Zulu

| Zulus | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

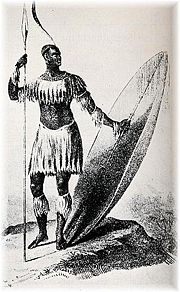

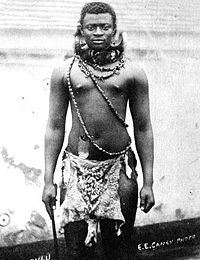

| Zulu warriors, late nineteenth century (Europeans in background) | ||||||||||||

| Total population | ||||||||||||

| 10,659,309 (2001 census)[1] | ||||||||||||

| Regions with significant populations | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

| Languages | ||||||||||||

| Zulu (many also speak English or Afrikaans or Portuguese or other indigenous languages such as Xhosa) | ||||||||||||

| Religions | ||||||||||||

| Christian, African Traditional Religion | ||||||||||||

| Related ethnic groups | ||||||||||||

| Bantu · Nguni · Basotho · Xhosa · Swazi · Matabele · Khoisan |

The Zulu are a South African ethnic group of an estimated 17-22 million people who live mainly in the province of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. They form South Africa's largest single ethnic group. Small numbers also live in Zimbabwe, Zambia, and Mozambique. Their language, isiZulu, is a Bantu language; more specifically, part of the Nguni subgroup. Under their leader Shaka the Zulu kingdom was formed in the early nineteenth century.

A patriarchal society, the gender roles of Zulu are clearly delineated, with the boys and men organized as warriors in support of the king. The Zulu Kingdom played a major role in South African History during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Under apartheid, Zulu people were classed as third-class citizens and suffered from state sanctioned discrimination. Today, they are the most numerous ethnic group in South Africa, and have equal rights along with all other citizens. They continue to be proud of their culture, and are famous for their beadwork, which is not only beautiful but traditionally the patterns were used for communication, and their music has become popular worldwide. Thus, despite a history of struggle, conflict, and oppression, the Zulu people are finding their place in contemporary society.

Language

The language of the Zulu people is Zulu or isiZulu, a Bantu language; more specifically, part of the Nguni subgroup. Zulu is the most widely spoken language in South Africa, with more than half of the South African population able to understand it. Many Zulu people also speak English, Portuguese, Shangaan, Sesotho and others from among South Africa's eleven official languages.

History

The Zulu were originally a minor clan in what is today Northern KwaZulu-Natal, founded ca. 1709 by Zulu kaNtombhela. In the Zulu language, Zulu means "heaven," or "sky." At that time, the area was occupied by many large Nguni tribes and clans. Nguni tribes had migrated down Africa's east coast over thousands of years, probably arriving in what is now South Africa in about the year 800 C.E.

The rise of the Zulu kingdom under Shaka

Shaka Zulu was the illegitimate son of Senzangakona, chief of the Zulus. He was born circa 1787. He and his mother, Nandi, were exiled by Senzangakona, and found refuge in the Mthethwa. Shaka fought as a warrior under Dingiswayo, chief of the Mthethwa. When Senzangakona died, Dingiswayo helped Shaka claim his place as chief of the Zulu Kingdom.

Shaka was succeeded by Dingane, his half brother, who conspired with Mhlangana, another half-brother, to murder him. Following this assassination, Dingane murdered Mhlangana, and took over the throne. One of his first royal acts was to execute all of his royal kin. In the years that followed, he also executed many past supporters of Shaka in order to secure his position. One exception to these purges was Mpande, another half-brother, who was considered too weak to be a threat at the time.

In October, 1837, the Voortrekker leader Piet Retief visited Dingane at his royal kraal to negotiate a land deal for the Voortrekkers. In November, about 1,000 Voortrekker wagons began descending the Drakensberg mountains from the Orange Free State into what is now KwaZulu-Natal.

Dingane asked that Retief and his party retrieve some cattle stolen from him by a local chief. This Retief and his men did, returning on February 3, 1838. The next day, a treaty was signed, wherein Dingane ceded all the land south of the Tugela River to the Mzimvubu River to the Voortrekkers. Celebrations followed. On February 6, at the end of the celebrations, Retief's party were invited to a dance, and asked to leave their weapons behind. At the peak of the dance, Dingane leapt to his feet and yelled Bambani abathakathi! (isiZulu for "Seize the wizards"). Retief and his men were overpowered, taken to the nearby hill kwaMatiwane, and executed. Some believe that they were killed for withholding some of the cattle they recovered, but it is likely that the deal was a ploy to overpower the Voortrekkers. Dingane's army then attacked and massacred a group of 500 Voortrekker men, women and children camped nearby. The site of this massacre is today called Weenen (Dutch for "to weep").

