Difference between revisions of "Carib" - New World Encyclopedia

(Images OK) |

|||

| Line 28: | Line 28: | ||

The social structure of Carib tribes were mostly [[Patriarchy|patriarchal]]. Women carried out primarily domestic duties and farming, and often lived in separate houses from men. However, women were highly revered and held substantial socio-political power. The Caribs usually lived in smaller groups, but these groups were often not exclusive from one another. The local [[democracy|self-government]] unit may have been the [[longhouse]] dwellings populated by men or women, typically run by one or more [[chieftain]]s reporting to an island [[tribal council|council]]. The tribes subsisted on [[fishing]] and small scale [[subsistence farming|farming]]. | The social structure of Carib tribes were mostly [[Patriarchy|patriarchal]]. Women carried out primarily domestic duties and farming, and often lived in separate houses from men. However, women were highly revered and held substantial socio-political power. The Caribs usually lived in smaller groups, but these groups were often not exclusive from one another. The local [[democracy|self-government]] unit may have been the [[longhouse]] dwellings populated by men or women, typically run by one or more [[chieftain]]s reporting to an island [[tribal council|council]]. The tribes subsisted on [[fishing]] and small scale [[subsistence farming|farming]]. | ||

| − | Because of a possible shared ancestry and years of assimilation, the Caribs shared many cultural similarities to the Tainos. After successfully conquering parts of the Caribbean, the Carib language quickly died out while the Arawakan language was maintained over the generations. This was the result of the invading Carib men usually killing the local men of the islands they conquered and taking Arawak wives who then passed on their own language to the children. For a time, Arawak was spoken primarily or exclusively by women and children, while adult men spoke Carib.<ref name=basso>Ellen B. Basso, ''Carib-Speaking Indians: Culture, Society, and Language'' ( | + | Because of a possible shared ancestry and years of assimilation, the Caribs shared many cultural similarities to the Tainos. After successfully conquering parts of the Caribbean, the Carib language quickly died out while the Arawakan language was maintained over the generations. This was the result of the invading Carib men usually killing the local men of the islands they conquered and taking Arawak wives who then passed on their own language to the children. For a time, Arawak was spoken primarily or exclusively by women and children, while adult men spoke Carib.<ref name=basso>Ellen B. Basso, ''Carib-Speaking Indians: Culture, Society, and Language'' (Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press, 1977, ISBN 0816504938).</ref> Eventually, as the first generation of Carib-Arawak children reached adulthood, the more familiar Arawak became the only language used in the small island societies. This language was called [[Island Carib]], even though it is not part of the Carib linguistic family. It is now extinct, but was spoken on the Lesser Antilles until the 1920s (primarily in [[Dominica]], [[Saint Vincent and the Grenadines|Saint Vincent]], and [[Trinidad and Tobago|Trinidad]]).<ref name=basso/> |

==Contemporary Life== | ==Contemporary Life== | ||

Revision as of 00:56, 18 February 2009

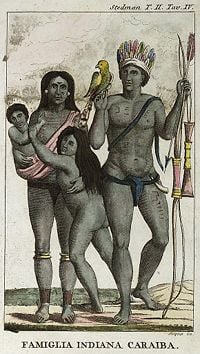

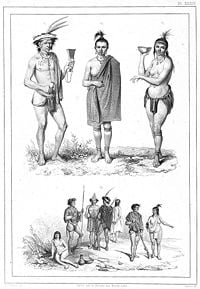

Carib, Island Carib or Kalinago people, after whom the Caribbean Sea was named, live in the Lesser Antilles islands. They are one of the two main tribes of Amerindian people who inhabited the Caribbean at the time of Christopher Columbus' discovery of the New World, the other being the Taino, also known as the Arawak. Like most of the indigenous peoples of the New World, the Carib suffered greatly from European conquest, and their descendants are now scattered throughout the Caribbean and South America, with the largest group living on the island of Dominica. Often the Carib are remembered for being ferocious warriors and for cannibalistic customs. As such, they have often been maligned by exaggerated early European propaganda, that over-looked their many accomplishments and skills, such as sailing, navigation, and basket weaving.

History

Although specific time tables are unknown, it is generally believed that the Taino were the first group to migrate from the Orinoco river area in South America to the islands of the Caribbean, sometime around 500 B.C.E.[1] The Carib followed soon afterward, invading many areas the inhabited by the Taino, killing and subjugating their predecessors. By 1400 C.E., the Carib controlled most of the West Antilles and areas of the cost of Venezuela.[2] After years of hostility, the two tribes settled into a general peace and cooperation, trading amongst each other and in some areas, such as the island of Dominica, the two cultures blended together.[1]

In 1493, during his second voyage to the New World, Christopher Columbus landed on the island the Carib had named Waitukubuli, which translates as "Tall is her beauty." Columbus renamed the island "Dominica," from the Latin Domingo, which means "Sunday."[1] Columbus' first encounter with the Carib was marked by the natives' hostility towards the Europeans; whereas history records Columbus was welcomed and made quick connections with the Tainos he encountered, Columbus and the Carib were almost immediately at odds with one another. After a few small but fierce skirmishes, Columbus and his men withdrew from the island of Dominica. Columbus named these natives Caniba, after the land other tribes referred to as Caritaba, where fierce cannibal warriors lived.[3] Eventually the Caribs warmed to the Europeans and trade developed. However, further European conquest soon proved the disastrous for the Caribs.

