Bubonic plague

| Plague Classification and external resources | |

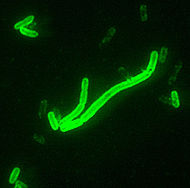

| Yersinia pestis seen at 2000x magnification. This bacterium, carried and spread by fleas, is the cause of the various forms of the disease plague |

Bubonic plague is the best-known variant of the deadly infectious disease called plague, which is caused by the enterobacteria Yersinia pestis. The epidemiological use of the term plague is currently applied to bacterial infections that cause buboes, although historically the medical use of the term plague has been applied to pandemic infections generally.

Infection/transportation

Plague is primarily a disease of rodents. Infection of human beings most often occurs when a person is bitten by an infected flea that has fed on an infected rodent. The bacteria multiply inside the flea, sticking together to form a plug that blocks its stomach and causes it to begin to starve. The flea then voraciously bites a host and continues to feed, even though it is unable to satisfy its hunger. During the feeding process, blood cannot flow into the blocked stomach, and consequently the flea vomits blood tainted with the bacteria back into the bite wound. The Bubonic plague bacterium then infects a new host, and the flea eventually dies from starvation. Any serious outbreak of plague is usually started by other disease outbreaks in rodents, or some other crash in the rodent population. During these outbreaks, infected fleas that have lost their normal hosts seek other sources of blood.

In 1894, two bacteriologists, Alexandre Yersin and Shibasaburo Kitasato, independently isolated the bacterium in Hong Kong responsible for the Third Pandemic. Though both investigators reported their findings, a series of confusing and contradictory statements by Kitasato eventually led to the acceptance of Yersin as the primary discoverer of the organism. Yersin named it Pasteurella pestis in honour of the Pasteur Institute, where he worked. But in 1967 the genus was changed to Yersinia pestis, in honour of Yersin .

Yersin also reported that rats were affected by plague bacteria not only during epidemics but they were also often affected preceding epidemics in humans. Villagers in China and India noticed that when large numbers of rats were found dead, plague outbreaks in people soon followed.

In 1898, the French scientist Paul-Louis Simond (who had also come to China to battle the Third Pandemic) discovered the rat-flea vector relationship that drives the disease. He had noted that persons who became ill did not have to be in close contact with each other to acquire the disease. In Yunnan, China, inhabitants would flee from their homes as soon as they saw dead rats, and on the island of Formosa (Taiwan), residents considered handling dead rats a risk for developing plague. These observations led him to suspect that the flea might be an intermediary factor in the transmission of plague, since people acquired plague only if they were in contact with recently dead rats, but not affected if they touched rats that had been dead for more than 24 hours. In a now classic experiment, Simond demonstrated how a healthy rat died of plague after infected fleas had jumped to it from a plague-dead rat.

Clinical features

There are three forms of plague : (1) bubonic, (2) septicemic and (3) pneumonic. Bubonic plague becomes evident three to eight days after the infection. Initial symptoms are chills, fever, diarrhea, headaches, and the swelling of the infected lymph nodes, as the bacteria replicate there. If untreated, the rate of mortality for bubonic plague is 50-90% (Hoffman 1980).

In septicemic plague, there is bleeding into the skin and other organs, which creates black patches on the skin. There are bite-like bumps on the skin, commonly red and sometimes white in the center. Untreated septicemic plague is universally fatal, but early treatment with antibiotics reduces the mortality rate to between 4 and 15 percent (Wagle 1948) (Meyer 1950)(Datt Gupta 1948). People who die from this form of plague often die on the same day symptoms first appear.

The pneumonic plague infects the lungs, and with that infection comes the possibility of person-to-person transmission through respiratory droplets. The incubation period for pneumonic plague is usually between two and four days, but can be as little as a few hours. The initial symptoms, of headache, weakness, and coughing with hemoptysis, are indistinguishable from other respiratory illnesses. Without diagnosis and treatment, the infection can be fatal in one to six days; mortality in untreated cases may be as high as 95%.

Treatment

An Indian doctor ,Vladimir Havkin, was the first to invent and test a plague antibiotic.

