Bernard of Clairvaux

| Saint Bernard of Clairvaux | |

|---|---|

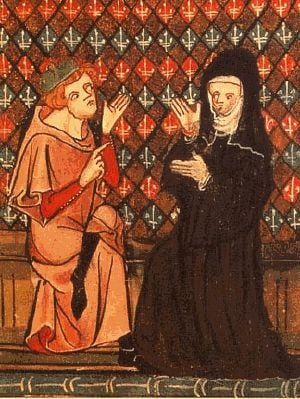

Bernard of Clairvaux, in a medieval illuminated manuscript | |

| Abbot and Doctor of the Church | |

| Born | 1090 in Fontaines, France |

| Died | August 21 1153 in Clairvaux, France |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholic Church, Anglican Church |

| Canonized | 1174 |

| Feast | August 20 |

| Attributes | with the Virgin Mary, a beehive, dragon, quill, book, or dog |

| Patronage | farm and agriculture workers, Gibraltar, Queens' College, Cambridge |

Saint Bernard of Clairvaux (1090 -August 21, 1153) was a French abbot and the primary builder of the reforming Cistercian monastic order. The dominant voice of Christian conscience in the second quarter of the twelth century CE, his authority was decisiving in ending the papal schism of 1130. A conservative in theological matters, he forcefully opposed the early scholastic movement of the twelth century, denouncing its great exponent Peter Abelard as a heretic and forcing him into retirement from his teaching position at the University of Paris. In association with his former protege, Pope Eugenius III, he was the primary preacher of the Second Crusade, a cause which failed to achieve the glories he expected of it.

Devoted to promoting the veneration of the Virgin Mary, Bernard is credited as being a major influence in promoting a personal relationship with God's compassion and mercy through Mary's intercession. By all accounts he was a deeply spiritual, acestic, and sincere example of the values he promoted. He was canonized as a saint in 1174 and declared a Doctor of the Church in 1830.

Early life

Brernard was born at Fontaines, near Dijon, in France, into the noble class. His father, Tescelin, was a knight of the lower nobility, and his mother, Aleth, was a daughter of the noble house of Montbard. She was a woman distinguished for her piety, but died while Bernard was still a boy. Constitutionally unfit for for the military of his father, his own disposition as well as his mother's early influence directed him toward a career the church.

Bernard's desire to enter a monastery, however, was opposed by his relatives, who sent him against his will to study at Châtillon-sur-Seine in order to qualify him for high ecclesiastical office. Bernard's resolution to become a monk was not shaken, however. It is a testimony to the nature of his personality that when he at finally decided to join the Benedictine community at Citeaux, he took with him his brothers, several of his his relations and a number of friends.

Abbot of Clairvaux

The keynote of Cistercian life was a return to a literal observance of the Rule of Saint Benedict, rejecting pompous ecclesiastical trappings that characterized some Benedictine monasteries and the Church generally during this period. The most striking feature in the Cistercian reform was the return to manual labor, especially field-work.

After Bernard's arrival with his 30 companions in 1114, the small community at Cîteaux grew so rapidly that it was soon able to send out offshoots. One of these, Clairvaux, was founded in 1115, in a wild valley of a tributary of the AubeRiver, on land given by Count Hugh of Troyes. There Bernard was appointed abbot, a remarkable rise for such a recent initiate. Though nominally subject to Cîteaux, Clairvaux soon became the most important Cistercian house, owing to the fame and influence of Bernard.

Wider influence

Despite an avowed intention to devote himself strictly to monastic concerns, Bernard soon involved himself in the affairs of the outside world. By 1124, when Pope Honorius II was elected, Bernard was already reckoned among the greatest of French churchmen. He now shared in the most important ecclesiastical discussions, and papal legates sought his counsel.

Thus in 1129 he was invited by Cardinal Matthew of Albano to the Council of Troyes. An enthusaiastic supporter of the spirit of the Crusades, Bernard was instrumental at Troyes in obtaining official recognition of the Knights Templar—active as a military force with religious roots since the end of the First Crusade—as an authorized religious order.

In the following year, at the synod of Châlons-sur-Marne, he ended the crisis arising out of certain charges brought against Henry, Bishop of Verdun, by persuading the bishop to resign.

