Difference between revisions of "Czechoslovakia" - New World Encyclopedia

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (44 intermediate revisions by 9 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Copyedited}}{{Approved}}{{Submitted}}{{Images OK}}{{Paid}} |

{{Infobox Former Country | {{Infobox Former Country | ||

|native_name = Československo | |native_name = Československo | ||

|conventional_long_name = Czechoslovakia | |conventional_long_name = Czechoslovakia | ||

| − | |common_name | + | |common_name = Czechoslovakia |

|continent = Europe | |continent = Europe | ||

|government_type = Republic | |government_type = Republic | ||

| − | |year_start | + | |year_start = 1918 |

|event_start = Independence from Austria-Hungary | |event_start = Independence from Austria-Hungary | ||

| − | |date_start | + | |date_start = 28 October |

| − | |year_end | + | |year_end = 1992 |

| − | |event_end | + | |event_end = [[Dissolution of Czechoslovakia]] |

| − | |date_end | + | |date_end = 31 December |

| − | |p1 | + | |p1 = Austria-Hungary |

| − | |flag_p1 | + | |flag_p1 = Austria-Hungary flag 1869-1918.svg |

| − | |s1 | + | |s1 = Czech Republic |

| − | |flag_s1 | + | |flag_s1 = Flag of the Czech Republic (bordered).svg |

| − | |s2 | + | |s2 = Slovakia |

| − | |flag_s2 | + | |flag_s2 = Flag of Slovakia (bordered).svg |

| − | |image_flag | + | |image_flag = Flag of Czechoslovakia.svg |

| − | |flag | + | |flag = Flag of Czechoslovakia |

|flag_border = Flag of Czechoslovakia | |flag_border = Flag of Czechoslovakia | ||

| − | |image_coat | + | |image_coat = 499px-CoA CSFRc svg.png |

| − | |symbol | + | |symbol = Coat of arms of Czechoslovakia |

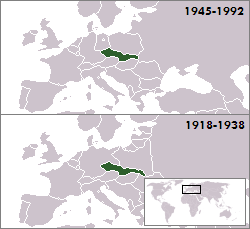

| − | |image_map | + | |image_map = LocationCzechoslovakia.png |

| − | |capital | + | |capital = Prague |

|latd=50|latm=05|latNS=N|longd=14|longm=28|longEW=E| | |latd=50|latm=05|latNS=N|longd=14|longm=28|longEW=E| | ||

| − | |national_motto | + | |national_motto = [[Czech language|Czech]]: ''Pravda vítězí''<br/>("Truth prevails"; 1918-1989)<br/>[[Latin]]: ''Veritas Vincit''<br/>("Truth prevails"; 1989-1992) |

| − | |national_anthem | + | |national_anthem = ''[[Kde domov můj]]'' and ''[[Nad Tatrou sa blýska]]'' |

|common_languages = [[Czech language|Czech]], [[Slovak language|Slovak]] | |common_languages = [[Czech language|Czech]], [[Slovak language|Slovak]] | ||

| − | |currency | + | |currency = [[Czechoslovak crown]] |

| − | |leader1 | + | |leader1 = Tomáš Masaryk |

| − | |leader2 | + | |leader2 = Václav Havel |

|year_leader1 = 1918-1935 | |year_leader1 = 1918-1935 | ||

|year_leader2 = 1989-1992 | |year_leader2 = 1989-1992 | ||

| − | |leader | + | |leader = |

|title_leader = [[List of Presidents of Czechoslovakia|President]] | |title_leader = [[List of Presidents of Czechoslovakia|President]] | ||

| − | |deputy1 | + | |deputy1 = Karel Kramář |

| − | |deputy2 | + | |deputy2 = Jan Stráský |

|year_deputy1 = 1918-1919 | |year_deputy1 = 1918-1919 | ||

|year_deputy2 = 1992 | |year_deputy2 = 1992 | ||

| Line 43: | Line 43: | ||

|stat_year1 = 1993 | |stat_year1 = 1993 | ||

|stat_area1 = 127900 | |stat_area1 = 127900 | ||

| − | |stat_pop1 | + | |stat_pop1 = 15600000 |

}} | }} | ||

| − | + | '''Czechoslovakia''' ([[Czech language|Czech]] and [[Slovak language|Slovak]] languages: ''Československo'') was a country in [[Central Europe]] that existed from October 28, 1918, when it declared independence from the [[Austro-Hungarian Empire]], until 1992. On January 1, 1993, [[Dissolution of Czechoslovakia|Czechoslovakia split]] into the '''[[Czech Republic]]''' and '''[[Slovakia]]'''. During the 74 years of its existence, it saw several changes in the political and economic climate. It consisted of two predominant ethnic Slavic groups—Czechs and Slovaks—with Slovakia's population half the Czech Republic's. During [[World War II]], Slovakia declared independence as an ally of the [[fascism|Nazi]] [[Germany]], while the Czech lands were handed over to [[Adolf Hitler|Hitler]] by the [[Allies]] in an act of appeasement. Czechoslovakia fell under the [[Soviet Union|Soviet]] sphere of influence following liberation largely by the Soviet Union's Red Army. It rejected the [[Marshall Plan]], joined the [[Warsaw Pact]], nationalized private businesses and property, and introduced central economic planning. The [[Cold War]] period was interrupted by the economic and political reforms of the [[Prague Spring]] in 1968. | |

| − | '''Czechoslovakia''' ([[Czech language|Czech]] and [[Slovak language|Slovak]]: ''Československo | + | {{toc}} |

| − | + | In November 1989, Czechoslovakia joined the wave of anti-Communist uprisings throughout the [[Eastern bloc]] and embraced [[democracy]]. Addressing the Communist legacy, both in political and economic terms, was a painful process accompanied by escalated [[nationalism]] in Slovakia and its mounting sense of unfair economic treatment by the Czechs, which resulted in a peaceful split labeled the ''Velvet Divorce''. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