The traditional treatments are:

- Streptomycin 30 mg/kg intramuscular twice daily for 7 days

- Chloramphenicol 25–30 mg/kg single dose, followed by 12.5–15 mg/kg four times daily

- Tetracycline 2 g single dose, followed by 500 mg four times daily for 7–10 days (not suitable for children)

More recently,

- Gentamicin 2.5 mg/kg intravenous or intramuscular twice daily for 7 days

- Doxycycline 100 mg (adults) or 2.2 mg/kg (children) orally twice daily have also been shown to be effective (Mwengee 2006)

History

The earliest (though unvalidated) account describing a possible plague epidemic is found in I Samuel 5:6 of the Hebrew Bible (Torah). In this account, the Philistines of Ashdod were stricken with a plague for the crime of stealing the Ark of the Covenant from the Children of Israel. These events have been dated to approximately the second half of the eleventh century B.C.E. The word "tumors" is used in most English translations to describe the sores that came upon the Philistines. The Hebrew, however, can be interpreted as "swelling in the secret parts". The account indicates that the Philistine city and its political territory were stricken with a "ravaging of mice" and a plague, bringing death to a large segment of the population.

In the second year of the Peloponnesian War (430 B.C.E.), Thucydides described an epidemic disease which was said to have begun in Ethiopia, pass through Egypt and Libya, then come to the Greek world. In the Plague of Athens, the city lost possibly one third of its population, including Pericles. Modern historians disagree on whether the plague was a critical factor in the loss of the war. This epidemic has long been considered an outbreak of plague, however, because of Thucydides' description, modern scholars dispute that it was indeed plague. Many modern scholars feel that typhus, smallpox or measles may better fit the descriptions. A recent study of the DNA found in the dental pulp of plague victims suggests that typhoid was actually responsible. Other scientists dispute these findings, citing serious methodologic flaws in the DNA study.

In the first century AD, Rufus of Ephesus, a Greek anatomist, refers to an outbreak of plague in Libya, Egypt, and Syria. He records that Alexandrian doctors named Dioscorides and Posidonius described symptoms including acute fever, pain, agitation, and delirium. Buboes—large, hard, and non-suppurating—developed behind the knees, around the elbows, and "in the usual places." The death toll of those infected was very high. Rufus also wrote that similar buboes were reported by a Dionysius Curtus, who may have practiced medicine in Alexandria in the third century B.C.E. If this is correct, the eastern Mediterranean world may have been familiar with bubonic plague at that early date (Simpson 1905, Patrick 1967)

Plague of Justinian

The Plague of Justinian in A.D. 541–542 is the first known pandemic on record, and marks the first firmly recorded pattern of bubonic plague. This outbreak is thought to have originated in Ethiopia or Egypt. The huge city of Constantinople imported massive amounts of grain, mostly from Egypt, to feed its citizens. The grain ships may have been the source of contagion for the city, with massive public granaries nurturing the rat and flea population. At its peak the plague was killing 10,000 people in Constantinople every day and ultimately destroyed perhaps 40 percent of the city's inhabitants. It went on to destroy up to a quarter of the human population of the eastern Mediterranean.

In A.D. 588 a second major wave of plague spread through the Mediterranean into what is now France. A maximum of 25 million dead is considered a reasonable estimate. An outbreak of it in the A.D 560s was described in A.D. 790 as causing "swellings in the glands...in the manner of a nut or date" in the groin "and in other rather delicate places followed by an unbearable fever". While the swellings in this description have been identified by some as buboes, there is some contention as to whether the pandemic should be attributed to the bubonic plague organism, Yersinia pestis, known in modern times.

Black Death

During the mid-14th century, from about 1347 to 1350, the Black Death, a massive and deadly pandemic, swept through Eurasia, killing approximately one third of the population (according to some estimates) and changing the course of Asian and European history. It is estimated that anywhere from a quarter to two-thirds of Europe's population became victims to the plague, making the Black Death the largest death toll from any known non-viral epidemic. While accurate statistical data do not exist, it is estimated that 1/4 of England's population (4.2 million) died. While a higher percentage of individuals is likely to have died in Italy. Northeastern Germany, Bohemia, Poland and Hungary, on the other hand, are believed to have suffered less ,with no estimates for Russia or the Balkans .

In many European cities and countries, the presence of Jews was blamed for the arrival of the plague, and they were killed in pogroms or expelled.