The schism of 1130–1138

Bernard’s significance reached its zenith after the death of Pope Honorius (1130) and the disputed election that followed, in which Bernard became the champion of Innocent II. A group of eight influential Cardinals, seeking to stave off the influence of powerful Roman families quickly elected Bernard's former pupil Cardinal Gregory Papareschi as Innocent II, a proponent of the Cistercian reforms. Their act, however, was not in accordance in Canon Law. In a formal conclave, Cardinal Pietro Pierleoni was elected by a narrow margin as Pope Anacletus II.

Innocent, denounced in Rome as an "anti-Pope" was forced to flee north. In a synod convoked by Louis the Fat at Etampes in April 1130, Bernard successfully asserted Innocent's claims against those of Anacletus and became Innocent's most influential supporter. He threw himself into the contest with characteristic ardor.

Although Rome supported Anacletus, France, England, Spain and Germany declared for Innocent. Innocent traveled from place to place, with the powerful abbot of Clairvaux at his side. He even stayed at Clairvaux itself, a humble abode so far as its buildings were concerned, but having a strong reputation for piety, in conrast with Rome's fame for pomp and corruption.

Bernard accompanied Innocent to parley with Lothair II, the Holy Roman Emperor]], who would become a key political supporter of Innocent's cause. In 1133, the year of the emperor's first expedition to Rome, Bernard was in Italy persuading the Genoese to make peace with Pisa, since Innocent had need of both.

Anacletus now found himself in a far less advantageous position. In addition, although he had been a well respected Cardinal, the fact of his Jewish descent now scandalized some quaters and the "anti-pope" label now stuck to him as readily as Innocent. The embolded Innocent now traveled to Rome where Bernard, never one to compromise, shrewdly resisted an attempt reopen negotiations with Anacletus.

The papal residence at the Castel Sant'Angelo, however, was held by Anacletus, and he was supported by the Norman King Roger II of Sicily. He was thus too strong to be subdued by force, for Lothair, though crowned by Innocent in St. Peter's, was distracted militarily by a quarrel with the house of Hohenstaufen in his home area. Again Bernard came to the rescue. In the spring of 1135 he traveled to Bamberg where successfully persuaded Frederick Hohenstaufen to submit to the emperor. In June, Bernard was back in Italy, taking a leading part in the pro-Innocent council of Pisa, which excommunicated Anacletus. In northern Italy, Bernard then persuaded the Lombard rulers of Milan, normally key opponents of imperial claims to sub to Lothair and Innocent. The Milanese leaders even reportedly attempted to coerce Bernard against his will into becoming bishop of Milan, which he refused to do.

Anacletus, however, was not so easily dislodged. Despite Bernard’s best efforts, Christendom continued to live as a Body of Christ with two heads. In 1137, the year of Emperor Lothair's last journey to Rome, Bernard again came to Italy, where, at Salerno, he attempted by failed to induce Roger of Sicily to declare against Anacletus. In Rome itself, however, he had more success in agitating against the “anti-pope.”

When Anacletus finally died on January 25, 1138, Cardinal Gregorio Conti was elected his successor, assuming the name of Victor IV. Bernard's crowning achievement in the long contest was the abdication of the new “antipope,” the result of Bernard's personal influence. The schism of the Church was healed and the abbot of Clairvaux was free to return in triumph to his monastery.

The contest with Abelard

Clairvaux itself had meanwhile (1135–1136) been transformed outwardly—notwithstanding the reported reluctance of Bernard—into a more suitable seat for an influence that overshadowed that of Rome itself. Despite an outward posture of humility, Bernard was soon once again passionately involved in a major controversy, this time not over Church politics, but theology. His nemesis this time was the greatest intellect of the age, Peter Abelard.

Considering the attitude typified by Abelard to represent a serious threat to the spiritual foundations of Christendom, Bernard accused the brilliant scholar of heresy and became his prosecutor in his trial. He brought a total of 14 charges against Abelard, concerning the nature of the Trinity and God's mercy. Bernard had long been hostile to the scholars at the University of Paris, the center of the new scholastic learning based on Aristotilean principles. He accused those who learned "merely in order that they might know" of being spiritually arrogant and unduly proud of their learned reputations. For Bernard, the liberal arts should serve to prepare a man for the priesthood, not an abstract search for truth in itself.