The 1635 invasion and seizure by the French military made the island of Martinique part of the French colonial empire. Using their overwhelming military superiority, the French forces of Pierre Belain d'Esnambuc subjugated the indigenous Carib peoples to French colonial rule. Through Cardinal Richelieu, France gave the island to the Company of the American Islands (Compagnie des Isles d'Amerique). French Law was imposed on the conquered inhabitants and the Jesuits arrived to convert them to the Roman Catholic Church.[4] When the Caribs could not be sufficiently induced to supply labor for building and maintaining the sugar and cocoa plantations the Company desired, in 1636 King Louis XIII authorized the abduction of slaves from Africa for transportation to Martinique and other parts of the French West Indies.[5] The Caribs revolted against French rule and under Governor Charles Houel sieur de Petit Pré the "Carib Expulsion" was launched against them in 1660. Many were slaughtered; those who survived were taken captive and expelled from the island, never to return.

By the eighteenth century the British Empire had moved in and begun to threaten the French and Spanish colonies. In 1763 the British captured the island of Dominica and forced the Carib onto a reserve of 232 acres (94 ha), while the British took control of the rest of the island and consumed its natural wealth and resources.[3] The Carib on Dominica, although subjugated onto a small part of the Island, fared better than other tribes on other islands.

In 1796, the British Empire took control of large parts of the Caribbean. The population of Saint Vincent, known as the "Black Carib" because a slave ship had wrecked on the island in the seventeenth century and surviving African slaves had intermarried with the Carib Indians, was relocated to an island off the coast of Honduras where they suffered from disease and mal-treatment. However, enough were able to make it off the island and thrive in small numbers in Central America.[2] Across the rest of the Caribbean, the Carib and other indigenous tribes were decimated in numbers by the European suppression, disease, and the Inquisition. By the beginning of the twentieth century, the Carib existed primarily on the reserve in Dominica with a few groups scattered in Central America.

Culture

Much of the historical narrative of the Carib culture has focused upon their aggressive and war-like characteristics. The Taino's experiences of fighting and being conquered by the Carib influenced Columbus' account of the Carib tribes. In fact, Columbus' second hand knowledge of, and limited personal contact with, the Carib led to the creation of the word cannibal. The English word "cannibal" originated from the Carib word karibna ("person"), as recorded by Columbus as a name for the Caribs.[6] The existence of cannibalism has been challenged by some anthropologists as well as contemporary Carib.[7] However, there is significant historic evidence that instances of cannibalism were spiritual acts connected to deeply held war rituals; purportedly, male warriors would eat small amounts of the flesh of their enemies so as to assume their characteristics.[6] This ritual eating of human flesh took place before a raiding expedition or during initiation, when it was hoped young men would inherit the bravery of a distinguished warrior.[8] More commonly, the Carib would collect the limbs of victims as trophies, and had a tradition of keeping the bones of their ancestors in their houses. The belief that the physical remains of the dead could be used to harvest some residual power of the living was central to Carib spirituality.

Beyond the connection to warfare and sacrifice, the Caribs shared a more general religious outlook with the Tainos. Both are generally thought to have been polytheists, who believed in nature spirits and practiced forms of Shamanism. They believed in an evil spirit called Maybouya who had to be placated in order to avoid harm. The chief function of their shamans was to heal the sick with herbs and to cast spells which would keep Maybouya at bay. The shamans was very important and underwent special training instead of becoming warriors. As they were held to be the only people who could avert evil, they were treated with great respect. Their ceremonies were accompanied with sacrifices. As with the Taino, tobacco played a large part in these religious rites.

The fact they were able to migrate from the continent to various islands in the Caribbean, as well as conquer already populated islands are testaments both to their skills as navigators and boat builders. The Carib were also skilled at basket weaving and pottery.

The social structure of Carib tribes were mostly patriarchal. Women carried out primarily domestic duties and farming, and often lived in separate houses from men. However, women were highly revered and held substantial socio-political power. The Caribs usually lived in smaller groups, but these groups were often not exclusive from one another. The local self-government unit may have been the longhouse dwellings populated by men or women, typically run by one or more chieftains reporting to an island council. The tribes subsisted on fishing and small scale farming.