The Black Death continued to strike parts of Europe throughout the 14th ,the 15th and the 16th centuries with constantly falling intensity and fatality, strongly suggesting rising resistance due to genetic selection. Some have argued that changes in hygiene habits and strong efforts within public health and sanitation had a significant impact on the rate of infection. Also, medical practices of the time were based largely on spiritual and astrological factors, but towards the end of the plague doctors took a more scientific approach to helping patients.

Nature of the disease

In the early 20th century, following the identification by Yersin and Kitasato of the plague bacterium that caused the late 19th and early 20th century Asian bubonic plague (the Third Pandemic), most scientists and historians came to believe that the Black Death was an incidence of this plague, with a strong presence of the more contagious pneumonic and septicemic varieties increasing the pace of infection, spreading the disease deep into inland areas of the continents. It was claimed that the disease was spread mainly by black rats in Asia and that therefore there must have been black rats in north-west Europe at the time of the Black Death to spread it, although black rats are currently rare except near the Mediterranean. This led to the development of a theory that brown rats had invaded Europe, largely wiping out black rats, bringing the plagues to an end, although there is no evidence for the theory in historical records. The view that the Black Death was caused by Yersinia pestis has been incorporated into medical textbooks throughout the 20th century and has become part of popular culture, as illustrated by recent books (Kelly 2005).

Many modern researchers have argued that the disease was more likely to have been viral (that is, not bubonic plague), pointing to the absence of rats from some parts of Europe that were badly affected and to the conviction of people at the time that the disease was spread by direct human contact. According to the accounts of the time the black death was extremely virulent, unlike the 19th and early 20th century bubonic plague. The bubonic plague theory has been comprehensively rebutted by Samuel K. Cohn (2003A). In the Encyclopedia of Population, he points to five major weaknesses in this theory:

- very different transmission speeds — the Black Death was reported to have spread 385 km in 91 days in 664, compared to 12-15 km a year for the modern Bubonic Plague, with the assistance of trains and cars

- difficulties with the attempt to explain the rapid spread of the Black Death by arguing that it was spread by the rare pneumonic form of the disease — in fact this form killed less than 0.3% of the infected population in its worst outbreak (Manchuria in 1911)

- different seasonality — the modern plague can only be sustained at temperatures between 50 and 78 degrees F (10 and 26 degrees C) and requires high humidity, while the Black Death occurred even in Norway in the middle of the winter and in the Mediterranean in the middle of hot dry summers

- very different death rates — in several places (including Florence in 1348) over 75% of the population appears to have died; in contrast the highest mortality for the modern Bubonic Plague was 3% in Bombay (now known as Mumbai) in 1903

- the cycles and trends of infection were very different between the diseases — humans did not develop resistance to the modern disease, but resistance to the Black Death rose sharply, so that eventually it became mainly a childhood disease

Cohn also points out that while the identification of the disease as having buboes relies on accounts of Boccaccio and others, they described buboes, abscesses, rashes and carbuncles occurring all over the body, mostly concentrated around the neck or behind the ears. In contrast, the modern disease rarely has more than one bubo, most commonly in the groin, and is not characterised by abscesses, rashes and carbuncles.

Third Pandemic

The Third Pandemic began in China in 1855, spreading plague to all inhabited continents and ultimately killing more than 12 million people in India and China alone. Casualty patterns indicate that waves of this pandemic may have come from two different sources. The first was primarily bubonic and was carried around the world through ocean-going trade, transporting infected persons, rats, and cargos harboring fleas. The second, more virulent strain was primarily pneumonic in character, with a strong person-to-person contagion. This strain was largely confined to Manchuria and Mongolia. Researchers during the "Third Pandemic" identified plague vectors and the plague bacterium (see above), leading in time to modern treatment methods.

The last significant European outbreak of plague occurred in Russia in A.D. 1877–1889 in rural areas near the Ural Mountains and the Caspian Sea. Efforts in hygiene and patient isolation reduced the spread of the disease, with approximately 420 deaths in the region. Significantly, the region of Vetlianka is near a population of the bobak marmot, a small rodent, which may be a very dangerous plague reservoir.

The bubonic plague continued to circulate through different ports globally for the next 50 years. However, it was primarily found in Southeast Asia. An epidemic in Hong Kong in 1894 had particularly high death rates, greater than 75%. As late as 1897, medical authorities in the European powers organized a conference in Venice, seeking ways to keep the plague out of Europe. The disease reached the Republic of Hawaii in December of 1899, and in an unprecedented catastrophe, the Board of Health burned down all of Honolulu’s Chinatown on January 20, 1900. Plague finally reached the United States later that year in San Francisco.