When, however, Bernard had opened the caseat Sens in 1141, Abélard appealed to Rome. Bernard nevetheless succeeding in getting a condemnation passed at the council, although it was non-binding outside of it local jurisdiction. He did not rest a moment until a second condemnation was procured at Rome in the following year. Abelard, meanwhile, had collapsed at the abbey of Cluny on his way to defend himself at Rome. He lingered there only a few months before dying. How the age's most gifted spiritual leader might have fared in a direct confrontation with the age's greatest intellect therefore remains a question of discussion.

Bernard and the Cistercian Order

One result of Bernard's fame was the growth of the Cistercian order. Between 1130 and 1145, no less than 93 monasteries in connection with Clairvaux were either founded or affiliated from other rules, three being established in England and one in Ireland. In 1145, a Cistercian monk, once a member of the community of Clairvaux—another Bernard, abbot of Aquae Silviae near Rome—was elected as Pope Eugenius III. This was a triumph for the order; as well as for Bernard, who complained that all who had suits to press at Rome applied to him, as though he himself had become pope.

Bernard and heresy

Having previously healed the schism within the church, Bernard was now called upon to combat heresy. Languedoc especially had become a hotbed of heresy and at this time the preaching of Henry of Lausanne was drawing thousands from the orthodox faith. In June 1145, at the invitation of Cardinal Alberic of Ostia, Bernard traveled in the south. There his preaching and reputation, aided by his emaciated ascetic's looks and simple attire, was an effective tool for the Catholic cause at least temporarily, since it provided evidence that the Cathars and Waldensians did not possess a monopoly on missionary work and humility.

The Second Crusade

Even more important was his activity in the following year, when Bernard was asked by Louis VII whether it would be right to raise a crusade (Odo of Deuil, De Profectione). Bernard reserved judgment until Pope Eugene III soon commanded him to preach the Second Crusade. The effect of his eloquence was extraordinary. At the great meeting at Vézelay, on March 21, after Bernard's sermon, King Louis VII of France and his queen, Eleanor, took the cross, together with a host of all classes, so numerous that the stock of crosses was soon exhausted.—Bernard had previously been instrumental in holding together the couple’s marriage, but it is likely that Louis and Eleanor had decided to take the cross prior to hearing Bernard preach. Nevertheless, the effect of their formally responding to his call had a tremendous effect.—

Bernard continued through northern France, and also preached in Flanders and the Rhine provinces. One reason for his extended preaching tour into Germany was the rabble-rousing of an itinerant monk, Radulf, who had stirred the German populace to violent anti-Semitic attacks. Bernard persuaded the populace not to murder the Jews of Europe but to “scatter” them instead. At Speyer on Christmas Day he also succeeded in persuading Conrad, king of the Romans, to join the crusade.

The news of the defeats of the crusading host first reached Bernard at Clairvaux, where Pope Eugene III, driven from Rome by the revolution of Arnold of Brescia, was his guest. Bernard had in March and April 1148 accompanied the pope to the council of Reims, where he led the attack on certain propositions of the scholastic theologian Gilbert de la Porrée. Bernard's influence, previously a decisive threat to those whom he challenged on theological grounds, on this occasion had little effect, perhaps a result of the news that the war he helped to initiate had proven a failure. The disastrous outcome of the Crusade was a blow to Bernard, who found it difficult to understand why God would move in this way. Declining to believe that he and the pope could have been wrong to support the Crusade in the first place, he ascribed it to the sins of the crusaders (Episte 288; de Consideratione. ii. I).

On the news of the disaster that had overtaken the crusaders, an effort was made to salvage the effort by organizing another expedition. At the invitation of Suger, abbot of St Denis, now the virtual ruler of France, Bernard attended a meeting at Chartres in 1150 convened for this purpose. Here, he himself was elected to conduct the new crusade. Eugenius III, however, held back from fully endorsing this project, and Bernard eventually wrote to pope claiming that intended to lead such a crusade. Bernard was aging, exhausted by his austerities , and saddened by the failure of the Second Crusade as well as by loss of several of his early friends. His zeal to involve himself in the great affairs of the Church, however remained undimmed. His last work, the De Consideratione, written to Eugene III and describing the nature of papal power, shows no sign of failing power.