== Basic Facts== | == Basic Facts== | ||

| Line 58: | Line 53: | ||

'''Form of statehood''': | '''Form of statehood''': | ||

* 1918–1938: [[democracy|democratic]] republic | * 1918–1938: [[democracy|democratic]] republic | ||

| − | * 1938–1939: after annexation of the Sudetenland region by [[Germany]] in 1938, Czechoslovakia turned into a state with loosened connections between its Czech, [[Slovakia|Slovak]] and Ruthenian parts. A large strip of southern Slovakia and Ruthenia was annexed by [[Hungary]], while the Zaolzie region | + | * 1938–1939: after annexation of the Sudetenland region by [[Germany]] in 1938, Czechoslovakia turned into a state with loosened connections between its Czech, [[Slovakia|Slovak]] and Ruthenian parts. A large strip of southern Slovakia and Ruthenia was annexed by [[Hungary]], while the Zaolzie region fell under [[Poland]]'s control |

| − | * 1939–1945: split into the Protectorate of [[Bohemia]] and Moravia and the independent [[Slovakia]], although Czechoslovakia was never officially dissolved; its exiled government, recognized by the Western Allies, was based in [[London]] | + | * 1939–1945: split into the Protectorate of [[Bohemia]] and [[Moravia]] and the independent [[Slovakia]], although Czechoslovakia per se was never officially dissolved; its exiled government, recognized by the Western Allies, was based in [[London]]. |

* 1945–1948: democracy, governed by a coalition government, with [[Communism|Communist]] ministers charting the course | * 1945–1948: democracy, governed by a coalition government, with [[Communism|Communist]] ministers charting the course | ||

* 1948–1989: Communist state with a centrally planned economy | * 1948–1989: Communist state with a centrally planned economy | ||

** 1960 on: the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic | ** 1960 on: the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic | ||

| − | ** 1969–1990: | + | ** 1969–1990: federal republic consisting of the ''Czech Socialist Republic'' and the ''Slovak Socialist Republic'' |

* 1990–1992: a federal democratic republic consisting of the ''Czech Republic'' and the ''Slovak Republic'' | * 1990–1992: a federal democratic republic consisting of the ''Czech Republic'' and the ''Slovak Republic'' | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

== History == | == History == | ||

| + | {{readout||left|250px|Czechoslovakia was a country in Central Europe that existed from October 28, 1918, when it declared independence from the [[Austro-Hungarian Empire]], until January 1, 1993, when it split into the [[Czech Republic]] and [[Slovakia]]}} | ||

| + | ===Inception of Czechoslovakia=== | ||

| − | [[ | + | Czechoslovakia came into existence in October 1918 as one of the successor states of [[Austria-Hungary]], whose Empire had been slowly losing ground to [[Nationalism|nationalist]] movements in the final years of [[World War I]]. It was comprised of the territories of the [[Czech Republic]], [[Slovakia]], and Carpathian Ruthenia and some of the most industrialized regions of the former Austria-Hungary. On October 28, 1918, Alois Rašín, Antonín Švehla, František Soukup, Jiří Stříbrný, and Vavro Šrobár, the "Men of October 28th," formed a provisional government, and two days later, Slovakia endorsed the marriage of the two countries, with [[Tomas Garrigue Masaryk]], who had crafted the blueprint for the constitution, elected president. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | === | + | ==World War II== |

| − | + | [[Image:Czechoslovakia01.png|thumb|275px|Czechoslovakia in 1928]] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[Image:Czechoslovakia01.png|thumb| | ||

| − | |||

===End of State=== | ===End of State=== | ||

| + | Satisfaction among individual ethnic groups within the new state varied, as Germans, Slovaks, and Slovakia's ethnic Hungarians grew resentful of the political and economic dominance of the Czechs' reluctance to extend political autonomy to all constituents. This policy, combined with an increasing [[Nazism|Nazi]] propaganda, particularly in the industrialized German speaking [[Sudetenland]] (the German-border regions of Bohemia and Moravia), fueled the growing unrest in the years leading up to [[World War II]].<ref> Peter Josika, [http://www.praguepost.com/articles/2005/07/06/playing-the-blame-game.php Playing the Blame Game], ''Prague Post'' (July 6, 2005). Retrieved September 5, 2007. </ref> Czechoslovakia began losing ground to [[Adolf Hitler]]'s Germany with the [[Munich Agreement]], signed on September 29, 1938, by the representatives of Germany—Hitler, [[Great Britain]]—[[Neville Chamberlain]], [[Italy]]—[[Benito Mussolini]], and [[France]]—[[Édouard Daladier]], which deprived it of one-third of its territory, mainly the Sudetenland, the location of major border defenses. Within ten days, 1,200,000 were forced to leave their homes. President Edvard Beneš resigned on October 5, 1938, and [[Emil Hácha]] was appointed in his stead. Hitler thus defeated Czechoslovakia without taking up arms, while a strip of southern [[Slovakia]] was handed over to [[Hungary]] in November. | ||