Although the outbreak that began in China in 1855 is conventionally known as the Third Pandemic, (the First being the Plague of Justinian and the second being the Black Death), it is unclear whether there have been fewer, or more, than three major outbreaks of bubonic plague. Most modern outbreaks of bubonic plague amongst humans have been preceded by a striking, high mortality amongst rats, yet this phenomenon is absent from descriptions of some earlier plagues, especially the Black Death. The buboes, or swellings of lymph nodes in the groin, that are especially characteristic of plague , are also a feature of other diseases such as syphilis and gonorrhea.

Plague as a biological weapon

Plague has a long history as a biological weapon. Historical accounts from medieval Europe detail the use of infected animal carcasses, such as cows or horses, and human carcasses, by Mongols, Turks and other groups, to contaminate enemy water supplies. Plague victims were also reported to have been tossed by catapult into cities under siege.

During World War II, the Japanese Army developed weaponised plague, based on the breeding and release of large numbers of fleas. During the Japanese occupation of Manchuria, Unit 731 deliberately infected Chinese civilians and prisoners of war with the plague bacterium. These subjects, called "logs", were then studied by dissection, others vivisection while still conscious. After World War II, both the United States and the Soviet Union developed means of weaponising pneumonic plague. Experiments included various delivery methods, vacuum drying, sizing the bacterium, developing strains resistant to antibiotics, combining the bacterium with other diseases (such as diphtheria), and genetic engineering. Scientists who worked in USSR bio-weapons programs have stated that the Soviet effort was formidable and that large stocks of weaponised plague bacteria were produced. Information on many of the Soviet projects is largely unavailable. Aerosolized pneumonic plague remains the most significant threat.

Contemporary cases

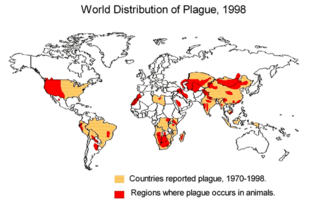

Two species of non-plague Yersinia, Yersinia pseudotuberculosis and Yersinia enterocolitica, still exist in fruit and vegetables from the Caucasus Mountains east across southern and central Russia, to Kazakhstan, Mongolia, and parts of China; in Southwest and Southeast Asia, Southern and East Africa (including the island of Madagascar); in North America, from the Pacific Coast eastward to the western Great Plains, and from British Columbia south to Mexico; and in South America in two areas: the Andes mountains and Brazil. There is no plague-infected animal population in Europe or Australia.

- It was reported in September 2005 (ABC NEWS) that three mice infected with Yersinia pestis apparently disappeared from a laboratory belonging to the Public Health Research Institute,

- On 19 April, 2006, CNN News and others reported a case of plague in Los Angeles, California, the first reported case in that city since 1984.

- In May 2005, KSL Newsradio reported a case of plague found in dead field mice and chipmunks at Natural Bridges about 40 miles west of Blanding in San Juan County, Utah.

- In May 2005, The Arizona Republic reported a case of plague found in a cat.

- In the U.S., about half of all food cases of plague since 1970 have occurred in New Mexico. There were 2 plague deaths in the state in 2006, the first fatalities in 12 years.[1]

- One hundred deaths resulting from pneumonic plague were reported in Ituri district of the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo in June 2006. Control of the plague was proving difficult due to the ongoing conflict.[2]

See also

- Black Death

- Epidemic

- Medieval demography

- Plague of Justinian

- Third Pandemic

- Ring around the rosey

- List of Bubonic plague outbreaks

- Plague columns

- Plague doctor

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ABC News (15 September 2005). Plague-Infected Mice Missing From N.J. Lab. http://abcnews.go.com/Health/story?id=1128953

- BBC News (14 June 2006). Congo ,D.R. 'plague' leaves 100 dead. Retrieved on 2006-12-15

- Cohn, S.K. 2003A. The Black Death Transformed: Disease and Culture in Early Renaissance Europe. A Hodder Arnold, 336. ISBN 0-340-70646-5.

- Cohn, S.K. 2003B. Black Death in Encyclopedia of Population 1:98-101.101 . published by Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 0-02-865677-6

- Datt Gupta,A.K. 1948. A short note on plague cases treated at Campbell Hospital. Ind Med Gaz 83: 150–1.

