the region but was turned down by the Soviet Union and, consequently, by its satellites, including Czechoslovakia. In the 1946 parliamentary election, the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia emerged as the winner in the Czech lands while the Democratic Party won in Slovakia, and in February 1948, the Communists seized power and sealed the country’s fate for the next 41 years. Terror reminiscent of Hitler’s Germany followed, with execution of political prisoners and prisoners of conscience, forceful collectivization of agriculture, censorship, and land grabs. Economy was controlled by five-year plans and the industry was overhauled in compliance with Soviet wishes to focus on heavy industry, in which Czechoslovakia had been traditionally weak. The economy retained momentum vis-à-vis its Eastern European neighbors but grew increasingly weak vis-à-vis Western Europe. Atheism became the official spiritual doctrine.

Year 1960 saw the declaration of the victory of socialism, with small businesses stamped out and the country’s name changed to the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. In early 60s, years of socialist planning brought about an economic crisis and reshuffles in the Communist leadership. Economic reforms were put in place and gradually grew into the reform of the overall political system. Slovakia’s Alexander Dubček spearheaded the doctrine of ‘socialism with human face’, called but the efforts during this period, referred to as the Prague Spring, were crushed under the tanks of the Warsaw Pact armies on August 21, 1968.

The Prague Spring gave in to the period of ‘normalization’, with political, military and union purges and the repeal of reforms, which thrust the country back into 1950s. The dissident movement, symbolized by the future Czech President Václav Havel, worked underground to counter the system and drew up Charter 77, a document that called for the enforcement of human rights. The government responded with a prohibition of professional employment for the dissidents, higher education for their children, police harassment, and prison time. All artists who wanted to continue working in their field were forced to sign the government-issued Anti-Charter.

In 1969, Czechoslovakia became a federation of the Czech Socialist Republic and Slovak Socialist Republic in a move to eliminate economic inequities between the two parts. A number of ministries were divided to cater to each part of the country; however, the centralized grip of the Communist Party diminished the effects of federalization.

In the 80s, the regime again grappled with a stifling economic crisis, and the revolutions in neighboring socialist countries encouraged Czechoslovakia to take steps toward democracy.

Velvet Revolution

1989 in the World

Mikhail Gorbachev’s address to the United Nations General Assembly in New York, in which he endorsed the rights for all nations to decide on their course, was among the first signs of the worldwide crumbling of the Communist empire. Gorbachev followed through with a unilateral withdrawal of 500,000 Soviet troops from Europe and Asia and rehabilitated victims of Stalin's rule. Elections in March 1989 saw Communist candidates defeated, and small Soviet republics were calling for secession from the Soviet Union. Hungary started taking steps toward democracy by allowing other than Communist political parties, but Communist authorities in Prague brutally dispersed ad hoc anti-regime demonstrations and Romania imprisoned journalists brave enough to criticize its President Ceausescu. Bloodbath occurred at East Berlin's infamous Berlin Wall. In Poland, a series of strikes forced the government to forge a deal with Lech Wałęsa, the leader of the Solidarita movement. One million students in Beijing took to the streets hoping that Gorbachev’s visit to China would bring about reforms; however, thousands of them were massacred at the Tchien-an-men Square.

November 1989

Prague planned demonstrations for November 17 in commemoration of the 1939 Nazi attack against university dormitories and the ensuing closure of universities for three years. That day in 1989, however, saw not only water hoses and spontaneous arrests but also sheer violence targeting young people, who were brutally beaten by the police that blocked off all escape routes at Prague's Nrodni Trida (National Avenue). This set in motion the Velvet Revolution, as the events in November and December that unseated Communism in the country came to be known—the Communist Party was forced to rescind its leading role. The main force behind the revolution was Prague students, who solicited support of artists and actors. Protests in the metropolis soon spilled over to other parts of the country, and in the second half of November, Slovak artists, scientists and prominent figures set up the Public Against Violence movement in Slovakia, which would become the vehicle for the opposition movement there, with actor Milan Kňažko and Ján Budaj among the key figures. In the Czech lands, Václav Havel, playwright and dissident, and other outspoken members of Charter 77 and dissident organizations established the Civic Forum.

As Communist governments in neighboring countries were being toppled, the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia announced in late November an intention to hand over power. Borders with Western Europe were open in early December, and a week later, President Gustáv Husák appointed the first government composed of largely non-Communists since 1948, and resigned. Alexander Dubček, who played a crucial role in the Prague Spring, became the voice of the federal parliament and Václav Havel the President. In June 1990, the first democratic elections since 1946 were held.