| − | + | On March 14, 1939, Hácha set out for [[Berlin]] to meet with Hitler. On the same day, Slovakia declared independence and became an ally of Nazi Germany, which provided Hitler with a pretext to occupy Bohemia and Moravia on grounds that Czechoslovakia had collapsed from within and his administration of it would forestall chaos in Central [[Europe]]. Hácha described the signing away of Czechoslovakia as follows: <blockquote>“It’s possible to withstand Hitler’s yelling, because a person who yells is not necessarily a devil. But Göring [Hitler’s right hand], with his jovial face, was there as well. He took me by the hand and softly reproached me, asking whether it is really necessary for the beautiful [[Prague]] to be leveled in a few hours… and I could tell that the devil, able to carry out his threat, was speaking to me.”<ref> ''idnes News'', [http://zpravy.idnes.cz/chcete-znicit-prahu-ptal-se-goring-hachy-f0x-/domaci.asp?c=A070315_093114_domaci_adb Chcete zničit Prahu? ptal se Göring Háchy], March 15, 2007. (Czech Language) Retrieved September 5, 2007. </ref></blockquote> | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | The following morning, [[Wehrmacht]] occupied what remained of Czechoslovakia. After Hitler personally inspected the Czech fortifications, he privately admitted that “We would have shed a lot of blood.” | |

| − | |||

| − | On March 14, 1939, Hácha set out for Berlin to meet with Hitler | ||

| − | |||

| − | The | ||

Slovakia's troops fought on the Russian front until the summer of 1944, when the Slovak armed forces staged an anti-government uprising that was quickly crushed by Germany. | Slovakia's troops fought on the Russian front until the summer of 1944, when the Slovak armed forces staged an anti-government uprising that was quickly crushed by Germany. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

===Resistance Movement=== | ===Resistance Movement=== | ||

| − | + | On October 28, 1939, the 21st anniversary of the establishment of the country, Czechoslovakia, emboldened by hopes for an early restoration of the independence, was swept by massive demonstrations. Nazi Germany retaliated by spontaneous executions of student leaders and the closure of universities, which sent the resistance movement underground. Czechoslovak units composed of recruits from the ranks of exiled Czechoslovak citizens were created in [[Poland]], [[France]], and [[Great Britain]], coordinated by the London-based exiled government. On the home turf, the resistance movement continued chiefly through massive demonstrations, which reached an apex in 1941. However, widespread arrests severely disrupted the underground networks and cut off radio networks between domestic and foreign components of the resistance movement, which were then reestablished by paratroopers dispatched into the Protectorate. | |

| − | On October 28, 1939, the 21st anniversary of the establishment of the country, Czechoslovakia, emboldened by hopes for an early restoration of the independence, was swept by massive demonstrations. | ||

| − | |||

| − | On the home turf, resistance movement continued chiefly through massive demonstrations, which reached an apex in 1941 | ||

===Operation Anthropoid=== | ===Operation Anthropoid=== | ||

| + | [[Image:Peace park memorial.jpg|right|thumb|275px|"Joy of Life" statue gifted to the Nagasaki Peace Park by Czechoslovakia in 1980.]] | ||

| + | The Czechoslovak-British Operation Anthropoid was the code name for the assassination plot of the top Nazi leader [[Reinhard Heydrich]], the chief of RSHA, an organization that included the [[Gestapo]] (Secret Police), SD (Security Agency) and Kripo (Criminal Police). Heydrich was the mastermind of the purge of Hitler's opponents as well as the [[genocide]] of [[Jews]]. Due to his reputation as the liquidator of resistance movements in [[Europe]], he was sent to [[Prague]] in September 1941 to make order as the Protector of Bohemia and Moravia. The Protectorate was of strategic importance to Hitler’s plans, and Heydrich, dubbed the "Butcher of Prague," "The Blond Beast" or "The Hangman," wasted no time, handing out death sentences the day after his arrival. | ||

| − | + | With the fighting spirit in the Protectorate at a lull, the exiled military officials began planning an operation that would stir up the nation’s consciousness—six Czech and one Slovak paratroopers were chosen for the assassination of Heydrich, and two of them—Czech Josef Valčík and Slovak Josef Gabčik, executed it. Heydrich died of complications following surgery. The Gestapo tracked the paratroopers’ contacts and eventually discovered the assassins' hideaway in a Prague church. Three of them died in a shootout while trying to buy time for the others who were attempting to dig an escape route; the remaining four used their last bullets to take their lives. | |

| − | |||

| − | With the fighting spirit in the Protectorate at lull, the exiled military officials | ||

| − | Heydrich’s successor Karl Herrmann Frank had 10,000 Czechs executed as a warning, and two villages that assisted the paratroopers were leveled | + | Heydrich’s successor [[Karl Herrmann Frank]] had 10,000 Czechs executed as a warning, and two villages that assisted the paratroopers were leveled, with the adults murdered and young children sent to German families for re-education. The combined actions of the Gestapo and its confidantes virtually paralyzed the Czech resistance movement; on the other hand, the assassination bolstered Czechoslovakia’s prestige in the world and was crucial to the country’s securing of demands for an independent republic following the end of [[WWII]]. |

===End of War=== | ===End of War=== | ||

| − | Toward the end of the war, partisan movement was gaining momentum, and once the Allies were on the winning side, the political orientation of Czechoslovakia was high on the agenda of the two most influential exiled | + | Toward the end of the war, partisan movement was gaining momentum, and once the Allies were on the winning side, the political orientation of Czechoslovakia was high on the agenda of the two most influential exiled centers—the government in [[London]] and the [[communism|communist]] officials in [[Moscow]]. Both endorsed the agreement on friendship, mutual assistance and postwar cooperation with the [[Soviet Union]] as a means to stem German expansion on one hand and the Soviet Union’s mingling into Czechoslovakia's internal affairs on the other. |