The remaining Voortrekkers elected a new leader, Andries Pretorius, and Dingane suffered a crushing defeat at the Battle of Blood River on December 16, 1838, when he attacked a group of 470 Voortrekker settlers led by Pretorius. Following his defeat, Dingane burned his royal household and fled north. Mpande, the half-brother who had been spared from Dingane's purges, defected with 17,000 followers, and, together with Pretorius and the Voortrekkers, went to war with Dingane. Dingane was assassinated near the modern Swaziland border. Mpande then took over rulership of the Zulu nation.

Following the campaign against Dingane, in 1839 the Voortrekkers, under Pretorius, formed the Boer republic of Natalia, south of the Thukela, and west of the British settlement of Port Natal (now Durban). Mpande and Pretorius maintained peaceful relations. However, in 1842, war broke out between the British and the Boers, resulting in the British annexation of Natalia. Mpande shifted his allegiance to the British, and remained on good terms with them.

In 1843, Mpande ordered a purge of perceived dissidents within his kingdom. This resulted in numerous deaths, and the fleeing of thousands of refugees into neighboring areas (including the British-controlled Natal). Many of these refugees fled with cattle. Mpande began raiding the surrounding areas, culminating in the invasion of Swaziland in 1852. However, the British pressured him into withdrawing, which he did shortly.

At this time, a battle for the succession broke out between two of Mpande's sons, Cetshwayo and Mbuyazi. This culminated in 1856 with a battle that left Mbuyazi dead. Cetshwayo then set about usurping his father's authority. In 1872, Mpande died of old age, and Cetshwayo took over rulership.

Anglo-Zulu War

On December 11, 1878, agents of the British delivered an ultimatum to 14 chiefs representing Cetshwayo. The terms of the ultimatum were unacceptable to Cetshwayo. British forces crossed the Thukela river at the end of December 1878. The war took place in 1879. Early in the war, the Zulus defeated the British at the Battle of Isandlwana on January 22, but were severely defeated later that day at Rorke's Drift. The war ended in Zulu defeat at the Battle of Ulundi on July 4.

Cetshwayo was captured a month after his defeat, and then exiled to Cape Town. The British passed rule of the Zulu kingdom onto 13 "kinglets," each with his own subkingdom. Conflict soon erupted between these subkingdoms, and in 1882, Cetshwayo was allowed to visit England. He had audiences with Queen Victoria, and other famous personages, before being allowed to return to Zululand, to be reinstated as king.

In 1883, Cetshwayo was put in place as king over a buffer reserve territory, much reduced from his original kingdom. Later that year, however, Cetshwayo was attacked at Ulundi by Zibhebhu, one of the 13 kinglets, supported by Boer mercenaries. Cetshwayo was wounded and fled. Cetshwayo died in February 1884, possibly poisoned. His son, Dinuzulu, then 15, inherited the throne.

In order to fight back against Zibhebhu, Dinuzulu recruited Boer mercenaries of his own, promising them land in return for their aid. These mercenaries called themselves "Dinuzulu's Volunteers," and were led by Louis Botha. Dinuzulu's Volunteers defeated Zibhebhu in 1884, and duly demanded their land. They were granted about half of Zululand individually as farms, and formed an independent republic. This alarmed the British, who then annexed Zululand in 1887. Dinuzulu became involved in later conflicts with rivals. In 1906 Dinuzulu was accused of being behind the Bambatha Rebellion. He was arrested and put on trial by the British for "high treason and public violence." In 1909, he was sentenced to ten years' imprisonment on Saint Helena island. When the Union of South Africa was formed, Louis Botha became its first prime minister, and he arranged for his old ally Dinuzulu to live in exile on a farm in the Transvaal, where Dinuzulu died in 1913.

Dinuzulu's son Solomon kaDinuzulu was never recognized by South African authorities as the Zulu king, only as a local chief, but he was increasingly regarded as king by chiefs, by political intellectuals such as John Langalibalele Dube and by ordinary Zulu people. In 1923, Solomon founded the organization Inkatha YaKwaZulu to promote his royal claims, which became moribund and then was revived in the 1970s by Mangosuthu Buthelezi, chief minister of the KwaZulu bantustan. In December 1951, Solomon's son Cyprian Bhekuzulu kaSolomon was officially recognized as the Paramount Chief of the Zulu people, but real power over ordinary Zulu people lay with white South African officials working through local chiefs who could be removed from office for failure to cooperate.