Because of a possible shared ancestry and years of assimilation, the Caribs shared many cultural similarities to the Tainos. After successfully conquering parts of the Caribbean, the Carib language quickly died out while the Arawakan language was maintained over the generations. This was the result of the invading Carib men usually killing the local men of the islands they conquered and taking Arawak wives who then passed on their own language to the children. For a time, Arawak was spoken primarily or exclusively by women and children, while adult men spoke Carib.[9] Eventually, as the first generation of Carib-Arawak children reached adulthood, the more familiar Arawak became the only language used in the small island societies. This language was called Island Carib, even though it is not part of the Carib linguistic family. It is now extinct, but was spoken on the Lesser Antilles until the 1920s (primarily in Dominica, Saint Vincent, and Trinidad).[9]

Contemporary Life

Today, small pockets of ethnic Carib communities are scattered throughout the Caribbean and South America, in such places as Trinidad, Venezuela, Colombia, Brazil, French Guiana, Guyana and Suriname. The largest community lives on the island of Dominica, in the original reservation established for the Carib by the British when they seized control of the island in the eighteenth century. An estimated community of 3,400 people like in this reservation, which over the years has become a tourist attraction of the island.[8] This community elects their own Chiefs who serve for four years at a time, and officials who represent the Carib in the Dominica government.[10] These communities attempt to keep their historical traditions and culture alive, partially for preservation and also for economic reasons, as the Carib territories are marketed as tourist attractions where visitors can view cultural acts such as dance as well as purchase authentic crafts and artwork. The Carib community has established the Karifuna Cultural Group which works to preserve culture and to educate about Carib history and tradition.[10]

The Santa Rosa Carib Community (SRCC) is the major organization of indigenous people in Trinidad and Tobago. The Caribs of Arima are descended from the original Amerindian inhabitants of Trinidad; Amerindians from the former encomiendas of Tacarigua and Arauca (Arouca) were resettled to Arima between 1784 and 1786. The SRCC was incorporated in 1973 to preserve the culture of the Caribs of Arima and maintain their role in the annual Santa Rosa Festival (dedicated to Santa Rosa de Lima, the first Catholic saint canonized in the New World).

Today, the Garinagu (singular: Garifuna) descendants of Carib, Arawak and African people referred to by the British colonial administration as "Black Carib" live primarily in Central America. They live along the Caribbean Coast in Belize, Guatemala, Nicaragua, and Honduras including the mainland, and on the island of Roatán. There are also diaspora communities of Garinagu in the United States, particularly in Los Angeles, Miami, New York and other major cities.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Kevin Menhinick, "The Caribs in Dominica: Karifuna Cultural Group," Caribbean Taino News Service, 1997. Retrieved February 8, 2009.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Jan Rogonzinski, A Brief History of the Caribbean: From the Arawak and Carib to the Present (Plume, 2000, ISBN 0452281938).

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Kwabs.com "Caribbean Indigenous people" Retrieved February 7, 2009.

- ↑ Prefecture Région Martinique, Martinique' Institutional History Maryanne Dassonville (trans.), 2007. Retrieved February 18, 2009.

- ↑ James L. Sweeney, "Caribs, Maroons, Jacobins, Brigands, and Sugar Barons: The Last Stand of the Black Caribs on St. Vincent," African Diaspora Archaeology Network, March 2007. Retrieved February 8, 2009.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Laurance R. Goldman (Ed.), The Anthropology of Cannibalism (Bergin & Garvey Paperback, 1999, ISBN 0897895975)

- ↑ Lennox Honychurch, The Dominica Story: A History of the Island (Macmillan Caribbean, 1995, ISBN 0333627768)

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Simon Lee, "An Artist of the Floating World," The Caribs of Dominica, 2000. Retrieved February 17, 2009.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Ellen B. Basso, Carib-Speaking Indians: Culture, Society, and Language (Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press, 1977, ISBN 0816504938).

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 A Virtual Dominica "The Carib Indians." Retrieved February 12, 2009.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Allaire, Louis (1997). "The Caribs of the Lesser Antilles." In Samuel M. Wilson, The Indigenous People of the Caribbean, pp. 180–185. Gainesville, Florida: University of Florida. ISBN 0813015316

- Steele, Beverley A. (2003). "Grenada, A history of its people." Macmillan Education, pp11-47

- Honeychurch, Lennox, The Dominica Story, MacMillan Education 1995.

- Davis, D and Goodwin R.C. "Island Carib Origins: Evidence and non-evidence" American Antiquity vol.55 no.1(1990).

- Eaden, John, "The Memoirs of Père Labat," 1693-1705, Frank Cass 1970.

- Gordon, Raymond G., Jr. (ed.). Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Fifteenth edition. Dallas, TX: SIL International, 2005. Retrieved February 17, 2009.

- Basso, Ellen B. Carib-Speaking Indians: Culture, Society, and Language. University of Tucson, AZ: Arizona Press, 1977. ISBN 0816504938

- Rogonzinski, Jan A Brief History of the Caribbean: From the Arawak and Carib to the Present. New York, NY: Plume, 2000. ISBN 0452281938

- Goldman, Laurance R. (ed.) The Anthropology of Cannibalism. Westport, CT: Bergin & Garvey Paperback, 1999. ISBN 0897895975

External links

- Etnolinguistica.Org: online resources on native South American languages

- Ethnologue report for Carib languages

- http://www.cariblanguage.org/galibi.html

- Rosetta Project entry

- Official Website of the Santa Rosa Carib Community

- O! Dominica Land of Beautiful Indigenous People

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.