==Communist Czechoslovakia== | ==Communist Czechoslovakia== | ||

| − | |||

| − | After World War II, Czechoslovakia was reestablished. Carpathian Ruthenia | + | ===Retaliation=== |

| + | After [[World War II]], Czechoslovakia was reestablished. Carpathian Ruthenia was occupied by, and in June 1945, formally ceded to the [[Soviet Union]], while Sudetenland Germans were expelled in an act of retaliation coined by the Beneš Decrees, which continue to fuel controversy between nationalist groups in the [[Czech Republic]], [[Germany]], [[Austria]], and [[Hungary]].<ref> Jacques Rupnik, [http://www.law.nyu.edu/eecr/vol11num1_2/special/rupnik.html The Other Central Europe], ''East European Constitutional Review'' (Winter/Spring 2002). Retrieved September 5, 2007. </ref> In total approximately 90 percent of the ethnic German population of Czechoslovakia was forced to leave. Wartime traitors and collaborators accused of [[treason]] along with ethnic Germans and Hungarians were expropriated. | ||

| − | The Communist takeover of Czechoslovakia was facilitated by the | + | === Communist Takeover=== |

| − | The economy retained momentum vis-à-vis its Eastern | + | The Communist takeover of Czechoslovakia was facilitated by the fact that most of the country had been liberated by the [[Red Army]], as well as the overall social and economic downturn in [[Europe]]. In the 1946 parliamentary election, the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia emerged as the winner in the Czech lands while the Democratic Party won in Slovakia. In 1947, the Soviet Union and, consequently, its satellites, including Czechoslovakia, turned down the [[Marshall Plan]], authored by [[U.S.]] Secretary of State [[George Marshall]] to address the economic needs of war-torn Europe. |

| − | + | [[Image:Czechoslovakia.png|thumb|left|275px|Czechoslovakia in 1969]] | |

| − | + | In February 1948, the Communists seized power and sealed the country’s fate for the next 41 years. Terror reminiscent of Hitler’s Germany followed, with execution of political prisoners and prisoners of conscience, forced collectivization of [[agriculture]], [[censorship]], and land grabs. Economy was controlled by five-year plans and the industry was overhauled in compliance with Soviet wishes to focus on heavy industry, in which Czechoslovakia had been traditionally weak. The economy retained momentum vis-à-vis its [[Eastern Europe]]an neighbors but grew increasingly weak vis-à-vis [[Western Europe]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | In the early 1960s, Czechoslovakia came very close to extricating itself from the Eastern bloc, when the reformer [[Alexander Dubcek]] was appointed to the key post of First Secretary of the Czechoslovak Communist Party. Economic reforms were put in place that gradually grew into the reform of the overall political system, referred to as the [[Prague Spring]]. However, this glimmer of hope was crushed under the tanks of the [[Warsaw Pact]] armies in August 1968. Soviet tanks rolled into Czechoslovakia on the night of 20–21 August 1968.<ref>[http://www.upi.com/Audio/Year_in_Review/Events-of-1968/N.-Korea-Seize-U.S.-Ship/12303153093431-9/#title "Russia Invades Czechoslovakia: 1968 Year in Review,"] UPI.com (1968). Retrieved November 23, 2011.</ref> The General Secretary of the Soviet Communist Party [[Leonid Brezhnev]] viewed this intervention as vital to the preservation of the Soviet, socialist system and vowed to intervene in any state that sought to replace [[Marxism]]-[[Leninism]] with [[capitalism]].<ref>John Lewis Gaddis, ''The Cold War: A New History'' (New York, NY: The Penguin Press, 2006), 150.</ref> In the week after the invasion there was a spontaneous campaign of [[civil resistance]] against the occupation. This resistance involved a wide range of acts of non-cooperation and defiance: this was followed by a period in which the Czechoslovak Communist Party leadership, having been forced in Moscow to make concessions to the Soviet Union, gradually put the brakes on their earlier liberal policies.<ref>Philip Windsor and Adam Roberts, ''Czechoslovakia 1968: Reform, Repression and Resistance'' (London: Chatto & Windus, 1969), 97-143.</ref> In April 1969 Dubcek was finally dismissed from the First Secretaryship of the Czechoslovak Communist Party. | ||

| + | The period of ‘normalization’ followed—the reforms were repealed, which, compounded by apolitical, military, and union purges thrust the country back into 1950s. The dissident movement, epitomized by the future Czech President [[Václav Havel]], worked underground to counter the regime. Finally, the economic crisis in the 1980s facilitated the shift toward [[democracy]]. | ||

==Velvet Revolution== | ==Velvet Revolution== | ||

| + | [[Mikhail Gorbachev|Mikhail Gorbachev’s]] address to the [[United Nations]] General Assembly in [[New York]], in which he endorsed the rights for all nations to decide their own course, was among the first signs of the worldwide crumbling of the Communist empire. However, Communist authorities in [[Prague]] brutally dispersed ad hoc anti-regime demonstrations on November 17, 1989, in commemoration of the 1939 Nazi attack against university dormitories. This set in motion the [[Velvet Revolution]], and the student-led protests in the metropolis soon spilled over to other parts of the country. | ||

| − | + | As Communist governments in neighboring countries were being toppled, borders with [[Western Europe]] were opened, and in December, President Gustáv Husák appointed the first government composed of largely non-Communists and resigned. [[Alexander Dubcek]], who played a crucial role in the [[Prague Spring]], became the voice of the federal parliament and [[Vaclav Havel]] the President. In June 1990, the first democratic elections since 1946 were held. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | As Communist governments in neighboring countries were being toppled, | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Toward Velvet Divorce== | ==Toward Velvet Divorce== | ||