Toward Velvet Divorce

Discussion of the proposal to drop the country’s socialist attribute introduced in 1960 revealed a serious Czecho-Slovak conflict, with many Slovak deputies calling for the reinstatement of the original name, Czecho-Slovakia, adopted by the Treaty of Versailles in 1918. The country was eventually renamed the Czech and Slovak Federal Republic in April 1990, but voices for Slovakia’s indepence were mounting, and the fiercely nationalistic Slovak National Party, whose key agenda was independence, was founded around this time. Even prior to that, Slovakia's creation of the Foreign Relations Ministry in 1990 had signaled intensified independence efforts.

The June 1990 elections uncovered the growing rift between the two countries when Slovakia openly challenged President Havel's intervening in Slovak internal affairs. While the conservative Civic Democratic Party (ODS) won a sweeping victory in the Czech Republic, Slovakia voted in the liberal Movement for a Democratic Slovakia (HZDS). The cabinets of both countries were no longer composed of mostly former dissidents, and although the federal government operated on the principle of symmetric power-sharing, disagreements between the republics escalated into Slovakia’s declaration of a sovereign state in July 1992, whereby its laws overrode the federal laws. Negotiations on the dissolution of the federal state took place for the rest of the year, which was materialized on January 1, 1993, when two independent states—Slovakia and the Czech Republic—appeared on the map of Europe.

From Creation to Dissolution — Overview

|

Czechoslovakia (or Czecho-Slovakia) | 1918 - 1939; 1945 - 1992 |

|||||||

|

Austria-Hungary (Bohemia, Moravia, a part of Silesia, northern parts of the Kingdom of Hungary (Slovakia and Carpathian Ruthenia) |

Czechoslovak Republic |

Sudetenland + other German territories "Upper Hungary" territories of Hungary |

Czechoslovak Republic (ČSR) |

Czechoslovak Socialist Republic (ČSSR) |

Czech and Slovak Federal Republic (ČSFR) |

Czech Republic Slovakia |

|

|

Czecho-Slovak Republic (ČSR) incl. autonomous Slovakia and Transcarpathian Ukraine (1938-1939) |

Protectorate WWII Slovak Republic |

||||||

|

(further) "Upper Hungary" of Hungary |

part of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic |

Zakarpattia Oblast of Ukraine |

|||||

|

German occupation |

Communist era |

||||||

|

govern. in exile |

|||||||

Footnotes

- ↑ July 6, 2005, "Playing the Blame Game", Prague Post[1]

- ↑ March 15, 2007, "Chcete zničit Prahu? ptal se Göring Háchy", idnes News [2]

- ↑ March 15, 2007, "Chcete zničit Prahu? ptal se Göring Háchy", idnes News [3]

- ↑ "Munich Agreement", Wikipedia [4]

- ↑ "The Other Central Europe", The New York University School of Law [5]

External Links

English Language

- Czechoslovak Republicdefunct link, Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- "Munich Agreement" Wikipedia, Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- "Velvet Revolution"] Wikipedia, Retrieved June 14, 2007.

- "The Breakup of Czechoslovakia" Slovakia Website, Retrieved July 4, 2007.

Czech Language

- “Czechoslovak Orders and Medals” Awards, Retrieved June 10, 2007.

- “Lidice a Ležáky“ Czech Republic History, Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- Gazdik, Jan March 15, 2007 ”Do You Want to Destroy Prague? Goring Asked Hacha” iDnes News, Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- “Czechoslovak Resistance Movement in the West” Wars, Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- “Emergence of Czechoslovakia and Shaping of our Borders” Jan Skokan’s History Website, Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- Mikulecky, Tomas “Emergence of Czechoslovakia” Resources for Students, Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- “Second Czechoslovak Resistance Movement” Resources for Students, Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- “Second Czechoslovak Resistance Movement, the Role of the Three Kings and the Resistance Movement Role of Vladimir Krajina” History, Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- ”Life in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia” Resources for Students, Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- “Assassination of Reynhard Heidrich” Resources for Students, Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- “Velvet Revolution or Eleven Days that Rocked Czechoslovakia” Totalitarianism, Retrieved June 4, 2007.* “International Events of 1989” Totalitarianism, Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- “Political Processes in the Czech Socialist Republic 1948-1989” Resources for Students, Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- “Timeline of November 17 Demonstrations” Totalitarianism, Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- “Charter 77” Resources for Students, Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- “Velvet Revolution ‘89” 1989 Revolution, Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- "History of the Ministry" Czech Republic Finance Ministry, Retrieved July 4, 2007.

- "January 1993: Breakup of Czechoslovakia and Creation of Independent Czech Diplomacy" Czech Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Retrieved July 4, 2007.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.