Apartheid years

Under apartheid, the homeland of KwaZulu (Kwa meaning place of) was created for Zulu people. In 1970, the Bantu Homeland Citizenship Act provided that all Zulus would become citizens of KwaZulu, losing their South African citizenship. KwaZulu consisted of a large number of disconnected pieces of land, in what is now KwaZulu-Natal. Hundreds of thousands of Zulu people living on privately owned "black spots" outside of KwaZulu were dispossessed and forcibly moved to bantustans - worse land previously reserved for whites contiguous to existing areas of KwaZulu - in the name of "consolidation." By 1993, approximately 5.2 million Zulu people lived in KwaZulu, and approximately 2 million lived in the rest of South Africa. The Chief Minister of KwaZulu, from its creation in 1970 (as Zululand) was Chief Mangosuthu Buthelezi. In 1994, KwaZulu was joined with the province of Natal, to form modern KwaZulu-Natal.

In 1975, Buthelezi revived the Inkatha YaKwaZulu, predecessor of the Inkatha Freedom Party. This organization was nominally a protest movement against apartheid, but held more conservative views than the ANC. For example, Inkatha was opposed to the armed struggle, and to sanctions against South Africa. Inkatha was initially on good terms with the ANC, but the two organizations came into increasing conflict beginning in 1979 in the aftermath of the Soweto Uprising.

Because its stances were more in accordance with the apartheid government's views, Inkatha was the only mass organization recognized as being representative of the views of black South Africans by the apartheid government (the ANC and other movements were banned). In the last years of apartheid, this acceptance extended to the covert provision of funds and guerrilla warfare training to Inkatha by the government. Yet unlike the leaders of the Transkei, Ciskei, Bophuthatswana and Venda bantustans, Buthelezi never accepted the pseudo-independence offered under the policy of Separate Development, despite strong pressure from the ruling white government.

From 1985, members of opposing protest movements in what is now KwaZulu-Natal began engaging in bloody armed clashes. This political violence occurred primarily between Inkatha and ANC members, and included atrocities committed by both sides. The violence continued through the 1980s, and escalated in the 1990s in the build up to the first national elections in 1994.

Culture

Zulu women take pride in caring for children and the elderly. A childless woman is frowned upon, and often loses any sort of status associated with being a wife. The elderly are never shipped off to old age homes. It is considered highly unnatural and improper, and the duty of their caretaking falls upon the daughters-in-law and grandchildren. Cleaning the home is also a natural occupation of Zulu women, some using modern conveniences and sophisticated machinery, others using the more traditional cow dung to polish floors. Zulus learn from an early age that the womenfolk are meant to do all of the cooking at mealtimes, and a Zulu man would often rather go hungry than cook for himself. Contemporary Zulus enjoy their meals at a table, whereas the traditional Zulus eat over grass mats on the floor.

Religion

Zulu people can be Christians (whether Roman Catholics or Protestants in Mozambique, South Africa, and Zimbabwe, or part-Christian, part-Traditionalist in Zimbabwe) or pure Traditionalist.

Zulu traditional mythology contains numerous deities, commonly associated with animals or general classes of natural phenomena.

Unkulunkulu (Nkulunkulu) is the highest God and is the creator of humanity. Unkulunkulu ("the greatest one") was created in Uhlanga, a huge swamp of reeds, before he came to Earth. Unkulunkulu is sometimes conflated with the Sky Father Umvelinqangi (meaning "He who was in the very beginning"), god of thunder and earthquakes. Another name given for the supreme being is uThixo.

Unkulunkulu is above interacting in day-to-day human affairs. It is possible to appeal to the spirit world only by invoking the ancestors (amaDlozi) through divination processes. As such, the diviner, who is almost always a woman, plays an important part in the daily lives of the Zulu people. It is believed that all bad things, including death, are the result of evil sorcery or offended spirits. No misfortune is ever seen as the result of natural causes.

Other deities include Mamlambo, the goddess of rivers, and Nokhubulwane, sometimes called the Zulu Demeter, who is a goddess of the rainbow, agriculture, rain and beer (which she invented).

Uhlakanyana is an evil dwarf-like being; Intulo is a lizard. Unwabu is a chameleon who was sent to humanity to grant them immortality. Unwabu was too slow, leading to the current mortality of humanity. The chameleon's color changes from green to brown because it is mourning Unwabu's sloth.

One of the most visible signs of Zulu mythology in South Africa is the fact that most people, even in urban areas, will sleep with their beds raised on bricks in order to avoid the Tokoloshe. The Tokoloshe is a small mischievous creature that fights people, usually killing them; if he loses, he will teach the human magic and healing.

Another important aspect of Zulu religion is cleanliness. Separate utensils and plates were used for different foods, and bathing often occurred up to three times a day. Going barefoot has always been a traditional sign of Zulu spirituality and strength. Christianity had difficulty gaining a foothold among the Zulu people, and when it did it was in a syncretic fashion. Isaiah Shembe, considered the Zulu Messiah, presented a form of Christianity (the Nazareth Baptist Church) which incorporated traditional customs.[6]

Zulu beadwork

The KwaZulu/Natal province of South Africa is internationally renowned for its colorful Zulu beadwork. Traditional color combinations and patterns can still be found, but modern Zulu beadwork is evolving towards more contemporary styles. More than simply decorative weavings of intricate bead patterns, the beadwork has often been used as a means of communication between genders, conveying messages of both courtship and warnings.