| + | Discussion of the proposal to drop the country’s [[socialism|socialist]] attribute introduced in 1960 revealed a serious Czecho-Slovak conflict, with many Slovak deputies calling for the reinstatement of the original name, "Czecho-Slovakia," adopted by the [[Treaty of Versailles]] in 1918. The country was eventually renamed the Czech and Slovak Federal Republic in April 1990, but voices for Slovakia’s independence were mounting, and the fiercely [[nationalism|nationalistic]] Slovak National Party, whose key agenda was independence, was founded around this time. Even prior to that, Slovakia's creation of the Foreign Relations Ministry in 1990 had signaled intensified independence efforts. | ||

| − | + | The June 1990 elections uncovered the growing rift between the two countries when [[Slovakia]] openly challenged President Havel's intervening in Slovak internal affairs. While the conservatives won a sweeping victory in the [[Czech Republic]], Slovakia elected liberals. The cabinets of both countries were no longer largely composed of former dissidents, and although the federal government operated on the principle of symmetric power-sharing, disagreements between the republics escalated into Slovakia’s declaration of a sovereign state in July 1992, whereby its laws overrode the federal laws. Negotiations on the dissolution of the federal state took place for the remainder of the year, which was materialized on January 1, 1993, when two independent states—Slovakia and the Czech Republic—appeared on the map of [[Europe]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | The June 1990 elections uncovered the growing rift between the two countries when Slovakia openly challenged President Havel's intervening in Slovak internal affairs. While the | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == | + | == See also == |

| − | + | * [[Alexander Dubcek]] | |

| + | * [[Czech Republic]] | ||

| + | * [[Prague Spring]] | ||

| + | * [[Slovakia]] | ||

| + | * [[Vaclav Havel]] | ||

| + | * [[Velvet Revolution]] | ||

| + | * [[Dissolution of Czechoslovakia]] | ||

| − | == | + | == Notes== |

<references/> | <references/> | ||

| + | ==References== | ||

| + | *Gaddis, John Lewis. ''The Cold War: A New History''. New York, NY: The Penguin Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0143038276 | ||

| + | *Heimann, Mary. ''Czechoslovakia: The State That Failed''. Yale University Press, 2011. ISBN 978-0300172423 | ||

| + | *Windsor, Philip, and Adam Roberts. ''Czechoslovakia 1968: Reform, Repression and Resistance''. London: Chatto & Windus, 1969. {{ASIN|B01K1756RS}} | ||

==External Links== | ==External Links== | ||

| − | + | All links retrieved January 12, 2024. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

===Czech Language=== | ===Czech Language=== | ||

| − | + | * Gazdik, Jan. March 15, 2007. [http://zpravy.idnes.cz/chcete-znicit-prahu-ptal-se-goring-hachy-f0x-/domaci.asp?c=A070315_093114_domaci_adb ”Do You Want to Destroy Prague? Goring Asked Hacha”] ''iDnes News'' | |

| − | + | * [http://hartmann.valka.cz/udalostiww2/czwestcp/index.htm “Czechoslovak Resistance Movement in the West”] ''Wars'' | |

| − | * Gazdik, Jan March 15, 2007 [http://zpravy.idnes.cz/chcete-znicit-prahu-ptal-se-goring-hachy-f0x-/domaci.asp?c=A070315_093114_domaci_adb ”Do You Want to Destroy Prague? Goring Asked Hacha”] ''iDnes News'' | + | * Mikulecky, Tomas. [http://referaty.cz/referaty/referat.asp?id=5986 “Emergence of Czechoslovakia”] ''Resources for Students'' |

| − | * [http://hartmann.valka.cz/udalostiww2/czwestcp/index.htm “Czechoslovak Resistance Movement in the West”] ''Wars'' | + | * [http://www.maturita.cz/referaty/referat.asp?id=4702 “Second Czechoslovak Resistance Movement”] ''Resources for Students'' |

| − | + | * [http://dejepis.info/?t=190 “Second Czechoslovak Resistance Movement, the Role of the ''Three Kings'' and the Resistance Movement Role of Vladimir Krajina”] ''History''. | |

| − | * Mikulecky, Tomas [http://referaty.cz/referaty/referat.asp?id=5986 “Emergence of Czechoslovakia”] ''Resources for Students'' | + | * [http://referaty.cz/referaty/referat.asp?id=2721 ”Life in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia”] ''Resources for Students'' |

| − | * [http://www.maturita.cz/referaty/referat.asp?id=4702 “Second Czechoslovak Resistance Movement”] ''Resources for Students'' | + | * [http://referaty.cz/referaty/referat.asp?id=5271 “Assassination of Reynhard Heidrich”] ''Resources for Students'' |

| − | * [http://dejepis.info/?t=190 “Second Czechoslovak Resistance Movement, the Role of the ''Three Kings'' and the Resistance Movement Role of Vladimir Krajina”] ''History'' | + | * [http://www.totalita.cz/1989/1989_11.php “Velvet Revolution or Eleven Days that Rocked Czechoslovakia”] ''Totalitarianism'' |

| − | * [http://referaty.cz/referaty/referat.asp?id=2721 ”Life in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia”] ''Resources for Students'' | + | * [http://www.totalita.cz/1989/1989_ms.php “International Events of 1989”] ''Totalitarianism'' |