Bernard and the veneration of the Virgin Mary

Bernard expanded upon Anselm of Canterbury's role in transmuting the sacramentally ritual Christianity of the Early Middle Ages into a new, more personally held faith, with the life of Christ as a model and a new emphasis on the Virgin Mary. In opposition to the rational approach to divine understanding adopted by the scholastics, Bernard preached an immediate and personal faith, in which the intercessor was the Mary—"the Virgin that is the royal way, by which the Saviour comes to us." Prior to this time Mary had played a relative minor role in popular piety in Europe, and Bernard was the single most important force in championing her cause. [1]

Bernard's character

The greatness of Bernard is generally regarded as being his character. The age saw him as the embodiment of its ideal: that of medieval monasticism at its highest development in contrast to the corruption and wealth of the Roman clergy. The world’s riches had no meaning for Bernard, as the world itself was merely a place of temporary banishment and trial, in which men are but "strangers and pilgrims" (Serm. i., Epiph. n. I; Serm. vii., Lent. n. I). For him, the truth was already known and the way of grace was clear. The function of theology, therefore, was merely to maintain the landmarks inherited from divinely inspired Church tradition. He had no sympathy with the dialectics of scholastic teachers, who he generally considered to be leading people astray from grace. With merciless logic, he followed the principles of the Christian faith as he conceived it.

As for heretics, he preferred that they should be vanquished “not by force of arms, but by force of argument." However, if a heretic refused to see the error of his ways, Bernard considered that " he should be driven away, or even a restraint put upon his liberty" (Serm. lxiv). He was troubled by the mob violence that made the heretics "martyrs to their unbelief." However, he added that, "it would without doubt be better that they should be coerced by the sword than that they should be allowed to draw away many other persons into their error." (Serm. lxvi. on Canticles ii. 15).

Bernard at his best displays a nobility of nature, a wise charity and tenderness in his dealings with others, and a genuine humility, making him one of the most complete exponents of the Christian life. His broad Christian character is witnessed to by the enduring quality of his influence. His works have been reprinted in many editions. This is perhaps due to the fact that the chief fountain of his own inspiration was the Bible itself, as well as to his spirit of humility that rejected the opulence of medieval Catholicism, giving his authority a quality that survived that Reformation.

In The Divine Comedy, Bernard is the last of Dante's spiritual guides and offers his prayer to the Virgin Mary to grant Dante the vision of the true nature of God, which is the climax of the story.

"Bernard," wrote Erasmus of Rotterdam in his Art of Preaching, "is an eloquent preacher, much more by nature than by art; he is full of charm and vivacity and knows how to reach and move the affections." The same is true of the letters and to an even more striking degree. They are written on a variety of subjects, great and small, to people of the most diverse stations and types; and they help us to understand the adaptable nature of the man, which enabled him to appeal as successfully to the uneducated as to the learned.

Modern relevance of Bernard's writings

In August 2006, speaking during a Sunday address at the summer papal palace in Castel Gandolfo, Pope Benedict XVI quoted from one of the writings of Bernard, his Five Books on Consideration: Advice to a Pope (De Consideratione), Bernard's last work, written about 1148 at the pope's request for the edification and guidance of Eugenius III.

Benedict quoted Bernard as advising pontiffs to "watch out for the dangers of an excessive activity, whatever... the job that you hold, because many jobs often lead to the 'hardening of the heart,' as well as 'suffering of the spirit, loss of intelligence."

Works

Bernard's works fall into three categories:

- (1) Letters, of which over five hundred have been preserved, of great interest and value for the history of the period and as an insight into his character.