The visual art of this feminine craft relates directly in one way or another to attracting a mate and marriage. Males are the traditional clients and purchasers and receivers of these beadworks, and they wear them to show involvement with women whom they are courting.

The geometric figures incorporate color-coded symbols which portray certain values. The three ways of determining a design are through the combination and arrangement of colors, the use and nature of an object, and the deliberate breaking of rules which guide these factors. The Zulu beadwork serves as both a social function, and also has political connotations, proudly displaying certain regional colors.

Zulu music

The singing styles of the Zulu people are worthy of special mention. As in much of Africa, music is highly regarded, enabling the communication of emotions and situations which could not be explained by talking. Zulu music incorporates rhythm, melody, and harmony — the latter is usually dominant and known as "isigubudu" (which can be translated as converging horns on a beast, with tips touching the animal, a spiraling inward that reflects inner feelings).

Zulu music has also been carried worldwide, often by white musicians using Zulu backing singers, or performing songs by Zulu composers. A famous example of the former is Paul Simon. Examples of the latter are the song "Wimoweh" which was used in the Disney animated film The Lion King; the Zulu language is also sung in the opening song of the film, Circle of Life.

Isicathamiya

Isicathamiya (with the 'c' pronounced as a dental click) is an a cappella singing style that originated from the South African Zulus. The word itself does not have a literal translation; it is derived from the Zulu verb -cathama, which means "walking softly," or "tread carefully." Isicathamiya contrasts with an earlier name for Zulu a cappella singing, mbube, meaning "lion." The change in name marks a transition in the style of the music: traditionally, music described as Mbube is sung loudly and powerfully, while isicathamiya focuses more on achieving a harmonious blend between the voices. The name also refers to the style's tightly-choreographed dance moves that keep the singers on their toes.

Isicathamiya choirs are traditionally all male. Its roots reach back before the turn of the twentieth century, when numerous men left the homelands in order to search for work in the cities. As many of the tribesmen became urbanized, the style was forgotten through much of the twentieth century. Today, isicathamiya competitions take place in Johannesburg and Durban, with up to 30 choirs performing.

Mbube

Mbube is a form of South African vocal music. The word mbube means "lion." Traditionally performed a cappella, the style is sung in a powerful and loud way. The members of the group are usually male, although quite a few groups often have a female singer. The style itself dates, to the times when young Zulu men left their families to travel to the major cities to find work — often in mines. In order to preserve a sense of community, these young men would form choirs and perform Mbube music.

Contemporary Zulu

The modern Zulu population is fairly evenly distributed in both urban and rural areas. Although KwaZulu-Natal is still their heartland, large numbers have been attracted to the relative economic prosperity of Gauteng province.

Zulus play an important part in South African politics. Mangosuthu Buthelezi served a term as one of two Deputy Presidents in the government of national unity which came into power in 1994, when reduction of civil conflict between ANC and IFP followers was a key national issue. Within the ANC, both the Zulus have served as Deputy President, in part to bolster the ANC's claim to be a pan-ethnic national party and refute IFP claims that it was primarily a Xhosa party.

Notes

- ↑ 2001 Census. South Africa grows to 44.8 million, on the site southafrica.info published for the International Marketing Council of South Africa, dated 9 July 2003, retrieved 4 March 2005.

- ↑ 2001 Census

- ↑ 2001 Census

- ↑ 2001 Census

- ↑ 2001 Census

- ↑ [1] Art & Life in Africa Online - Zulu University of Iowa. accessdate 2007-06-06

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Hall, Sheldon. Zulu: With Some Guts Behind It. Tomahawk Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0953192663

- Laband, John. Kingdom in Crisis: The Zulu Response to the British - Invasion of 1879. Barnsley, South Yorkshire, UK: Pen and Sword Books, 2007. ISBN 978-1844155842

- Morris, Jean and Eleanor Preston-Whyte, Speaking With Beads: Zulu Arts from Southern Africa. London: Thames & Hudson, 1994. ISBN 978-0500277577

- Musgrove, Margaret and Diane Dylan. Ashanti to Zulu: African Traditions. London: Puffin, 1992. ISBN 978-0140546040

- Veit, Erlmann. Nightsong: Power, Performance, and Practice in South Africa. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1995. ISBN 978-0226217215

External links

All links retrieved June 13, 2023.

- Zulu People of Africa.

- Human Rights Watch report on KwaZulu, just prior to the 1994 elections. - This includes detailed, well-referenced sections on recent Zulu history.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.