| − | * [http://referaty.cz/referaty/referat.asp?id=5271 “Assassination of Reynhard Heidrich”] ''Resources for Students'' | + | * [http://referaty.cz/referaty/referat.asp?id=7664 “Political Processes in the Czech Socialist Republic 1948-1989”] ''Resources for Students'' |

| − | * [http://www.totalita.cz/1989/1989_11.php “Velvet Revolution or Eleven Days that Rocked Czechoslovakia”] ''Totalitarianism'' | + | * [http://www.totalita.cz/1989/1989_1117_dem_01.php “Timeline of November 17 Demonstrations”] ''Totalitarianism'' |

| − | * [http://referaty.cz/referaty/referat.asp?id=7664 “Political Processes in the Czech Socialist Republic 1948-1989”] ''Resources for Students'' | + | * [http://referaty.cz/referaty/referat.asp?id=4961 “Charter 77”] ''Resources for Students'' |

| − | * [http://www.totalita.cz/1989/1989_1117_dem_01.php “Timeline of November 17 Demonstrations”] ''Totalitarianism'' | ||

| − | * [http://referaty.cz/referaty/referat.asp?id=4961 “Charter 77”] ''Resources for Students'' | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | {{credit|Czechoslovakia|104011362|Munich_Agreement|154918103|Velvet_Revolution|153508749}} | |

| − | |||

| − | + | [[Category:Geography]] | |

| − | + | [[Category:Former Countries]] | |

Latest revision as of 07:31, 12 January 2024

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Czechoslovakia (Czech and Slovak languages: Československo) was a country in Central Europe that existed from October 28, 1918, when it declared independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, until 1992. On January 1, 1993, Czechoslovakia split into the Czech Republic and Slovakia. During the 74 years of its existence, it saw several changes in the political and economic climate. It consisted of two predominant ethnic Slavic groups—Czechs and Slovaks—with Slovakia's population half the Czech Republic's. During World War II, Slovakia declared independence as an ally of the Nazi Germany, while the Czech lands were handed over to Hitler by the Allies in an act of appeasement. Czechoslovakia fell under the Soviet sphere of influence following liberation largely by the Soviet Union's Red Army. It rejected the Marshall Plan, joined the Warsaw Pact, nationalized private businesses and property, and introduced central economic planning. The Cold War period was interrupted by the economic and political reforms of the Prague Spring in 1968.

In November 1989, Czechoslovakia joined the wave of anti-Communist uprisings throughout the Eastern bloc and embraced democracy. Addressing the Communist legacy, both in political and economic terms, was a painful process accompanied by escalated nationalism in Slovakia and its mounting sense of unfair economic treatment by the Czechs, which resulted in a peaceful split labeled the Velvet Divorce.

Basic Facts

Form of statehood:

- 1918–1938: democratic republic

- 1938–1939: after annexation of the Sudetenland region by Germany in 1938, Czechoslovakia turned into a state with loosened connections between its Czech, Slovak and Ruthenian parts. A large strip of southern Slovakia and Ruthenia was annexed by Hungary, while the Zaolzie region fell under Poland's control

- 1939–1945: split into the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia and the independent Slovakia, although Czechoslovakia per se was never officially dissolved; its exiled government, recognized by the Western Allies, was based in London.

- 1945–1948: democracy, governed by a coalition government, with Communist ministers charting the course

- 1948–1989: Communist state with a centrally planned economy

- 1960 on: the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic

- 1969–1990: federal republic consisting of the Czech Socialist Republic and the Slovak Socialist Republic

- 1990–1992: a federal democratic republic consisting of the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic

History

Inception of Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia came into existence in October 1918 as one of the successor states of Austria-Hungary, whose Empire had been slowly losing ground to nationalist movements in the final years of World War I. It was comprised of the territories of the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Carpathian Ruthenia and some of the most industrialized regions of the former Austria-Hungary. On October 28, 1918, Alois Rašín, Antonín Švehla, František Soukup, Jiří Stříbrný, and Vavro Šrobár, the "Men of October 28th," formed a provisional government, and two days later, Slovakia endorsed the marriage of the two countries, with Tomas Garrigue Masaryk, who had crafted the blueprint for the constitution, elected president.

World War II

End of State

Satisfaction among individual ethnic groups within the new state varied, as Germans, Slovaks, and Slovakia's ethnic Hungarians grew resentful of the political and economic dominance of the Czechs' reluctance to extend political autonomy to all constituents. This policy, combined with an increasing Nazi propaganda, particularly in the industrialized German speaking Sudetenland (the German-border regions of Bohemia and Moravia), fueled the growing unrest in the years leading up to World War II.[1] Czechoslovakia began losing ground to Adolf Hitler's Germany with the Munich Agreement, signed on September 29, 1938, by the representatives of Germany—Hitler, Great Britain—Neville Chamberlain, Italy—Benito Mussolini, and France—Édouard Daladier, which deprived it of one-third of its territory, mainly the Sudetenland, the location of major border defenses. Within ten days, 1,200,000 were forced to leave their homes. President Edvard Beneš resigned on October 5, 1938, and Emil Hácha was appointed in his stead. Hitler thus defeated Czechoslovakia without taking up arms, while a strip of southern Slovakia was handed over to Hungary in November.