- Hoffman, S.L. 1980. Plague in the United States: the "Black Death" is still alive. Annals of Emergency Medicine 9: 319–22.

- Kelly, J. 2005. The Great Mortality: An Intimate History of the Black Death, the Most Devastating Plague of All Time. New York: HarperCollins Publishers Inc., 2005. ISBN 0-06-000692-7.

- KSL Newsradio (16 May 2005). Campground Closes Because of Plague. ). Retrieved on 2006-12-15.

- Meyer,K.F. 1950. Modern therapy of plague. J Am Med Assoc 144: 982–5.

- Mwengee, W. et al. 2006. Treatment of Plague with Genamicin or Doxycycline in a Randomized Clinical Trial in Tanzania. Clin. Infect. Dis. 42 (5): 614–21.

- Plague Data in New Mexico. New Mexico Department of Health. Retrieved on 2006-12-15.

- Patrick, A. 1967. "Disease in Antiquity: Ancient Greece and Rome," in Diseases in Antiquity, editors: Don Brothwell and A. T. Sandison. Springfield, Illinois; Charles C. Thomas.

- Simpson, W. J. 1905.A Treatise on Plague. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- The Arizona Republic (16 May 2005)Cat tests positive for bubonic plague.Http://www.azcentral.com/health/news/articles/0628PlagueCat28-ON.html. accessdate = 2006-12-15

- Wagle, P.M. 1948. Recent advances in the treatment of bubonic plague. Indian J Med Sci 2: 489–94.

Bibliography

- Biraben, Jean-Noel. Les Hommes et la Peste The Hague 1975.

- Buckler, John and Bennet D. Hill and John P. McKay. "A History of Western Society, 5th Edition." New York: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1995.

- Cantor, Norman F., In the Wake of the Plague: the Black death and the World It Made New York: Harper 2001.

- de Carvalho, Raimundo Wilson; Serra-Freire, Nicolau Maués; Linardi, Pedro Marcos; de Almeida, Adilson Benedito; and da Costa, Jeronimo Nunes (2001). Small Rodents Fleas from the Bubonic Plague Focus Located in the Serra dos Órgãos Mountain Range, State of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz 96(5), 603–609. PMID 11500756. this manuscript reports a census of potential plague vectors (rodents and fleas) in a Brazilian focus region (i.e. region associated with cases of disease); free PDF download Retrieved 2005-03-02

- Cohn, Samuel K. (2003). The Black Death Transformed: Disease and Culture in Early Renaissance Europe. A Hodder Arnold, 336. ISBN 0-340-70646-5.

- Gregg, Charles T. Plague!: The shocking story of a dread disease in America today. New York, NY: Scribner, 1978, ISBN 0-684-15372-6.

- McNeill, William H. Plagues and People. New York: Anchor Books, 1976. ISBN 0-385-12122-9. Reprinted with new preface 1998.

- Mohr, James C. Plague and Fire: Battling Black Death and the 1900 Burning of Honolulu's Chinatown. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2005, ISBN 0-19-516231-5.

- Orent, Wendy. Plague: The Mysterious Past and Terrifying Future of the World's Most Dangerous Disease. New York: Free Press, 2004. ISBN 0-7432-3685-8.

- Platt, Colin. King Death: The Black Death and its Aftermath in Late-Medieval England Toronto University Press, 1997.

- Spielvogel, Jackson J. Western Civilization: A Brief History Vol. 1: to 1715. Belmont, Calif.: West/Wadsworth, 1999, Ch. 3, p. 56, paragraph 2. ISBN 0-534-56062-8.

External links

- World Health Organization

- Health topic

- Communicable Disease Surveillance & Response - Impact of plague & Information resources

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- CDC Plague map world distribution, publications, information on bioterrorism preparedness and response regarding plague

- Infectious Disease Information more links including travelers' health

- Symptoms, causes, pictures of bubonic plague

- Secrets of the Dead . Mystery of the Black Death PBS

- Flea As Weapon

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

- ↑ Plague Data in New Mexico. New Mexico Department of Health. Retrieved 2006-12-15.

- ↑ DR Congo 'plague' leaves 100 dead. BBC News (14 June 2006). Retrieved 2006-12-15.