- (2) Treatises:

- (a) dogmatic and polemical, De gratia et libero arbitrio, written about 1127, and following closely the lines laid down by St Augustine of Hippo; De baptismo aliisque quaestionibus ad mag. Ilugonem de S. Victore; Contra quaedam capitala errorum Abaelardi ad Innocentem II (in justification of the action of the synod of Sens);

- (b) ascetic and mystical, De gradibus humilitatis ci superbiae, his first work, written perhaps about 1121; De diligendo Deo (about 1126); De conversione ad clericos, an address to candidates for the priesthood; De Consideratione, Bernard's last work, written about 1148 at the pope's request for the edification and guidance of Eugene III;

- (c) about monasticism, Apologia ad Guilelmum, written about 1127 to William, abbot of St Thierry; De laude novae militiae ad milites templi (c. 1132—1136); De precepto et dispensatione, an answer to various questions on monastic conduct and discipline addressed to him by the monks of St Peter at Chartres (some time before 1143);

- (d) on ecclesiastical government, De moribus et officio episcoporum, written about 1126 for Henry, bishop of Sens; the De Consideratione mentioned above;

- (e) a biography, De vita et rebus gestis S. Maiachiae, Hiberniae episcopi, written at the request of the Irish abbot Congan and with the aid of materials supplied by him; it is of importance for the ecclesiastical history of Ireland in the 12th century;

- (f) sermons—divided into Sermones de tempore; de sanctis; de diversis; and eighty-six sermons, in Cantica Canticorum, an allegorical and mystical exposition of the Song of Solomon;

- (g) hymns. Many hymns ascribed to Bernard survive, e.g. Jesu dulcis memoria, Jesus rex admirabilis, Jesu decus angelicum, Salve Caput cruentatum.

Of these the three first are included in the Roman breviary. Many have been translated and are used in Protestant churches.

Editions

The first time Bernard's works were published in anything like a complete edition was in 1508 at Paris, under the title Seraphica melliflui devotique doctoris S. Bernardi scripta, edited by André Bocard. The first really critical and complete edition is that of Dom J. Mabillon, Sancti Bernardi opp. etc. (Paris, 1667, improved and enlarged in 1690, then again by René Massuet and Texier in 1719), reprinted by JP Migne, Patrolog. lat. (Paris, 1859).

The modern critical edition is edited by Leclerq, Talbot and Rochais (8 vols., Rome, 1958-1975). There is an English translation of Mabillon's edition, which includes, however, only the letters and the sermons on the Song of Songs, with the biographical and other prefaces, by Samuel J. Eales (4 vols., London, 1889—1895). More recent (1970s-1990s) English translations of many of Bernard's works can be found in the Cistercian Fathers series, published by Cistercian Publications.[2]

Prayer To The Shoulder Wound Of Christ

It is related in the annals of Clairvaux, that St. Bernard asked Our Lord which was His greatest unrecorded suffering and Our Lord answered, "I had on My Shoulder, while I bore My Cross on the Way of Sorrows, a grievious Wound which was more painful than the others and which is not recorded by men. Honor this Wound with thy devotion and I will grant thee whatsoever thou dost ask through its virtue and merit and in regard to all those who shall venerate this Wound, I will remit to them all their venial sins and will no longer remember their mortal sins."

"O Loving Jesus, Meek Lamb of God, I miserable sinner, salute and worship the most Sacred Wound of Thy Shoulder on which Thou didst bear Thy heavy Cross, which so tore Thy Flesh and laid bare Thy Bones as to inflict on Thee an anguish greater than any other wound of Thy Most Blessed Body. I adore Thee, O Jesus most sorrowful; I praise and glorify Thee and give Thee thanks for this most sacred and painful Wound, beseeching Thee by that exceeding pain and by the crushing burden of Thy heavy Cross, to be merciful to me, a sinner, to forgive me all my mortal and venial sins and to lead me on towards Heaven along the Way of Thy Cross. Amen."

Notes

- ↑ Cantor 1993 p. 341

- ↑ http://www.cistercianpublications.org

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Cantor, Norman F. 1993. The Civilization of the Middle Ages

- This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

See also

- Clairvaux Abbey

- Christian mystics

External links

- Opera omnia Sancti Bernardi Claraevallensis (The Complete Works of St. Bernard of Clairvaux, in Latin)

- New Advent Catholic Encyclopedia: St. Bernard of Clairvaux

- in progress: critical edition, french translation with notes of the complete works of Bernard of Clairvaux ; indexes on line : [1]Institut des Sources Chrétiennes

- Adrian Fletcher’s Paradoxplace - Saint Bernard and the Cistercians plus Abbey Photos

- Saint Bernard of Clairvaux A slightly less adulatory assessment

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.