On March 14, 1939, Hácha set out for Berlin to meet with Hitler. On the same day, Slovakia declared independence and became an ally of Nazi Germany, which provided Hitler with a pretext to occupy Bohemia and Moravia on grounds that Czechoslovakia had collapsed from within and his administration of it would forestall chaos in Central Europe. Hácha described the signing away of Czechoslovakia as follows:

“It’s possible to withstand Hitler’s yelling, because a person who yells is not necessarily a devil. But Göring [Hitler’s right hand], with his jovial face, was there as well. He took me by the hand and softly reproached me, asking whether it is really necessary for the beautiful Prague to be leveled in a few hours… and I could tell that the devil, able to carry out his threat, was speaking to me.”[2]

The following morning, Wehrmacht occupied what remained of Czechoslovakia. After Hitler personally inspected the Czech fortifications, he privately admitted that “We would have shed a lot of blood.”

Slovakia's troops fought on the Russian front until the summer of 1944, when the Slovak armed forces staged an anti-government uprising that was quickly crushed by Germany.

Resistance Movement

On October 28, 1939, the 21st anniversary of the establishment of the country, Czechoslovakia, emboldened by hopes for an early restoration of the independence, was swept by massive demonstrations. Nazi Germany retaliated by spontaneous executions of student leaders and the closure of universities, which sent the resistance movement underground. Czechoslovak units composed of recruits from the ranks of exiled Czechoslovak citizens were created in Poland, France, and Great Britain, coordinated by the London-based exiled government. On the home turf, the resistance movement continued chiefly through massive demonstrations, which reached an apex in 1941. However, widespread arrests severely disrupted the underground networks and cut off radio networks between domestic and foreign components of the resistance movement, which were then reestablished by paratroopers dispatched into the Protectorate.

Operation Anthropoid

The Czechoslovak-British Operation Anthropoid was the code name for the assassination plot of the top Nazi leader Reinhard Heydrich, the chief of RSHA, an organization that included the Gestapo (Secret Police), SD (Security Agency) and Kripo (Criminal Police). Heydrich was the mastermind of the purge of Hitler's opponents as well as the genocide of Jews. Due to his reputation as the liquidator of resistance movements in Europe, he was sent to Prague in September 1941 to make order as the Protector of Bohemia and Moravia. The Protectorate was of strategic importance to Hitler’s plans, and Heydrich, dubbed the "Butcher of Prague," "The Blond Beast" or "The Hangman," wasted no time, handing out death sentences the day after his arrival.

With the fighting spirit in the Protectorate at a lull, the exiled military officials began planning an operation that would stir up the nation’s consciousness—six Czech and one Slovak paratroopers were chosen for the assassination of Heydrich, and two of them—Czech Josef Valčík and Slovak Josef Gabčik, executed it. Heydrich died of complications following surgery. The Gestapo tracked the paratroopers’ contacts and eventually discovered the assassins' hideaway in a Prague church. Three of them died in a shootout while trying to buy time for the others who were attempting to dig an escape route; the remaining four used their last bullets to take their lives.

Heydrich’s successor Karl Herrmann Frank had 10,000 Czechs executed as a warning, and two villages that assisted the paratroopers were leveled, with the adults murdered and young children sent to German families for re-education. The combined actions of the Gestapo and its confidantes virtually paralyzed the Czech resistance movement; on the other hand, the assassination bolstered Czechoslovakia’s prestige in the world and was crucial to the country’s securing of demands for an independent republic following the end of WWII.

End of War

Toward the end of the war, partisan movement was gaining momentum, and once the Allies were on the winning side, the political orientation of Czechoslovakia was high on the agenda of the two most influential exiled centers—the government in London and the communist officials in Moscow. Both endorsed the agreement on friendship, mutual assistance and postwar cooperation with the Soviet Union as a means to stem German expansion on one hand and the Soviet Union’s mingling into Czechoslovakia's internal affairs on the other.

Communist Czechoslovakia

Retaliation

After World War II, Czechoslovakia was reestablished. Carpathian Ruthenia was occupied by, and in June 1945, formally ceded to the Soviet Union, while Sudetenland Germans were expelled in an act of retaliation coined by the Beneš Decrees, which continue to fuel controversy between nationalist groups in the Czech Republic, Germany, Austria, and Hungary.[3] In total approximately 90 percent of the ethnic German population of Czechoslovakia was forced to leave. Wartime traitors and collaborators accused of treason along with ethnic Germans and Hungarians were expropriated.

Communist Takeover

The Communist takeover of Czechoslovakia was facilitated by the fact that most of the country had been liberated by the Red Army, as well as the overall social and economic downturn in Europe. In the 1946 parliamentary election, the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia emerged as the winner in the Czech lands while the Democratic Party won in Slovakia. In 1947, the Soviet Union and, consequently, its satellites, including Czechoslovakia, turned down the Marshall Plan, authored by U.S. Secretary of State George Marshall to address the economic needs of war-torn Europe.

In February 1948, the Communists seized power and sealed the country’s fate for the next 41 years. Terror reminiscent of Hitler’s Germany followed, with execution of political prisoners and prisoners of conscience, forced collectivization of agriculture, censorship, and land grabs. Economy was controlled by five-year plans and the industry was overhauled in compliance with Soviet wishes to focus on heavy industry, in which Czechoslovakia had been traditionally weak. The economy retained momentum vis-à-vis its Eastern European neighbors but grew increasingly weak vis-à-vis Western Europe.

In the early 1960s, Czechoslovakia came very close to extricating itself from the Eastern bloc, when the reformer Alexander Dubcek was appointed to the key post of First Secretary of the Czechoslovak Communist Party. Economic reforms were put in place that gradually grew into the reform of the overall political system, referred to as the Prague Spring. However, this glimmer of hope was crushed under the tanks of the Warsaw Pact armies in August 1968. Soviet tanks rolled into Czechoslovakia on the night of 20–21 August 1968.[4] The General Secretary of the Soviet Communist Party Leonid Brezhnev viewed this intervention as vital to the preservation of the Soviet, socialist system and vowed to intervene in any state that sought to replace Marxism-Leninism with capitalism.[5] In the week after the invasion there was a spontaneous campaign of civil resistance against the occupation. This resistance involved a wide range of acts of non-cooperation and defiance: this was followed by a period in which the Czechoslovak Communist Party leadership, having been forced in Moscow to make concessions to the Soviet Union, gradually put the brakes on their earlier liberal policies.[6] In April 1969 Dubcek was finally dismissed from the First Secretaryship of the Czechoslovak Communist Party.

The period of ‘normalization’ followed—the reforms were repealed, which, compounded by apolitical, military, and union purges thrust the country back into 1950s. The dissident movement, epitomized by the future Czech President Václav Havel, worked underground to counter the regime. Finally, the economic crisis in the 1980s facilitated the shift toward democracy.

Velvet Revolution

Mikhail Gorbachev’s address to the United Nations General Assembly in New York, in which he endorsed the rights for all nations to decide their own course, was among the first signs of the worldwide crumbling of the Communist empire. However, Communist authorities in Prague brutally dispersed ad hoc anti-regime demonstrations on November 17, 1989, in commemoration of the 1939 Nazi attack against university dormitories. This set in motion the Velvet Revolution, and the student-led protests in the metropolis soon spilled over to other parts of the country.

As Communist governments in neighboring countries were being toppled, borders with Western Europe were opened, and in December, President Gustáv Husák appointed the first government composed of largely non-Communists and resigned. Alexander Dubcek, who played a crucial role in the Prague Spring, became the voice of the federal parliament and Vaclav Havel the President. In June 1990, the first democratic elections since 1946 were held.

Toward Velvet Divorce

Discussion of the proposal to drop the country’s socialist attribute introduced in 1960 revealed a serious Czecho-Slovak conflict, with many Slovak deputies calling for the reinstatement of the original name, "Czecho-Slovakia," adopted by the Treaty of Versailles in 1918. The country was eventually renamed the Czech and Slovak Federal Republic in April 1990, but voices for Slovakia’s independence were mounting, and the fiercely nationalistic Slovak National Party, whose key agenda was independence, was founded around this time. Even prior to that, Slovakia's creation of the Foreign Relations Ministry in 1990 had signaled intensified independence efforts.

The June 1990 elections uncovered the growing rift between the two countries when Slovakia openly challenged President Havel's intervening in Slovak internal affairs. While the conservatives won a sweeping victory in the Czech Republic, Slovakia elected liberals. The cabinets of both countries were no longer largely composed of former dissidents, and although the federal government operated on the principle of symmetric power-sharing, disagreements between the republics escalated into Slovakia’s declaration of a sovereign state in July 1992, whereby its laws overrode the federal laws. Negotiations on the dissolution of the federal state took place for the remainder of the year, which was materialized on January 1, 1993, when two independent states—Slovakia and the Czech Republic—appeared on the map of Europe.

See also

- Alexander Dubcek

- Czech Republic

- Prague Spring

- Slovakia

- Vaclav Havel

- Velvet Revolution

- Dissolution of Czechoslovakia

Notes

- ↑ Peter Josika, Playing the Blame Game, Prague Post (July 6, 2005). Retrieved September 5, 2007.

- ↑ idnes News, Chcete zničit Prahu? ptal se Göring Háchy, March 15, 2007. (Czech Language) Retrieved September 5, 2007.

- ↑ Jacques Rupnik, The Other Central Europe, East European Constitutional Review (Winter/Spring 2002). Retrieved September 5, 2007.

- ↑ "Russia Invades Czechoslovakia: 1968 Year in Review," UPI.com (1968). Retrieved November 23, 2011.

- ↑ John Lewis Gaddis, The Cold War: A New History (New York, NY: The Penguin Press, 2006), 150.

- ↑ Philip Windsor and Adam Roberts, Czechoslovakia 1968: Reform, Repression and Resistance (London: Chatto & Windus, 1969), 97-143.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Gaddis, John Lewis. The Cold War: A New History. New York, NY: The Penguin Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0143038276

- Heimann, Mary. Czechoslovakia: The State That Failed. Yale University Press, 2011. ISBN 978-0300172423

- Windsor, Philip, and Adam Roberts. Czechoslovakia 1968: Reform, Repression and Resistance. London: Chatto & Windus, 1969. ASIN B01K1756RS

External Links

All links retrieved January 12, 2024.

Czech Language

- Gazdik, Jan. March 15, 2007. ”Do You Want to Destroy Prague? Goring Asked Hacha” iDnes News

- “Czechoslovak Resistance Movement in the West” Wars

- Mikulecky, Tomas. “Emergence of Czechoslovakia” Resources for Students

- “Second Czechoslovak Resistance Movement” Resources for Students

- “Second Czechoslovak Resistance Movement, the Role of the Three Kings and the Resistance Movement Role of Vladimir Krajina” History.

- ”Life in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia” Resources for Students

- “Assassination of Reynhard Heidrich” Resources for Students

- “Velvet Revolution or Eleven Days that Rocked Czechoslovakia” Totalitarianism

- “International Events of 1989” Totalitarianism

- “Political Processes in the Czech Socialist Republic 1948-1989” Resources for Students

- “Timeline of November 17 Demonstrations” Totalitarianism

- “Charter 77” Resources for Students

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.